Don’t forget to vote at the bottom of the page, but we suggest you first pay attention to the trainers in this week’s bout. There’s Paul Lester, who’ll be in the corner for Phil Collins, but to start the action, pulling on the gloves for Peter Gabriel, it’s Chris Roberts. Seconds out, round one…

OK, so Phil Collins might have saved Genesis and become one of only three artists in history (along with Paul McCartney and Michael Jackson) to have sold a hundred million albums both as solo artist and (separately) as a band member, but has he walked onstage in a red frock and a fox’s head? Has he made four solo albums with the same name? Has he invented both world music and digital music distribution (ahem), scored a Scorsese film and been Oscar-nominated for singing on the soundtrack of Babe: Pig In The City? Has he dated Rosanna Arquette and hugged Kate Bush for the duration of a video? Has he singlehandedly brought down apartheid, worked with Nelson Mandela and been named by Time magazine as one of the world’s most influential people? Has he performed at the Brandenburg Gate to mark the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, which probably only fell because of him (and maybe David Hasselhoff) in the first place? Has he inspired the character Brian Pern?

But seriously… as Phil might say. While it’s a popular misconception that Collins turned Genesis commercial (he, Rutherford and Banks were a fairly democratic trio), it was Peter Gabriel who initially turned them good. His onstage personae, costumes and lyrical kinks gave colour and character to ambitious music which might otherwise have wafted away on a cloud of directionless pomp. It was Gabriel who, on the peerless Supper’s Ready, sang: “There’s Winston Churchill dressed in drag, he used to be a British flag, plastic bag, what a drag. The frog was a prince, the prince was a brick, the brick was an egg, the egg was a bird.” Who among us can honestly deny that those words speak to our innermost psyche, capturing the very essence of the eternal human condition?

Upon leaving Genesis in 1975, around the time of The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway, which was a double album about consumerism and chronic masturbation in New York City, Gabriel hand-delivered an entertaining open letter to the UK music press. (It’s almost as if they didn’t have email then). He asserted that he was not going to “do a Bowie”, “do a Ferry”, wrap a “feather boa around my neck and hang myself with it” or “go senile in the sticks”. “Much of my psyche’s ambitions as “Gabriel archetypal rock star” have been fulfilled,” he added, “a lot of the ego-gratification and the need to attract young ladies, perhaps the result of frequent rejection as “Gabriel acne-struck public school boy”. However, I can still get off on playing the star game once in a while. My future within music, if it exists, will be in as many situations as possible.”

