Has anyone outside the band’s fan following – more a communion than anything – ever made sense of the Grateful Dead? To some they remain the ultimate arcane cult band, too hands-off for general consumption; the lost symbol of what rock music was like before the man, in the guise of corporate marketing, worked out how to fleece us all.

Perhaps they were too parochial. Even their latter-day publicist, Dennis McNally, admitted it was a struggle to explain the band to the uninitiated. “It was always a challenge because there’s so much distraction about them,” he said. “But if you ignore the rabid fans and the expected facts of American entertainment, there’s a richness that fills your soul. They explored freedom and gave us a phenomenal revaluation of American values.”

In Don Henley’s song The Boys Of Summer, Henley pictured their myth as a disappearing dot on the horizon. “I was driving down the San Diego Freeway,” he said, “and got passed by a $21,000 Cadillac Seville, the status symbol of the right-wing, upper-middle-class American bourgeoisie – all the guys with the blue blazers with the crests and the grey pants – and there was this Grateful Dead ‘Dead Head’ bumper sticker on it!”

Keith Richards didn’t get them. “The Grateful Dead is where everybody got it wrong. Just poodling about for hours. Jerry Garcia: boring shit man. Sorry, Jerry.”

Richards gave his opinion in the wake of the Dead’s Fare Thee Well shows at Chicago’s Soldier Field on the July 4 weekend of 2015, where they bid adieu and walked off with a cool $55 million gate, gross. Perhaps Keith, a pensioner with benefits if ever there was one, was merely miffed about that bottom line.

Of course, the Grateful Dead sold out like everyone else, but a fascinating new Amazon documentary called Long Strange Trip puts them back into focus. Neither damage limitation nor a rescue mission, Long Strange Trip provides a suitably fuzzy cultural framework and enough transcendentally euphoric music to delight the devotee and maybe sway the ‘don’t give a fuck’ anti-Dead brigade.

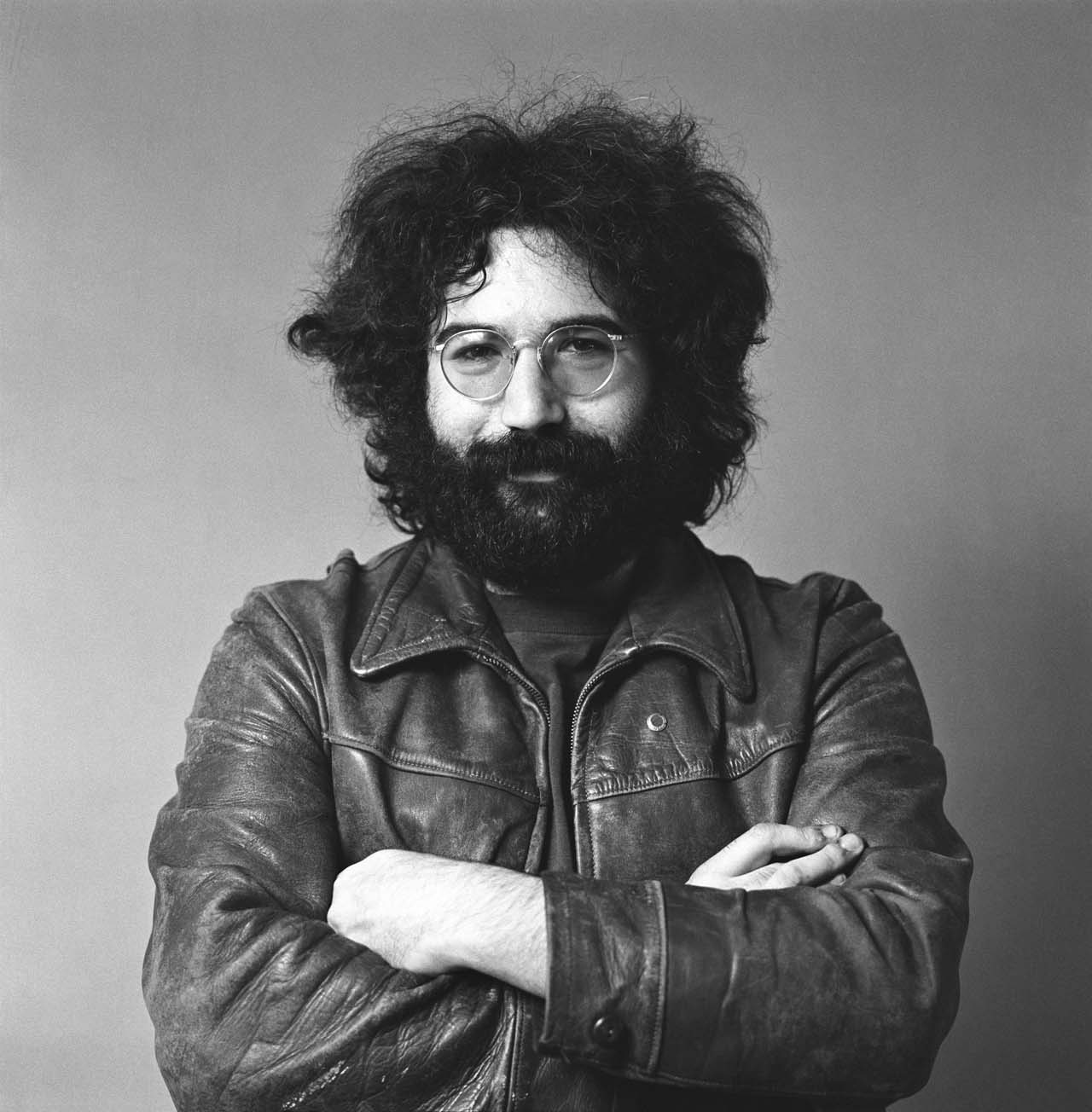

Directed by Amir Bar-Lev and executive produced by Martin Scorsese, Long Strange Trip spins the clock back to the beginning, when Jerry Garcia was a five-year-old kid watching Abbott And Costello Meet Frankenstein in 1948, a year after his father had drowned in a fly-fishing incident in northern California.

Garcia said: “It might have been the dead thing brought to life. Frankenstein’s monster is, after all, a drive to reanimate, or to produce life, and it hit me in that archetypal centre.” At that point, he decided, “I want to be concerned with weird.”

