Six months into the endless, ever-expanding time frame that was the making of Foreigner’s fourth album, producer Robert John ‘Mutt’ Lange decided he needed a break.

Looking up from the mixing desk in Electric Lady Studio, located at 52 West 8th Street in New York’s Greenwich Village, he yelled at those in the control room who, like he, had just endured yet another gruelling night-shift and missed yet another sunrise.

“What the fuck are we doing here? We need to go out! We never go out! We need to go to Central Park… Let’s go buy some Frisbees!”

With the band having long left the studio, ‘Mutt’’s outburst would only have been witnessed by his close coterie of engineering staff, and a young, then-unknown keyboard player named Thomas Dolby who had recently been drafted in for the sessions. All of them were startled, but took their cue and followed ‘Mutt’ up the stairs and out on to West 8th Street, blinking in the morning sunshine. He hailed a yellow cab and ordered it to wait outside 5th Avenue’s legendary toy store FAO Schwarz while he bought a variety of Frisbees, then leapt back in the cab and instructed the driver to take them all, giggling, to Central Park. For what Dolby remembers as a truly joyous five minutes, they raced about the park, flinging the coloured plastic discs around like excited schoolchildren high on life. But, after those five minutes, the real ‘Mutt’ Lange resurfaced…

“What the fuck are we doing here? We’ve got an album to make!”

With that, he led them all away, hailed another yellow cab and raced back to Electric Lady.

