Meat Loaf died less than a year after the loss of his artistic foil, Jim Steinman.

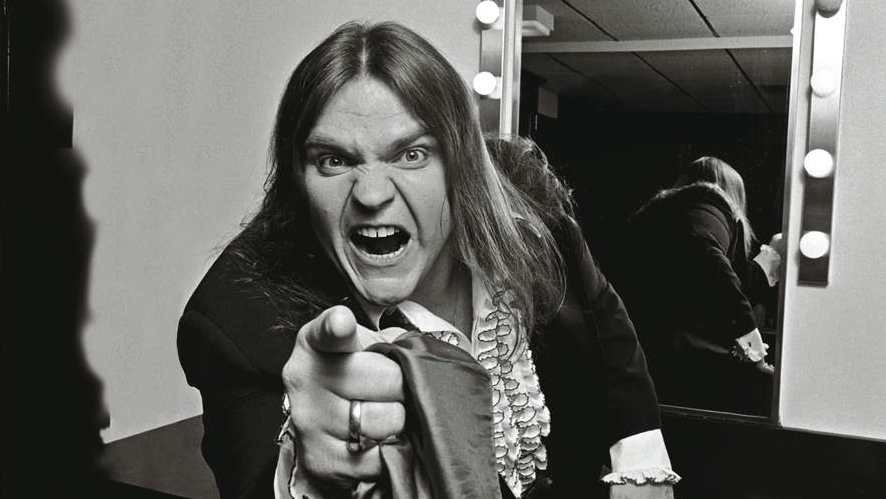

Across six decades Meat was one of music’s most larger-than-life, enduring and fascinating figures. The tempestuous synergy between the vocalist, whose talent for delivery sold the extraordinary, chart-busting album Bat Out Of Hell, and Steinman, the composer of its shamelessly excessive, uncompromisingly individual songs, was never less than riveting.

They loved one another, but hated each other too. They were brothers, but they could also be the worst of enemies. There were break-ups and reunions. Ultimately they needed one another. It just took them a while to realise and come to terms with the fact.

Before his death, Steinman had suffered long-term health issues, including two strokes. After he succumbed to aspiration pneumonia in April 2021, in an interview with Rolling Stone Meat Loaf said: “Jim and I belonged heart and soul to each other. “We didn’t know each other. We were each other.”

Meat Loaf was born Marvin Lee Aday in Dallas, Texas on September 27, 1947. His father and mother were a former police officer-turned-salesman and a school teacher. As a new-born baby his dad claimed that he resembled “nine pounds of ground chuck” and told nurses to write ‘meat loaf’ on his crib. The joke stuck, and after gaining weight as a child, reaching more than 17 stones in seventh grade, his classmates kept it going.

“Even as a kid I was so big my mother started me in first grade rather than kindergarten,” Meat Loaf wrote in his autobiography To Hell And Back, “and I was still bigger than anyone in the class.”

He was “mortified” by his original Christian name, and had it changed legally to Michael, but nobody called him that. Anyone in their right mind avoided calling him Marvin, too. According to legend, later on, during the Bat Out Of Hell tour, he actually had ‘Meat Loaf’ on his passport.

Meat’s childhood was volatile, his alcoholic father often disappearing for days. After his mother died and his dad tried to kill him with a knife, in 1968 Meat moved to Los Angeles, and formed his first band, Meat Loaf Soul. Despite constant line-up changes and an array of alternative monikers, in an incarnation known as Floating Circus he opened for The Who, MC5, the Grateful Dead and the Stooges.

He joined the cast of the musical Hair, then teamed up with Nebraska-born soul singer Shaun Murphy, known as ‘Stoney’, in an act called Stoney & Meatloaf (his name spelled as one word). Their self-titled album was released in 1971.

“Meat always sang very dramatically, scarf in hand, and I admired his flamboyant style and amazing voice,” Murphy tells Classic Rock now. Off stage, however, Meat was more of a closed book. “He was a great guy, but forever into his own thing,” she relates. “I couldn’t tell what he was thinking, even when I rented in a room in his house for a year in 1972.”

Stoney & Meatloaf was a moderate hit, and has aged surprisingly well. Indeed, Classic Rock once ranked it as the sixth-best album of Meat’s career, which, considering the size of his catalogue, is not too shabby.