Garcia created his own monster when he gave up wanting to be a bluegrass star like his hero Earl Scruggs, or a beatnik jug-band novelty act with his oldest friend Robert Hunter, instead hitting the electric switch. Fuelled by the left-wing politics and Cold War paranoia of the early 1960s, Garcia hung out in bookstores like Kepler’s in Menlo Park, discovered cannabis and lost faith with reality.

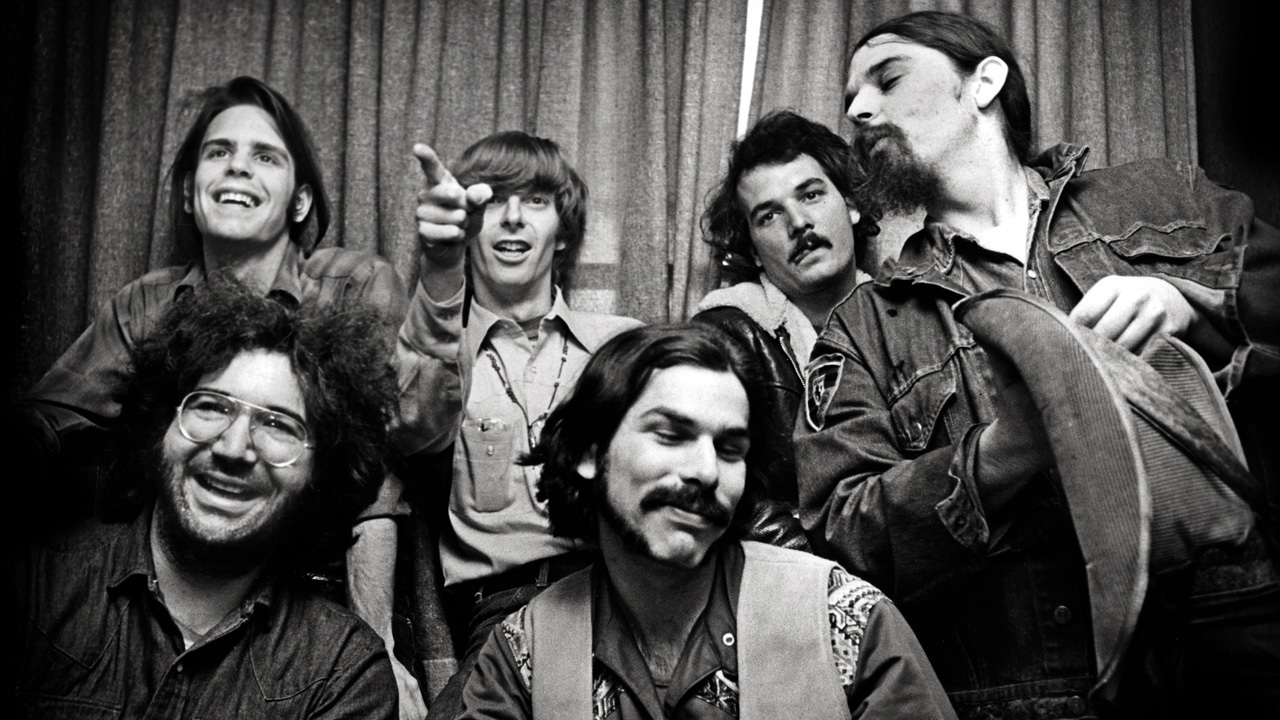

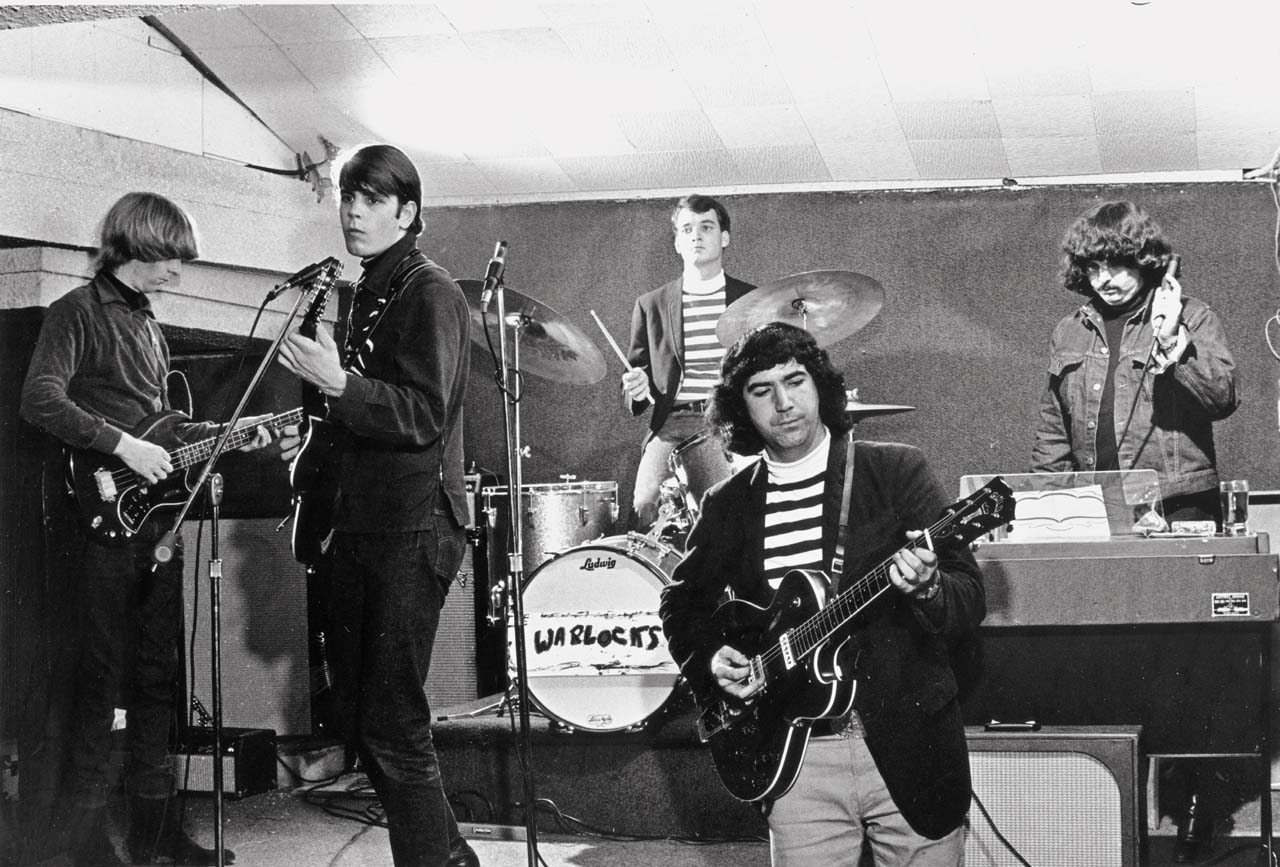

He met Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKernan, whose father sold Garcia a banjo. Since Ron was an R&B fanatic he became the frontman. A long-haired teenager called Bob Weir had gravitated west from Colorado and, hooking up with Hunter, McKernan and Garcia, they became The Warlocks. Avant-garde composer Phil Lesh was brought in and told he was the bass player, although he’d never touched the instrument. The drummer was a natty-looking mod called Bill Kreutzmann who, like Weir, was underage and couldn’t legally play in bars.

