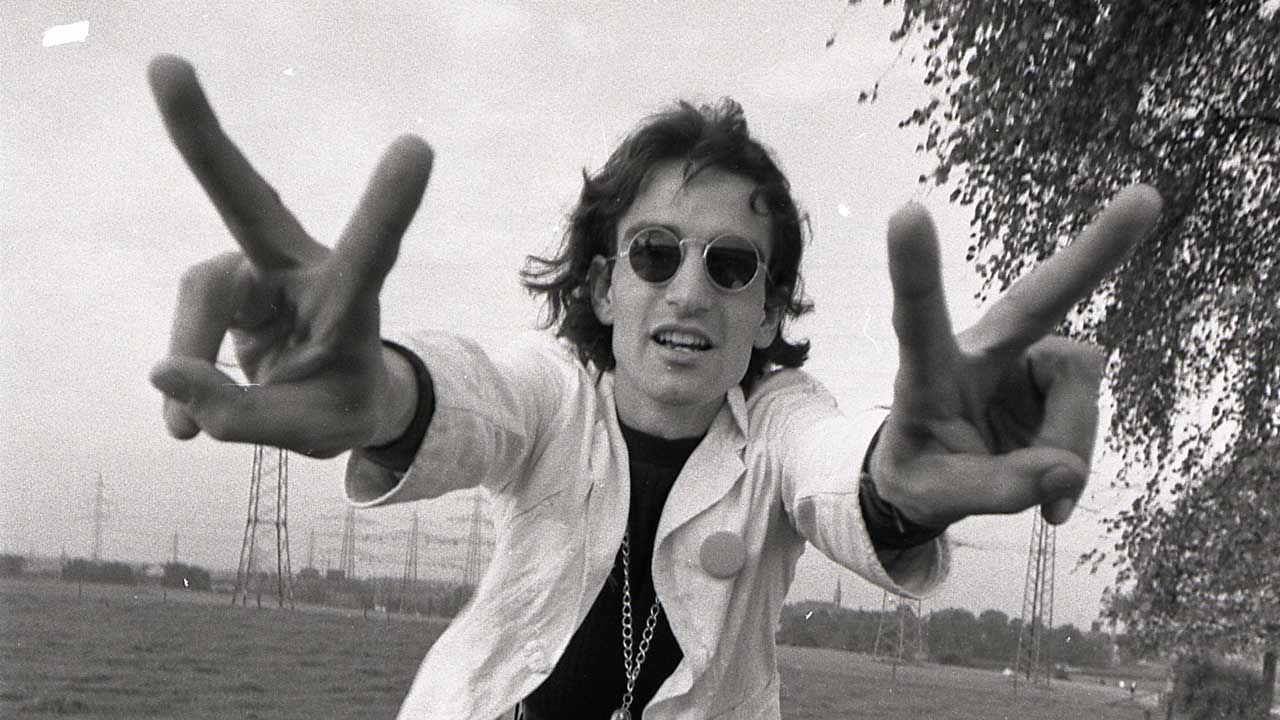

In his marijuana-marinated mind, New York street singer David Peel was simply claiming his rightful title when he declared himself King Of Punk in 1978’s song and album of the same name. All he had to do was upgrade the subversive rants he had been howling in the parks of Lower Manhattan since the mid-60s by deploying swarms of electric guitars and expand his usual smorgasbord of getting stoned, police brutality and his brief friendship with John Lennon to confirm his godfather status in the city’s punk heritage.

Listening now to the recently reissued King Of Punk is like stumbling on an old blues field recording by Alan Lomax. Determinedly low-fi and accompanied by squalling banks of angry guitars (but no drums), Peel amps the stoner howl he had been using since the mid-60s into a sneering double-tracked monotone which almost sounds like punk parody as he reels off his hit-list like a gnarly, self-aggrandising answer to Wayne County’s Max’s Kansas City; “Fuck Patti Smith…Fuck the Ramones…Fuck Sex Pistols…Fuck Talking Heads…Fuck the Heartbreakers,” etc.

Using the same street smarts which had got him into close to Lennon six years earlier, Peel felt he had a right to claim his piece of the downtown action because he was blazing similar raucous trails before a club called CBGB or band called the Ramones were even dreamed of. If punk was about hurling Molotov cocktail messages at the mainstream over rudimentary DIY backdrops, Brooklyn-born Peel had been doing that since forsaking a potential job on Wall Street in favour of becoming a hippie in the mid-60s, soaking up the vibes in San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury before taking his stoner street activist ethos to Washington Square Park. (At this point it should be pointed out that, apart from the more dullard factions, punk was essentially propagated by hippies with shorter hair).

For decades, the park had been the gateway to Greenwich Village’s vibrant artistic hub, playing host to folk gatherings since the Second World War, welcoming Bob Dylan off the bus in 1961 and giving a platform or simply some conscious entertainment to thousands more. Peel arrived in the mid-60s as another manifestation of the punk attitude which had charged New York’s shape-shifting artistic movements since the Beat Poets sprang up alongside bebop, subsequently joined by activist folk and, most recently, Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground.