After the pair parted ways, Murphy became a backing singer for Eric Clapton and Bob Seger, and continued to follow Meat’s meteoric career trajectory with admiration.

“I was extremely happy for him,” she states. “Meat finally had the course he wanted: dramatic songs and stage shows, which is exactly what he always ascribed to – big and bold!”

It was at the casting auditions for a New York production of the musical Hair, in November 1971, that Meat met Jim Steinman. Although their paths diverged when Meat, sorely lacking in funds, joined The Rocky Horror Picture Show, the early, tentative seeds of what would become Bat Out Of Hell were sown. By 1975 they were both touring as part of the National Lampoon Road Show while the plot and its songs began to take shape.

Little did either man know it, but the path to the creation of Bat Out Of Hell would be like climbing Everest blindfolded. At first nobody bought in to their vision. Those they approached within the industry called them insane.

Eventually an ally arrived in Todd Rundgren, its eventual producer, who, upon hearing the songs for Bat Out Of Hell, is said to have rolled on the floor laughing. In Meat’s book, Rundgren is quoted as saying: “I’ve got to do this album. It’s so out there.” Nevertheless, when Meat, Jim and vocalist Ellen Foley visited Arista Records head Clive Davis, he incited Meat’s rage by informing Steinman that he just couldn’t write songs.

Following their rejection, lost in fury, Meat stood on the pavement down below shaking his fist up at Davis’s tower-block office, screaming: “Fuck you, Clive! Fuck you!”

“We auditioned for so many record labels or producers that were left flummoxed and confused,” Foley remembers. “They were terrified by what they heard, the poor things.”

Meat and Jim lied to Rundgren, telling him that RCA had signed the project, and in 1976 recording began with an elite cast of musicians that included Roy Bittan and Max Weinberg, the pianist and the drummer from Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band, and Rundgren brought in his Utopia bandmate Kasim Sulton to play bass. Sulton admits that, like so many others, he was at first bewildered by Bat Out Of Hell.

“My first experience of it was when Meat, Jim, Ellen Foley and Rory Dodd [backing vocalist performed the entire record live for an audience of myself, Todd, Roy Bittan and Max Weinberg,” Sulton tells Classic Rock. “I didn’t know what to make of it; I just couldn’t place it anywhere. It wasn’t heavy rock, it wasn’t pop or metal. It was a conglomeration of lots of things, many genres thrown together to make something unique.”

Having effectively financed the album’s recording, reportedly at a cost of $235,000 (an estimate from Meat Loaf), Rundgren also contributed the ‘revving motorcycle’ guitar solo on its epic title track. Kasim Sulton believes that while the album’s vision undeniably came from Steinman and that Meat made it work, Rundgren deserves more credit than he receives. “Jim provided the laboratory, but Todd was the one who mixed the chemicals,” he says with a laugh.

Rundgren also asked his friend Edgar Winter to add saxophone breaks to three of its key selections, including All Revved Up With No Place To Go.

“I didn’t know who Meat Loaf was,” Winter admits. “I just heard this guy singing his heart out on these big, theatrical songs and thought: ‘Man, this will be fun.’ I never imagined Bat Out Of Hell would go on to be such a huge album.”

In common with Winter, Sulton promptly “forgot about” his role in the creation of Bat Out Of Hell. “A year and a half later I was driving in my car when the radio played a song that sounded vaguely familiar,” he recalls. “When I put two and two together, I thought how lovely it was that it [Bat Out Of Hell] had actually worked.”

In the studio, right from the start, sparks flew between Meat and Steinman. At one point, during the fine-tuning of For Crying Out Loud, Jim stopped the music to explain how Andre DeShields had interpreted the demo and Meat went crazy, roaring: “Don’t you ever mention another singer’s name while I’m singing. I don’t give a shit.”

In 1976, with Bat Out Of Hell still a work in progress, Meat helped out Ted Nugent, who sought a lead singer, and appeared on five songs on Nugent’s second album, Free-For-All.

“I had first performed with Meat Loaf in 1967 when Stoney And Meatloaf opened for the Amboy Dukes around Michigan and the Midwest,” Nugent tells Classic Rock. “I knew his incredible voice would be perfect to deliver my new songs, so I called him. He thundered in and did an amazing job. His work ethic, dedication to ultimate excellence and wonderful sense of humour was thoroughly appreciated and enjoyed by my whole team.”