The Warlocks were okay, though very rough round the edges, and when they discovered that the prototype Velvet Underground on the East Coast also had that name, they might have called it a day. However, Garcia held one last band meeting in Palo Alto where they thumbed through a dictionary until the guitarist saw ‘The Grateful Dead’, a folklore reference to a dude who pays for the burial of an unknown corpse. “It was creepy, and only me and Phil liked it, but it was a striking combination of words,” Garcia said.

The new band house in Haight-Ashbury became the crucible. “We learnt precision and technique,” according to Weir. “It was fairly rigid, with lots of practice.”

They still didn’t have much style, since Garcia was holding on to his folk roots. “But that was too much frozen technique,” he said. “It got sterile and inhuman, so I murdered it and went electric and we got a reaction.”

One of guitarist Bob Weir’s slogans for the band was ‘Misfit Power’. Plenty of misfits enrolled.

As their idiomatic purity dripped away, they began a residency at Magoo’s Pizza, mutating The Warlocks into the original Dead, playing five sets a night, six nights a week. “That made us good,” recalled Garcia. “We were young enough to love the hard work.”

What happened next had fundamental significance. The band began to hook up with Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters, whose motto ‘Never trust a Prankster. He will lie to you’ appealed. So did the ready availability of the still-legal psychedelic drug LSD that the US government used on its own troops in experiments akin to chemical warfare. Kesey had a stash of the drug, and he started to hold Acid Tests, where Garcia and the boys became the live entertainment.

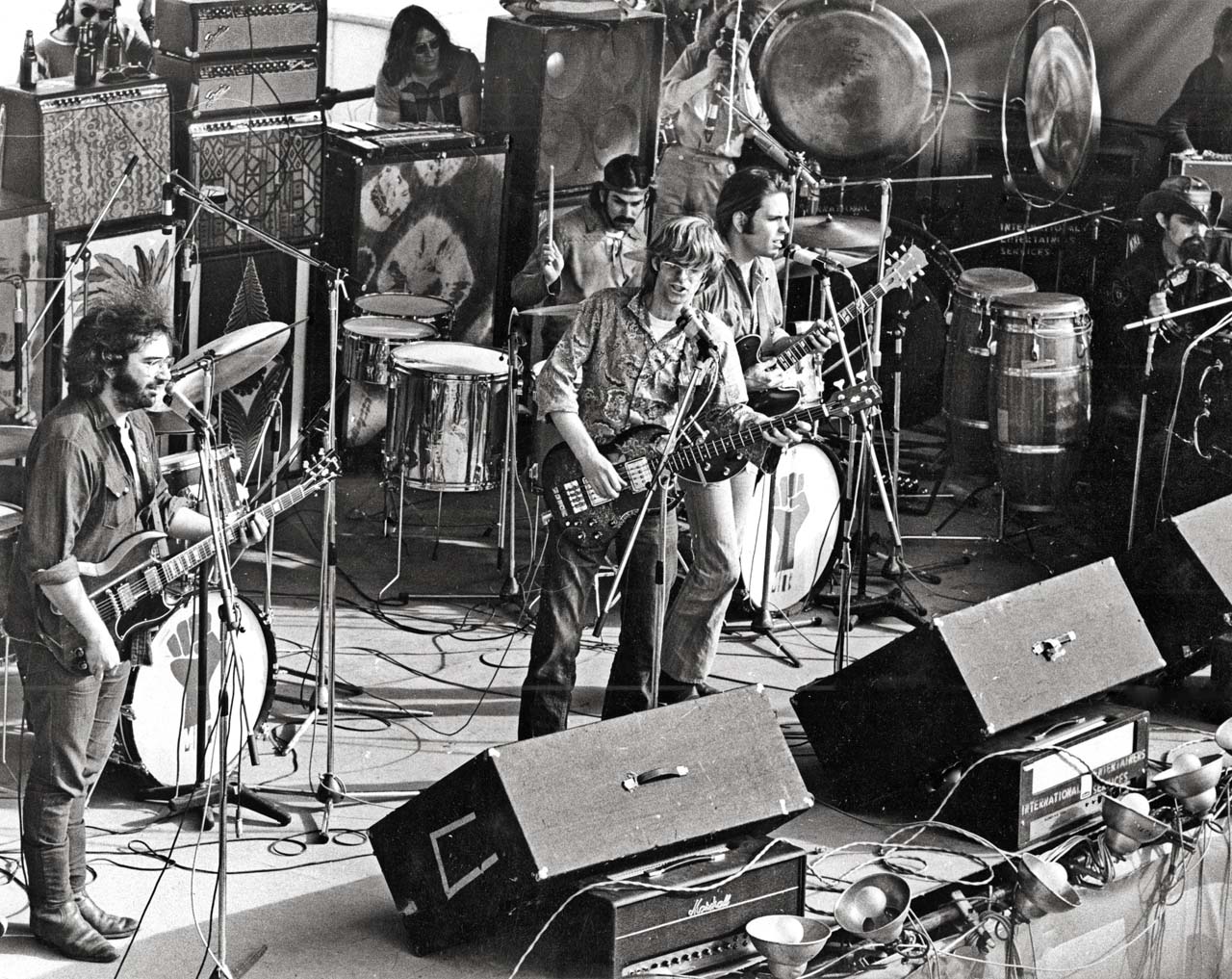

“It was a dollar to get in,” Lesh recalls. “We weren’t famous and we weren’t even required to play, but with Pigpen out front we played a few tunes and discovered freedom. There was communication from the audience, not in words but fragments of ideas. That’s how we evolved and learned to listen to each other as musicians.”