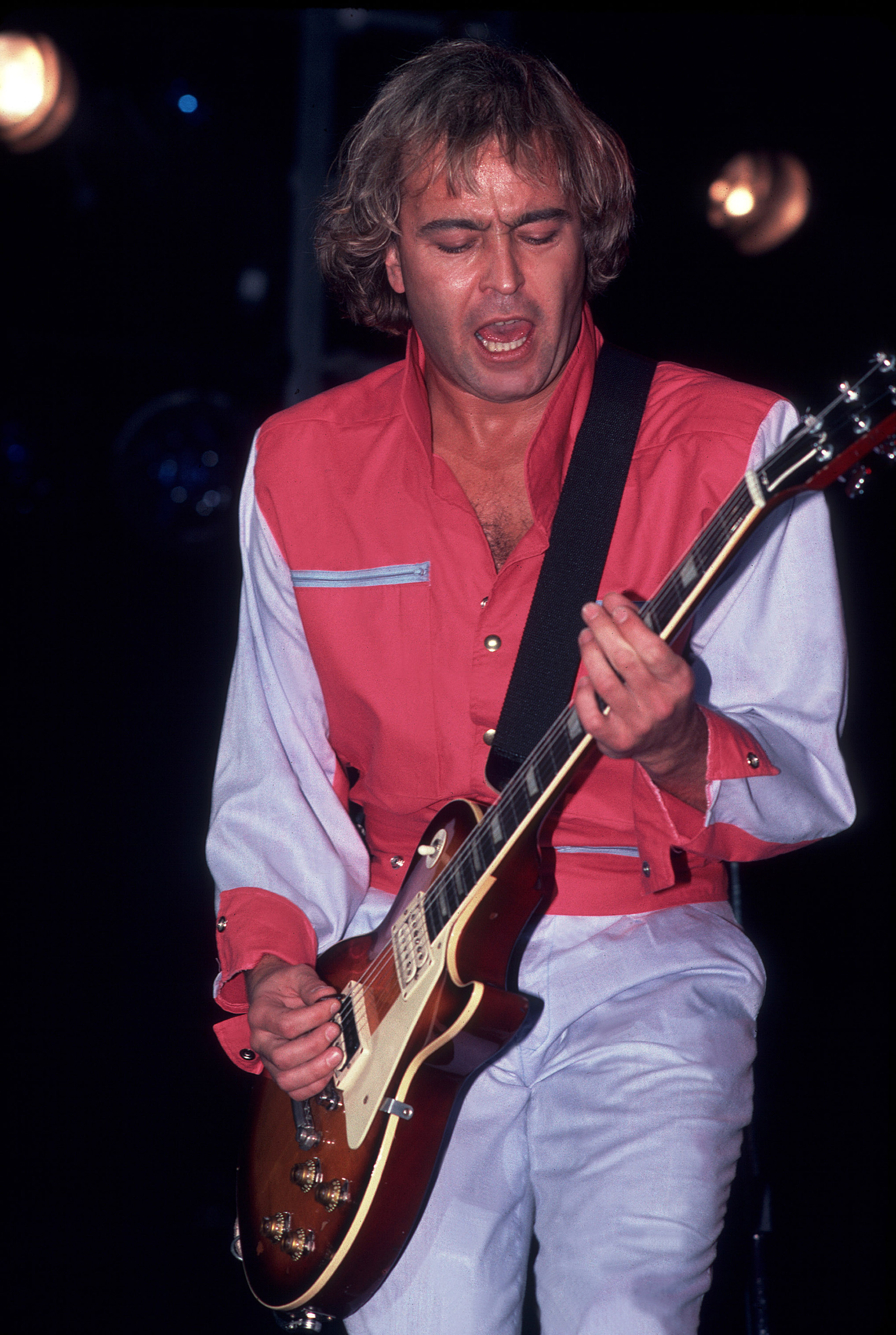

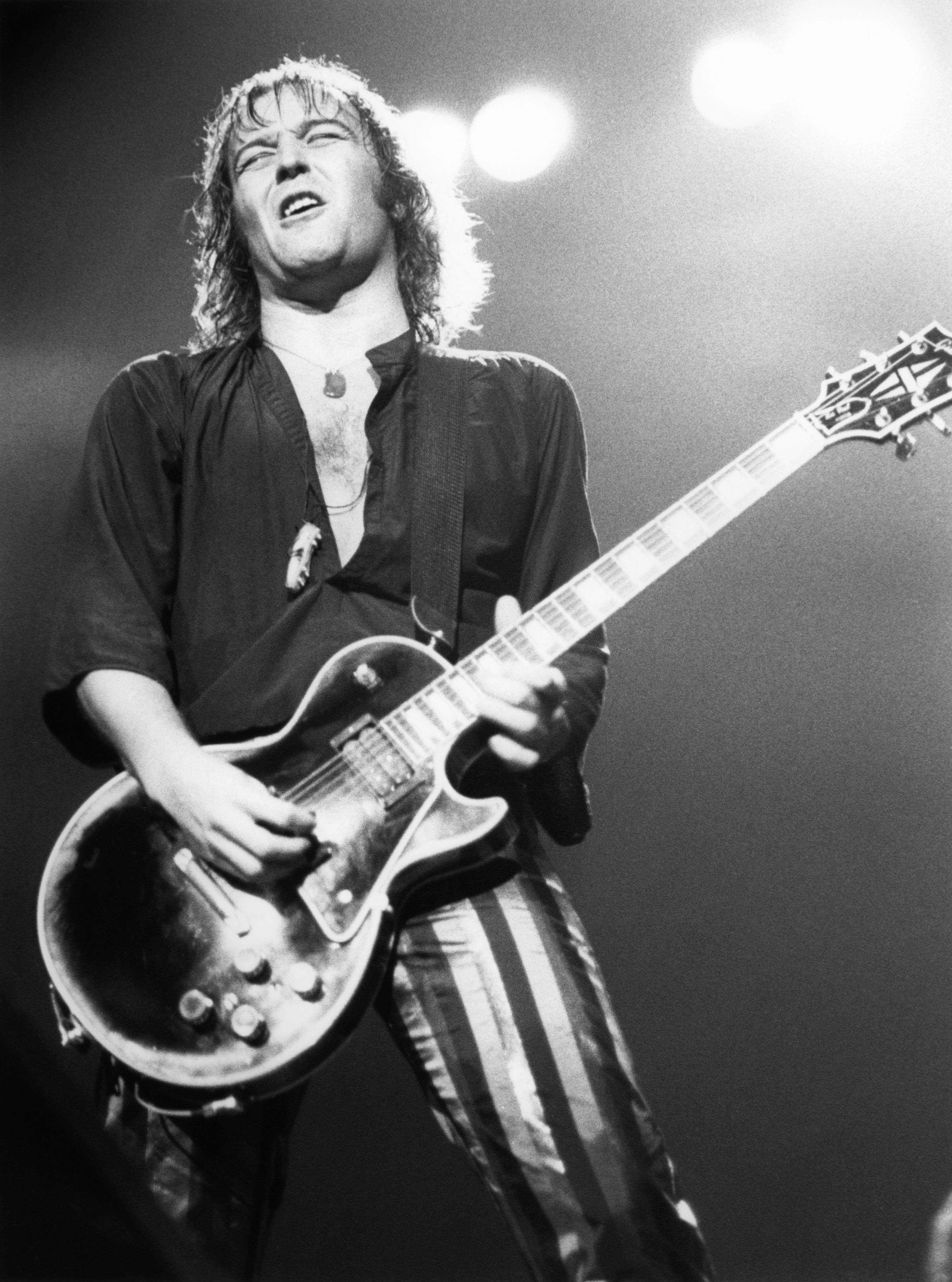

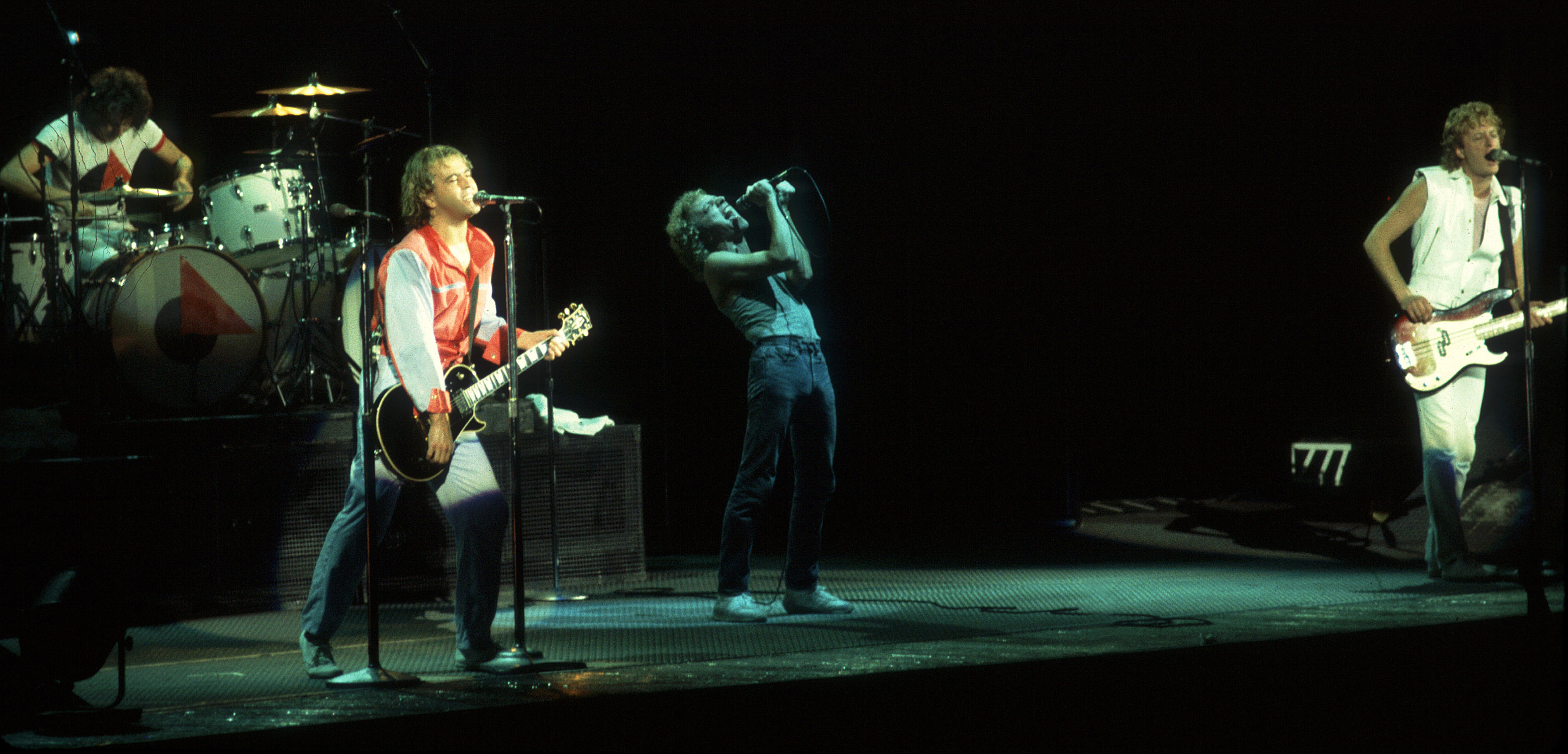

Foreigner’s guitarist Mick Jones hears this story for the first time when Classic Rock Presents AOR meets him in his London hotel suite during the band’s recent European tour. He might be unfamiliar with this specific tale, but recognises it immediately as indicative of what he describes as the producer’s “intense” commitment to the work. Jones recognises it, of course, because it mirrors his own, and explains why the album took so very long to make. How long?

