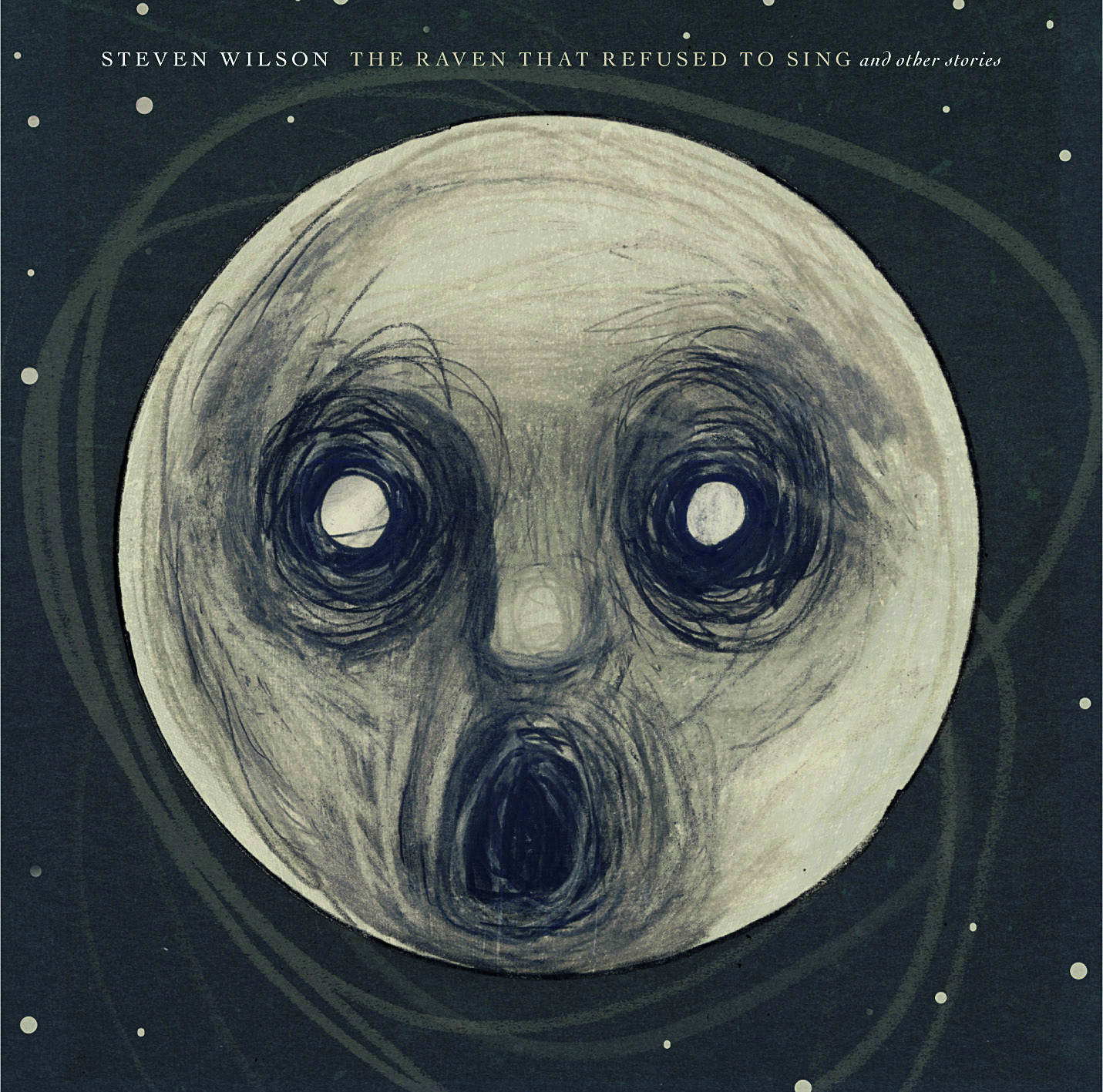

The story of Steven WIlson's The Raven That Refused To Sing (And Other Stories)

Released in 2013, Steven Wilson's third solo album The Raven That Refused To Sing (And Other Stories), an album of ghost stories, continued his upward trajectory

Sauntering barefoot through a Los Angeles graveyard, Steven Wilson pauses to pull out his iPhone. “Have you ever been to Milan? Milan has my favorite cemetery of all time,” he says, holding up his phone to scroll through photos of the Italian city’s Monumental Cemetery. “It kind of reminds me of this place.”