The 16-year-old Weir thought “a lot of that stuff was dangerous, not always in a bad sense”, but Kreutzmann ditched his preppy attitude. “The camaraderie was incredible,” he said. “We saw how we could escape to another place.” For Garcia, “discovering acid was the single most significant experience in my life.”

In February 1966, Garcia had an epiphany after performing at one of Ken Kesey’s famous Acid Test parties, where LSD was served like liquor. He realised he had no desire to build something permanent. Instead he wanted to create something “flowing and dynamic,” and “not so solid you can’t tear it down”.

There was a feeling of peaceful rebellion gathering force on the Haight, where rents were cheap, the Victorian houses lovely and a steady stream of artists and beatniks coalesced to form the nascent hippie movement. “It wasn’t really a revolution,” said Garcia. “I didn’t want to hurt anybody, just wanted an uncluttered life.”

The band’s home at 710 Haight-Ashbury became a commune, with what Weir calls “a lot of bitching about the milk, that kind of deal. It was a family. We played every day until we became like a bunch of fingers.”

In 1967 the Grateful Dead recorded their first album, fuelled by speed and acid. Warner Brothers Records signed them on a whim – their wildest acts were Trini Lopez, Peter, Paul And Mary and Petula Clark – but only because RCA had already beaten them to Jefferson Airplane.

Unable and unwilling to provide the label with anything remotely commercial, the Dead delivered the experimental Anthem Of The Sun and Aoxomoxoa, whose signature tune China Cat Sunflower might have done the trick, before finding their feet with Live/Dead, using 16-track recording and flaunting a newly professional stance.

New second drummer Mickey Hart, whom Kreutzmann met at a Count Basie concert, added Eastern polyrhythms and left Kreutzmann to swing. It was a beatific moment for Garcia, who thought the six-piece ensemble (pianist Tom Constanten was “never a card-carrying member of the Grateful Dead”, says Kreutzmann) so good “we can take this round the world. I wanted to get everyone up and dancing, but then that became a lie when I realised I couldn’t guarantee anything.”

The ill-fated concert at Altamont, which the Grateful Dead’s manager Rock Scully helped organise, was a watershed moment. Learning that a black kid called Meredith Hunter had been beaten and stabbed to death by Hells Angels, and their friend Marty Balin from the Airplane had been knocked unconscious, the Dead got the hell out and headed home long before their own set.

Immediately post-Altamont, the Rolling Stones’ stage manager, English-born Sam Cutler, handed in his notice to Mick Jagger and befriended Garcia, who asked him to oversee the Dead’s first UK visit to England in 1970, where they played at the Hollywood Festival in Newcastle-under-Lyme. After the Stones, the Dead seemed like rubes to Cutler.

“Me and Garcia smoked a joint, and after thirty minutes he said: ‘If the music business is a forest, then you come to a thicket, a break in the grass, and there’s a patch of light and the smell of flowers. Well, that’s the Grateful Dead.’ For fuck’s sake! But that’s how they are.

“When we came to England they hadn’t been abroad – they knew nothing about the money. They didn’t know the difference between a shilling and a pound, though the fact we called our money LSD in pre-decimal days was found hilarious.

“They hired me cos I’d toured the Stones, and Garcia was fascinated by how they rolled their trip. The Dead actually had no idea about being in a major band and what it involved. They were like naïve children in a man’s world. But what they did was to redefine what it was to be an American artist. It was like a constant struggle. And they had that American thing of, ‘Wow, let’s go and discover America,’ whereas the idea of going off to discover England would be ridiculous.”

To ensure he didn’t drop the ball, Cutler was the only person in the entourage who never travelled with drugs. “Didn’t need to. Whenever I needed them I could find them within thirty minutes.“