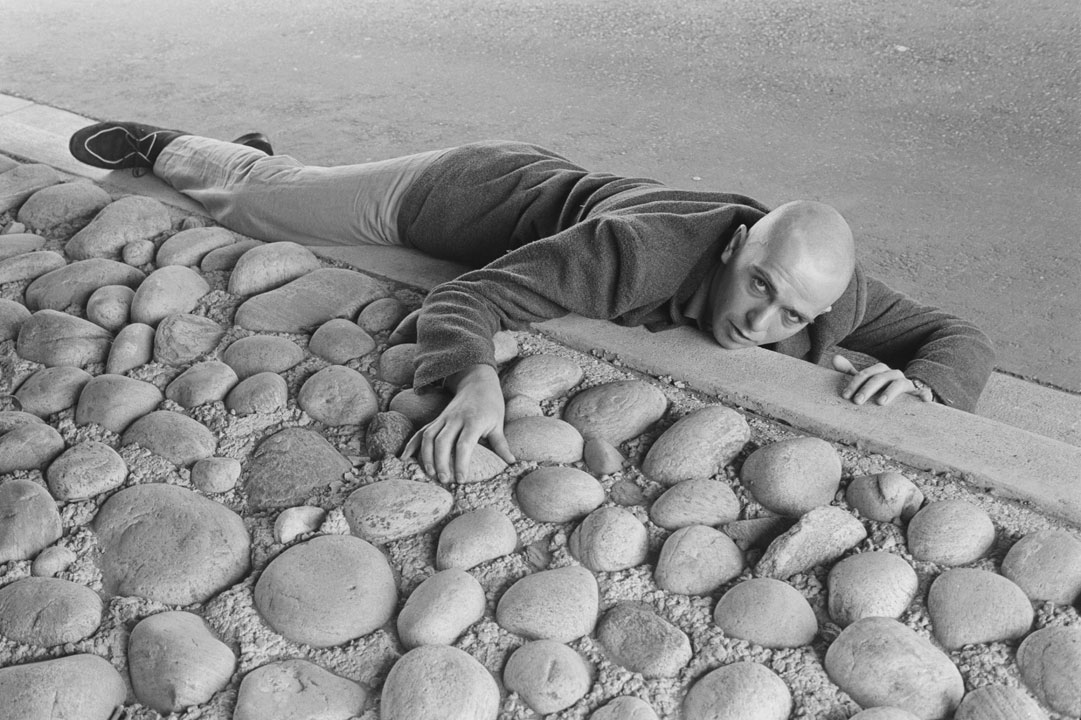

These situations saw him forsaking tendencies to shave a badger stripe down his head or wear batwings, or dress up as Britannia or as a forlorn old man decorated with a collection of rubber phalluses. As a solo star, he streamlined. While Phil’s Genesis were dicking around playing a rainy Milton Keynes Bowl in 1982, simply to kindly bail out the impecuniousness Peter had brought upon himself with WOMAD, he was exploring brave new territory. No longer did he have to entertain the crowd with Ossie Clark dresses while the band tuned up their 379-string guitars. Embracing the New Wave of stuff in general, a leaner, keener Gabriel delivered four thrilling solo albums, which were called Car, Scratch, Melt and Security, at least by people who couldn’t grasp that calling all the albums the same thing was artistic genius. Hits like Solsbury Hill, Games Without Frontiers and Biko established him as cooler than Phil, but by the fourth album he felt secure enough to bring back elaborate stage props, hanging from gantries mid-show and distorting his features with mirrors and lenses. Phil’s starker aesthetic of a simple paint pot just could not compete with this.

As the Eighties became “the MTV Eighties”, Gabriel – like Collins - reached his peak of popularity. Yet while the latter was singing about obscure, esoteric stuff like love and heartbreak, Gabriel – on the multi-platinum So – was stating that sex was a sledgehammer, via the most award-winning video of all time. In fact, Sledgehammer knocked New Genesis’s Invisible Touch off the top of the US charts. “Take that, Buster!” Gabriel didn’t snarl.

Moving now from triumph to triumph, Gabriel prestigiously scored The Last Temptation Of Christ. Contrast this against Collins’ Against All Odds (Take A Look At Me Now), which, when Oscar-nominated, couldn’t even beat some guy called Stevie Wonder. In fact, Collins didn’t win an Oscar until 1999, by which time Gabriel had made a video (Digging In The Dirt) featuring himself covered in snails. He then delivered a soundtrack for the Millennium Dome Show of 2000 and has in more recent times released an album of covers with an accompanying 3D movie and toured to mark the So album’s 25th anniversary. His Real World studio has recorded everyone from Jay-Z and Beyonce to Weird Al Yankovic.

He has stayed on the cutting edge of advances in technology, conversed with astronauts in space, and as an activist for humanitarian causes has proven tireless. Now Collins has also done charitable works in his time, but consider this: has he ever, as Gabriel did in 2001, taken part in jam sessions with Congolese bonobo apes at Georgia State University? He has not. Or if he has, he’s kept it to himself. For all Phil’s tenderly-sung “adult contemporary” classics, mad skills on the drums and wealth of knowledge about the Battle of the Alamo, Peter Gabriel has shown – whether through his combating climate change or his innovative work with plasticine – that in the garden of imaginary Genesis smackdowns, he’s the lawnmower.