“It took about 10 months, counting pre-production… maybe the best part of a year,” Jones shrugs, pointing out that the group’s 1977 debut LP had taken nine months, their second, 1978’s Double Vision “about six months”, and their third, 1979’s Head Games, “probably almost the same again”. So Foreigner had form in that department. But 10 months? The best part of a year. Wasn’t that some kind of record at the time? Apparently so…

“I remember I was in a club in London and Simon Le Bon came up to me and said, ‘I hear we’re in the running for the prize for spending the most time and money in a studio!’,” grins Jones, not a little ashamed as well. “Unfortunately, we did share that distinction…”

The Frisbee excursion was not a significant factor, then, in Foreigner 4’s extended gestation The real reason was Jones and Lange’s 100 per cent commitment to making absolutely the best record possible, and refusing to stop until they were sure they had. For both men, that meant achieving a new level of excellence in the songs.

Jones: “The songs are the basis of everything. They always were with this band. I always set out to make albums that you could listen to from beginning to end, without filler…”

The statistics for Foreigner 4 prove that all the hours, days, weeks and months in the studio, all the deadlines missed, all the budgets broken, were ultimately worth it.

The album enjoyed 10 weeks (in three spells) at No.1 in the Billboard charts, starting on August 22, 1981 and ending February 11, 1982. American sales exceeded six million. It remains the band’s best seller in the UK, reaching No.5, and earning a gold disc, while it also made No.4 in Germany. Of the six songs released as singles in the US, only the last - Luanne, in 1982 – failed to go Top 30.

Perhaps most importantly of all, 30 years later all 10 of these songs still resonate strongly.

So time and money are relative. As is failure.

A bit of context is needed. Foreigner were a success right out of the box: Stateside, their self-titled debut of 1977 sold five million copies and reached No.4. A year later, their second effort, Double Vision, made No.3 in the US – even climbing to No.32 in the UK – and shifted seven million copies. So when third album Head Games, released in 1979, stalled at No.5 on the Billboard chart and only went quintuple platinum, something was deemed to have gone wrong.

Jones: “That did start the thinking, that we needed to be positive about our identity for the fourth album. Okay, we’d beaten the jinx of the first album being a flash-in-the-pan with Double Vision being so strong, but I think on Head Games we really went into ‘excessive mode’. The drugs came into the picture a bit too much there. So we kind of had a massive hangover after that album [laughs]. I look back on it and think it wasn’t quite focused. We tried to toughen the image of the band up with Dirty White Boy and Head Games itself, but that’s where the question about where we were going originated…”

English bassist Rick Wills – who had joined the line-up for Head Games, the former Peter Frampton band/Roxy Music member having replaced New Yorker Ed Galgliardi – had a few concerns. “In some ways, after the first two Foreigner albums, Head Games was something of a departure in style and form,” he says. “It was a bit more heavy and rocky, and that didn’t go down so great with everyone. And, of course, we had that very controversial album cover…”

It featured a girl caught in the act of wiping her phone number off a gents’ toilet wall, but it was perceived by some as something more provocative. A lot of American record stores refused to rack it.

“I think we sold a lot less of that album for that reason alone,” Wills continues. “It did very well, but by Foreigner standards it was considered something of a failure. Having just come into the band I was thinking, ‘Bloody hell – this doesn’t bode well for my future!’”

Jones was thinking about the future, too, but Wills wasn’t the one who needed to worry. The guitarist and band-leader was more concerned that the demands of keyboard player Al Greenwood and ex-King Crimson multi-instrumentalist Ian McDonald to be included in the songwriting process would weaken the band. Greenwood was dismissed first, McDonald followed soon after (years later, when the band reconvened in mid-2010 to rehearse some new songs, McDonald was present, but the line-up was soon pared back down to four).

Wills: “I hadn’t expected this. Mick had said to me he wanted more freedom to bring other musicians in, to experiment – especially with keyboards – because this was the era when people were beginning to do amazing things, electronically. Mick – who was never one to stand still – wanted to try these things out, because he thought that was the way forward.”

