It’s an October night in 1992 in Asbury Park, New Jersey, and the salty wind is blowing in off the ocean. Bruce Springsteen made his name writing about these mean streets, although that’s not what the Screaming Trees are thinking about as they mill around in front of a bar named The Fast Lane.

None of the Seattle band are what you’d call small; drummer Barrett Martin is over six feet tall, and the rest of them – 300lb guitarist Gary Lee Conner and his equally hefty bassist brother Van Conner, plus singer Mark Lanegan – loom over him. But that doesn’t stop a gang of locals rushing them as they stand outside.

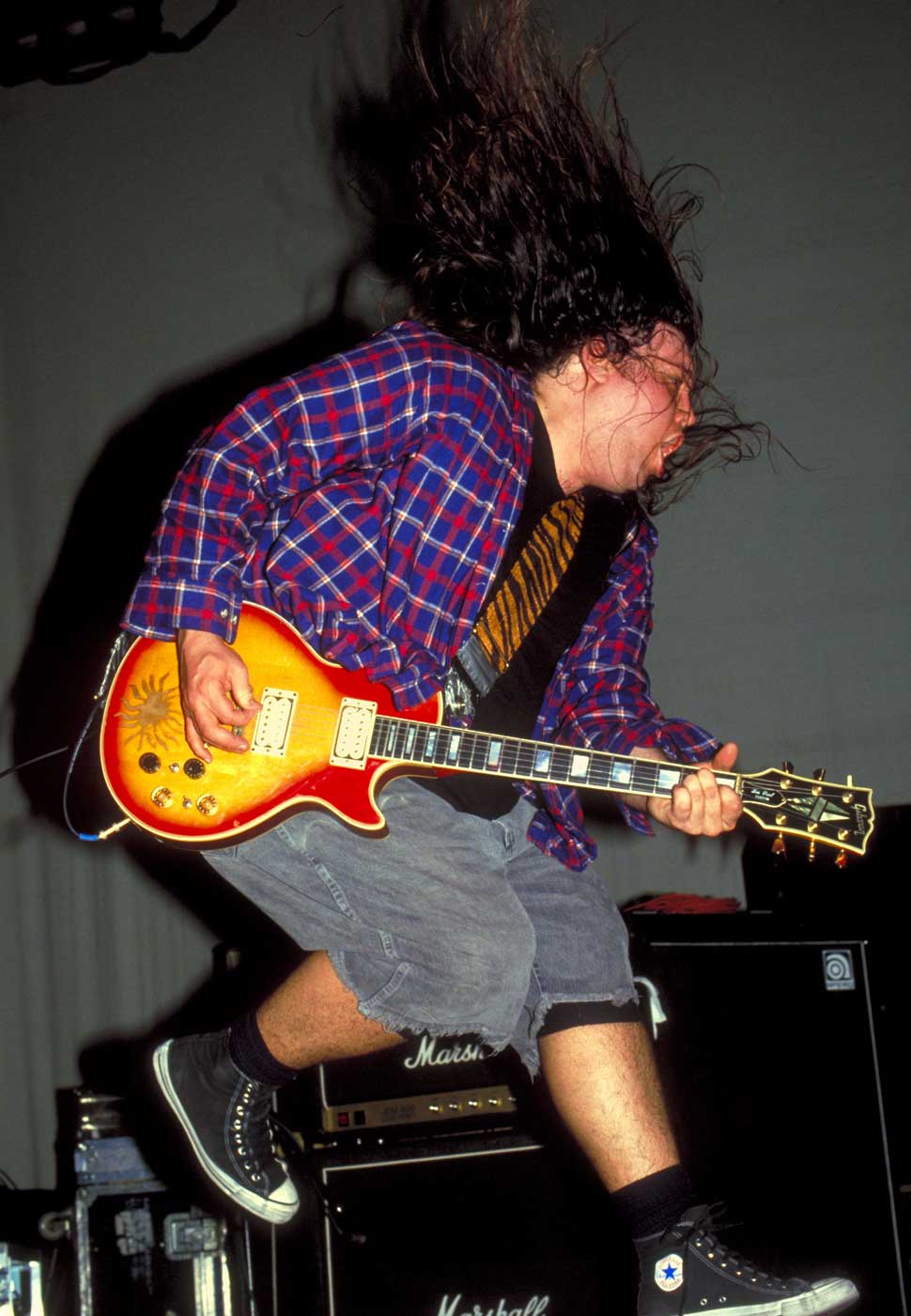

The Trees are scrappers from way back, not least among themselves. They’ve never gone down in a brawl, and they’re not about to start now. Fists fly back and forth between the flannel-clad musicians and the bunch of local meat-heads, until the latter realise there’s going to be no satisfaction from trying to take down a gang who steadfastly refuse to fall. The gang disappear into the night, the only sign they were ever there being the cuts and bruises left on the bemused band members.