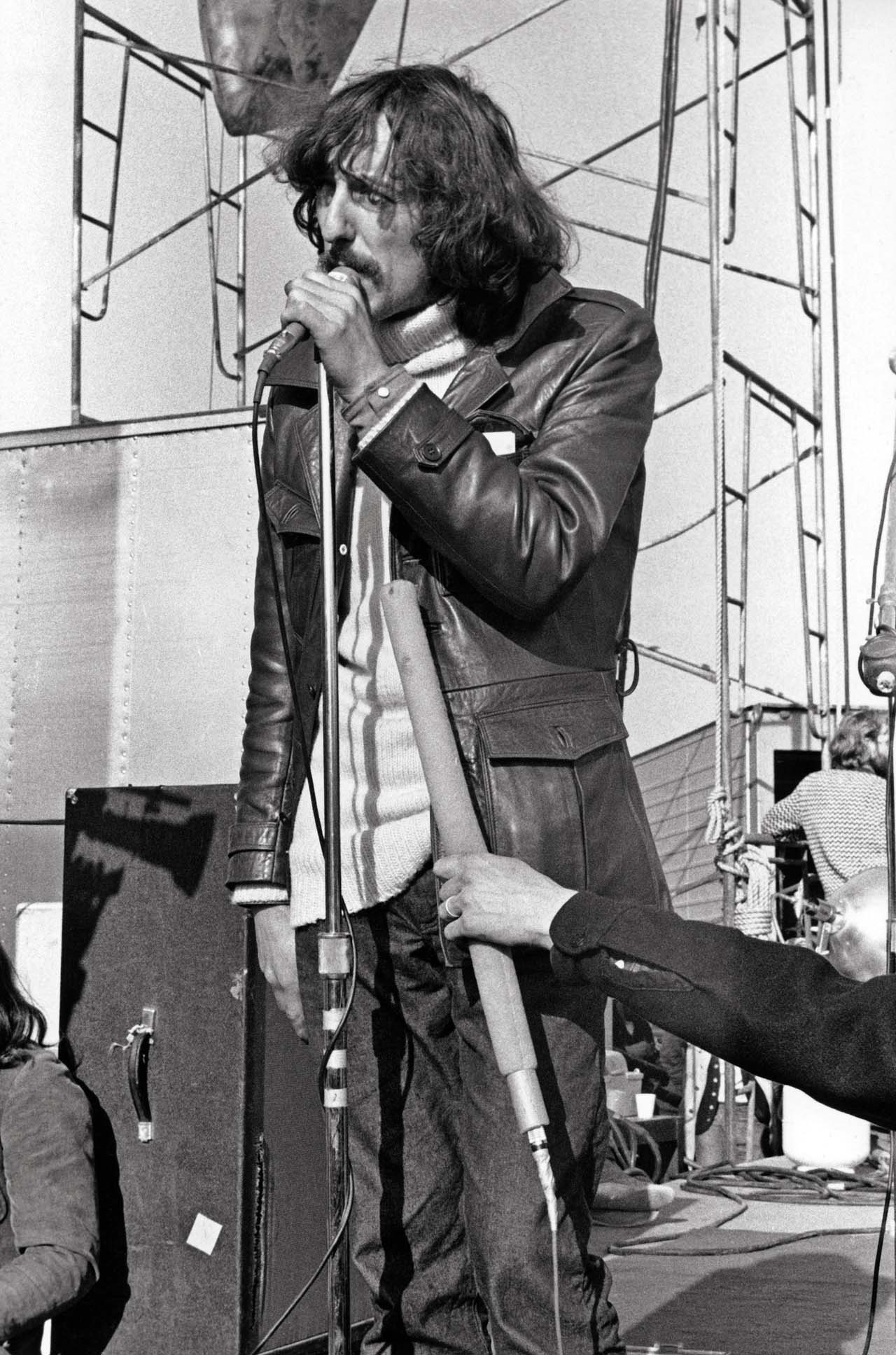

In London, the Dead took their Super-16mm cameras out sightseeing. They went to the same stretch of the River Thames where Ringo Starr walked along the Kew towpath in the Beatles film A Hard Day’s Night. They also filmed a Warners press conference where every time the lens was stuck in front of Pigpen he pulled his hat down – “I ain’t saying nuthin’.”

The era of classic Dead began in 1970. They released two brilliant albums – Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty – both influenced by the close harmony singing of Crosby, Stills & Nash and The Band. For the Workingman’s Dead sessions they hung a sign on the door at Pacific High Studio in San Francisco that said: ‘Trespassers will be eaten.’

Behind closed doors, Garcia taught himself pedal-steel guitar and put the others through a ferocious pre-song ritual. He’d sit on a stool with his acoustic guitar, and whip Lesh and Weir, perched in front of him, into shape until they could make the notes on what was virtually a solo Garcia-Hunter concept.

Joe Smith, who had signed the band, and Warners were delighted with the product. “The previous two albums were like drones – nobody played them on the radio,” recalls Smith.

Garcia explained their MO: “It’s trial and error. A lot of error! One full moon, Weir said: ‘Let’s go to the zoo and record the animals.’ We were so high. Or he’d say: ‘Let’s go hard out, hot and smoggy, and record clear air and do that as a real track.’”

They manhandled Smith, who was completely straight, into partaking in their helium-tank high jinks. “Aoxomoxoa was by far the most expensive project Warners ever had and they still wanted more money,” he said. “They insisted they could be commercial and they came in with that Aoxo… album? I still can’t pronounce it.”

To Lesh it was all about “the moment and collective improvisation. When we were really on it, we could open the valve. And if the company didn’t like it, we didn’t give a shit. Fire us. We don’t care.”

To Kreutzmann, “it was keeping the feeling. I never kept time, because we wanted it to go so far out that you don’t know what the song is. As long as it’s just fucking outrageous, just keep playing.”

Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty finally offered a way out of the fog. Warners backed their hunch and took out huge billboards saying: ‘Honor the Dead’. Their errant charges responded by shaping up. There were plans to perform in Hyde Park because their festival experiences, apart from Monterey, had been disastrous – their half-arsed Woodstock slot and the Altamont no-show hadn’t improved their wider profile.