Collins is on the canvas. Can he rise again? Paul Lester certainly thinks so…

Hey, guess what? I’m PC: Pro-Collins. Not many rock writers will admit that. He’s been the butt of music press jokes for years, even decades. The times journalists have picked up the phone - at the NME or Melody Maker - only to find Phil Collins at the other end of the line, demanding to know why they were so mean about his latest album, are legendary. Because he cares, and those throwaway barbs sting. Julie Burchill used to base her loathing of him on the fact that, as she saw it, he was the only man she knew whose face permanently looked as though he was wearing a robber’s stocking mask. Can you imagine how that felt? No amount of money could take away that pain. Well, maybe a bit.

When I met Collins, for an interview with Prog, near his home in Switzerland in 2010, he was a severely reduced figure - and he was never a tall man to start with. Seriously, though: the years (decades) of criticism finally seemed to have got to him. He was pale, withdrawn, far from the avuncular über-geezer of lore. To look at him, to see him hunched in the shadows of the small hotel room where the encounter took place, you’d be hard pressed to believe that this was the most successful pop artist of all time, with the exceptions of Michael Jackson and Paul McCartney.

I’m not saying you can base your appreciation of a musician on their success, but it is hard to argue with statistics like these: Collins, if you add together his sales with Genesis (100 million) and his solo sales (150 million), is commercially outflanked by only the aforementioned Macca and Jacko. And he can’t even boast a cuddly diminutive like theirs. No one, for example, calls him Collo. They should.

Actually, it’s that blokeiness, that sheer affability, that winds people up, as though it’s somehow a crime to be friendly. They prefer the arty inscrutability of Peter Gabriel, Gabriel’s offhandedness, his enigmatic detachment from the fray. Gabriel is the sort of individual you might see askance at a gallery or museum. Collins you’re more likely to catch down the pub.

I say people don’t like him, when really I mean critics. Proper human beings love him - hence the enormous sales. So do rappers and R&B types - hence the Urban Renewal tribute album from 2001, featuring Ol’ Dirty Bastard, Lil’ Kim, Montell Jordan, Kelis and others performing cover versions of his hits. I’d rather have Ol’ Dirty Bastard in my corner than a bunch of spotty hacks. Right, readers?