They check themselves for damage. Mark Lanegan sweeps back his mane of hair to reveal a shiner around his eye. Barrett Martin realises that he can’t raise his arm; he’s dislocated his shoulder. None of this would normally be a problem – they’ve been in plenty of fights before. But tomorrow night the Screaming Trees are due to make their national TV debut on Late Night With David Letterman.

They do make it, even if it’s not quite in one piece. Watch their performance of hit-single-that-never-was Nearly Lost You on that show now, and Lanegan looks like he’s been staring through a telescope with ink around the eyepiece. But he fared better than Martin, who didn’t even make it on set. They look and sound as ferocious as a band who had been in a bar brawl 24 hours earlier should look. But while that sort of thing is fine on the stage of some club in Washington state, it doesn’t sit so well on national TV.

The Letterman appearance encapsulates the Screaming Trees’ proven ability to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory. Between 1985 and their split in 2000 they released seven albums, at least two of which should have made them as big as their more celebrated Seattle peers. That they never made it was down to any number of things: drink, drugs, in-fighting, image, bad timing or bad luck. Maybe a combination of all of them.

“We didn’t have a damn thing in common except insanity,” Mark Lanegan said later. “So we fought a lot.”

Things were quiet in Ellensburg, Washington in the late 70s and early 80s. A small logging town 107 miles east of Seattle, it was home to Gary Lee Conner and his younger brother Van, as well as Mark Lanegan. Today, Van Conner remembers the town as a refuge for under-achievers; for Lanegan it was a place where if you weren’t working a shitty job, then you were drinking or listening to music.

The young Conner brothers spent every spare cent they had on records. On a shopping trip in 1981, while still in high school, they picked up a copy of Black Flag’s pummelling Damage. It was like nothing else they’d ever heard. By Van’s admission, it opened him up to music completely.

By contrast, Mark Lanegan was a high-school quarterback who fancied himself as a future sports star, even if his background suggested otherwise: by the time he was 18 he had been arrested several times for various misdemeanours, including public drunkenness, shoplifting and – prophetically – drug possession (the last time he was arrested, he dodged jail only by agreeing to spend a year in a treatment program). But while Lanegan was a jock, he too loved music. He and Van would occasionally meet up to pore over the singles they’d both bought.

After leaving high school, Van and Gary Conner experimented with a series of short-lived bands with drummer friend Mark Pickerel. Lanegan would join them to chug beer and jam. Soon they realised that he was a better singer than Van. For the band, Lanegan’s wounded, menacing whisper was an epiphany; future Screaming Trees/Nirvana producer Jack Endino would later call him the best singer in Seattle. Not that Lanegan’s presence helped them get noticed.

“We couldn’t even get a gig in Ellensburg,” Gary Lee Conner recalls of the nascent Screaming Trees. “People thought we were complete shit. We didn’t even know how to write songs. But I put some stuff on my four-track and played it for Lanegan, and he thought we should actually try and do something with them.”

No one knew what was cool, or cared. The four of them would listen to Hüsker Dü and AC/DC. Later they’d cover the Small Faces song Song Of A Baker, and Van would call his son Ulysses after Cream’s Tales Of Brave Ulysses. They ploughed these disparate influences into a demo, 1985’s psychedelia-tinged Other Words, released by local label Velvetone.

The Conners’ parents lent them money to record the following year’s full-length debut, Clairvoyance. To their surprise, it sold 2,500 copies – impressive for a band from the backwaters of the Pacific Northwest in the pre-grunge 80s.

With nothing to fall back on, the Trees threw themselves into the life of a touring underground rock band. They spent the next few years criss-crossing the US in a van for months at a time, playing every night and sleeping on strangers’ floors. Then they’d head home to Ellensburg to work and save up to make another record and tour again. Lanegan, for one, took a number of jobs picking peas, building fences and working in the Conner family’s video store where the band also rehearsed.