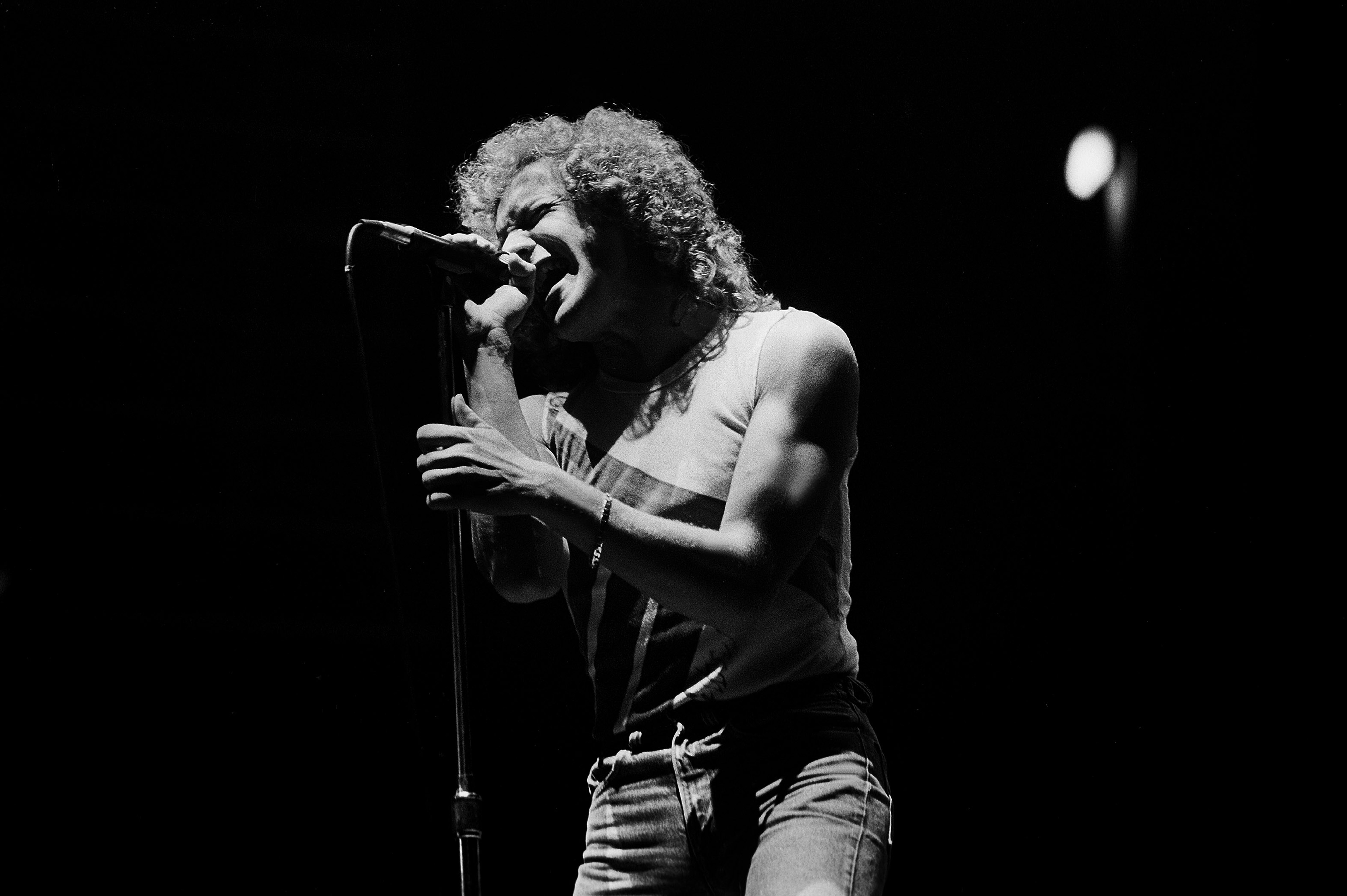

Jones: “It was a tough time, emotionally. Ian was a close friend, but Lou [Gramm, singer] and I just felt we had hit our stride writing together and we wanted to really start to maximise on that. We talked at length about it and had a fairly clear vision of where we wanted to go, so it was a question of being a bit ruthless. We felt we wanted to focus.”

One of the songs that was helping them focus was a ballad.

Wills: “Mick tended to write most of the songs on a piano, using mostly the black notes, so everything was in sharps and flats, and little bit weird when it came time to transpose them to the guitar… As I recall, it was fairly bitty at first, but the one song he did have completely finished was Waiting For A Girl Like You. The first time they played it to me, I said, ‘Well if that isn’t a hit, I don’t know what is!’”

Jones’ voice bears a tremor of emotion as he recalls the genesis of that song: “Waiting For A Girl Like You almost wrote itself. That was the first time I had a really serious emotional experience. It was overwhelming. From the moment we put down the basic track and Lou added a scratch vocal, I found it hard to be in the room without breaking down during the playbacks. It was such a strange sensation. I really got the feeling that something was coming down through me, that I was just the conduit. It was the first time I’d got in touch with what I’d heard other writers or artists talk about.”

That song would, of course, change everything – but so would the band’s choice of producer. Jones had taken both co-production and ‘musical direction’ credits on the first three albums – never less than fully involved – but was also keen to gain a respected second opinion on a song (or third, if it was one co-written with Lou Gramm). The man chosen was Robert John Lange (rhymes with “hanger”), a man known as ‘Mutt’ who was the big dog in rock production at the time, having steered AC/DC to consecutive multi-platinum successes with Highway To Hell and Back In Black.

Jones, though, had been a fan of his for some time: “‘Mutt’ first caught my attention when he produced a band called City Boy, way back [‘Mutt’ produced City Boy’s first five albums, starting with 1976’s self-titled debut]. I’d been impressed by the work he’d done on that band. And he had applied to do the Head Games album, actually. He came over to New York to see me, but it was just a question of bad timing for him, so we chose Roy Thomas Baker. But ‘Mutt’ was always in the back of my mind, so when he reapplied for the fourth album, that was it.”

Lange later became legendary for his painstaking, particular note-by–note work with Def Leppard, but was still a relatively unknown quantity to Jones, who insists he was unaware such methods might be used upon Foreigner. “I knew that he was really into sound, that he was dedicated and he was very serious,” says Jones. “He really showed incredible enthusiasm.”

The first evidence of that enthusiasm came during the pre-production stage when, having heard the songs that the band felt were ready to be recorded, he asked to hear the ideas that Mick considered unfinished. It was not something the guitarist felt comfortable doing, inviting this stranger into his hitherto-private world of taped bits and pieces.

Mick says Lange “forced his way into” this private world. “It was the first time I’d ever let anybody in there,” he adds. “In some cases, he was hearing stuff I thought was embarrassing. But he wanted to hear every single thing I had, even if it was only a 10-second snippet.

“Out of that process, we put Urgent together. It began as just an instrumental passage I had, the thing that became the intro. But I didn’t know what I was going to do with that. I thought it might become some sort of weird instrumental.

“‘Mutt’ also helped put Juke Box Hero together. It was originally two separate songs. Lou had one idea called Take One Guitar, and I had the Juke Box Hero thing. ‘Mutt’ helped us to gel the two…”

‘Mutt’’s contributions are openly acknowledged, but not recognised with the co-writing credits he later received with Leppard. It seems safe to presume he was handsomely rewarded, although ‘Mutt’ is never available for comment. The man who Jones, with a grin and no small degree of understatement, describes as “a bit of a recluse”, has made only one significant public statement in the last couple of decades: “I’ve always been a private person. I don’t value being in the media spotlight. I’m fortunate to be able to avoid it.”

English engineer Tony Platt, a man who worked with ‘Mutt’ on a number of albums before Foreigner 4, offers a first-hand view of his methods, and insists the producer is always artist-led. “One of ‘Mutt’’s absolute talents – and it is an exceptional talent – is insisting upon getting the songs right,” Platt says. “And he wants to get the songs right before you go into the studio, so you’re starting from a very strong perspective. In fact, the Foreigner 4 album got put back a couple of times, because ‘Mutt’ didn’t feel the songs were in quite the right shape. Even when I went out to theoretically begin recording, and they were still in pre-production, I ended up hanging around in New York while they were sorting out a couple of songs.

- Foreigner: Your Guide To The First Seven Albums

- Def Leppard: "Pyromania was selling 100,000 copies a day in the USA"

- The 11 best Foreigner songs, by Mick Jones

- Muse own up to Mutt Lange fears

“Then we took them into the studio and started getting sounds. That would undoubtedly suggest other changes that they might want to make in the arrangement of the song, strengthening the sound. The sound can then move further forward – and at a certain moment, we take a snapshot of it and then they could say, ‘That is how it should be. That is the moment in time that this song should inhabit.’ ‘Mutt’ was always very good at picking that moment, perfectly.”

History has proven ‘Mutt’’s infallible sense for what makes a hit record. But what was it like on the other side of the control room window?

