The story of Ugly Kid Joe

Uglier than they used to be, but still rad to the bone...

Ugly Kid Joe arrived on the scene just weeks after Nirvana released their 1991 album ‘Nevermind’.

Hailing from the Californian coastal town of Isla Vista, the quintet – vocalist Whitfield Crane, guitarists Klaus Eichstadt and Dave Fortman, bassist Cordell Crockett, and drummer Mark Davis – were arguably the last band from the glam metal era to make it through the gate. After that, grunge hit the reset button on guitar music and presented many of the biggest bands from the ‘80s with one of two options: redefine themselves or become irrelevant overnight.

But Ugly Kid Joe weren’t your average West Coast band. Sure, there were elements of cock rock in their music, but they took in a range of styles: hard rock, southern rock, metal and lashings of funk inspired by the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Faith No More. But what really set them apart was their fondness for parody and their unruly sense of humour. The band’s very name poked fun at Hollywood’s Pretty Boy Floyd, while their album titles would consistently lampoon contemporary releases from the worlds of both rock and hip-hop, music and movies. Nothing was off limits.

Thanks to the massive success of the band’s debut single Everything About You, their 1991 debut EP As Ugly as They Wanna Be (a parody of 2 Live Crew’s 1989 album As Nasty as They Wanna Be) became the first short-form LP to be certified platinum, and it remains the highest selling debut EP by any band to date. They promoted the record in the US during a tour with their heroes Ozzy Osbourne and Motörhead, and signed with Mercury the following year. 1992 saw the release of their full-length debut, America’s Least Wanted (a parody of Ice Cube’s more serious AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted). The album, which featured vocals from Rob Halford [Goddamn Devil], soon went double platinum and spawned their second Top Ten hit – a cover of Harry Chapin’s Cat’s In The Cradle.

Before recording their second album Menace To Sobriety in 1995 with producer GGGarth Richardson, the band recruited drummer Shannon Larkin. They scored support slots on Van Halen and Bon Jovi’s US arena tours and for a while, could do no wrong. But the music landscape was changing, and the pitfalls of success, substance abuse, and relentless touring were slowly catching up to them.

They parted with Mercury Records later that year, releasing their third and final album Motel California independently in 1996, before officially disbanding a year later. The five members spent the next decade playing in various other metal bands – from Godsmack and Amen to Life Of Agony – before rumours of a reunion began to surface five years ago.

