The Freilichtbühne Loreley is one of the world’s great venues. Perched high on the Loreley, a 400-foot rock overlooking the Rhine Gorge in Western Germany, this open-air amphitheatre was originally built by the Nazis as a Thingplatz – a showcase venue for the Third Reich to stage displays of propaganda thinly disguised as drama.

Other, older myths surround the Loreley. According to local folklore, it was the home of a siren who would draw passing ships onto the rocks more than 400 feet below. This macabre legend has been referenced in music by everyone from German composer Felix Mendelssohn to Wishbone Ash.

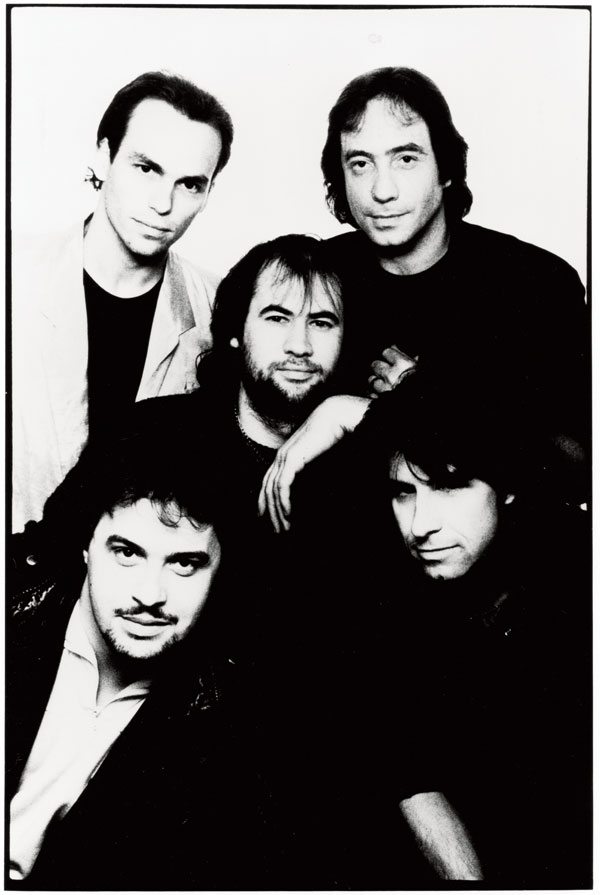

On July 18, 1987, Marillion arrived at the Loreley to play one of the biggest headlining shows of their career yet. It was two years since the release of Misplaced Childhood, the album that turned this unfashionable prog band into the unlikeliest pop stars of the decade.

But success had brought unforeseen issues. The demands of constant touring were taking their toll, and the gang mentality that originally fuelled them was fracturing. This turbulence was captured on the band’s most recent album, Clutching At Straws, a snapshot of a band struggling to keep their heads above water. In its central character, Torch, frontman Fish laid his own inner turmoil bare.

The 20,000 fans gathered at Loreley to see them might not have been aware, but Marillion were under a dark cloud. Behind the scenes, the band had split into two camps: Fish on one side, the rest of his bandmates on the other.

“Things were very miserable,” says guitarist Steve Rothery today. “If you watch the Live From Loreley video, you can see the mood. The unity had gone. You can blame many things, you can point the finger at people who were hanging round and aggravating the problem, whispering in ears. But whatever the reason, it reached critical mass. There was something fundamentally wrong with how things were.”

Their career wasn’t dashed on the rocks at Loreley, but they were listing badly. Within 18 months, the Fish era had come crashing to an acrimonious end, leaving the wreckage of broken friendships in its wake. At the heart of it all was Clutching At Straws – Marillion’s dark masterpiece.

“Clutching At Straws is a brilliant album,” says Fish. “I prefer it to Misplaced Childhood. It’s very honest, very open, to the point where you go, ‘Fucking hell…’”

“I feel less warm towards that album than I do Misplaced Childhood,” says keyboard player Mark Kelly. “But I know some people really like it.”

“It’s a strange album, Clutching,” says Rothery. “It’s a very powerful album in that it’s got some of our best work. But you can also see the fracture lines.”