Nestled against the edge of Paramount movie studios, the Hollywood Forever Cemetery is where mortality meets vanity. Its ornate gravestones, epic mausoleums, and vast crypts are the final resting place of Hollywood legends such as Douglas Fairbanks, Cecil B DeMille, and Rudolph Valentino. By day, it’s an idyllic Eden with tall palm trees that arc into the sky like green flares. Come nightfall, even Stephen King might fear to tread here. The famous graveyard hosts a ghoulish annual festival called ‘Dia de Los Muertos’ (Day of the Dead), regularly screens horror movies, and occasionally acts as a macabre venue for rock concerts. “Cool place to have a gig,” muses Wilson. “Sigur Rós apparently played here.”

The graveyard would be a perfect haunt for Wilson to perform his new album, The Raven That Refused To Sing (And Other Stories), which is about the supernatural. Although the album is concerned with death, it’s given Wilson a whole new lease of life.

“The ghost stories I’m using on my record are the kind of old-fashioned ghost stories,” says Wilson, his voice animated with boyish excitement. “These are almost Dickensian or Victorian ghost stories. I remember hearing A Christmas Carol on the radio, a good old-fashioned ghost story, but it’s much more than that. It’s about affirmation of life. It’s the original ‘seize the day’ story, isn’t it? Seize your life and enjoy it! It’s the idea of using mortality as a way of reaffirming life.”

That carpe diem attitude sums up Wilson’s thinking these days. Indeed, his ethos might be best summed up by the motto on one of his favourite black T-shirts: Enjoy Life With Music. It’s no wonder, then, that Steven Wilson’s third album, his second consecutive solo album, brims with improvisation and risk. The break has emboldened him to not only completely change his recording process, but also explore areas of progressive music far beyond the remit of a band like Porcupine Tree.

“I have entered a whole universe of my own where the music doesn’t seem to obey any rules anymore,” enthuses Wilson. “It’s more bloody-minded, it’s more selfish, it’s more pure; it’s more spiritual. There’s more of a jazz sensibility in it, which is something I think was always missing from my previous records.”

Don’t worry; Steven Wilson hasn’t made a George Benson record. When Wilson references the new-found jazz influence on his solo work, he’s thinking in terms of albums such as Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew, King Crimson’s Lizard, and Mahavishnu Orchestra’s Birds Of Fire. “When people see the word ‘jazz,’ they suddenly think I’m going all sort of noodle-y,” says Wilson. “That wasn’t the idea.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The plan behind The Raven That Refused To Sing (And Other Stories) was, however, to recreate the spontaneous spirit of those classic recordings.

EastWest Studios is on Sunset Boulevard, just a two-minute drive from the Hollywood Forever Cemetery. On the outside, the rectangular building is as white as a wedding cake and nearly windowless. Its cloaked anonymity means that most people pass it by without noticing it. Inside, however, EastWest resembles the lair of a vampire coven. Its narrow corridors are swathed in waterfalls of red curtain. Other walls are lit in Wizard Of Oz green. The overall effect is gothic chic. It possesses the appropriate ambience, in other words, for Steven Wilson to record an album about supernatural stories.

Wilson’s band—Theo Travis (sax, flute), Adam Holzman (keyboards, piano), Nick Beggs (bass, Chapman stick), Marco Minnemann (drums) and Guthrie Govan (guitar)—recorded seven songs in seven days in Studio Two, a high-ceilinged room lined with wood paneling in autumnal hues. (One of those songs, The Birthday Party, didn’t make the album but will likely surface as a bonus track.) Like many of the great jazz-rock albums that Wilson admires, The Raven... was recorded live in the studio. It’s a radical departure from how Wilson has made all his albums, including his two previous solo efforts, Insurgentes (2008) and Grace For Drowning (2010). To that end, Wilson hired the legendary Alan Parsons to engineer the recording sessions.