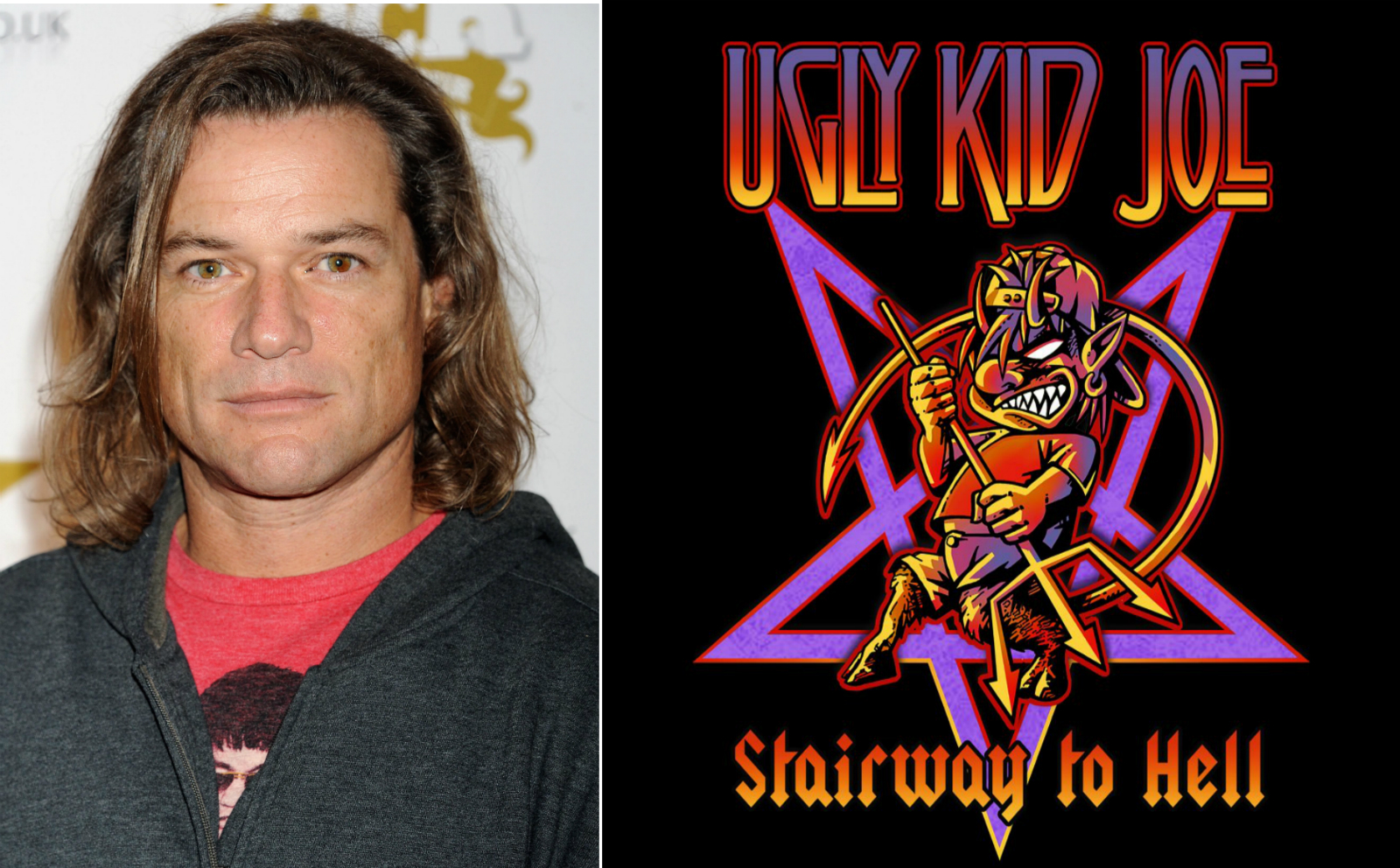

By 2010, the band had reunited and recording sessions soon followed. The EP Stairway to Hell was released in the summer of 2012, which also marked the band’s return to Europe for the first time since 1996. They played two UK sets, first at the Underworld in London, before taking to the second stage at Download Festival.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

They joined Alice Cooper on his Halloween Night of Fear tour in the Autumn of 2012, before returning to the UK last year for a co-headline tour with Skid Row. And this summer, the band released Uglier Than They Used Ta Be – their first full-length album in 19 years. To mark the occasion, the quintet enlisted the help of Phil Campbell from Motörhead, who lends his signature guitar sound to UKJ’s cover of Ace Of Spades.

We joined Whit in Manchester during the band’s current UK tour to learn of the improbable rise, fall and resurgence of one of the ‘90s biggest-selling bands…

When Ugly Kid Joe formed back in 1991, where did the band fit in with what was happening in music at that time?

Whit Crane: “When we came in, it was all the cock rock stuff. The model was that you had two big singles, then your third single was a love ballad, then you sold three million records. That’s what you did. Every song had a particular formula, and everyone had big hair. We were from California, loved the [Red Hot] Chili Peppers and Mötley Crüe. That was our amalgamation. Van Halen and [Black] Sabbath, and all those other elements were in us, and we loved funk, too. But we weren’t really that good at it. I’d never seen a band like the Chili Peppers before. And I’d never seen a band express themselves like that. My bands were – and they still are – Judas Priest, AC/DC, Sabbath and Van Halen. But I’d never seen anything like Anthony Kiedis or Flea. Flea’s kind of like Angus Young, in the sense of like, ‘Oh my God!’ They just blew my mind. We were living in Isla Vista at the time, and we weren’t planning on getting a record deal or anything like that. We were planning on getting on the local radio show. That was our goal. It was my dream to hear myself on the radio. Of course, I achieved that. And when we made that first demo it was good enough for people to be interested in it, and the whole thing started rolling from there. We could draw like 800 people to our hometown shows, and all of a sudden, there was a big buzz around the band. The songs that I just wanted to be on the local radio station were now being sent to record labels. Then there was a bidding war over us and then we had a record deal. But where did we fit in? We’ve never really fitted in. Where could you really place us? Who are our contemporaries? We have our heroes and our leaders. We have our Godfathers, like Ozzy and Lemmy. Those guys have always given us love and taken us on tour. But in a peer group, who’s right next to us? There aren’t any bands that I can think of. And that was a lonely process because when we blew up there were no bands of our era that we could tour with. I don’t know if we fit in anywhere.”