Jones shrugs. “‘Mutt’ was intense. He was intensely dedicated to it, as well. We had our differences, you know. We were like two goats – stubborn – and we locked horns a few times…”

At a point that even the meticulous Platt can only recall as “late summer/early fall 1980”, recording finally began in the same studio where Head Games had been recorded: Atlantic Studios, on New York’s Upper West Side. However, it would prove to be a false dawn.

Platt: “It was a studio in which a lot of very good things had been done, but it had seen better days at that point in time. Atlantic had air-conditioning units that buzzed, and there were desks that were a little bit weird, so after about a week in there we just decided we had to go somewhere else.”

They would end up at Electric Lady, the legendary recording studio in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village that Jimi Hendrix had built in a basement he’d originally bought to turn into a nightclub. His earlier plan to make it a ‘curvaceous’ space with no right angles faltered, but as a studio it has endured. Jones had worked there in Spooky Tooth. Lange had used it for Back In Black.

Platt: “Both ‘Mutt’ and I had been very happy at Electric Lady, so we decamped and went there. Studio A is a big room. It still has the murals on the wall that were done when Jimi first bought it. It’s an astonishing space. It has a lot of vibe to it.

“So we set up… We created a large area for the drums, with a big screen set up for the bass. We built a room within the room for the guitar amps. I had to get as much separation as I could, but within a rock context – because I knew a lot of stuff might be replaced. And Lou sang all his vocals in the vocal booth that was already there. It was quite a large booth – and that became his home for all the time we were there! He kept bringing things in and making himself more comfortable.”

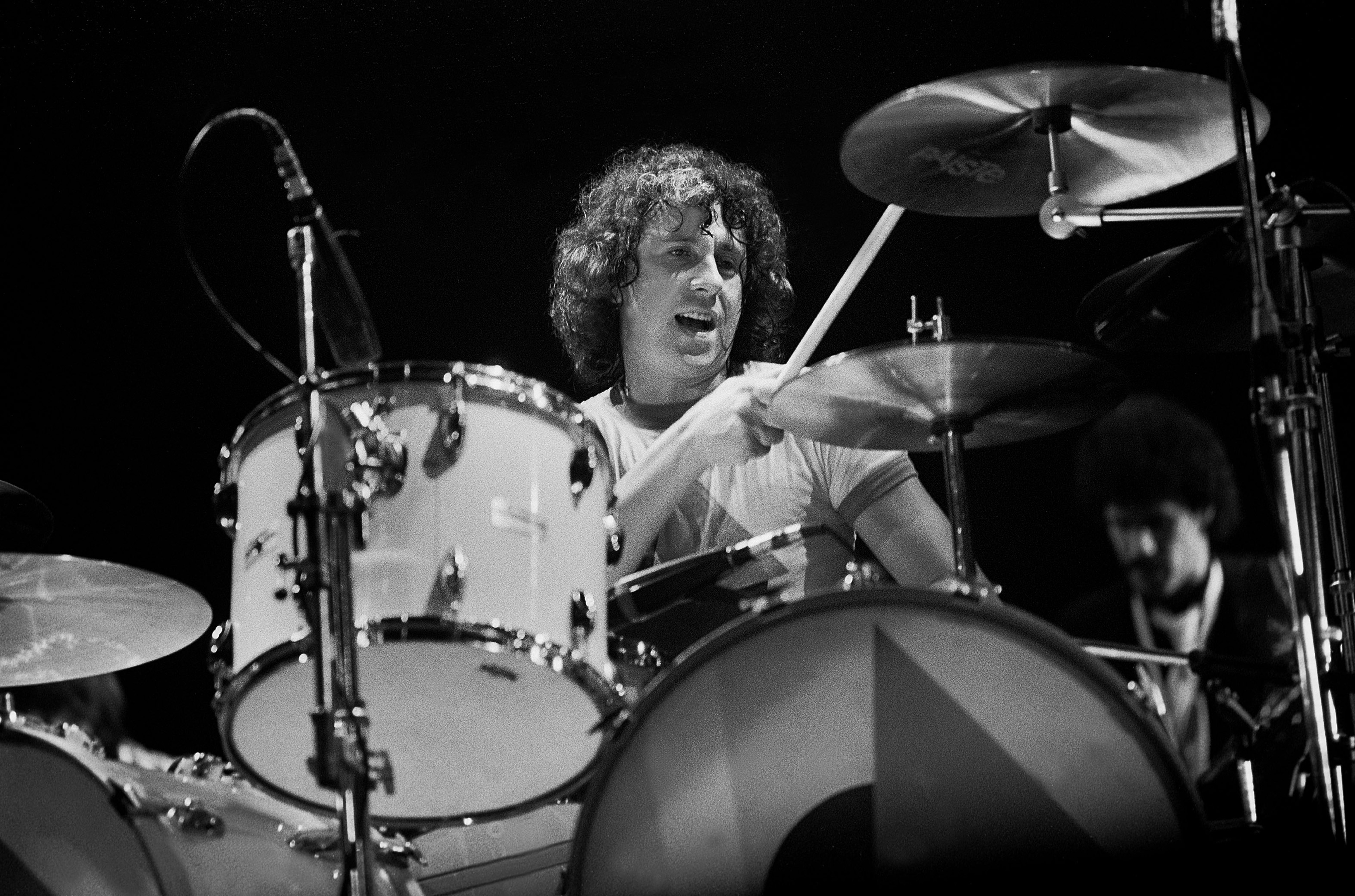

But first things first, and that meant recording Dennis Elliott’s drums.

“‘Mutt’ had wanted to go the electronic route with the drums,” remembers Jones. “That didn’t sit well with me or with Dennis. That was a bit of a bone of contention!”

Wills: “I remember for three days Dennis was just hitting snare drums. He finally got up and said, ‘Listen man, I can fucking play drums. You can’t even get a sound!’ He was really angry [laughs].”

Jones: “‘Mutt’ also wanted to use a click track for timing, and Dennis took offence to that, as well. When he and I were working on the song Break It Up, we got so fed up that, at one point, we just said, ‘Fuck this!’ and went into the studio together. I sat at the piano, Dennis sat at the drums, and we laid down the basic track, just him and me. Then we turned round to ‘Mutt’ and said, ‘Okay? Happy now?!’ We wanted to prove the point that this band could play and keep time, too.

“I guess I wanted to stay more old-school than ‘Mutt’,” Jones muses. “He was all for going ahead and using the technology that was coming up at that time – as you can hear on his Def Leppard albums, the drums there are electronic, they’re synthesised… But I didn’t want to go that route. It wouldn’t have worked for us.”

Today, Dennis Elliott – now retired from the music business and answering a new calling as a wood sculptor – seems reluctant to re-live all this, but recalls that his working life was simpler on the group’s earlier albums. “I was usually done with the drum tracks within the first two weeks, and the songs were then built upon those tracks.”