The retrospective view of their fourth album is one of the few things the men who made it disagree on – remarkable, given the circumstances that surrounded it and the eventual outcome. On most other points, they’re in surprising accordance, albeit with markedly different individual perspectives. Certainly, all five members put the root of their problems down to the incessant touring schedule imposed on them by their manager, John Arnison.

“Just when you thought it was coming to an end, there’d be another fucking series of gigs,” says Fish. “We were squeezing the pips dry on Misplaced. It was like being at the circus. It’s all fucking singing and dancing, but when you walk outside the tent, it’s scabby animals and shite. I was physically and mentally exhausted a lot of the time.”

“I think Fish probably felt the pressure more than anyone else,” says bassist Peter Trewavas. “If you’re the person everybody wants to talk to, then the demands on your time are so great. Maybe we could have been a bit more understanding about that. But when things are happening, it’s like a fairground ride.”

The singer admits that he was partying hard, partly as a release from the seemingly endless grind. His exploits were seized on with glee by the press, who liked their rock stars larger than life and, preferably, always ready with an open wallet.

“There were a lot of shadowy people around us and a lot of fucking drugs on offer, let’s be open and honest about it,” says Fish. “People go out on tour, they get tired and worn down, they need something to pep them up for the show. Then suddenly you’ve finished the show and you’re still getting pepped up. You’re in an eternal overdraft of energy.”

It was this hedonistic lifestyle that prompted the singer to create the character who sat at the centre of Clutching At Straws. Torch was supposedly a writer suffering from writer’s block, an older, more disillusioned version of the Jester from Marillion’s earlier album. At 29, he was the same age as the man who conceived him. It didn’t take a psychologist to work out that Torch, like the Jester and the kid from Misplaced Childhood, was essentially Fish himself.

“I created the Torch character as a kind of alter ego,” he admits. “I think it was to disguise some of the excess in the lyrics that I was talking about. Because I felt guilty.”

The band needed a holiday, but the break that could have eased their situation and reset increasingly strained relationships never materialised. Instead, the band were bundled back into the studio to record a follow-up to Misplaced Childhood. EMI wanted another hit album in short order.

“The touring really did take it out of us,” says drummer Ian Mosley. “Then reality hit us when it came down to writing another album. You’ve got a blank canvas in front of you and the record company is going, ‘Is it ready yet?’”

“Now we were in the Premier League the label didn’t want us to turn into fucking Leicester City,” says Fish.

The band began sketching out rough ideas for their fourth album at Steve Rothery’s house in Wendover. Peter Trewavas remembers sketching out the beginnings of opening track Hotel Hobbies – “the soundscapey bit” he says – before the label paid for the band to decamp at a rehearsal studio between London and Brighton.

“They wanted to get us away from the clubs and bars and dark influences,” says Fish. “Everybody went down there, we were going to be good little boys and concentrate on writing an album. And it was just awful. People were getting tetchy.”

Marillion’s traditional approach to songwriting involved building up segments of songs which they would then find a way of piecing together like a jigsaw. Or, in Fish’s words, “Trying to put them together with a hammer.”

“It was a bit like Misplaced Childhood Part 2,” agrees Steve Rothery. “We were trying to stick all these tracks together that didn’t really belong together. We had to step back a bit and re-evaluate what we were doing.”

This much became clear when Chris Kimsey, who had produced Misplaced Childhood and would work on the new album, arrived with the band’s A&R man, Hugh Stanley-Clarke, to hear what the band had written. The pair were unimpressed.

“They were, like, ‘Is that all you’ve managed to come up with?’” says Fish. “Chris said, ‘I don’t hear any fucking singles in there.’”

There was one song that did stand out. It had emerged from one of the band’s sporadic post-pub jam sessions and was powered by a catchy Mark Kelly keyboard riff (“What we called ‘The widdly-widdly synth stuff,’” he says). The song would eventually be titled Incommunicado. But, according to Fish, the rest of the band were dismissive of it.