What do you remember about playing huge arena shows for the first time?

“Funnily enough, I actually found myself in my natural setting. You don’t know that until you get there, obviously. At first you think, ‘Oh shit! That’s a big crowd. I wonder if I can pull it.’ And then you get into the eye of the storm, and for me, it was instantaneous. Of course, I watched what the masters like Ozzy and David Lee Roth would do, and I took that and turned it into my own thing. That’s just life in general. But it was a natural thing, and it came real fast to me. And I loved it. I still love it.”

What was it like making America’s Least Wanted?

“I didn’t like being in the studio – at all. From an experiential vantage, application and reality, I was a live guy. I still am. Everything we’re doing, including this interview, ends up on the stage. We’re throwing wood on the fire to go and play live. Making a record, shooting a video, or doing an interview – whatever it may be – all leads to the live show for me. Back then, we got our record deal and all of a sudden we were in the studio with this big time producer named Mark Dodson [Anthrax, Suicidal Tendencies]. And back then, I really could sing better live. The studio is formulaic and weird to me. It’s all-important and scary, and I wasn’t comfortable in there at all. I didn’t like it, and I didn’t understand it. I still have a very short attention span, but back then it was even worse. So I was a total pain in the ass, based purely on my fear of the recording studio. Luckily I had some very patient people around me, including my band and our producer, and ultimately we had fun making a great record, which was America’s Least Wanted [1992]. It was a cool, funny, drunk experience.”

What did Mark Dodson bring to the table?

“Well, we’d just come off the EP [As Ugly as They Wanna Be, 1991], which sold a lot of units – or records, or CDs, or whatever you want to call – and we were looking at producers. When you sell a million records, you can pretty much work with anyone you want, and we were looking at the discography of who had done what. That’s when we found Mark Dodson. He’d worked as an engineer on Sin After Sin [1977] by Judas Priest, and he also worked on Defenders of the Faith [1984]. So I said, ‘Let’s get the Priest guy’, because in case you didn’t know it, I’m a massive Judas Priest fan. I didn’t even listen to anything else that he’d produced. He’d worked with Priest, and as far as I was concerned he was in. If you’re going to compare sounds, it’s Mark Dodson, which means Infectious Grooves, Suicidal Tendencies, Judas Priest and Anthrax. And you know what Mark is particularly great at? Guitar sounds! So the guitar sounds on America’s Least Wanted are fucking humongous, awesome. But my methodology was just blindly committing to a guy who had worked with Priest, which is not intelligent at all. Thankfully, in this case, it paid off.”

Did the addition of drummer Shannon Larkin influence the sound of the second album, Menace To Sobriety?

“The Shannon Larkin story itself is crazy. You could do a whole interview just on how I met him and the impossibility of that. But let’s just say that Shannon Larkin was a great sign, and I’m forever grateful that he showed himself to us. When I think of Shannon, I think of his incredible skill set, his magic, as a human being and a spirit. And if you’ve ever seen him play drums, you’ll know that he’s just insane. In my mind, we joined Shannon. I say that to him to this day. He’s the fucking shit! And when he came into the fold he brought the best out of everybody because you had to keep up with him. He took us to a whole other level. And you put that dude next to a bass player like Cordell Crockett, we had the rhythm section from hell. We wanted to make a heavier record, so all these elements were at play. We went into the studio pretty polluted, and the Menace to Sobriety [1995] title was very apt, but it was still a fun experience. We made another great record, which was followed by one of our favourite tours ever with Van Halen and Bon Jovi. That was a great time!”

**Why did the band part ways with Mercury Records in 1995?

**“Going back to labels and all those people, I wish I could connect with everybody. I’m pretty idealistic like that. And stupid in a lot of senses, because I just want the world to be like I want it, and it’s not. I could sense that the label weren’t backing us on Menace to Sobriety. They weren’t not backing us. And they would’ve let us make another record, and we could’ve done that, but it just didn’t feel right. I pulled my manager to the side and I told him we wanted off the label. He told me he didn’t think it was a good move, but I wanted off the label because I believed we could find another one and be who we are, so we walked away. In hindsight I don’t know if that was the right move, but I felt it so thoroughly at the time because I couldn’t connect with the label, and back then I was just a purist. I couldn’t separate the businessman and the frontman, and I just wanted out. So we got out. And then we went and made Motel California with Castle Communications, which actually was a fantastic deal. We got a great advance, and we had a great amount of money per record given to us. So it wasn’t necessarily a bad thing to get off Mercury, and either way it would’ve been over anyway, because nobody really wanted it anymore. Not really.”