“What you hear, apart from my vocals, is a live band playing,” says Wilson. “Can you believe that? In 20 years of making studio records, I’ve never done that before. I’ve always cut the drums, you bring the bass player in and you cut the bass parts, and then add the guitars and the keyboards. And it’s all done to a click track and everything’s edited and put perfectly in time. That’s not the way those guys were making records. And, as I began to understand that, I think my music began to get loose again.”

The result of that modus operandi is an album that brims with livewire tension. You can hear it on the epic centrepiece, The Watchmaker, which nods toward Floyd’s Shine On You Crazy Diamond and recounts the literally haunting tale of a murderer who faces a day of reckoning from the ghost of his murdered wife. The track begins with pastoral acoustic guitar, harmony vocals, flute, and piano. But the barometric pressure of the piece changes once all the instruments coalesce like a gathering storm. It climaxes with a furious cyclone of corkscrewing guitar and saxophone. At the very end, the song dissipates with a quiet piano outro.

“Steven was trying to infuse prog with some of the kind of musicianship and attitude you would expect to hear in 70s fusion,” says guitarist Guthrie Govan. “For me, that’s pretty much the best of both worlds—maintaining a ‘prog’ kind of discipline and structure, but also featuring some looser, more free-form moments where the band members are interacting with each other in real time.”

In 2013, that approach to recording is virtuously old-fashioned. Similarly, prog, fusion, and jazz are hardly mainstream. Good luck finding such fare represented on, say, Later... with Jools Holland. No wonder Wilson is perplexed by today’s music scene.

Perhaps the most visited grave inside the Hollywood Forever Cemetery belongs to Johnny Ramone. The plot boasts an impressive bronze statue of the leather-jacketed punk leaning back with a guitar, his fringe covering his eyes.

“Not really a fan,” says Wilson as he walks around the cenotaph of the musician who died of cancer in 2004. “I like the idea of it more than the execution of it. Once you’ve heard one song, you’ve heard them all.”

The Ramones’ break-out year, 1977, was when the punk proletariat violently overthrew rock’s reigning czars. Wilson still laments the end of the golden era of music, which, he says, was more radical and experimental than post-punk fare, including most modern music. That belief was reaffirmed when he remixed King Crimson’s Lizard and Islands. “I was listening to those Crimson records and I was thinking, ‘This music is extraordinary.’ It obeys no rules. It creates its own rules. That’s the kind of record I want to make.”

Seeking a respite from the unrelenting Los Angeles sun, Wilson spots a stone bench under a willow tree. It’s situated on the gravesite of ‘scream queen’ actress Fay Wray, most famous for her role in the original King Kong. “Shall we sit down on Fay Wray?” grins Wilson. Once settled, Wilson explains that he tried to emulate those early King Crimson albums by combining jazz and rock musicians on his album.

“The idea was to somehow capture the spirituality and improvisational qualities of jazz and to therefore make the rock musicians play in a different way, too,” Wilson says. “My role model was Frank Zappa. Here was a guy that always employed extraordinary musicians and allowed them, in a way, to exert their personality on his music while still controlling everything in quite a tight way. What you do as a bandleader in this context is you employ a musician and you figure out what you like about his style. And then you write music that harnesses that. That’s what’s so exciting about this record for me. Grace For Drowning was written for musicians in the abstract. This album is written for specific musicians.”

Case in point: the opening track, Luminol, is a showcase for Adam Holzman, a virtuoso jazz keyboardist who has a collection of black T-shirts to rival even that of Wilson. “I was very committed to a jazz player who favoured Fender Rhodes, Hammond organ, and Mellotron, what I call the ‘golden, organic’ sounds,” says Wilson.