Elliott is a keen sailor, and during the sessions for Foreigner 4 he would moor his boat at a basin on the Upper West Side, where he lived with his wife Iona. The basin being a relatively short drive from Electric Lady, members of the band and ‘Mutt’ would often step aboard after a day in the studio, to unwind and enjoy the views.

Elliott, who might ordinarily have expected to be hitting the ocean by this point in the sessions, recalls: “I couldn’t really go too far, and it did seem to take an eternity. Sometimes a song would go through so many changes during that time, it was necessary for me to come back in and start all over… I would stop by the studio every week or two to see what progress was being made – but on the Foreigner 4 album, they always seemed to be playing foosball!”

Sometimes known as table football on this side of the Atlantic, Platt recalls that he and Lange installed the foosball table at Electric Lady. “We bought a table and put it at the back of the studio so, at the end of the night, we’d all unwind around it. We’d get the beers or the wine out, and have a tournament.”

Wills: “Every time there was any downtime, we’d go out there and play at the foosball table. We all got good – and got ferociously competitive about it. Especially ‘Mutt’…”

Platt insists he was the foosball champion – “Somewhere I’ve got the trophy, a miniature Converse sneaker” – which Jones confirms. But, as Wills observes, “at $2,000 a day, it was quite an expensive hobby!”

According to the bassist, very little work seemed to be getting done. “It was hard to get the gist of where we were going to go with this album, because after just about every session, there would be this long conversation, between Mick and ‘Mutt’, about where we were going with the album and what was needed. If ‘Mutt’’s anything, he’s a perfectionist. He doesn’t let anything slide, won’t let anything past him unless he thinks it’s good enough. And Mick Jones is pretty similar – so boy the two of them did lock horns a few times. It was tough!”

Everyone agreed, though, on Waiting For A Girl Like You.

Wills: “That was one of the first songs we recorded – kept and done as a second take! It sounded fabulous. Everybody’s performance on it sounded great and we knew we had that in the can.”

“Waiting For A Girl Like You was Lou’s original live vocal,” says Platt. “That was one of those tracks where I remember the recording session very, very clearly. We put down a basic washy keyboard in the background, with the main track. There was some editing in between takes… And once we’d chosen the master and done all the edits, I remember sitting there till about three o’clock in the morning, and everyone was still saying, ‘Oh, play it back again, play it again!’ There was a general feeling that this was going to be the big hit…”

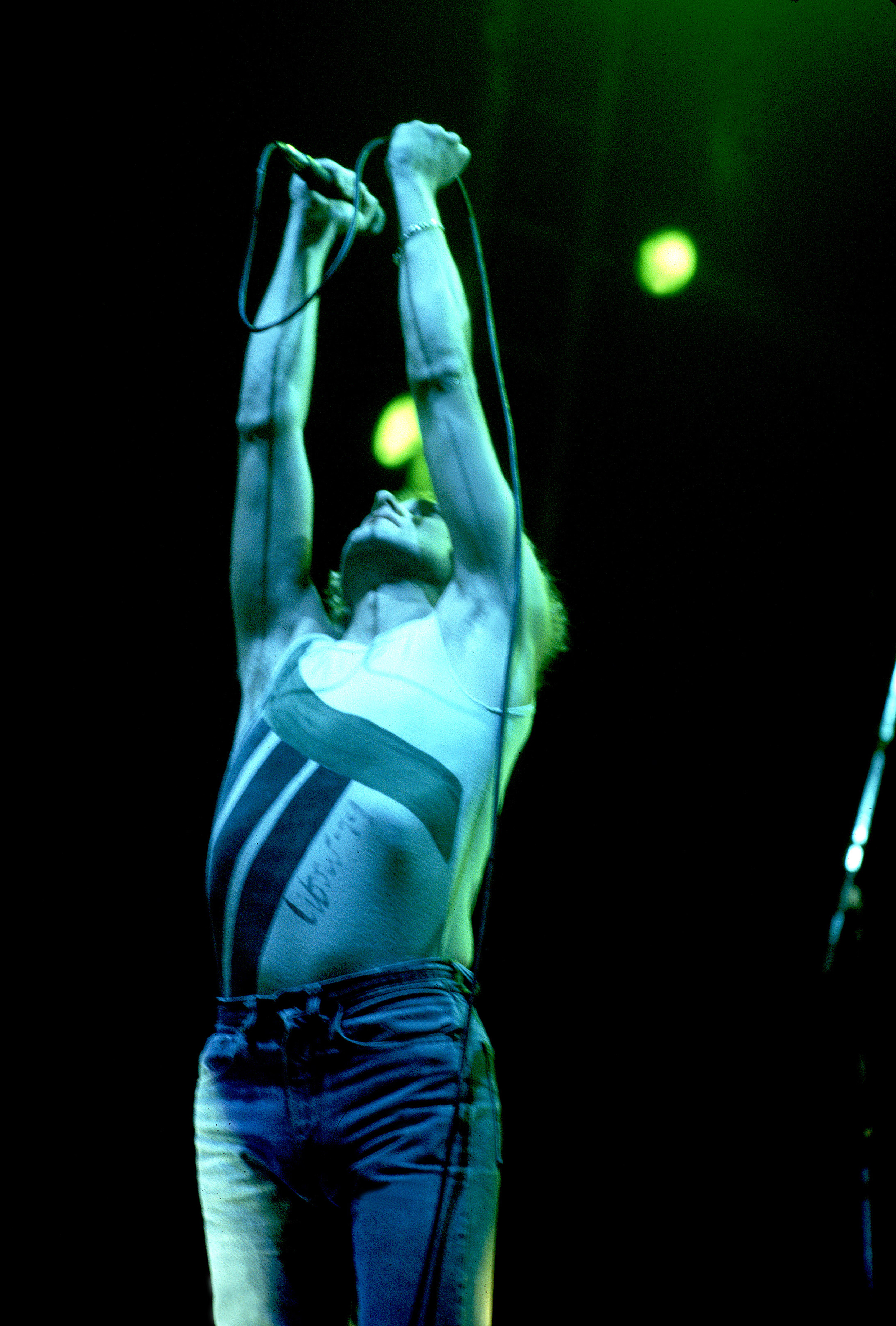

What no one appreciated while listening to Waiting For A Girl Like You, however, was that Gramm was not going to be able to replicate its incredible chorus live.

Jones: “In hindsight, I’d say ‘Mutt’ really pushed Lou, probably past his range. I was there as well, so I have to take a bit of… I don’t know about blame, because it all worked out as we all wanted it to work out. But in hindsight, Lou did have a lot of difficulty with the pitch and the range of a couple of those songs. Juke Box Hero was another song that strained his voice to the limit.”

