Growing up in the mid-60s in Cannock in the West Midlands, Glenn Hughes had three heroes. The first two were those of many other kids: George Harrison and Eric Clapton. The third was a teenage guitarist three years ahead of Hughes at school, name of Mel Galley.

It was Galley’s example that convinced Hughes to ditch trombone lessons and pick up the guitar. And when at 17 he was offered the chance to join Galley in a local covers band, Finders Keepers, he leapt at it, switching to bass guitar so as to be able to fill the vacant role. The band enjoyed a measure of success on the Midlands club circuit. But as the 60s came to a close, audiences looked for things more original and challenging.

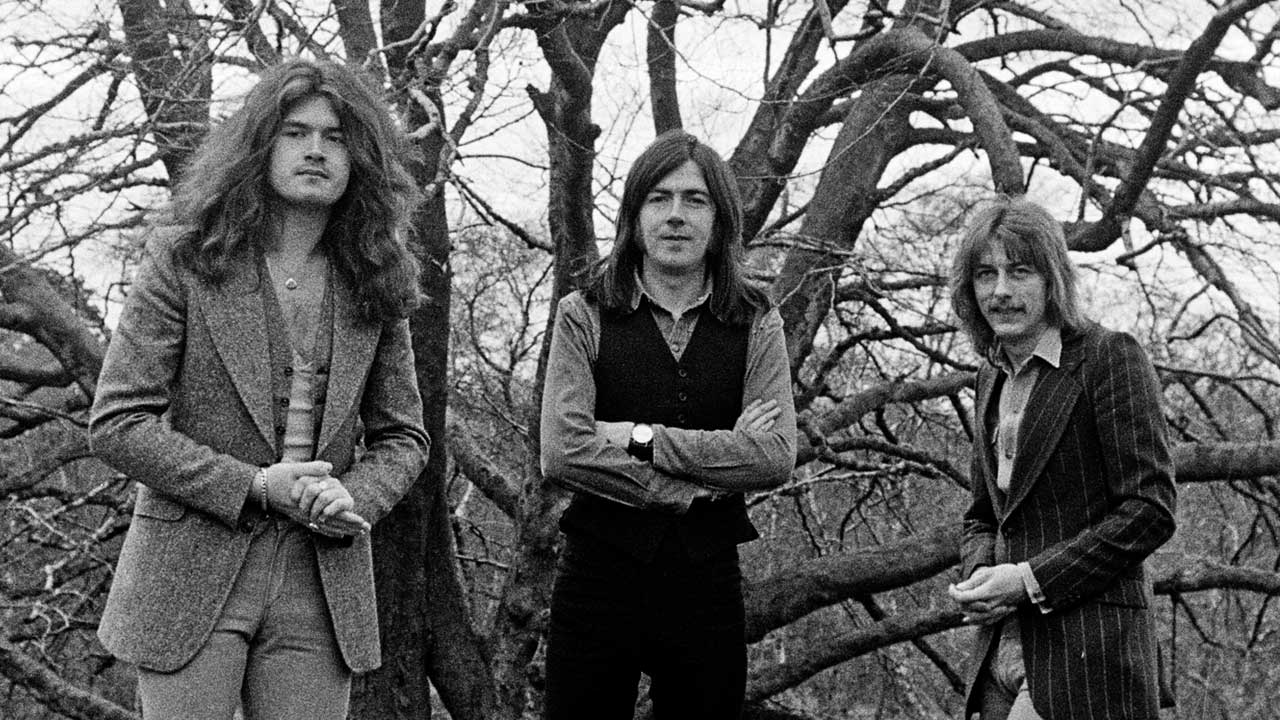

In 1969 their enterprising manager, Tony Perry, decided to take away Hughes, Galley and drummer Dave Holland, and pair them with a couple of older hands from another covers band he looked after, The Montanas. Teaming up with singer/trumpet player John Jones and keyboard player Terry Rowley, they became Trapeze.

One of the first songs the new group wrote, a decorative ballad by Rowley titled Send Me No More Letters, attracted the attention of two of The Beatles’ chief lieutenants, Neil Aspinall, head of the Fab Four’s Apple Corps, and their one-time roadie and now personal assistant Mal Evans.

“Neil and Mal came down to see us play a couple of early shows in London and wanted us to record for Apple,” Hughes recalls. “We even went down to the Apple studio at 3 Savile Row. They had just had this new sound board flown over from America, but the engineers were so stoned on pot they couldn’t figure how to operate it. We were surrounded by greatness, all these drums and guitars that The Beatles had used, but no one was capable of recording us. After two days of hanging around the place we just left.”

Instead, Trapeze threw in their lot with a band closer to home, the Moody Blues, from Birmingham, signing to their Threshold Records. Moodies bassist John Lodge produced Trapeze’s self-titled album, which was very much a period piece with its surfeit of whimsical psychedelia and flowery harmonies. By then, Perry had concluded that Hughes was a better bet as lead singer than the more experienced Jones, so it was the fresh-faced teenager who fronted the record.

“Six months after the band had released that first album, people were apparently talking about me as a great singer, but I’d had no inclination of that,” Hughes insists. “I hadn’t even known I could sing. The only other bass player fronting a band back then was Jack Bruce [with Cream]. Our situation just came about through circumstance, but for me it was like: ‘Everyone! I have arrived!’”