“I always loved The Who, and I wanted to do more rocky stuff, but the band were not into the idea,” says Fish. “And they were not into Incommunicado. But we played it to Chris Kimsey and he said, ‘That’s it – that’s the single.’ I was really chuffed. I felt like I got a backing for what I wanted to do.”

This split in opinion over Incommunicado didn’t augur well for Marillion’s future. It wasn’t the only point of difference either. Steve Rothery had brought in a song he’d been working on that the band thought had a lot of potential. Fish supplied a set of vivid lyrics inspired by observations he’d had while drinking one night in a pub near his parents’ house in North Berwick. The song was titled Warm Wet Circles. But not everyone was impressed.

“I liked the music, but I hated the fact that it was called Warm Wet Circles,” says Mark Kelly. “We weren’t chasing hit singles, but if you want to kill a song stone dead, call it Warm Wet Circles. Fish’s attitude was a bit like, ‘Fuck you, I’m going to do what I want.’”

Musically, Marillion had largely jettisoned the more traditional prog elements of their sound. The ornate musicality of Grendel and The Web was a distant memory, replaced by a more mature approach that wouldn’t upset the daytime radio listeners who had bought Kayleigh in their droves. But lyrically, Clutching At Straws disappeared down an altogether bleaker rabbit hole.

“It’s a lot less optimistic an album,” says guitarist Steve Rothery. “Some of it symbolises Fish’s disillusionment – he wanted success and he got success, but it didn’t bring him the personal happiness that I think he expected it to.”

“It’s a ‘drunken poet’ album,” says Fish. “That’s why the cover featured Burns and Kerouac and Truman Capote. All those people were people who had a strong association with alcohol.”

Booze soaked deep into the pores of Clutching At Straws, from the whisky-and-shattered-dreams anthem Slàinte Mhath (a Scottish drinking toast) to Torch Song, in which a doctor solemnly intones that if the titular character doesn’t stop drinking, he “won’t reach 30”. The latter referenced Beat author Jack Kerouac’s famous quote: “The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow Roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes ‘Awww!’”

“It felt like, ‘Oh, I’ve got an alcohol problem, I take too many drugs, look at me, I’m a rock star, I’ve got problems,’” says Kelly. “It was all a bit clichéd and childish. It was over-dramatic, that whole, ‘Carry on like this, you won’t reach 30’ thing. He did carry on and he’s still with us now.”

The album’s title certainly laid bare the record’s over-arching themes, referencing both alcohol and cocaine use, as well as the fact that the band were, in Fish’s words, “Desperate to make a big album.” The problem was that the band simply weren’t getting on. One song, That Time Of The Night, found Fish’s frustrations bubbling to the surface.

“It was my resignation statement: ‘So if you ask me where do I go from here, my next destination even isn’t really that clear,’” he says. “Somebody had brought some coke down to the studio and I ended up doing a couple of lines, and then suddenly I was in a bedroom, there was no alcohol, and I couldn’t sleep. I actually wrote most of that lyric that night. I just felt really alienated.”

“It seemed to be that the thing Fish used to love doing, he started to hate,” says Rothery. “He was looking for people to blame.”

The powderkeg finally exploded towards the end of the sessions. An argument flared up which ended with Fish throwing a whiskey tumbler at the guitarist.

“I stormed out and that was it,” says Rothery, who says his relationship with the singer had been deteriorating since the time of Misplaced Childhood. “I was out of the band for 24 hours. But I wasn’t really close to Fish at that point. It’s unfortunate, because on a personal level we had an amazing chemistry together, but that friendship seemed to gradually dissolve.”

After some hastily arranged talks to clear the air, the band pulled themselves back from the brink of self-destruction, at least temporarily, but the die had been cast.

If Misplaced Childhood has ended on a note of defiant positivity, by Clutching At Straws all that had gone. It was the hunched figure with red-rimmed eyes sat glowering in the corner of every pub, trying to drink off last night’s hangover.

But it was a strangely romantic album too, one that wore its neurosis and self-pity like a badge. Occasionally, as on the chillingly prescient White Russian – inspired by the election of Austrian president Kurt Waldheim, despite rumours of Nazi involvement during World War II – it looked up from its half-empty glass and gazed outwards to the world at large, only to recoil at what it saw.

