The so-called neo-progressive bands were a competitive bunch, with IQ, Pendragon, Pallas, Marillion and their ilk all fiercely competing to establish themselves as the leaders of the movement. By June of 1985, Marillion had an unpredictable, breakthrough success with Kayleigh and Misplaced Childhood and although commercial acclaim may have overlooked IQ, they released a similarly iconic album in The Wake that summer which is rightly regarded as one of the genuine highlights of early 80s prog. The album was IQ’s second full-length release (third if you include 1982’s tape-only Seven Stories Into Eight) and captured the band trying to produce a professional and cohesive release to match that of their contemporaries and outshine their low-budget earlier albums.

“All of those bands were seriously competitive,” recalls singer Peter Nicholls. “With progressive music being such a clique area, everybody was vying for the limited success there was to be had. The rivalry wasn’t exactly vicious but we were determined to make our second album a more polished affair and something which was a clear indication of what we felt we were capable of. What is often forgotten is that we really were doing ourselves no favours at all by choosing to play progressive music and we knew that by pursuing that avenue, the chances of any mainstream success were very remote.

"At the time, the popular music was very slick, polished and professional, and even bands like Yes pursued that avenue with their 90125 album. We were always fighting against a perception that to play progressive music you had to adopt a very retrospective, 1970s prog rock lifestyle. Of course we loved that music but we also loved Human League and The Psychedelic Furs, and we always tried to drag those influences in. We were never about slavishly recreating what had gone before and by the time of The Wake we really started to sound like IQ. We knew what we were doing was really unfashionable but we thought ‘Well, if it’s not in fashion, then it can’t go out of fashion’.”

Yet the writing of the album was to prove exceptionally demanding for IQ, and the period was unquestionably the darkest in their history. The pressures were centred on their decision to live together in a single flat, which, although meaning they were able to concentrate on musical creation, also resulted in an unhealthy and claustrophobic atmosphere which was exacerbated by a lack of money and the squalor of the flat.

“At the time, most of us were living in a communal house in Harlesden, which was every bit as chaotic and unhygienic as the one inhabited by The Young Ones in the TV series,” explains IQ’s then keyboard player Martin Orford. “I have vivid recollections of mould in the bedrooms, a dead mouse in the toaster, a tape machine which cut out every time the fridge came on and lots and lots of arguing.”

“The problem was that minor disagreements became exaggerated and everything was under the microscope because we could never get away from each other,” adds Nicholls. “We could never really crank up the music because we had a neighbour in the upstairs flat, Nancy, who used to scrutinise us like a hawk. After gigs, we would all be walking on tiptoes at three in the morning trying to get all the instruments back into the flat without being discovered. I have a lot of fond memories but at the time it was very arduous and we survived on next-to-nothing in terms of food. I think we each spent about two pounds a week on bread and beans.”

In spite of such turbulence, the band had spent months piecing together the tracks which would ultimately form The Wake. Orford and Holmes crafted tracks such as the brooding Corners and Headlong during regular escapes from London to their hometown of Southampton. Widow’s Peak which would become a cornerstone of their live set, had already been recorded for a session on BBC Radio One’s Friday Rock Show and a session in Glasgow also yielded rough demos of The Thousand Days and The Magic Roundabout – the latter named because a section of it reminded bassist Tim Esau of the theme tune to the children’s TV programme of the same name.

“Yes, I admit responsibility for that one but I think I did vote against keeping it as a title,” says Esau. “As a punishment from that day forth, while Mike was giving it everything on his guitar at that point in the live set, I was thinking of Zebedee, Florence and Dougal and singing The Magic Roundabout theme in my head.”

The band’s domestic cabin fever was partially alleviated when Peter Nicholls moved back to his home town of Manchester from London in early 1985. Yet although that might have solved one predicament, it led to the singer feeling increasingly remote from the band during the writing of The Wake and was the origin of a rift within IQ that would ultimately cause the singer the quit the band later that year.

“We knew we had to have personal lives. So that was vital and without that, I honestly think the band would have folded around that time,” recalls Nicholls. “To this day I don’t really know what the score was, but there was certainly a distance that grew between the rest of the band and me. There wasn’t a huge argument or one particular moment, but I think we were all kind of spreading our wings and there was a division that was growing between us.”

“Peter had moved out of the band’s communal base by then,” confirms Orford.

“I think he was having a few personal problems and though I’m not entirely sure what they were, he was clearly not a happy soul at the time. Plus communal writing was a complete pain in the arse, especially when you’ve got a bunch of highly opinionated people to deal with. There was an incredible tension present in the band during that period and I felt that someone, and it didn’t enormously matter who, had to go. I’d got pretty cheesed off by then with being in London with no money and having to live on a kind of ongoing and constantly replenished vegetarian stew.”