Theo Travis gets a spotlight moment on The Holy Drinker. “There is a heavy and dark, Led Zeppelin meets Miles Davis vibe,” raves Travis. That track also includes a soprano sax solo that, for all its sweet tone, possesses drill bore intensity. Indeed, despite the absence of the depth-crush guitars that is a staple of Porcupine Tree, the solo artist observes that parts of his new album are “fucking heavy.” At one point, Wilson even tried to convey the desired intensity of a song by asking the musicians to “imagine a troll who’s lost his passport.” (This, after all, is the same man who wrote a Porcupine Tree song called Message From A Self-Destructing Turnip.)

“The heaviest sections are not played by heavy metal guitars or the heavy metal vocabulary, they’re played by things like baritone saxophones, distorted Fender Rhodes pianos, overdriven Hammond organs, glockenspiels, fuzz bass,” says Wilson. “I would say, because of all that, they actually have more impact.”

The two men who help bring the heavy are drummer Marco Minnemann and bassist Nick Beggs. The flaxen-haired Beggs has been known to wear a kilt in concert even if there’s a fan on stage. Not very shy at all, in other words, except for when Prog tries to asks him about working with Wilson. “Mr. Wilson says that a loose tongue can ruin a mix and that there is no such thing as country music,” jokes Beggs in cryptic response.

The engine of the band, however, is unquestionably German drummer Marco Minnemann, who marries the timekeeping of an atomic clock with the wild abandon of Keith Moon.

“He makes you laugh because he does things that are so crazy,” says Wilson. “I say to him sometimes, ‘Sorry, I couldn’t look at you today, Marco, because if I had, I’d have just been laughing all night.’ He has that incredible joy.”

The newest addition to Wilson’s band is Guthrie Govan, a guitarist who has been lauded by the likes of Steve Vai, Joe Satriani and Paul Gilbert. On the ballad Drive Home, Govan plays an astonishing outro that combines passionate feel with finger-pretzeling technique. Wilson calls it one of the greatest guitar solos ever recorded. Not bad for a first take.

As Govan tells it, “The LaRose guitar company had sent Steven a new guitar on the day of the Drive Home session: it looked a lot like a Fender Jazzmaster, but it had a solid rosewood neck and a Sustainiac pickup (essentially an EBow type device for generating infinite sustain, but mounted in the body of the guitar rather than in an external hand-held gadget). I’d never played a guitar with a Sustainiac before, so I was keen to try it out. I hadn’t really checked the way the guitar had been set up, so the top E string was prone to popping out of the bridge whenever I hit it too hard, rendering it all but unusable. It did just that at one point during my solo but... well, Keith Richards always seems to cope with just five strings, so I figured it would be churlish to let a little mishap like that ruin the whole take! We recorded a few more after that, and they probably sounded more ‘perfect’ but... there was something about the spirit of that first solo.”

“I’ve always thought about mortality,” says Wilson, admiring a temple-like crypt situated on a small island in one of the cemetery’s duck ponds. “The more you love life, the more you’re obsessed with mortality and death.”

Quotes such as that one may lead fans to believe that Steven Wilson is a morose fellow. It doesn’t help that even Rush’s Neil Peart smiles more on camera than Wilson does in his publicity photos. However, Wilson is usually very upbeat and ever keen to make others laugh. A glimmer of Wilson’s perverse sense of humour comes through in Luminol, the first track on the album. It’s a ghost story that arose from the most unusual of inspirations: a lowly street musician.

“It’s based on someone who is a busker where I live. He’s in the high street every day. He’s terrible! He never ever seems to get any better and he never gives up. I had this idea: maybe one day this guy is just going to die of hypothermia or something. And even when he dies, he’s still going to be there. So it’s this idea of this busker that dies and doesn’t realize that he’s dead and just carries on performing in the street.”

Other stories are more wistful, sad reflections on the unbridgeable gulf between the living and the dead. “I think the idea of death and the afterlife and ghosts teaches us a lot about living,” Wilson says.