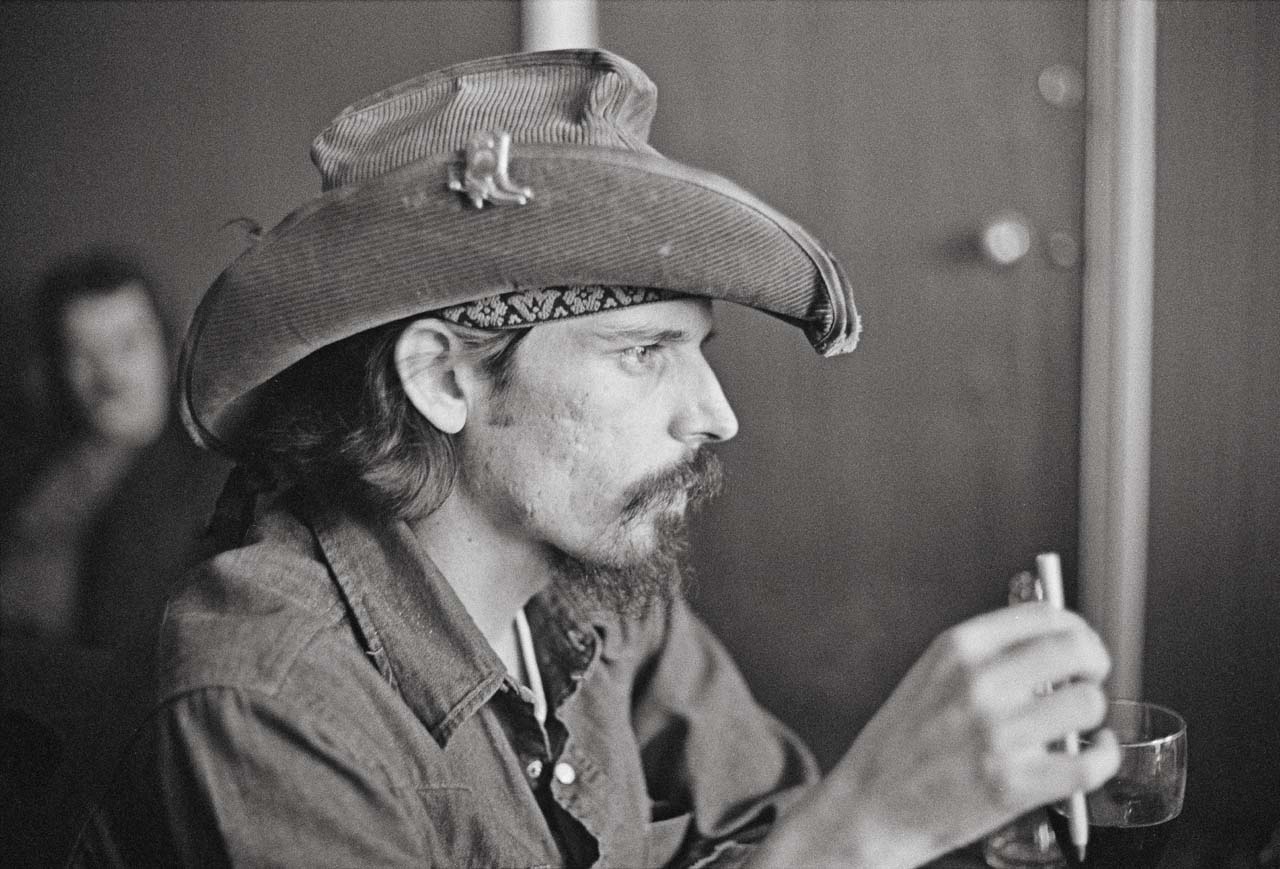

Now the audience was starting to grow, Garcia kept the Dead on the road constantly. Pigpen wasn’t always around – his health was poor, his liver lacerated by constant boozing: brandy, Jack, Southern Comfort. He made the Europe ’72 tour, where it was obvious his place in the group was at risk. He was a blues guy, and, with his cowboy hat, white vest and beard, the persona of the Dead to many. He looked like a biker and sang it rough, especially during his beloved Turn On Your Love Light that generally ran to thirty minutes in the early 70s. The trouble was, when the shuffle turned into a triplet, he couldn’t deal with the changes and just fell by the wayside, standing somewhat pitifully stage left.

As the LSD communion was going on around him, Pigpen warped out and deliberately drank himself to death. After he died on March 8, 1973 from internal haemorrhaging, aged just 27, the Dead’s acid scientist Augustus Owsley Stanley (aka Bear) commemorated him on the album History Of The Grateful Dead, Volume One (Bear’s Choice). Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKernan was buried in Alta Mesa Memorial Park, Palo Alto, with an inscription that reads: ‘Pigpen was and is now one of The Grateful Dead forever.’

After McKernan, the Dead got huge. Their new sound system, known as The Wall Of Sound, was an outrageous monolith designed by Owsley. Financed by the acid king’s illicit fortune, it was the biggest PA ever built. Lesh’s bass stack alone was 32 feet high. The entire rig contained 500 speakers. It drove the band’s crew mad, but for a while they persevered.

The Dead’s crew were legendary in their own right – punchers and cowboys who rode Harley-Davidsons and fired shotguns in battles with San Francisco band Quicksilver Messenger Service on their respective ranches. They shared the same women and got righteously messed up, but they worked like dogs. They were part of the invading swarm that came to England in 1970, ’72 and ’74, by which time they and the band were living in a cocaine-fuelled world, with plenty of heroin, nitrous oxide and booze to boot.

To tour organiser Sam Cutler it was “becoming a nightmare. They were dumb about business and every decision was the collective.”

Backstage they were always visited by the local Hells Angels MCs. Reality wasn’t on the agenda. The Angels made most people nervous, but Garcia insisted there was a seat at the table for evil as well as good. They were friends of the devil – what could he do? He neither condoned nor damned them. If people looked to the man dubbed Captain Trips (a phrase later adopted by horror author Stephen King in his novel The Stand) for guidance, he wasn’t about to give it.

The band’s latest additions, pianist Keith Godchaux and his vocalist wife Donna, were superfans who became Dead members. If Donna was their Janis Joplin, she wasn’t always on the money, while Keith became a massive coke freak who burnt himself out and died in 1980, aged 32. Even so, they played an integral part in the next batch of studio albums that ran from Europe ’72 to Wake Of The Flood, From The Mars Hotel, Blues For Allah, Terrapin Station and Shakedown Street, which gave the lie to the notion that the Dead couldn’t cut it in the studio.

After a brief hiatus after their second Alexandra Palace dates in 1974 and so-called farewell shows at the Fillmore West and Winterland in San Francisco, documented on the critically slaughtered Steal Your Face double live set, the Dead took stock.

“Going our separate way for a while saved us,” says Weir in Long Strange Trip. “I altered my lifestyle somewhat because I figured I wouldn’t live much longer if I spent another six months on the road.”

Garcia didn’t stop playing, and formed his own band, while Weir joined the Bay Area group Kingfish. Lesh, Garcia and Hart contributed to Ned Lagin’s well-received electronic album Seastones. Hart explored his own obsessions with the Diga Rhythm Band.

In 1978 the Dead played in front of the Great Pyramid in Cairo. I met them there and interviewed them, including one memorable chat with Garcia while he was sitting on the Sphinx.

The Egypt trip was probably the last Acid Test. Kesey and Quicksilver bassist David Freiberg were in the audience, as was Owsley’s psychedelic libation, served to us via dropper bottles while the Dead played during a total eclipse of the moon.

To celebrate the event, promoter Bill Graham threw a party in the Sahara Desert (bring your own camel) and basketball legend Bill Walton scaled the Great Pyramid Of Giza and planted a Skull Fuck Dead flag on the highest point. It was beyond strange, since the Dead’s sound system was isolated through the pyramid’s King’s Chamber, while the Egyptian authorities turned a blind eye.

By 1980 the Dead’s audiences were as much part of the story as the band themselves. The Dead Heads had been around ever since Hank Harrison (father of Courtney Love) coined the phrase on the 1971 double live album Skull And Roses: ‘DEAD FREAKS UNITE: Who are you? Where are you? How are you? Send us your name and address and we’ll keep you informed. Dead Heads, P.O. Box 1065, San Rafael, California 94901.’

A decade on, the Heads settled into their own ‘zones’, with sanctioned bootleg tapers setting up camp like bird watchers. To Garcia, the Dead represented a chance for these latter-day pioneers to hop the metaphorical railroad, as his own hero Jack Kerouac had done.

“It’s all about getting your war stories, and America has become so lame. We let the tapers carry on because we’d either be cops or let ’em in, and we didn’t want to be cops. It was fine by me.”

“It was just easier,” Weir said. “We gave the music away and made money on the tickets instead.”

In any case, it didn’t kill the band – in fact it tripled their audience. Ignored by the mainstream, the Dead just grew huger and richer.