Musically, it was Marillion’s most accomplished and mature album yet. The sharp edges of their first three albums had been smoothed away, replaced by a sound that ebbed and flowed between triumph and introspection. They may still have worked by hammering together jigsaw pieces, but the likes of Warm Wet Circles and the tender Sugar Mice – inspired, as the opening lines suggest, by a day stuck in a depressing Holiday Inn in Milwaukee while the rain poured down outside – pointed towards the band’s post-Fish future.

Clutching At Straws was released in June 1987, and peaked at No.2 on the UK album charts – one place below Misplaced Childhood, which had reached the top spot. The champagne corks popped, though any celebrations were soured by the mood within the band.

“We weren’t getting on, and by the time we got to the tour it was intolerable,” says Fish. “The tour bus was not a good place to be. We all sat in different positions, nobody saying anything. The gang mentality had broken up.”

Except it hadn’t, not quite. The band was certainly fracturing, but on one side was the singer and on the other was everybody else.

“I remember avoiding Fish on tour,” says Kelly. “He was in 24/7 party mode. He’d say, ‘Come on, let’s go out.’ You’d go out, but he wouldn’t want you to leave. He’d make you feel like a terrible bastard for wanting to go to bed at 3am.”

From the outside, it looked like the band were flying. The first single from the album, Incommunicado, had reached the Top 10, while Sugar Mice and Warm Wet Circles reached the Top 40. They were playing arenas across Europe. But being a member of Marillion in 1987 through 1988 was a lonely place to be.

“I was going onstage every night and feeling like I was playing by myself,” says Kelly. “I was up on this big riser away from everybody, and Ian was on this big riser across the stage. You become separated from everything. At one point, Pete said, ‘I think I saw somebody up in the lighting truss during the show.’

The manager said, ‘Yeah, you’ve got 10 people up there, operating things.’”

“We were in a bit of a bubble,” adds Trewavas. “We couldn’t go anywhere without security. We had to check into hotels under pseudonyms. We couldn’t just go and do a soundcheck. It had to be: ‘So-and-so is going to pick you up at this time, then you’re going to drive around to the back of the building, that’s going to take about 40 minutes.’ Everything was being over-thought.”

“It was just fucking draining,” says Fish. “We were playing these concrete halls in Italy with shite sound, and I’d just had enough. You’ve got to remember, I’m going out there every night singing about how shite it is being out on the road. There was a kind of feedback loop going on. If I was singing fucking ABBA songs, it would have felt a lot better.”

Everyone involved says that the problem could have been relieved if they’d been allowed to have a break from touring – and from each other. But their management was determined to keep them on the road, to the detriment of the band itself.

“These were people who had been great friends of mine,” says Fish. “We were comrades. But we were so distant from each other. John Arnison should have said, ‘Everybody, go away for a year – Fish, go and do some acting, Steve, go and write some soundtrack music.’”

In June 1988, a year after Clutching At Straws was released, Marillion played the Radrennbahn Weissensee cycling track in East Berlin in front of 95,000 people. It should have been a triumph, but things had reached the point of no return.

“The gig was incredible,” says Ian Mosley. “But we came offstage and people were saying, ‘I didn’t really enjoy that.’ That’s when alarm bells went off: ‘If you didn’t enjoy that, then something is very wrong…’”

A month later, the band headlined Fife Aid, a poorly attended charity gig at Craigtoun Country Park in St Andrews organised by TV naturalist David Bellamy. It was, Steve Rothery recalls, “A fairly dismal day all round.” They didn’t know it at the time – though they may have sensed it – but it would be Fish’s last gig with Marillion.

“Things had started going properly wrong at the end of the Clutching At Straws tour,” says Trewavas. “After that, there was a kind of reluctance to get together and work.”

There was a last-ditch attempt to salvage things. The band began working on new material in Trewavas’ garage, before eventually decamping to Dalnaglar Castle, a stately pile in Perthshire which was miles away from civilisation.

“That was a terrible mistake,” says Kelly. “Not only were we not getting on, we didn’t really want to be together, and we had nowhere to go.”