But in terms of confrontational impact, nothing topped the notorious Fugs, who appeared in the East Village in 1965 as New York’s founding fathers of agit-punk protest, noisily expounding about the joys of drugs and sex over makeshift percussive backdrops, before morphing into an electric rock band railing against the Vietnam war in 1966. They were also the first to use the word “punk” on record.

As Peel recalled in 2016, “I joined the hippie movement during the middle 60s in Greenwich Village and played guitar with all the other musicians and folkies, and became part of the ‘out crowd’ having fun. New York then was pretty straight looking and leaned more towards jazz and folk music, but the Fugs were the first band in the East Village to erupt into counterculture underground rock. It was the first time I saw a music group play uncensored music. Wow!”

Peel took the Fugs’ taboo-shattering street chant ethos to Washington Square’s gatherings which, by 1967’s “summer of love”, included love-ins but were increasingly being infiltrated by politically vociferous elements incensed by the escalating carnage in Vietnam and intent on causing as much havoc and social unrest as possible.

By 1968, these included Abbey Hoffman’s Yippies and the more insurrectionary Up Against The Wall, Motherfuckers, a bunch of disruptive East Village rebels mobilised by painter Ben Morea because they considered Yippies too lightweight. That March, the UATWM gatecrashed 3000 Yippies sitting in at Grand Central Station, where Peel made his presence felt by leading the singalong of I Like Marijuana which became Have A Marijuana after being misquoted in Time magazine. Soon it would provide the title of his first album.

Even if Peel could seem more Fabulous Furry Freak Brother than Street Fighting Man, he captivated the crowds in the park, including the future Joey Ramone and his brother Mickey, who sometimes joined in the songs, and a passing Danny Fields one afternoon in March 1968. Fields, who had been editing teen magazines and was part of Warhol’s circle, had joined Jac Holzman’s venerable Elektra Records as a publicist and resident “freak on the street”.

Since being started in 1950, Elektra had released a huge array of mainly folk, world music and sound effects albums but, by 1968, was at the forefront of the psychedelic revolution with The Doors, Love and Tim Buckley. That summer would see Fields catalyse the nascent punk movement by signing the MC5 and Stooges to the label but, already sensing revolution in the air, he was gripped by Peel’s energised drug busker missives and took him to Max’s Kansas City, at that time the prime local artists’ hot-spot, winning his trust and signature on a contract by letting him loose on the steak menu.

Curiously Elektra, this bastion of the folk movement, had never recorded an album live at Washington Square, so engineer Peter Siegel was dispatched to capture Peel and his gaggle of like-minded stoners who called themselves the Lower East Side, bellowing over guitars, harmonica and basic percussion to create the Have A Marijuana album (although the sleeve said “recorded live on the streets of New York” for extra cred).

Although Peel escaped being sent to Vietnam because he had already done his national service, the opening track was Mother, Where Is My Father?, a cutting indictment of the escalating war. Normal service was established on ditties such as Show Me The Way To Get Stoned, Here Comes A Cop and I Do My Bawling In The Bathroom. Sometimes it sounds like a musical version of a stoner cartoon, as the group shout, giggle and warble their messages through tangible clouds of marijuana smoke, but Up Against The Wall, Motherfucker highlighted the revolutionary slogan and marked first use of the M-word on record, while I’m Going To Start a Riot presaged The Clash (who later admitted it was an influence).

Although psychotic cops are never anything to laugh about, Peel was like a stoned cheerleader in the prevailing atmosphere of civil disobedience, whose demonstrations were part of an ongoing civil war, as counterculture fought culture. As a document of the times, the album can be seen like a more goofy forerunner of the Last Poets’ much darker and dangerous Harlem equivalent. It’s almost unbelievable that such an anarchic set was given the backing of a major record company and made 186 in the national top 200.

Peel also opened the legendary gig at New York Pavilion in Flushing Meadows, Queens in September 1969, which also included the Stooges and MC5 (and so influenced local artist Alan Vega he decided to start performing, which resulted in the formation of Suicide). Recalled Peel, “I was a just a street rock musician, underground activist and protester against the Vietnam war, defending civil rights, pro-marijuana and beyond. The gig was typical of the time, performed with the MC5, the Stooges and my band. Danny Fields got us the gig to promote all three acts on Elektra.”

Peel and the gang’s next move was to venture into the studio for the first time to record their second Elektra album, The American Revolution, which depicted them in suitable apparel on the sleeve. With a more streamlined sound, the album can be seen as a direct precursor of and influence on upcoming outfits such as the New York Dolls, Dictators and Ramones. Although the album seemed to appear as revolutionary statement, mirroring the mood of a country still mourning events such as the student massacre at Kent State University, Peel described it in his customary convoluted stoner-speak as “just another recording to extend my music lifestyle as a continuous means of songs I made as a counter-culture activist, which Elektra allowed me to do without censorship.”