Why did the band split so soon after?

“I think it was an amalgamation of many things. I think we were all sick of each other. I was sick of them. They were sick of me. You’d have to ask each guy. But after our last gig in Austria somewhere, in December ’96, I went to India. I went and got an Enfield motorcycle and started fucking around in Goa. I used a crazy phone off the side of a rice paddy and called everyone telling them they needed to get out to India because I had a fucking mansion and it was badass. I called Klaus [Eichstadt] and he was all, ‘I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to come to India. And I don’t want to be in the band anymore.’ They had all decided that they didn’t want to be in the band anymore, and I was like, ‘Wow! OK.’ And that was it. Nothing ends well, really. I can’t really think of any marriages or relationships that end well. But I suppose the band ended at the best time that it could. We weren’t mad at each other, and nothing evil or horrible happened. We just ended it. But it still was really sad, you know.”

So what led to the reunion almost a decade later?

“Well, I thought it was over for good. Every time I asked Klaus [about reforming] he just said, ‘Nope. Nope.’ And that’s fair. But the interesting back-story with me and Klaus, is that we’re best friends from childhood. So when the band ended, we just went right back to being friends. We grew up together. So that was fine. With the other guys, our relationship was based on creativity. When we’re creating, we’re connected. After the band broke up I would still see everybody, but it was a little uncomfortable because we were no longer in a band together, so who were we? We still had a common denominator of experience, but we were no longer living that experience so it became like this weird shadow. That true connection wasn’t there because we weren’t doing what we were born to do together on earth, which was create. Anyway, I guess Shannon and Dave Fortman were making a record together. The computer was there, and all the in-house skill sets were apparent and obvious. And I guess they figured we could go make an Ugly Kid Joe record by ourselves. So it came from Shannon and Dave to Klaus, and then to me. And I think it had to come that way in order for it to actually happen. They asked me if I was up for it and I was like, ‘Dude, I would’ve done it five years ago. Fuck it! Let’s do this.’”

You released the Stairway to Hell EP in 2012…

“Funnily enough, we recorded half of it in LA with Sonny Mayo [Sevendust, Snot] as the engineer, and half of it in the swamp with Dave Fortman. I hadn’t connected with Sonny Mayo yet, and Sonny did not get me. I said to him one day, ‘You better start learning these songs, because you’re going to be in the band.’ And then there he was. So it all kind of came together. And beyond the new music and the touring, we’re all connecting again. It’s a rare moment in time and space to get to experience all the things that we did in the first place, and like with so many bands, it all came to an end. After that, there’s nowhere to apply all the wisdom that you’ve learned and it’s maddening. But the desert was equally important, because hunger is the best spice. And sure, it’s taken 15 fucking years, but now we’re here and everyone’s back together. And we made this new record. And it’s electric, and healing, and joyful, and complete. And we all love each other. And we have this new drummer in the band: Zac Morris. He’s a kid, and he crushes it, and he’s ready to learn from us. So a lot of good stuff is going on right now. I’m over the moon about the present.”

When the band started, you were all in your 20s. You’re now all over 40. Can Ugly Kid Joe still be that same rebellious rock band that it was back in 1991?

“Well, you are what you are, when you are. It’s an interesting question, because I think of it in tones. And when I say tones, I’m referring to myself as a vocalist. If you listen to the tone of my vocals on As Ugly as The Wanna Be, and then the tones on America’s Least Wanted and the pocket I’m singing in there, and you follow the whole thing all the way through to the new record – then you can see where I’m at. The tones tell the stories to me: the full tone, the thin tone, the scared tone, the big tone, and the raspy tone. And in that, you can hear my evolution. So we’re not the same band, no. We’re an amalgamation of shifting parts, and with this record we got to come home. There’s a special sheen and sparkle to that. Everyone is here from the heart, and so it sounds like it’s come full circle. As far as lyrical content goes, I’m an optimistic cynic and a host of contradictions. The same element of rebellion that was there in the early days is still there, but that’s just one of the descriptions of our band. It would be a limiting to just use that one definition.”

How would you describe Uglier Than They Used Ta Be to long-time fans of Ugly Kid Joe then?

