While the dying embers of the British punk rock scene undoubtedly threw out a spark or three as the 80s began to gain momentum, it was the more daring and inventive ranks of the post-punk and – as it would later be known – alternative rock movements that most credibly carried the spirit of ’76 forward into a shadowy future. Whether embracing the minimalist tendencies of Krautrock or assimilating the sturm und clank of industrial machinery into the punk mix, these were bands that had no interest in repeating the past. And yet, within that supposedly forward-thinking mindset, there lurked a strong strain of conservatism that threatened to squeeze all the rock’n’roll juice out of punk’s DIY ethos. The Cult, arguably the biggest success story of this nebulous subculture’s golden era, changed all that in 1985 when they released their second album, the monumental slab of priapic psychedelia known as Love.

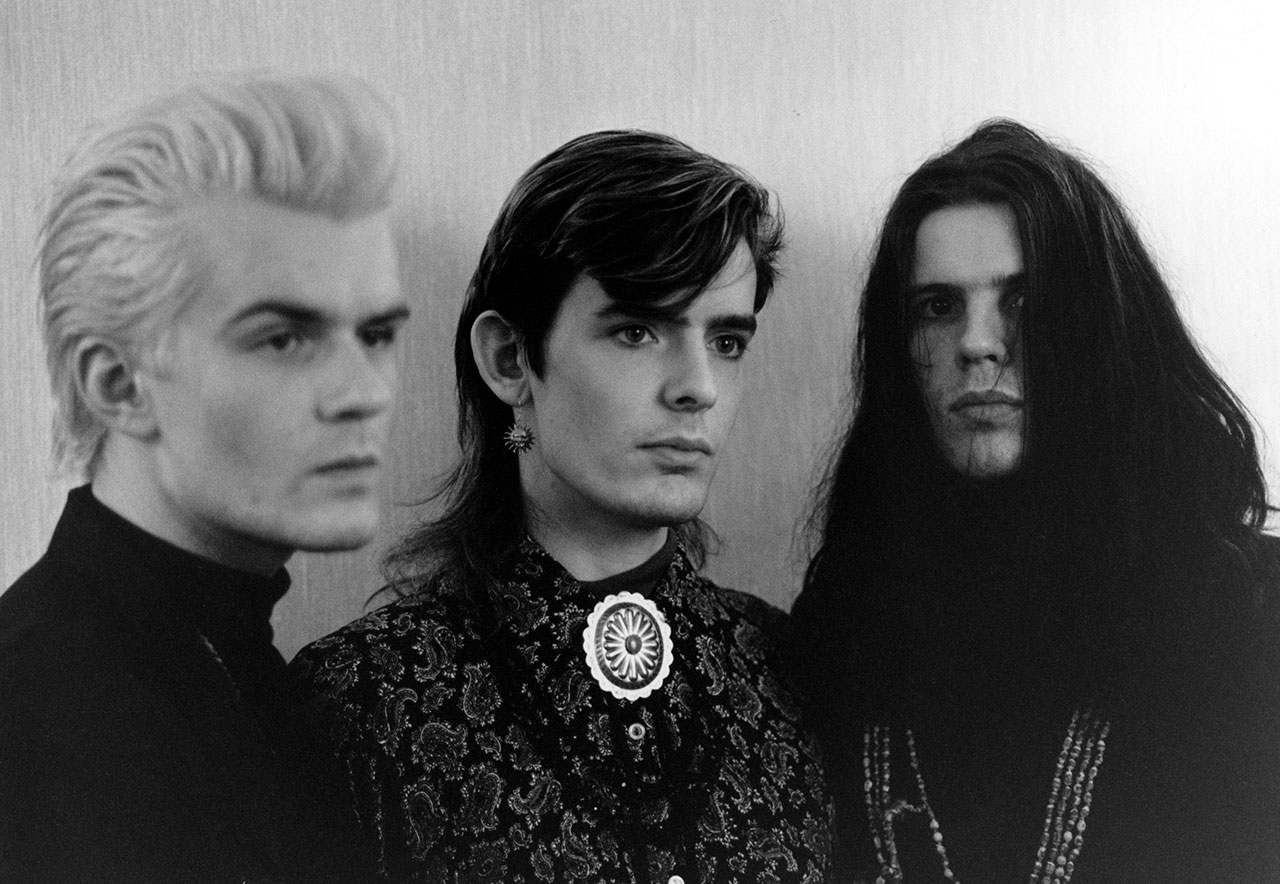

The story of The Cult is well documented, of course. Few of you will need to be reminded of frontman Ian Astbury’s early days as vocalist for Southern Death Cult or that, in 1982, he teamed up with ex-Theatre Of Hate guitarist Billy Duffy and embarked on a new and more ambitious creative endeavour. Initially labelled as Death Cult, the duo released a brace of EPs, shortened their name, released their impressive but decidedly non-traditional debut album Dreamtime in 1984, and began to prod purposefully at the lower end of the UK singles charts (and the top end of the then highly influential indie charts) with propulsive goth-tinged rockers like Spiritwalker and Resurrection Joe. In stark contrast to the majority of their goth peers, however, The Cult were swift to recognise that, somewhat ironically, being mere cult figures was a rather meagre aspiration and that bigger and better things were out there for the taking. Inspired by an increasingly intense adoration of the 70s classic rock bands that punk had often sought to discredit, Astbury and Duffy struck upon a new plan that would turn them into bona fide rock stars.

“There were certain guidelines in the post-punk, new wave movement, and that was to stay clearly away from long hair and guitar solos,” says Ian Astbury. “So for us that was like, ‘Great! That’s exactly where we’re gonna start!’ If that’s where we’re not supposed to be according to some erudite journalist, then that’s exactly where we’re starting. I wanted to find out what the taboo was all about. Then you hear Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin and The Doors, and suddenly it’s like, ‘What is this? We’re not supposed to listen to this? You’re kidding me!’ We’ve always had a punk rock attitude, but it’s less reactionary and more dynamic. Rebels respond to a situation in a way that’s not just being contrary, there’s a visceral and energetic response.”

Although Dreamtime was a strong album and one that had garnered plenty of critical praise, its blend of wild west macabre and post-punk tribal thumping made it seem more like a logical progression from Astbury’s Southern Death Cult days than any kind of tangential leap. The frontman’s fierce self-confidence and desire to create enduring art, rather than zeitgeist-chasing scene fodder, ensured that when The Cult came to make their second album, the wheels of progress were already in motion and punk’s haughty clarion cry of ‘Never trust a hippy!’ was being kicked brusquely into touch.