The upside of that seemingly unsurpassable schism was that the gloomy atmosphere and tension that was enveloping the band was captured in both the music and the lyrics, helping to create an emotionally charged and wonderfully dark album.

“Yeah, I think that is a pretty good observation really,” agrees guitarist Mike Holmes. “It was the old adage that out of conflict and frustration often comes something very creative and having people going through bad times usually equals pretty good music. You only have to hear that Phil Collins is going through another divorce and you expect that will create a set of great lyrics. Certainly with The Wake, I think that’s true. What I really like about that album is that it is really heavy with atmosphere and that was undoubtedly influenced by the mood of the band at the time.”

Matching the moodiness of the music was the interlinked lyrical concept of death that Nicholls had conceived and written. Although not a traditional concept album with a single storyline, IQ were determined to record an album with a consistent and central theme that permeated all the songs.

“I had always had a thing about death and that was a theme that was filtering through the lyrics,” explains Nicholls. “There was an Edgar Allan Poe story which was about someone being buried alive [The Premature Burial – Poe Ed] and that really hid itself in my mind somehow. Outer Limits had working title of The Bridge and I had this idea of somebody walking across a bridge. At the end was heaven, but if you fell off the bridge it was hell. It all sounds very simplistic and a bit like sixth form poetry now, but we combined that and it became the story of someone who dies at the end of the first song and then an account of what happens to his soul after that.”

The album was recorded at London’s Falconers Studios in Camden, which in an uncanny visual reminder of the divisions within the band, was split over two levels.

“The actual control room was in the top area of this building in Camden, the recording room was on the floor below and there was no camera to connect us,” recalls Nicholls. “I was on my own in this strange dark room trying to sing in tune. From a singing point of view, because there seemed to be such a lot of tension in the band, it was hard to loosen up and let go and I can hear that when I listen to the album now. But it’s a piece of its time. Occasionally we talk about re-recording it but we never will because what’s the point? Why would you? Every album is only ever as good as you can make it at the time and no piece of work is ever going to be perfect. I remember when it came out we all felt really positive about the album. It has a really strong atmosphere and we were really were going for it on The Wake. It took us from being just one of the progressive bands of the time to being in the top three or four bands.”

Although the album failed to make a commercial breakthrough, it remains a potent high point in IQ’s back catalogue, and as Martin Orford notes, the longevity and bewitching nature of The Wake is particularly notable given the manner in which the album was created.

“I think we got to Number 72 in the national album charts,” says Orford. “Considering we were all on the dole and still living on that terrible stew made from the discarded veg from Portobello market, we were really pretty impressed with that...”