Wills: “Lou could sing it in the studio, but he couldn’t reproduce it live every night. We actually used to do it a semitone down from the record. We used to detune – we had separate guitars for that song. Same with Juke Box Hero. It was just too much for Lou to do. It led to some sort of mind games going on between him and Mick about performances and stuff. That’s how the whole thing started to disintegrate later on in our careers, really, with Lou not being able to really cope with the demands.”

At the time, though, Wills reckons the singer was unfazed by most of what was going on: “He just dealt with it in Lou’s way – very quietly and subdued. Although he was very much involved in the writing side with Mick, when it came to the recording he would make suggestions, but pretty much let Mick and ‘Mutt’ run the show…”

That show was gradually running around the clock. They might take the occasional day off, but recording was becoming a way of life.

Wills: “Electric Lady became our second home. We initially began sessions at midday, but three months later they’d gone on so long that we were starting at midnight.”

Like Dennis, Mick and ‘Mutt’ were holed up in the city. Lou Gramm and Rick Wills were commuting from their homes in Westchester County – about 45 miles, or a 45-minute drive, from Manhattan. This was “no big deal” according to Wills, who preferred to “go back to his home and his family every night. Or whatever hour it was. Sometimes I’d get back at 6am, just as they were getting up to go to school… It was pretty bizarre!”

Their shifting schedule ultimately led to the lyrics for one of Foreigner 4’s songs. Nearby the studio, on the corner of Sixth Avenue, there was a Nathan’s Famous hot dog eaterie, as Jones recalls: “The later it got at night, the bigger the buzz got, and a lot of weird characters, some of them hookers, would appear. It was a big mixture of a lot of different characters – so that was the inspiration for opening song, Night Life.”

However, the extended studio hours were taking their toll financially.

“At the time it was considered unrealistic,” says Wills. “We’d spent over a million dollars in recording costs. There was a lot of pressure – from the record company, from the management and from ourselves. It was pretty tough. Our manager, Bud Prager, was going crazy, having to keep going to Atlantic for more and more advances, just to pay for the studio time. Because once you’ve got that far into it, you can’t turn back, and you begin to realise that you’re going to have to sell a hell of a lot of records to pay that advance back…”

Steadily, though, great tracks started to emerge, including songs like Urgent, which had barely existed when sessions first began, and was, at one point, stripped right back to Elliott’s drum track and that quirky guitar intro.

The song, however, is made by the sax solo played by the late, great Junior Walker. Jones saw Walker and his All-Stars were playing in a club nearby, so he and Wills skipped out of Electric Lady, watched three or four sets, and then invited a bemused Walker down to the studio.

Elliott and his wife made sure they were there to see the soul legend in action. “It was very amusing,” remembers Iona, “because after he played his solo once, he was very happy with it, but Mick made him play it several more times, and was trying to get him to stretch out more and more, until it became that wonderful solo.”

“It turned out that in all his career he had never done an overdub,” adds Jones. “Everything he’d ever done was live. So the first five or six takes, he was really uncomfortable. He had the headphones on, but couldn’t get used to that fact that he was overdubbing. But he did, after a while, and started playing some stuff. He explained, ‘I’ve kind of changed my style up a bit…’ and started playing this jazzy, softer type of stuff. ‘Mutt’ and I were sitting there thinking, ‘Oh, no, we need the Junior Walker we know and love.’

“‘Mutt’, bless him, went and straight-talked it to Junior: ‘This is great but we really need some of that Shotgun/Road Runner stuff.’ ‘Oh, you want the old shit? Okay!’ So he gets up, does it again and in two or three takes we’ve got it. However, it did take a tremendous amount of editing. ‘Mutt’ and I spent two days chopping up little slivers of quarter-inch tape from the different takes, and then splicing it all together. We wanted it to be a classic solo, and I think that’s how it ended up…”

It’s tempting to paint Lange as the villain of the piece, but, as the Junior Walker story shows, Jones was just as much a perfectionist. Today, he concedes: “We had these moments with ‘Mutt’, but we kind of overcame it. Nothing lasted longer than the time it took to achieve what we’d set out to achieve. Gradually, things eased up with ‘Mutt’, and we really started to appreciate what we were all bringing to the party. He loosened up from his more ‘stiff’ approach.”

After three months, however, Platt had to leave. He’d stalled a prior engagement to re-mix Samson’s Shock Tactics LP, but could delay the project no longer.

- Marriage: Mick Jones

- Foreigner: First Time Around

- The Top 10 Most Underrated Foreigner Songs

- Foreigner in talks over Lou Gramm return

Platt: “I would speak to ‘Mutt’ now and then, of course. If he ever had any questions on anything I’d done, he’d just call me up. It was all recorded in 24-track analogue. Those tapes already had a lot of edits in them, so you wouldn’t want to keep playing them. The normal practice in those days was to make up a slave reel from the master reel so you could do all your overdubbing on the slave reel – then you would lock the two together when you did the mix, so you wouldn’t be degrading the sound on the master reel, by playing it over and over again. So before I left I made up all the slave reels and checked everything was right before I left.”

The other thing Platt did before leaving was recommend his replacement, Dave Wittman, the man who would carry the torch as Lange’s right-hand man to the very end of the project.

Initial sessions had seen Platt record keyboards by Peter Frampton’s Bob Mayo, sometime Lou Reed man Michael Fonfara, and Larry Fast from Peter Gabriel’s band. But ‘Mutt’ and Mick wanted something more. They went after a then-unknown Englishman by the name of Thomas Dolby, who could be found busking in Paris, avoiding a UK music lawyer’s bill he couldn’t afford…

Dolby: “I got a call from a friend in England who said, ‘Somebody called Mick Jones phoned for you and said he wanted you to do a session…’. I thought this was Mick Jones of The Clash, who were one of my favourite bands at the time. I’d actually never heard of Foreigner. But when I looked into it, it turned out that they were actually very big in America!”

Lange, a partner in Zomba Publishing, had heard one of the 22 year old’s demo cassettes and liked his keyboard playing, so, in mid-January 1981, he suggested to Mick that they should check Dolby out.

“I spoke to them from Paris and they suggested I should try out for a day or two and asked, ‘When could you come over?’,” remembers Dolby, of the initial contact. “I thought very hard and said, ‘Well, tomorrow morning!’

“‘Mutt’ was really sticking his neck out in insisting that they hired me and fly me over. I was a kid who had previously thought himself lucky to have spent four hours in a recording studio. I was like a bull in a china shop – ordering up all sorts of keyboards and effects, from a list like a takeaway menu.