“It came about because we wanted to make music together. If you’re chasing something, or running away from something, it’s not going to sound good. We’re making music for us, because we love each other and because all the things that I’ve talked about exist right now, and they should be celebrated. Of course, the fans financed it first person too, and that’s fantastic. But it’s an honest record, man. I don’t know what to tell you other than that. I can tell you this, if I like it then they’ll probably like it. And I like it…”

Tell us about the Phil Campbell connection.

“Our Welsh connection! He’s fucking amazing. Of course, our first big tour with Ugly Kid Joe was with Ozzy Osbourne and Motörhead. We went from the mean streets of California to playing 17-22,000 venues all over America, sharing the stage with fucking Motörhead and Ozzy Osbourne on his No More Tours Tour in 1992. We connected with those guys [Motörhead], and their whole crew has always looked out for us. I’ve kept in contact with them over the years, and Lemmy sang on a song on Motel California [Little Red Man]. They’re our friends, and they’ve always looked after me. It’s a strange little thing that I don’t even want to question or talk about too much, but they’ve always been really kind to me. So we’re making this new record, and we’re in the studio and I have a thousand ideas – all day long, it goes on, and on, and on. And I said to the band one day, ‘What if we got Phil Campbell on this song, and we could do this and that, and it would be great.’ And they were all like, ‘Yeah sure, whatever.’ I really wanted to cover a Motörhead song for the album, but nobody would listen to me because they all wanted to do the original stuff. But I was adamant on doing Ace Of Spades. And at the last minute Zac goes, ‘Hey boss, I’ve got this.’ He walked in the drum room, told whoever was at the helm at the recording desk to press record, and he proceeded to track Ace Of Spades with no band – no click track, no guitars, no singer, no nothing. So that’s the first part of the story: the impossible drummer that played with no band – that’s crazy shit in itself. We then track the rest of the song, and we’re all like, ‘Holy shit, this is amazing!’ Then all of a sudden my phone rings and it’s fucking Phil Campbell calling me to see how it’s all going, because we check in on each other. I told him what we’d done and asked him if he’d like to play on the record, and he said, ‘Absolutely, I’d love to.’ Ace Of Spades is obviously not that exciting for Phil Campbell, you know? So he said, ‘If I do that song, then I want to play on some of your songs.’ He was on tour in Europe, kicking ass with Motörhead, and he took a couple of days off to jump in his son’s studio in Wales and record some parts. We sent him three songs – My Old Man, Under the Bottom and Ace Of Spades – in the hope that he could get to do it. And he really did it.”

So he ended up playing on three songs on the new album?

“Yep. You have Ace Of Spades where he rips a solo, My Old Man where he plays the first solo that shows itself and Klaus plays the outro, and he shreds in the middle of Under The Bottom too, which I think is the greatest, heaviest song that Ugly Kid Joe has ever written. It’s incredible. If you’re going to jam with somebody that you admire and love, you really want it to be a good or even a great song. And it’s not always that. But this is that. So the track to look for on this record, Uglier Than They Used Ta Be by Ugly Kid Joe, is Under the Bottom, featuring Phil Campbell from Motörhead ripping your face off.”

What does the future hold for Ugly Kid Joe?

“I don’t know, man. I think there’s more of a strategy in place this time around, and we want to get this record out there, which will hopefully be celebrated. We want to make the fire a little brighter. Then we want to pick up some killer tours. And the eye on the prize is a kick ass summer run, festival style, with this exact crew and everybody that’s on this bus. Everybody from the tour manager to the soundman is kicking fucking ass right now, and it’s great to be around. It’s like a family. But the main goal is to enjoy life through music. And as far as where I want this record to take us, I just want to share it with the world and play big fucking rad rock shows.”

Ugly Kid Joe are on tour now. For more information, visit their Facebook page.

DJ, presenter, writer, photographer and podcaster Matt Stocks was a presenter on Kerrang! Radio before a year’s stint on the breakfast show at Team Rock Radio, where he also hosted a punk show and a talk show called Soundtrack Apocalypse. He then moved over to television, presenting on the Sony-owned UK channel Scuzz TV for three years, whilst writing regular features and reviews for Metal Hammer and Classic Rock magazine. He also wrote, produced and directed a feature-length documentary on Australian hard rock band Airbourne called It’s All For Rock ‘N’ Roll, and in 2017 launched his own podcast: Life in the Stocks. His first book, also called Life In The Stocks, was published in 2020. A second volume was published in April 2022.