“We did our first ever big gig in 1984, co-headlining a festival in Leeds with Killing Joke,” Duffy recalls. “I remember that was when Ian unveiled his psychedelic look. I was still dressing like the guy with the shotgun in Apocalypse Now, who’d gone and started hanging out with Colonel Kurtz. I had that Vietnam tiger stripe, Clash-influenced Combat Rock kind of vibe and Ian was doing his gothic Mohican thing and then he just showed up at this gig and he had a paisley cardigan on and pink glasses! Ha-ha!”

As The Cult’s new material began to take shape, it soon became apparent that Ian Astbury’s image change was indicative of a more holistic focus shift, as those Led Zep and Doors influences began to infiltrate their band’s compositional process. The true watershed moment came when Astbury and Duffy hit the studio – with bassist Jamie Stewart and drummer Nigel Preston – to record a precursory single that was intended to get the ball rolling for the next full-length record. Shifting to Beggars Banquet Records from that label’s subsidiary imprint Situation Two, The Cult entered Olympic Studios in Barnes, London – which Led Zeppelin had used previously – hoping to team up with renowned rock producer Steve Lillywhite. Due to a slight miscommunication with their management company, the band ended up with former Wham! producer Steve Brown; a potentially calamitous pairing that irritated Duffy and amused Astbury no end. As it turned out, band and producer would develop a great and lasting chemistry, the recording of the aforementioned single – a catchy little number called She Sells Sanctuary – proving a potent starting point.

“Sanctuary came together very easily in fact,” Astbury stated in 2010. “I took the bass line from a song called Spiritwalker… Billy came up with the melody, and we worked out a vaguely psychedelic guitar sound which seemed to fit it well. We were heavily into 60s psychedelic music. The producer, Steve Brown, had had a lot of pop success so he really knew how to structure a song. It’s funny, you write a song like that where everything comes together far beyond what you could’ve expected and then you spend the rest of your life trying to write another one as good.”

Released as a single on May 17, 1985, She Sells Sanctuary was an instant hit in the UK and was embraced with great alacrity by both the few radio stations that played rock music and every single rock-centric nightclub in the country. Like many of their contemporaries, The Cult released an assortment of remixed versions of Sanctuary on then obligatory 12-inch singles, acknowledging that their sound was as much about moving feet on grubby dancefloors as it was about celebrating rock’s cerebral potential. That insistent, pulsing beat, Duffy’s mesmerising guitar hook and Astbury’s impassioned vocal had combined to create what is now widely regarded as one of the truly great rock anthems of the 80s and The Cult instantly outgrew their cult status as a result.