Soon enough, the displaced Jones and also Rowley returned to the more familiar confines of The Montanas. Freed up, Hughes, Galley and Holland set about transforming themselves into a power trio, following a blueprint laid down by the likes of Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

The band’s second album, Medusa, released in November 1970, just five months after Trapeze, was altogether more forceful. Its seven songs were revved along by Galley’s chunky riffs, but they were particularly marked out by Hughes’s voice. Speaking today, Hughes still bursts with enthusiasm at the mere mention of Medusa.

“It’s a beautiful piece of music,” he lavishes. “I was still getting used to coming out of a band that was four-part-harmony-based and my voice was a little thinner then, but I was very influenced by Steve Marriott and the great soul-rock singers. When you cross rock and soul, that’s what Glenn Hughes is all about. I wrote the closing title track in two parts. The intro is very melodic and American West Coast-sounding, and the second part riffy and heavy. Ever since, I’ve carried that kind of crossover with me.

“Even before Medusa had come out, the Moody Blues took us out on tour with them in America. We did seventeen shows in twenty days, playing to fifteen to twenty thousand people a night. By the time we got to Texas in December 1970, they took to us like we were Texans. That’s when the rocket ship lifted off.”

Trapeze criss-crossed the US four times in support of Medusa. Although the record didn’t break through nationwide, they built up pockets of hard-core support on both coasts and in the south. Not surprisingly, when it came time to make their third album, a strong American influence found its way into the new material that Galley and particularly Hughes were writing.

Altogether, 1972’s You Are the Music… We’re Just The Band was an airier, more melodic and varied collection than its predecessor, and on its two standout tracks, Coast To Coast and What Is A Woman’s Role, Hughes gave full rein to his soulful, acoustic-based side.

“I was an avid vinyl collector of all kinds of music,” he explains, “and at that time Crosby, Stills And Nash, Stevie Wonder and Sly And The Family Stone were all going through my head. For me, it’s a very progressive sounding record and entirely different to Medusa. I was still just nineteen, twenty and growing as a songwriter.”

Almost immediately, You Are the Music… caught the ears of Ritchie Blackmore. At the time, Blackmore was at loggerheads with Ian Gillan in Deep Purple and also contemplating ousting Roger Glover, so was already scouting for replacements.

When, in the autumn of 1972, Trapeze played a four-night stand at the Whiskey A Go Go in LA, Blackmore was in the audience on the first night, Jon Lord and Ian Paice on the second. It was the beginning of a courtship that would last nine months, concluding in May 1973 when Purple’s mainstays had Hughes flown from Baltimore to New York City to see Purple play at Madison Square Garden.

“They asked me there and then if I’d like to play bass in their band,” he recalls. “I replied: ‘Um… but I’m a singer.’ To which they told me that I would sing as well, but that they were going to ask Paul Rodgers to be their lead vocalist. At that, I said: ‘I’m in! Where do I sign?’”

Of course, things didn’t quite play out that way. Already in the process of putting Bad Company together, Rodgers declined the offer, and Purple instead picked out the young, unknown David Coverdale to complete the new line-up that soon rattled off the Burn and Stormbringer albums.

With Hughes gone, Galley took over on lead vocals in a reconfigured Trapeze. A fourth album, the so-so Hot Wire, scraped the lower reaches of the US Billboard Hot 200 in 1974.

Hughes’s Purple adventure took off in front of 400,000 people at the California Jam in April 1974, but it wasn’t long before it turned sour. By the time a Blackmore-less Purple ground to a halt in March 1976, he was bingeing on booze and cocaine, a mess. He retreated to the Black Country, and started work on a first solo album, 1977’s Play Me Out, with Galley and Holland joining him.

“I began making that record in the long, hot British summer of 1976,” says Hughes. “To all intents, it was Trapeze back together. It was going so well I called my agent in America and told him I would love to take Trapeze out to the States that August.”

The good vibes lasted for just as long as it took for the re-formed Trapeze to rehearse for the tour and hit the road. Hughes had split with his longterm girlfriend and taken up with Exorcist starlet Linda Blair, who was also on a self-destructive streak. They were disastrous as a couple, and the ailing Hughes quickly bailed from the tour.

“It was a difficult time for me,” he says now. “I wasn’t in the greatest head space and was doing what I was doing. You know the story. Let’s just say I was over-serviced at the bar. It was the wrong time for me to do a tour."

Galley went on to join David Coverdale’s Whitesnake for a spell, Holland joined Judas Priest, and Hughes eventually won the battle with his demons. Eighteen years later, Trapeze tried again and managed 20 dates around their traditional American strongholds. The stars were no better aligned, though, for it to amount to more than just another fleeting reunion.

“The shows were great, but I was a sober man now and other people weren’t,” says Hughes. “I love my friends, but I couldn’t be around people who got shit-faced all the time.”

An occasional one-off get-together aside, those 1994 shows were Trapeze’s last. Their legacy should be the six studio albums they ultimately made. Yet in 2004, a darker, more harrowing chapter was written into their story. Holland was convicted of the indecent assault of a 17-year-old lad with learning difficulties who he had been teaching drums to. He served eight years in prison, and continued to protest his innocence up to his death in January 2018. Galley died in 2008, taken by cancer at 60. Hughes, enjoying a career renaissance in what can be considered his twilight years, even now refers to Trapeze as “my band”.

“At one time, you couldn’t have put bets on me being the only one left,” he says wistfully. “We were just kids in Trapeze, and obviously there was all that stuff with Dave that happened afterwards, and that I wasn’t privy to. But the memories of that band are ones that will stay with me forever."

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 249, in June 2018.