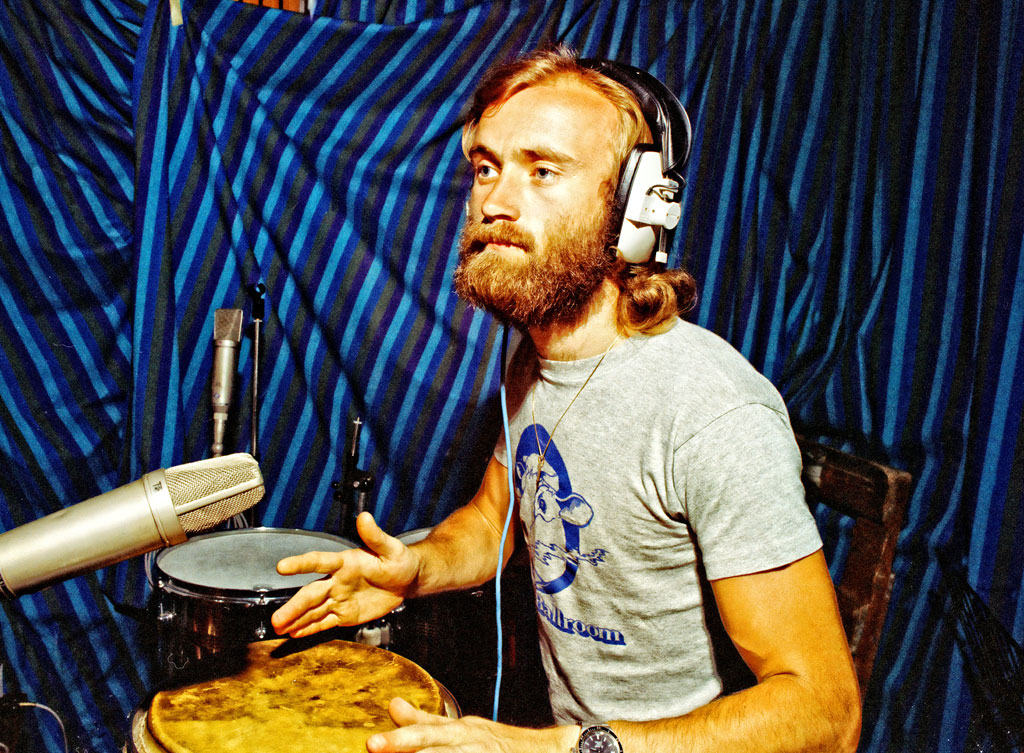

The question you’ve got to ask yourself is: why do Dirty (RIP) and Co rate Collins? Because he’s good, that’s why. Really good. He’s a brilliant drummer. He writes a mean pop song. His she-done-me-wrong ballads are second to none. His jazz-rock chops are impeccable. And, contrary to popular opinion, he is not averse to constructing a tripartite song-suite.

Few musicians have his credentials (will you get over Live Aid already?). Gabriel’s Games Without Frontiers was a superb dub-spacious tune that managed to inveigle its way up the charts? Ditto In The Air Tonight, an all-time classic of the haunting pop song genus which also happens to possess the most famous drum break in chart history. Genesis with Collins out front were more readily melodic, yes. But anyone who says they didn’t do powerfully plangent music with him at the helm should be made to listen to Ripples for all eternity - it’s a staggering work of heartbreaking poignancy.

Genesis under Collins’ tutelage still did long epic songs full of complexity, intricacy, tempo shiftery, all that malarkey. It’s all there on Trick Of The Tail, where most of the tracks are between six and eight minutes long. Have you heard the multi-section One For The Vine from Wind & Wuthering lately? How about Wot Gorilla?, all dexterous neo-classical bursts and funk-jazz fusion. Or Blood On The Rooftops, a song known to reduce even the most hardened of Collins-watchers to tears? By Duke, for sure, there was a definite pop sensibility at work - but then, that was true of Pink Floyd and Yes and all the other prog behemoths. They were all forced to streamline their acts for the new era, so the keyboard colossi could keep up with the synth kids. You can tell on Abacab they are influenced by Talking Heads and Eno - and Gabriel. But why not? Credit to Collins for being open to the cool sounds du jour. What did you want? For Genesis to stick their heads in the sand and become irrelevant dinosaurs like so many of their peers? Did you notice ELP selling many records in the ‘80s? Exactly. They did fuck-all. Genesis could easily have become similarly redundant. I would argue - with a pint in my hand and a bag of crisps at the ready - that it was Collins who singlehandedly saved them from obscurity following the departure of Gabriel.

He was Seventies Man and then he went and became the biggest star of the Eighties, with more hits than Springsteen, Jackson and Madonna. He mastered the bombastic brass construction and neo-Motown soul-pop. And on Sussudio he outdid Prince at his own funk game.

By the mid-‘80s it’s hard to tell Collins’ solo material apart from Genesis’s albums of the same period - but you could also include Gabriel solo in that judgment (notice, too, how, as time goes on Collins and former pretty-boy Gabriel start to resemble each other, both baldie brothers in arms). It’s as though they shared a musical DNA and whatever they did had “that” sound: big, polished, with crashing cymbals and gated drums. It was a sound that reached out to the masses. It’s just that Collins’ masses were more, um, populous than Gabriel’s.

Truth is, his music is warmer than Gabriel’s, with the possible exception of So. It has what you might call the common touch. It connects musically - obviously - but also emotionally. His records might not be as intellectually satisfying as Gabriel’s, but they’re more likely to move you on a visceral level. They are - what’s the word I’m searching for? - better, just as Collins is better than Gabriel. A quarter of a billion people - and a music journalist wearing a robber’s stocking in sympathy - can’t be wrong.

LAST WEEK: TONY IOMMI VS JIMMY PAGE

Results: Tony Iommi: 57% Jimmy Page: 43%