Six days before Christmas of 1986, Dave ‘Snake’ Sabo received what he thought was the best present a young guitarist could possibly dream of getting. His childhood pal, fellow New Jerseyite Jon Bon Jovi, had invited Snake’s fledgling hard rock group, Skid Row, to open the first three shows of the North American arena tour in support of Bon Jovi’s breakout hit album, Slippery When Wet.

At the time, Skid Row were unsigned, but Snake hoped the Pennsylvania performances alongside one of rock’s hottest acts would help to change that.

Unfortunately for Snake and his bandmates, Bon Jovi manager Doc McGhee – who’d recently guided Motley Crue to stardom – would soon play the role of The Grinch.

“It was exciting playing in front of 7,000 people, sold-out, with one of my best buds as the headliner,” Snake remembers. “Then Doc comes into the dressing room and goes, ‘The band’s great; the songs are great; but you need a singer. He’s not the guy. He’s not a star.’”

Soon after, Skid Row fired their vocalist, Matt Fallon, and began a nine-month search for a replacement. After numerous fruitless auditions, a friend of Snake’s told him about a memorably named singer he’d seen perform at a wedding: Sebastian Bach, a tall, razor-lunged Canadian teen who’d previously fronted the groups Kid Wikkid and Madam X. Snake subsequently sent Sebastian a four-song cassette of Skid Row demos that included early versions of 18 And Life and Youth Gone Wild.

“I kept listening to the tape because I couldn’t get those two songs out of my head,” Sebastian recalls. “I said if I could reinvent the melody lines – especially in 18 And Life – and put in some Halford-esque kind of notes, I could make this into something that I would really be proud of.”

Sebastian soon flew from Toronto to New Jersey to audition in person – or at least, that was the original plan. After a short introductory meeting at Snake’s mother’s home, the band took Sebastian to a local nightclub called Mingles.

“We ended up getting really, really hammered and commanding the stage,” says Snake. “That was the first time the five of us played together, and we announced onstage that Sebastian was the new singer of the band. We were terrible, but we knew there was something magical about it.”

From there, Sebastian moved in with bassist Rachel Bolan. “We rehearsed every day in Rachel’s parents’ garage,” Sebastian says. “We had space heaters because it was so cold in there, but we didn’t even discuss it. We had a work ethic that was just natural to us, and we were always in the garage, working on tunes.”

Eventually, Bon Jovi invited his manager to check out Skid Row’s new vocalist in person. Says Snake, “Everyone was like, ‘I think you’ve got something here.’ Everyone was a believer in the songs that we were writing and the vibe of what we had created. We were just missing that last piece – Sebastian.”

Doc McGhee agreed to manage the band and helped them score a record deal with Atlantic. The label paired the group with Michael Wagener, a German producer who had previously worked with Metallica, the Crue and Accept. “I liked them instantly,” Michael says. “I knew the band would be able to go somewhere. They were all 100% musicians and very, very dedicated.”

Skid Row recorded their debut album with Michael in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, a resort town 90 minutes from Chicago, in a studio located next to a convention centre and two golf courses. Also located nearby was the 37,000-capacity Alpine Valley Music Theatre, where the band saw Def Leppard perform during their tour in support of Hysteria.

“They could not have been nicer,” Snake says. “Phil [Collen, guitarist] came down to the studio, like, ‘Hey, I’m taking a helicopter over to the amphitheatre. Do you want to come with me?’ I flew with him over to do soundcheck. When they were leaving, they brought us a bunch of bottles of champagne and wished us luck.”

We went in Def Leppard’s helicopter and they bought us champagne

Dave 'Snake' Sabo

According to Michael, the recording sessions – which saw the band track drums inside the adjacent convention centre, creating a natural reverb effect – ran smoothly. “They were all professionals, from the first day on,” he says. “To this day, it’s still my favourite record that I recorded.”

Snake, however, remembers one bump in the road. “One of Michael’s things was that nothing leaves the studio without his permission,” he says.

“We were doing I Remember You, and Sebastian snuck a cassette out and played it for some people. Michael found out about it, and the next morning he went to Sebastian’s room, screamed at him, grabbed the cassette and threw it in the microwave!”

He recalls Michael fondly. “He was the dad overseeing a bunch of kids running around in the sandbox, making order out of chaos,” he says. “He was a huge factor in that record being what it is, because he extracted those performances out of us.

"They didn’t just happen – they were pulled out of us by Michael. When we felt we were there, he’d go, ‘Well, it’s close – but I know you’ve got one more in you that’s better.’”

Released in January 1989, Skid Row’s 11-track, self-titled debut is something of an anomaly. It sounds very much in line with the popular hard rock of the era – Rolling Stone even ranked it fifth on their list of the ‘50 Greatest Hair Metal Albums Of All Time’ – yet shows more teeth than its competition.