“Sanctuary is always a joy to play, even 25 years later,” Billy Duffy stated earlier this year. “No one ever bitches about playing it, Ian included, and he’s not the greatest lover of touring! We’ve never had a problem with Sanctuary. I’m happy we’ve got a song like that. Something like Fire Woman [from 1989’s Sonic Temple] is a very popular song around the world but it’s very challenging to play and sing and do. It’s not one that we like playing! That’s a bit of a chore to play, just the way it was written and constructed. Sanctuary’s just fun and rolls along.”

Transformed by its creators and Steve Brown from its considerably less dynamic original demo incarnation into a swirling storm of riff-driven psychedelia, She Sells Sanctuary eventually peaked at number 15 in the UK singles chart, a feat that ensured that The Cult’s second album was already fated to be a big deal. Unperturbed by the departure of drummer Nigel Preston (whose shoes would be filled in the studio by Big Country’s Mark Brzezicki), the band entered Jacobs Studios in Farnham, Surrey, with Brown once again at the controls, and began to sprinkle the same magic over the rest of their new songs. Egged on by Brown, who swiftly realised that Astbury and Duffy would have to be physically restrained from coming up with a relentless stream of ideas, Love took shape over four feverishly productive weeks in the summer of 1985. Although often spawned by extended jams and pieced together from several takes to create one perfect whole, the likes of dark disco tone-setter Nirvana, surging son-of-Sanctuary second single Rain and the rumbling swing-metal of Big Neon Glitter amounted to the perfect fusion of classic rock swagger and spine-tingling post-punk intensity. The Cult were discovering the true depth and versatility of their newly enhanced sound, too. Whether whipping up a densely atmospheric storm of sinister melodrama on the epic Brother Wolf, Sister Moon, throwing the mellifluous tones of female backing vocal troupe The Soultanas into Revolution’s strident brew or raising hallucinatory hell on the wild histrionics of The Phoenix, Love showcased a band brimming with self-belief and a genuine desire to tap into rock’n’roll’s effervescent essence while fearlessly striding into virgin territory.

“I admit that what we were doing was fairly controversial at the time,” Astbury later stated. “It was controversial to be punk rockers and still love Led Zeppelin, and to call an album Love in the aggressive post-punk era was seen as potential suicide. These things drew a lot of heat from the media but, worse still, I remember going out when She Sells Sanctuary got in the charts and some kid came up and punched me right in the face at a concert. There was so much hatred in his eyes, and all that was because we came from the streets in Brixton, we came from punk rock and I think this guy saw us as breaking the code by not pretending we couldn’t play our instruments or for having success.”

Despite upsetting a significant proportion of their diehard goth and post-punk fanbase by so proudly proclaiming that allegiance with rock’n’roll tradition, Love was an instant and substantial hit in the UK, rapidly becoming Beggars Banquet’s best selling album ever and steadily establishing The Cult’s status as the UK’s brightest new rock hopes on the other side of the Atlantic. That shrewd but sincere combination of otherworldly eclecticism and more familiar and widely revered rock’n’roll elements immediately struck a chord with American rock fans. By the time the band started thinking about a follow-up to Love, their subsequent reinvention as a convincing arena rock behemoth, courtesy of the Rick Rubin-produced Electric, was practically a done deal. Even so, Ian Astbury remained wary of any attempts by outside forces to pigeonhole his band or restrict their creative desires.

“We came to the United States in 1984 with the Dreamtime record,” Astbury said in 2010. “The band was very much entrenched in the genesis of the American post-modern scene. Then we came back and did another tour with Love. The CMJ Awards gave us Single Of The Year for She Sells Sanctuary and we were on Saturday Night Live, too. We were very much an independent, post-modern band. But as soon as people started putting that tag or that stigma on us, we very naturally gravitated toward something else, because we’d done that and we’d said that.”

Twenty-seven years after its release, Love has shifted in excess of two million copies worldwide and has been reissued, repackaged and reassessed on numerous occasions. The Cult have made many great records over the years, but this is the one that continues to define the band in the eyes and ears of their most ardent admirers. Proof that instinct and conviction are far more powerful and worthwhile artistic tools than cynicism or puritanical tyranny, Love continues to resonate because it dared to be a balls-out British rock album at a time when such values were routinely viewed with suspicion. Above all, Love is an album of great and ageless songs played by one of the greatest bands of this or any age.

“The good thing about the songs on Love is that they deal with things that are no less relevant now than they were then: life, death, sex, materialism, spiritualism; all the human experiences,” Astbury recently surmised as he looked back on the album that made him a worldwide star. “Creating Love, we were trying to make a flower instead of a barbed-wire fence. That took a real presence to do that.”

This article originally appeared in Metal Hammer Presents: The Cure And The Story Of The Alternative 80s.