“We went back to the same routine,” says Fish. “It was the same bits going up on the fucking blackboard: this is the Joni Mitchell section, this is the Floyd section. There we were again, in the same shit.”

A gulf had opened up between what the band wanted and what the singer wanted, and neither side were ready to compromise. “I don’t know if he thought we weren’t giving his ideas much of a try,” says Trewavas. “But then some of his lyrics weren’t quite what we wanted to work on, either.”

The music the band recorded in Dalnaglar, and during an earlier session in Nettlebed, near Reading, wouldn’t go to waste, with some of it ending up on the first two post-Fish albums Season’s End and Holidays In Eden. Similarly, the singer’s lyrics would re-appear on his own debut solo album, Vigil In A Wilderness Of Mirrors, and the title track of its follow-up, Internal Exile. But, as the bassist puts it: “Something had to give.” They wouldn’t have long to wait before it did.

Bob Ezrin had been scoped out to produce Marillion’s next album. The American, who had worked on such landmark records Lou Reed’s Berlin, Kiss’ Destroyer and Pink Floyd’s The Wall, flew to the UK to meet the band.

“Bob came down to meet the band in some studio in Surrey,” says Fish. “He said, ‘OK, play me what you’ve got.’ And the band played all the bits and pieces they had. And Bob said, ‘There are no songs here. These are just bits.’ After Bob left, the band started going, ‘Alright, let’s try joining this bit onto this bit.’ And I just went, ‘This is a waste of fucking time. I can’t deal with it.’”

The singer headed to his cousin’s house in Wiltshire. “I drunk a 40-fluid-oz bottle of Jim Beam on my fucking own, and I was still standing, because I was so stressed and tense.”

He woke up the next morning with a clear head and made a decision that would change his life and alter the course of the band. “I wrote a five-page letter, got it photocopied at a local office suppliers and paid for a taxi driver to deliver it to everybody else’s house. I basically said, ‘Either fundamental changes are made within the management and we get rid of John Arnison or I’m leaving.’ The next thing, I get a phone call from management saying, ‘The band have decided to accept your resignation.’”

“Fish said he wanted 50 per cent of all the publishing and all the writing,” says Mosley. “That’s when it got out of hand. Everybody said, ‘This has gone too far.’”

This is where memories diverge. Mark Kelly says that Fish spoke to the band’s manager a few days later, suggesting that he might have made a hasty decision, something Fish refutes. But whatever happened, the outcome was irrefutable: Fish was no longer a member of Marillion.

Speaking separately to the rest of the band today, they all use the same word to describe the emotions they went through in the aftermath of Fish’s departure: relief.

“Because things had got so difficult,” says Rothery. “Fish had never really had anything to do with the writing of the music. So we knew that our musical identity was still there. We had a lot of great ideas. Maybe, slightly naïvely, we thought it would be just a case of finding someone to replace him. As if it was ever going to be that easy.”

“Fish’s departure was, ‘OK, this is part of the process,’” says Peter Trewavas. “Don’t get me wrong – it was a big thing, and we had to fill a big hole. It took us a long time to do that.”

The split was bitter and nasty. Barbs were exchanged in the press, and there was a debilitating court case between the two sides. It would be a decade before they began speaking again, by which time by Fish was deep into his solo career and Marillion had reinvented themselves with their new singer, Steve Hogarth.

“We did go through a very public and very angry divorce,” says Fish. “Nowadays, we’re absolutely fine. We all get on pretty well. I still consider them friends. But to be blunt and honest about it, neither party has ever reached the commercial success we had in the 80s. But I don’t miss it. I’m much happier with my lot these days.”

Thirty years on, Clutching At Straws stands as a strangely fitting epitaph to Marillion’s best-known 80s line-up in all its fractious, boozy glory. The great ‘what ifs’ that surround it – what if Fish had stayed, what if they’d made another album together – are the source of many a drunken argument. But in the end it’s all hypothetical. Like Kerouac’s Roman candle, the Fish-era line-up of Marillion was always going to fizzle out. Slàinte Mhath, as they say north of the border.

This article was originally published in Prog 77.