The subject of ghosts, both literal and figurative, has been a prominent lyrical theme throughout almost all of Wilson’s projects (alongside his enduring fascination with trains, serial killers, and failed relationships). In 2005, Porcupine Tree created Deadwing, a concept album whose fragmented narrative was based on an original ghost story that Wilson hopes to make into a movie. Other examples include Bass Communion’s Ghosts On Magnetic Tape, No-Man’s Schoolyard Ghosts, the title track of the first Blackfield album, and Wilson’s solo cover version of the traditional folk song The Unquiet Grave. It comes as a surprise, then, that Wilson doesn’t actually believe in ghosts.

“Here’s the thing: I want to believe in ghosts. I love the idea of someone leaving a spiritual impression behind. I do think, somehow, that happens. It’s a scientific thing, not a supernatural thing. I think that the soul, or an energy, or whatever you want to call it, remains after someone has left. You feel it in a room that a person has been in a lot.”

Wilson commenced writing his third solo album less than a year after his father died. He can still feel his dad’s energy in his old study even though his possessions have been cleared out.

“Inevitably, when one of your parents goes, you realise that you’re next,” says Wilson. “I realise now that I am probably closer to the end of my life than I am to the beginning of it.”

Wilson has been pondering the meaning of life for a while now. For instance, Porcupine Tree’s 1996 album Signify was about the ways people try to find significance in their lives, whether it’s through religion, drugs, sex, or spending life on a computer. If anything, his father’s death has made him realise that he doesn’t want to spend his entire life working. He’d like to do some proper travelling someday. To underscore the point, Wilson laments that he’s been to Venice three times but he’s only seen the inside of the airport, the tour bus, and the local concert venue. And, several decades from now, his envisages a new life as a producer—that is, he quips, if people are still making records in 20 years.

“It’s a very hard thing to make sense of life and what you’re supposed to do with your life,” muses the musician, gazing at a turtle that has periscoped its head above the pond water. “Are you supposed to lay on a beach your whole life? I don’t think mankind or womankind finds that an easy thing to do. I think we feel we have to have some kind of raison d’être, don’t we? We seem to feel the need to have some purpose for our actions.”

So what gives Wilson’s life meaning?

“In a way, it goes back to one of your earlier questions: Do I still think people will be listening to my music in a hundred years’ time? I’d like to think so because, in a way, I’d like to think my life has had some significance and purpose beyond mere self-gratification.”

With that, the musician begins to tie his shoes laces so that he can return to the studio, where Wilson, for once, is happy to let his band play such a prominent role in the making of his new album, you wonder where Wilson sees himself fitting in.

“I’m very happy to be standing there, playing relatively little but conducting and directing,” he says. In truth, he’s downplaying his role as a musician on the album. Wilson contributed some bass and even played the original Mellotron used on King Crimson’s debut album. Govan observes, “You’ll certainly hear some of Steven’s guitar parts on the record, certain EBow melodies and all of the acoustic guitars, for instance. If you hear two guitars playing simultaneously at any point on the record, one of them is Steven’s and the other one is mine.”

“It’s all written by me, it’s all produced by me, obviously, I’m still singing, but in terms of performances of the music, I’m happy to let these guys play because they can do some things that I can’t do,” says Wilson.

What they have enabled him to do, however, is to finally fulfill his carpe diem vision: "I think things have changed, I feel like this is the time in my life when I want to make the kind of records which are astonishing, extraordinary, confrontational, difficult, inaccessible, ambitious, pretentious, and, maybe, over-the-top.”

One last question: Would Wilson ever want a gravestone or memorial like Johnny Ramone?

“In a way my own ego would probably like some physical monolith to my life,” chuckles Wilson, “The little bit of humility that I do have says that, actually, that’s just ego. It doesn’t matter.”

Steven Wilson may not wish to be buried in a cemetery, but if he were to have a gravestone it might be inscribed with the following epitaph: Enjoy Life With Music.

This article originally appeared in issue 33 of Prog Magazine.