“They’d already put keyboards on most of the album, but they weren’t very happy with them, so they gave me a trial to see what I could do. The first track they gave me was Urgent, and they were very pleased with that so they asked if I could stick around and do the whole album.”

Mostly, Dolby’s contributions consisted of very subtle keyboard arpeggios, doubling every note Mick Jones and Rick Wills had played.

‘Mutt’ could then add yet another layer to the mix but, as Dolby explains, “he’d make it very, very quiet, so you could hardly hear it. That would just make the guitar playing sound better… I think I was on pretty much the whole album.

“Waiting For A Girl Like You was clearly the centrepiece of the album, but they were nervous about it, because they weren’t really known as a ‘ballad band’. But they were also very confident about it, and ‘Mutt’ Lange, in particular, was absolutely convinced it would be the biggest hit they’d ever had. He said, ‘I really want to make this remarkable. Every time this comes on the radio, I want people to prick up their ears and know exactly what they’re listening to.’

“I was very heavily influenced by Brian Eno and his ambient stuff, and I had a style like that. This was in the days before polyphonic synths that allowed you to play chords. Back then you could only play one note at a time, but you could build up chords on a multi-track by playing long single notes and layering other notes above and below them. It would vary the sound a bit, and you’d end up with a nice mesh. So I recorded a few minutes of that, and ‘Mutt’ came in and took a slice of it – maybe 25 seconds or so – and spliced it into the front of the song. And it worked rather well!

“I remember, a couple of years later, I’d be driving in middle America somewhere, listening to some AOR rock station, and this sound would come on. It was absolutely unmistakable. I felt it was quite subversive, really, to get some ambient Eno music on to American AOR radio!”

For Dolby, who to that point had “barely made a penny” as a session musician, one month’s work changed his life. “I came back from the States with an envelope full of cash, which I used to make my first album, so the proceeds from Foreigner 4 set me up. By the time Waiting For A Girl Like You came out, then suddenly I had all sorts of option for other work…”

Despite that cash – which led directly to his 1982 debut album The Golden Age Of Wireless, and early hits Windpower and She Blinded Me With Science – Dolby recalls that “they were trying not to break the bank, so I actually stayed in ‘Mutt’’s hotel suite on Central Park South. It had a pull-out settee in a second room, and I slept on that for the first week or so. I remember that ‘Mutt’ would leave for the studio in the morning, before I woke up, and often wouldn’t get back until after I was asleep. The man slept, like, four hours a night! And yet he still found time to sit cross-legged on his bed, playing guitar and singing like Van Morrison. Really extraordinary. He was a very interesting man…”

By the time Dolby arrived, Foreigner had been in Electric Lady about six months but were, it would transpire, only two-thirds of the way through the process. “They would work during the day on vocals and mixing, and at night I was set free in the studio until they came back in at nine o’clock in the morning.”

Jones: “We would give him a load to do, then go out to dinner and just leave him there. Then we’d come back to hear what he’d put on…”

The painstaking work continued with some unusual distractions. Next door to Electric Lady is an art-house cinema called the 8th Street Playhouse. After a late-night showing of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, one of the punters had inadvertently left his seat gently smouldering. Some hours later, smoke was seen pouring out of the cinema; next door, in Electric Lady’s control room, Mick Jones could smell something burning.

“We thought at first the fire was on our side,” he remembers. However, thoughts of countless hours of work being lost were suddenly interrupted by a loud banging on the wall.

Dolby: “Suddenly members of the New York Fire Department came through the wall of the studio with axes. They were very big, beefy guys, and all I could think was that they looked like the Village People…”

Electric Lady survived the intrusion and work resumed. Soon, Dolby’s work was done and he flew home. But for Jones and Lange, pressure was building. Their time at Electric Lady was about to hit a brick wall as the next client, Hall & Oates, refused to budge again. Worse, ‘Mutt’'s booking to produce Def Leppard’s Pyromania had also been put back for the last time. Eventually, he simply had to let go of Foreigner…

Jones: “‘Mutt’ stayed absolutely as long as he could. It was gut-wrenching for him when he had to leave, but he had to… Def Leppard was already three or four months over schedule. We’d been through this intense time together, the best part of nine months, so it really was gut-wrenching.”

With ‘Mutt’ out of the studio – though still in touch on the phone, and listening to mixes couriered across the Atlantic – Jones ended up adding the final touches, mixing and sequencing with engineer Dave Wittman. This lasted around four weeks, from March through to April. With just 10 days of studio time remaining, Jones took the drastic step of taking a bed into the studio and sleeping there rather than lose focus.

Jones: “We’d got into this thing where the studio was like my den. I didn’t even go outside.”

Wills: “He was almost going mad, truly!”

Come the final seven days, Jones and Wittman reckoned they still had 10 days of work to do. With “Hall & Oates’ roadies in the corridor delivering their gear”, they were completing the final song. Meanwhile, Lange and Prager opened what was supposed to be the final mix of Foreigner 4.

Jones: “I get this call from ‘Mutt’, and he says: ‘Where are the fucking background vocals on Juke Box Hero?!’ Then my manager called up, asking the same thing: ‘Where are the background vocals?!’”

Jones admits he had removed them on purpose: “It was some ridiculous idea I’d had… I tried to explain this as a creative decision, but they both said I was crazy and insisted I put them back – at which point I realised I’d made the wrong decision, somewhere in those last 10 days of madness.

“So I go see Dave and say, ‘I think we may have fucked up, here! How can we fix it?’ He just said, ‘Don’t worry!’ and rushed back in. Juke Box Hero was so intricate that we’d used every single cable and every single piece of equipment in the studio. Dave and I had all four hands on the desk. Within two hours, he had re-established the set-up – all the equipment, the cabling, the faders, everything and remixed the whole chorus section of the song again. It was just his recall from a completely different mix. And by some miracle it fitted back in – with just a little bit of level adjustment – the choruses and the rest of the song are from two different mixing sessions. It was miraculous. And that was the very last thing we did!”

A fittingly fraught ending to the marathon process, a stroke of luck that was well deserved after all the hard work before. The band took the songs out on the road… and the rest is rock’n’roll history. Asked to reflect on Foreigner 4 today, Jones pauses thoughtfully before answering. “It was definitely the sum of what I thought we’d been building towards. When I look back on it I know it’s my favourite album. I know the process was long, gruelling and costly – costly not just financially, either. Relationships got strained during that album. Domestic situations got out of control. There was a lot of intensity involved in that. But looking back it’s the one I always say I’m probably the most proud of.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock Presents AOR 3 - Foreigner 4.