The 80s began with new keyboard player Brent Mydland replacing Keith and Donna Godchaux, and the release of the patchy Go To Heaven album, whose cover made the group look like ageing New Romantics. Kreutzmann said: “If you go back and listen to it, you’ll find it plays better now than it did back then. That’s still no excuse for the cover, though – all six of us dressed all in white disco suits, against a white background.”

He was only half-right.

Garcia seemed disillusioned with his iconic status. He was smoking a lot of heroin. In July 1986 he suffered a diabetic coma that practically killed him. In recovery he could barely walk and had forgotten how to play the guitar. His friend and fellow musician Merl Saunders remarked: “It sometimes took an hour or two for him to get even a simple chord down. Then, as we got further into it, some things started to come back to him a little, but it took a lot of work.”

The arrival of a new lyric from Hunter called Touch Of Grey helped the revival. The song became their anthem and a Top 10 hit, while the album In The Dark went platinum. Touch Of Grey’s fist-pumping chorus ‘I will survive, I will get by’ helped rescue a lost cause, and the Dead now made it on to prime-time chat show slots with Garcia and Weir on charm offensive. Hey, they weren’t so scary. More cuddly counterculture.

But the song was a blessing and a curse. As audiences doubled in size, events beyond their control turned nasty, with riots and even a death during their 1988 tour. Garcia maintained his ambivalence in the face of this rabid hero worship. “I felt it could be pernicious – I was aware of the power,” he says in Long Strange Trip. “If I thought about controlling it, it would be perilously close to fascism. I don’t want to be a king or a president.”

In July 1990, I covered the Dead in America. Garcia’s body had ballooned, but his playing could still be mercurial. Before the shows, he lay on a slab like an Egyptian mummy. Occasionally a member of the crew would peek through the dark curtains of his tomb to check that he was still breathing.

Still, he was lucid. We had dinner – “You choose the wine, you’re a sophisticated European” – and I sat in his room while he played endless scales on his beloved banjo. He swam a lot and waxed lyrical about his keep-fit regime and scuba diving.

In October 1990 the Dead made their last visit to Europe and played at Wembley Arena in time for Halloween. After the shows, Garcia sat in his Knightsbridge hotel while a rock-star dealer provided freebase coke and near-pure pink Persian smack speedballs, the very same combo that had killed keyboard player Brent Mydland three months earlier.

Clearly exhausted by touring, Garcia felt an obligation to carry on. So many mouths to feed. The Dead rallied round him, but apart from the odd rehab he didn’t stop. His daughter Trixie watched his slow demise. “He played his scales all night watching The Twilight Zone and his favourite corny old horror B-movies. I wish he would have gotten some fucking rest.”

“I’m not afraid of death, and anyway, they always love it when I don’t die,” Garcia chuckled.

In the mid-90s, the Dead were just about the most popular and powerful live draw on the planet. They were being loved to death, and the moving circus that surrounded them was uncontrollable.

Long-time Dead lyricist John Barlow saw the dilemma. “The whole point was we didn’t tell people anything,” he says. “Garcia’s stance was: ‘We are not the government, and if people take drugs, that’s a personal issue. They have the right to do what they want.’”

He certainly did. The band played their final tour with Garcia in 1995, when Weir said that “Jerry couldn’t move or go out and it drove him nuts”.

Forced into seclusion, he took more heroin. “We all thought we could help him – he wouldn’t stop,” says Lesh, who attended many a band ultimatum.

“His heroin abuse made him testy, but the show had to go on,” said Cutler.

There was a half-hearted effort to make an album. The previous record, Built To Last, was commercially successful and artistically moribund.

New sessions began in 1992, but Garcia lacked the impetus to finish them off. At his final show with the Dead, at Soldier Field in Chicago on July 9, 1995, one observer noted: “He seemed distracted much of the time. Aside from the moments when he was in the zone and losing himself in the music, Jerry looked like he really just wanted to go home and forget all this.”

Garcia’s death – in his sleep, on August 9, 1995, at a rehabilitation clinic in Forest Knolls, California – occurred a week after he turned 53. He’d given up heroin and become vegetarian, but it was too little too late. As Weir said: “He was pressing a bit harder, I think, than his body could keep up with.”

In Long Strange Trip, Hart says just “He killed himself.” Cutler says “he was suffering,” Barlow that “he’d had enough”.

Fans were stunned. They flocked to Golden Gate Park in San Francisco and held vigils. Garcia’s death resonated like John Lennon’s. Rolling Stone published a memorial issue, and In The Dark went double platinum.

Garcia might not have approved. “I’d rather have my immortality here while I’m alive,” he said in 1993. “I don’t care if it lasts beyond me at all. I’d just as soon it didn’t.”

His ashes were thrown into the Ganges and the San Francisco Bay.

Today the 69-year-old Weir still takes a group called Dead & Company on the road, with Kreutzmann and Hart joined by guitarist John Mayer. Dead releases continue to flow: their remastered ’67 debut, a classic set from Cornell University in ’77 and the Long Strange Trip soundtrack are recent examples. There’s plenty for Weir to get stuck into.

“I still feel Garcia’s presence on stage so, weirdly, I don’t miss him then,” he says. “Later I do miss the amusement, the shared comedy and the music. Personally I don’t mind ageing, because experience is wonderful. I feel young enough and I’m not going to retire.”

Dead & Company stick to the old two-set template, but they don’t hit the three-hour mark any more.

“The overall arc is what Jerry and I developed together over forty years,” Weir continues. “We were fairly predictable. The first set begins and ends with something anthemic or mildly huge, and then we venture off. It’s paced like an opera, with the big aria and the denouement. Trial and error, really, but it worked for us.”

He doesn’t pay much attention to the constant reissue programme, either.

“That era, the Summer Of Love, means an accumulation of things. It was exciting but also a bit disappointing because 1966 was really the Summer Of Love. There was the impetus and we were fresh and facing a world of possibilities. All the things the press talked about, we’d already explored. They’d happened ,and then people descended and it was too late.

“People came to the Bay Area to participate, but an awful lot of riffraff came to join the party. In sixty-six, Haight-Ashbury was a youth ghetto of students, artists and free-thinking folks. It was an authentic community. By sixty-seven it became alien once every loose nut and bolt rattled to the coast. There was the hippie scene, but when the hard drugs arrived so did the crime.”