By the end of the 80s the Trees had released another three albums: 1987’s Even If And Especially When, 1988’s Invisible Lantern and 1989’s Buzz Factory, all on pivotal US underground label SST. But tensions were growing. That Gary Lee Conner insisted on writing most of the band’s material was causing consternation. As Lanegan would recall: “He was really into a psychedelic thing, which I wasn’t into. He hadn’t even eaten acid, which I’d been selling for a number of years.”

The problems often turned physical. During sessions for Buzz Factory (which turned out to be their final record for SST), producer Jack Endino was surprised to walk out of the control room to see Van and Gary Lee wrestling on the floor. “I had to run out and move a bunch of mic stands,” says Endino, “It was like Clash Of The Titans. I looked at the other guys in the band and they were, like: ‘Yeah, they do this all the time.’ It was scary and serious, but it was funny too.”

Seattle in 1990 was a city on the brink. Soundgarden’s Louder Than Love and Nirvana’s Bleach had turned heads the year before, while Mother Love Bone’s march to success had been halted only by the untimely death of their singer, Andrew Wood, from a drug overdose.

The Screaming Trees had moved to Seattle to get serious. Back in Ellensburg, the band members barely hung out together, and rehearsals were hit and miss. Even Lanegan would admit that a move to the bigger city could get them motivated. Despite their protestations that they didn’t go there to become part of any scene, they would have been blind and deaf not to notice what was going on around them. It didn’t take long for major label Epic (future home of Pearl Jam) to sniff them out.

“Soundgarden were the only other band signed to a major when we got picked up,” says Van Conner. “I think Alice In Chains were getting their deal at about the same time as us.”

The first fruit of their major-label deal was their fifth album, Uncle Anesthesia, co-produced by Terry Date and Chris Cornell (whose then-wife, Susan Silver, managed the Trees) and released in January 1991. Easing back on the psychedelia, it brought them a minor hit in Bed Of Roses.

But while the rest of the world was being swept along by Seattle’s charms, they were finding the Screaming Trees easier to resist. The band didn’t help themselves. Lanegan was chronically backwards in coming forwards in interviews, and the burly Conner brothers were hardly typical MTV eye-candy. The band didn’t care how people saw them, and behaved accordingly. Tellingly, they cancelled the closing dates of the Uncle Anesthesia tour because they were too drunk to continue.

In 1992, as the band began work on their next album, Sweet Oblivion, Barrett Martin replaced original drummer Mark Pickerel. There was, Martin recalls, “a definite tension in the band, a fine balance between being creative and being destructive”. Fights in the studio were rare, and usually confined to the brothers, one of whom would usually end up sitting on the other. But outside the studio, things were getting increasingly dark, not least for Lanegan, who was simultaneously in the grip of heroin addiction and trying to record his second solo album (the first, The Winding Sheet, was released in 1990).

Despite all that, the band managed to produce one of the great records of the era. Majestic and dark, Sweet Oblivion represented grunge’s classic rock wing. It would go on to sell a quarter of a million copies, and the swirling Nearly Lost You even gave them a Top 50 UK hit.

For the first time in their career, the Screaming Trees were in the driving seat. But the wheels were about to fall off. Lanegan was up to his eyes in addiction, and alcohol had the best of the rest of the band. Stories abound of one band member cutting himself with a straight razor on the band’s bus, or stubbing out cigarettes on his forehead.

While the Screaming Trees were busy damaging themselves, bigger forces were sabotaging the band. In Autumn 1992, Epic insisted they support label-mates Alice In Chains. “We were meant to headline theatres around America and Europe, bigger rooms than those Alice were going to play, but Sony insisted that we open for them,” says Martin. “They threatened not to support our records if we didn’t do it; they acted like gangsters.”

The following summer they found themselves opening for MTV-friendly one-hit-wonders the Spin Doctors. “Us and the Spin Doctors,” says Martin, disbelievingly. “Playing support is not how to make a career out of a band.”

In the end, the Screaming Trees toured for two years on the back of Sweet Oblivion, and when they finally finished they found they were no further along than before. Worse, they were exhausted and trying to deal with their various problems. It was not a good time to work on a follow-up.