The following year, John Lennon and Yoko Ono caught Peel in action in the park, after he had approached them in a Greenwich Village clothing store and introduced himself with his customary hustler’s patter. After local writer Howard Smith brought John and Yoko to a Washington Square Peel hoedown, a relationship was formed as the three, plus Yippies Abbey Hoffman and Jerry Rubin strolled around the Village singing Have A Marijuana. “John and Yoko liked what they heard and saw, and asked me over to their apartment on Bank Street in the West Village,” recalled Peel. “They said they would like to produce an album on Apple Records and I said ‘yes’.”

Lennon embraced Peel as a conscious heartbeat of the city he would soon adopt as home, declaring “Yoko and I love his music, his spirit and his philosophy of the street.” Lennon, Yoko and Peel appeared at the Free John Sinclair Rally held at the University of Michigan’s arena (a few days before the former MC5 manager was released after being sent down for possessing two joints).

By then, Peel had been dropped from Elektra and operating his own Rock Liberation Front operation with creepy Dylan stalker AJ Weberman. The pair declared that RLF’s aim was to instil unity and fun in rock, while protesting at Led Zeppelin commanding $75,000 a gig and the lame quality of Ram, Paul McCartney’s latest solo album. After being approached by Peel, John Lennon became a supporter of RLF, saying he wanted to give away his material wealth and expressing fervent desires to do something political. He signed Peel to Apple and, with Yoko, produced the album which became The Pope Smokes Dope, complete with ditties such as Everybody’s Smoking Marijuana, The Hippies From New York City and I’m Gonna Start Another Riot. The album promptly got banned all over the world.

After the Lennon episode fizzled, Peel went on to start his own Orange label (in homage to Apple), which released variations on his themes including 1974’s Santa Claus - Rooftop Junkie and 1976’s An Evening With David Peel. He also released an album devoted to getting the Beatles to reform, which opened with The Beatles’ Pledge Of Allegiance and included him interviewing Lennon.

By now, another movement had started bursting from the bowels of downtown Manhattan, starting with the first steps taken by the New York Dolls at the Mercer Arts Center then turning into the giant footprints left by the Ramones and usual suspects at CBGBs and Max’s, which coalesced into downtown’s punk explosion. As Peel put it, “These music scenes were in my East Village neighbourhood; a new happening which was a lifestyle type of music that I did on the streets and at local venues. Joey Ramone and his brother Mickey Leigh used to hang out and sometimes perform with me in Washington Square when they were teenagers. As Mickey has often mentioned to me, it was sewing seeds for the punk rock movement. Hey ho, let’s go!”

In 1978, Peel released King Of Punk. The title track was one of the first punk “beef” records, spitting a succinct “Fuck” at the new bands and recently deceased Sex Pistols. The album also explores Peel’s perennial themes of CIA mind control on The Master Race, Uptight Manhattan, the jaunty He’s Called A Cop and, of course, Marijuana. “It just organically happened as part of my living and singing in the East and West Villages,” explained Peel. “Punk rock was another form of rebellion and counterculture music style expression that began at CBGB. My punk music began on the streets. As I always say, punk rock forever!”

The album’s most intriguing detour comes in the form of the 11-minute Who Killed Brian?, which addresses the Stones founder’s controversial death, (heisting Strawberry Fields Forever on the chorus). “I really don’t know, but I have a suspicion that Brian’s music and personality and the Rolling Stones as a band was just too much for him to handle,” reasoned Peel. “But Brian may have been killed by one of his employees drowning him in his swimming pool. My song is a metaphor about his death after he was persuaded to leave the Rolling Stones because of his lifestyle and behaviour, leaving the rest of the Stones in control of the band’s music and performance direction.”

Further albums followed, including a predictable harangue against disco called Death To Disco, John Lennon For President, 1984’s 1984, World War III, Anarchy In New York City, Battle For New York and War And Anarchy. After 1995’s “comeback single” Junk Rock he again stated the obvious with Legalize Marijuana.

In 2002, Peel was declaring himself a Rock And Roll Outlaw but, by then, had another major topic to beef about as his Lower Manhattan stamping ground became systematically smothered and its artistic spirit snuffed out by the yuppie gentrification juggernaut. In 2011, he joined thousands in the Occupy Wall Street movement, recalling, “Me and my music friends performed there and made a record as David Peel and the Protesters called Up Against The Wall Street.”

In his final years – Peel died in 2017 after suffering a series of heart attacks – his beloved New York inexorably turned into a vastly different, greed-propelled city. But Peel seemed as ancient, venerable and immortal as the trees that had stood in Washington Square Park since it was a burial ground for the city’s unknown poor: a loud vestige of his city’s wild, exciting past, still railing and kicking against the pricks.

"Punk rock forever," he proclaimed. "Forever punk rock!”