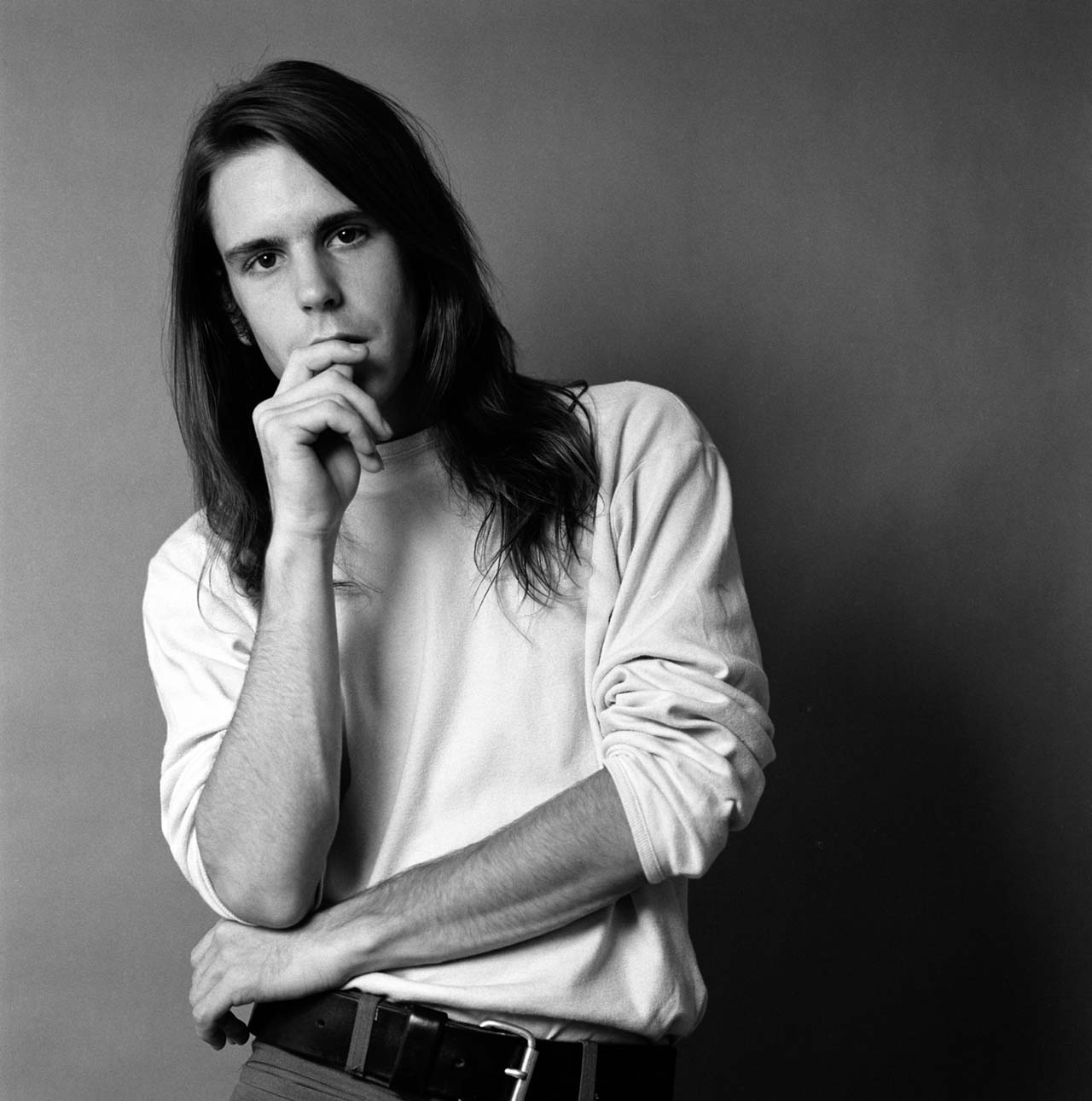

Weir, now whiskery and sage-like, was the poster boy for the Dead. Women loved him and he loved them back. “I pretty much thought I was a hippie, or that we were a lot hipper than the society making war with another country [Vietnam] they didn’t even understand,” he reflects. “Looking back, I feel I had a wonderful and amazing job. I was laughing for joy. We were making a pretty good living, and beyond that the possibilities were enormous. We didn’t get to all the places we wanted to and we didn’t change the world, but we were doing stuff that mattered, and we knew it.”

Weir compares that era to “the years before and after the American Revolution and the drafting of the constitution: the assembling of a brand new culture built entirely on idealism. We did have roots. The songs we grew up on came from a tradition with history – Scottish ballads, medieval folk, they morphed in. When I sing that type of song, I really find the voice of those folks. The scenery is different. I don’t want to sound visionary, but there are moments when I feel like I’m back in time and everything changes colour. It’s another world.”

Recently he completed his third solo album, Blue Mountain, with lyricist Josh Ritter, cowboy songs inspired by Weir’s time as a ranch hand. “When I was fifteen I ran away to be a cowboy. I found myself working in Wyoming, living in a bunkhouse with a bunch of old cowpokes and ranch hands, and a lot of those guys had grown up in an era before radio had even got to Wyoming. Their idea of an evening was to tell stories and sing songs. I was the kid with the guitar. I was the accompaniment. I learned a bunch of those songs and got steeped in that tradition. It’s a tradition that’s almost gone.”

It’s possible this may be the last Dead-related studio album. They were never that keen on the recording process.

“Our problem was we played too loud because of our live experiences. The notion was we should make better, more acceptable records, so we entrusted producers. And it didn’t always work.”

Perhaps the most frustrating Dead album is 1978’s Shakedown Street, which Little Feat’s Lowell George began producing but didn’t finish. “He did as good a job as anyone, but there was far too much chemical adventure and far too much drinking: Peruvian marching powder and brandy. It certainly wasn’t good for Lowell, cos the cocaine turned his heart off and that was that. He had a lot of anxiety problems. He was very nervous around the Dead and he had to flush a lot of demons out just to keep in check.”

So how does Bob Weir sum up the Grateful Dead now?

“Jerry had a role. I had a role. Mine was to pull everything together and focus to a point where Garcia could dance with it. I was the glue. And that’s a great job to have because when it works, the band sits up and begs.”

As for the future, who knows? Phil Lesh is still out on the road, despite having suffered two bouts of cancer. Weir will join him in August.

“I guess while we can still crawl out there, we will. The music won’t stop until we do. It’s a case of last man standing.”

Long Strange Trip: The Untold Story Of The Grateful Dead is available via Amazon. Stream now on Prime Video