For every Big Guns or Can’t Stand The Heartache, there was a Piece Of Me or Youth Gone Wild – one reason why the band found themselves equally at home supporting Bon Jovi and Aerosmith as they did in later years touring with Guns N’ Roses and Pantera.

“With that first record, there’s so many different voices commenting on what songs should be on there and what songs shouldn’t be, and it all plays a part in the definition of who you are,” Snake says.

“You’re just running on your gut and on your trust of others, and figuring out, ‘Who is Skid Row?’ You certainly get advice and whatnot, but there’s no set blueprint. You’re just figuring it out as you go along.”

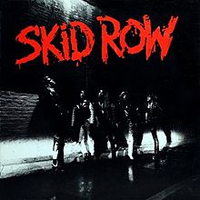

The album also stood out visually, with its dark, black-and-white cover contrasting sharply with the colourful illustrations or glammed-up band photos of their peers. “It was conscious,” Sebastian says.

“I remember being confused, because everybody else was like the [1984 glam metal band] Vinnie Vincent Invasion – glitter and the biggest hair and make-up and colour – and Skid Row came out black and white. I go, ‘It looks like a mistake – you can’t even see us. It’s just shadows.’ But it was absolutely perfect.”

Two days after the album’s release, the band hit the roads of North America with Bon Jovi – a tour that ended six months later, ironically, at Alpine Valley. Soon after, they performed at the McGhee-organised Moscow Music Peace Festival, before making their UK debut alongside Bon Jovi at the Milton Keynes Bowl.

“We all had the image of England being rainy and wet and cold and grey, but while we were on stage, it was sunny, beautiful and gorgeous – the best weather you could ever imagine,” Sebastian remembers.

He screamed at Sebastian and threw the cassette in the microwave

Dave 'Snake' Sabo

Three months later, the group headlined a sold-out Hammersmith Odeon. “I looked over at the monitor board, and standing next to Doc watching us play was Robert Plant,” Sebastian recalls. From there, the group returned to the States to support Aerosmith.

On the tour’s seventh stop, in Massachusetts, Sebastian proved he was a youth gone wild by heaving a glass bottle that had been thrown at him back into the crowd, injuring a young fan. (In his 2016 autobiography, he expresses regret for being a “total asshole” that night.)

Still, nothing – even Sebastian’s unfortunate decision to wear a t-shirt saying ‘AIDS Kills Fags Dead’, for which he subsequently apologised – seemed to be able to derail Skid Row’s success.

Less than a year after its release, their debut album was already triple-platinum in America, where it peaked at No.6. Two of its singles – 18 And Life and I Remember You – cracked the US Top 10 and the UK Top 40. The band’s follow-up album, 1991’s Slave To The Grind, would do even better initially, debuting at No.1 in America – the first ever heavy metal album to do so – and at N0.5 in the UK.

As quickly as Skid Row rose to fame, however, the group’s fall was nearly as rapid. Shifting musical trends and bad blood between Sebastian and his bandmates saw the parties part ways in 1996, and, according to the singer, they haven’t even been in a room together since.

Over the past two decades, Sebastian and Skid Row have continued to tour the world separately, performing many of the songs from the band’s debut. Skid Row played this year’s Download Festival, albeit with former Dragonforce vocalist ZP Theart, who officially joined in 2017.

Snake knows such gigs wouldn’t be possible without fans’ continued reverence for the material on the group’s classic debut. “I am absolutely humbled by it, and I have so many great, amazing memories of that period of time,” he says.

“Things turn out the way they turn out, but you cannot take away what existed and what we’ve all been through together. You have to embrace the history of it, regardless of where we all are as individuals separately and collectively.”

Sebastian voices similar sentiments. “Music has a life of its own, and this album isn’t my album – it’s the whole world’s album,” he says. “This music has transcended what we ever could have envisioned for it.”

Inside Skid Row

Three choice cuts from their explosive, self-titled debut...

The Hit: 18 And Life

The album’s third single – a true crime ballad-with-teeth about a young boy with a heart of stone who was serving a life sentence for murder – solidified the band as MTV darlings. Three decades later, the goosebump-worthy guitar solo and Sebastian’s piercing high notes remain just as haunting as the song’s narrative.

The Classic: Youth Gone Wild

This impassioned rallying cry for alienated teens wasn’t just an anthem of rebellion, but also unity (‘we’re one and one for all’). In addition to a triumphant riff and a gnarly, squeal-filled solo, it also features what’s arguably the coolest self-referential line in rock history, as Sebastian reminds listeners just where Park Avenue leads.

The Wild Card: Rattlesnake Shake

On an album with no shortage of motley characters (Ricky in 18 And Life, T-Bone Billy in Makin’ A Mess, the Subway Queen in Sweet Little Sister), this song’s Tricky Little Vicky and especially Juicy Miss Lucy (‘talk is cheap, and so is she’) take the cake.