We were itching to go, but nobody’s energy was at the level it was when we did Sweet Oblivion,” says Martin. “We were trying to put our personal lives back together again.”

Things just wouldn’t spark, and initial sessions at the start of 1994 were scrapped. By their own admission, the songs they’d recorded simply weren’t strong enough. Some were ditched altogether; others, such as Dying Days, Black Bible, and Silver Tongue, would eventually make it on to subsequent records. “It was too soon,” said Lenegan. “None of us were ready to interact.”

In 1995 the Screaming Trees were finally corralled into a studio for several months with Black Crowes producer George Drakoulias. The usually combative band were worn down by the process of writing and recording, although ironically, the resulting album, Dust, was arguably their most consistent record. Fired by Lanegan’s world-weary growl, the likes of All I Know and the magnificently coloured Halo Of Ashes owed more to American blues and folk than to punk rock or psychedelia. Potent and stirring, it was a record out of time in every sense.

For the live shows, the band brought in Josh Homme – while he was still on the rebound from Kyuss – as second guitarist. Lanegan took to him instantly, claiming that the band tempered their behaviour accordingly: “We didn’t want to act up too badly in front of the kid.”

It wasn’t enough to keep the singer on the straight and narrow, and in the midst of touring Dust he was arrested for possession of crack and forced into rehab. He spent the next eight months in a drug treatment facility in Joshua Tree.

“Lanegan’s one of the greatest singers of my generation,” says Martin. “And in hindsight it’s better that the Trees missed that world tour, because everyone in the band is still around. If we had stayed on the road, that might not be the case.”

It was the winter of 1998 when the Screaming Trees went into Stone Gossard’s Studio Litho to record what would be their final album. Van Conner says that the band had parted company with Epic and were looking for another deal; Barrett Martin says they simply made the record for the hell of it. But they agree that the mood within the band couldn’t have been further away from the chaos and simmering animosity of Dust.

“We were just hanging out with no label, no tour, not much of anything really,” says the drummer. “I said: ‘Fuck the corporation and that bullshit, let’s just go in and record these songs while we’re still together in Seattle’.”

The band paid for the sessions themselves, with Martin producing. Despite the fact that the likes of Ash Grey Sunday and Revelator were as good as anything from Sweet Oblivion or Dust, the record failed to act as bait for the record companies. The labels hadn’t just lost interest in the Screaming Trees, they’d long ago lost interest in Seattle itself. The Trees had neither the energy nor inclination to carry on. When they played their final show, on June 2000, their final album remained unreleased.

A decade on, Van Conner was surprised when Barrett Martin mentioned putting the final Screaming Trees record out. The drummer had moved back to Seattle a few years earlier and had been thinking about the band’s legacy. He had done a rough mix of the album in 1999 and given all the members a copy on CD; Martin was the only one who had hung on to his. He dug out the tapes and took them to Jack Endino. The producer was blown away by the songs, and the pair decided to mix it properly and release it.

“I knew I’d have to get permission from the other guys, so I sent them my rough mix,” Martin recalls. “Even Lanegan was like: ‘Wow, these are really good. Put ’em out.’”

The album was finally released in 2011 as Last Words: The Final Recordings, via the drummer’s label, Sunyata Records. Even though Van Conner says it’s “for old-school Trees fans – I don’t know if the rank and file will care”, it’s easily good enough to sit alongside Dust and Sweet Oblivion.

Martin has played with countless outfits since the Trees split, including his own jazz rock ensemble the Barrett Martin Group, and Walking Papers with Guns N' Roses bassist Duff McKagan. Van Conner's band Valis released their most recent album Minds Through Space And Time in 2021, the same year Gary Lee Connor unveiled his most recent solo album, Revelations in Fuzz.

Mark Lanegan joined Queens Of The Stone Age after the Trees’ dissolution, released several highly acclaimed solo albums, and became an in-demand collaborator. When he died, on February 22, 2022, at the age of 57, he'd been clean for two decades.

“The Trees were an incredible band that rode the lightning,” Martin told us in 2011, “And Mark’s recovery, after all the shit that he and the rest of us had been through, was the greatest part of all: the triumph of the spirit."

The original version of this article originally appeared in Classic Rock #167, in February 2012

- RELATED READING: The tragic story of Mad Season