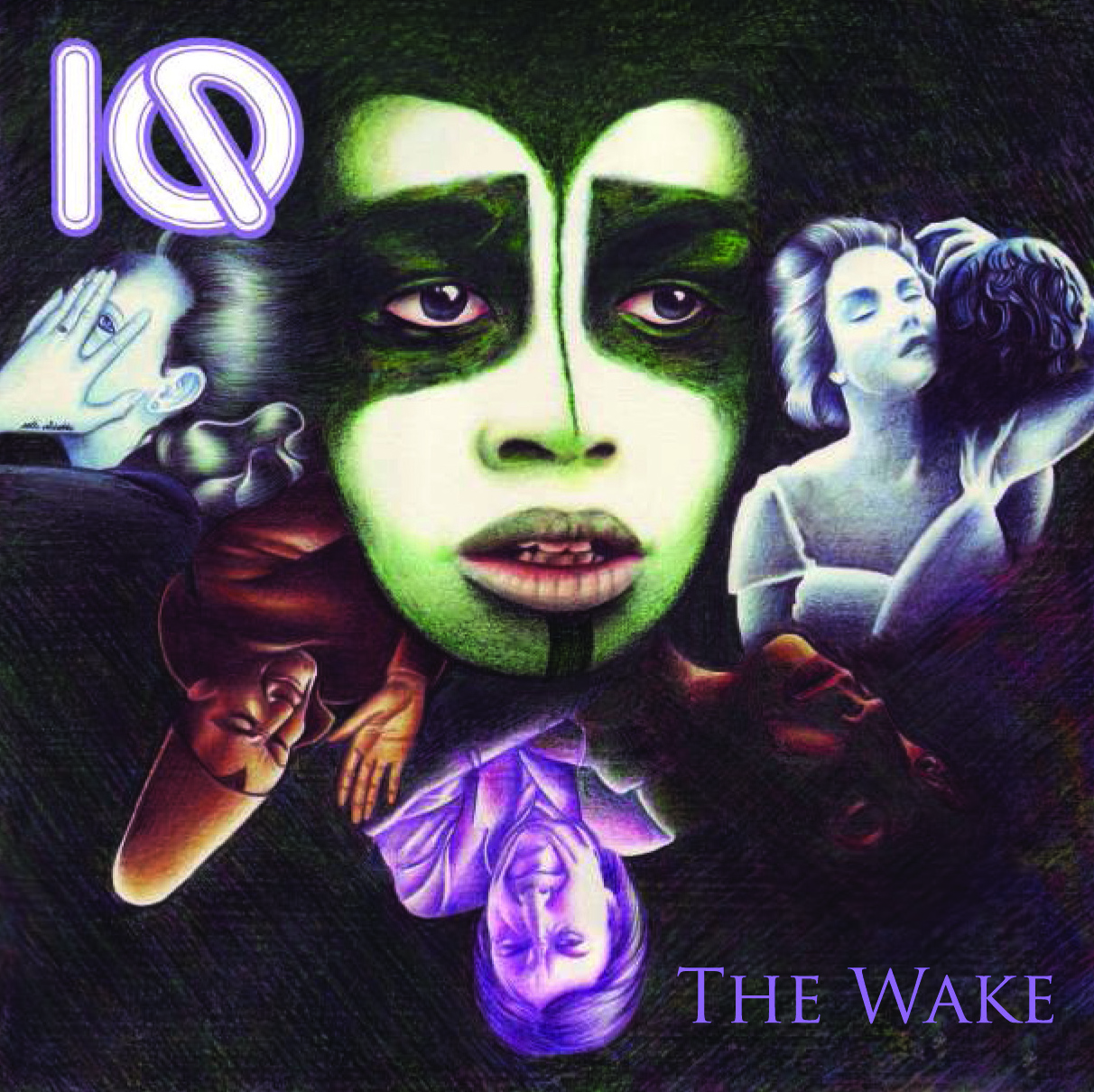

The Story Behind The Album Cover

In-keeping with the chaos surrounding the creation of The Wake, the album’s art also created tension. Depicting a central face with other figures designed around it, the painting had been created by singer Peter Nicholls and unbeknown to him, the other members of the band had mistakenly assumed it was a self-portrait.

“Oh yes, there were problems alright,” reveals Martin Orford. “As far as we were concerned, Pete had stuck a great big picture of himself all over the album cover. He denied it like mad of course, claiming he’d got the idea from some film about primitive jungle tribes, but I’m not sure any of us really believed him. In retrospect did he just unconsciously paint a face that looked like his own without actually realising it? Yeah, maybe he did. It’s an iconic cover anyway so who cares now?”

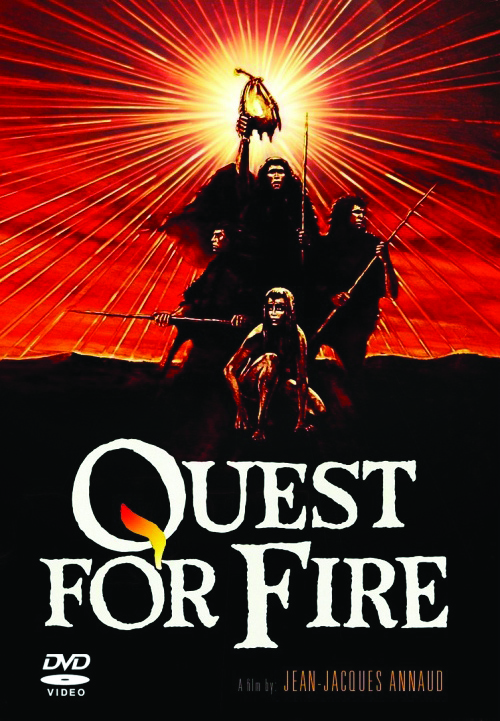

In fact, the image was influenced by a character in the 1981 film, Quest For Fire as Nicholls explains.

“I had absolutely no idea that the band thought that until recently but that was symptomatic of the situation in the band at the time. Maybe on some subliminal level I was attracted to that image because it looked a bit like me, but I don’t know. With the artwork I had the central image and thought I have got to fill the spaces around it, so came up with the other little images. I just filled it up really. To be honest, as it was all done quickly, I imagine there were probably a lot of late nights where I sat there with my pencil crayons trying to get the art finished. But it just illustrates a mood and an atmosphere really. It’s interesting that people saw that face as being me and I suppose that it because of the make up around the eyes. Seriously though, there was no intention there for me to put a picture of me on the cover of an IQ album. Why would I think I could get away with it?”