Finally the album was completed, and, despite most of the label’s staff hating it, Cleveland International Records agreed to release Bat Out Of Hell in October 1977. Meat and company assembled a backing band called the Neverland Express that included guitar-playing brothers, Bob and Bruce Kulick.

“Bob and I auditioned and were hired to join a nine-piece band, including Meat Loaf,” Bruce recalls. “Meat had a nickname of ‘Killer’ for Bob [who died in 2020], and I was ‘Pretty Boy’. Right away it became obvious that Steinman, although eccentric, was a genius. And then of course there was this three-hundred-pound hulk of a singer who wore a tuxedo on stage. But the tour didn’t start well.”

That’s something of an understatement. The first show, in Chicago, opening for local heroes Cheap Trick was memorable for all the wrong reasons. Meat and company took to the stage in complete silence, then endured a barrage of insults over the singer’s size.

“By the end they didn’t exactly like it, but [they had stopped calling me] a fat fuck. I considered that a victory,” Meat recalled, later admitting: “It took me years to get over that show.”

With Ellen Foley unavailable due to a run on Broadway, Karla DeVito had become Meat’s on-stage partner. DeVito recalls a sobbing Meat Loaf falling into the consoling arms of tour manager Sam Ellis upon completion of the Chicago gig.

“For Meat that hostility was completely shocking because, coming from the world of theatre he was used to being adored,” she proposes. She stifles a laugh while stressing that she and Meat “never dated” throughout the four years of their first association, although the sexual chemistry between them each night on Paradise By The Dashboard Light certainly became a talking point of the tour.

Bruce Kulick believes that light bulbs went on inside CBS Records (the parent company of Cleveland) following an inspirational appearance at their annual conference in New Orleans.

“After that, CBS ensured that Meat was heard on the radio, though of course that didn’t guarantee anything,” Kulick says.

Indeed, for Bat Out Of Hell to gain traction the Neverland Express had to really put in the miles.

“Playing live with Meat Loaf was wild,” Kulick recalls fondly. “One night he ran right off the stage and injured himself. We had to do some shows with him in a wheelchair.”

Meat was asthmatic, and, given his bulk, the road crew had oxygen ready to prevent him losing consciousness.

At the age of 14, future Anthrax guitarist Scott Ian caught an early show on the Bat Out Of Hell tour, and, like so many others, was transfixed by the singer’s whirlwind torrent of hair, sweat and saliva. The show took place at the Calderone Concert Hall in Hempstead, Long Island, in May 1978.

“It was a fucking incredible experience, he was wearing the tuxedo and draped in scarves,” Ian remembers. “From that point onwards I never stopped listening to Bat Out Of Hell. It has never become old.”

Last year Karla DeVito told Classic Rock that being a part of the Bat Out Of Hell tour felt like sailing the seven seas aboard a pirate vessel, as convention was ripped up and a set of new rules written.

So who was the ship’s captain?

“That’s a great question,” she says, laughing. “I’m sure Meat thought he was the captain, and Jim was like a deposed captain who’d been placed under arrest and slung down below [in the brig]. The true captain was Sam Ellis, the road manager. Without Sam, as a live act Meat Loaf couldn’t have got past that first gig in Chicago. The pirate ship would have sunk. Sam was Meat Loaf’s confidante and truth teller.”

Sam Ellis worked for Meat Loaf from just prior to Bat Out Of Hell’s release until two years later, leaving during the maelstrom of shit that went down during the crafting of an eventual follow-up album.

“Yeah, I was the guy steering the ship,” he tells Classic Rock now. “It felt like riding the tail of a comet. We started out in the clubs with a second-hand mobile home, a station wagon and a truck, and ended up playing arenas with two tour buses and several trucks. That was challenging but it was also satisfying. From that first show with Cheap Trick we soon realised that we shouldn’t be opening for anybody. So we took it to the clubs and became headliners.”

At the time, was Meat Loaf easy to manage?

“I would say no,” Ellis responds, clearly amused by the question, “but he was manageable if you knew how. Meat had a stubborn streak, and when he became like that he would dig his heels in. There were many times when we locked horns.”

Asked for a crystalising moment when he realised that Bat Out Of Hell could achieve its goal, Ellis cites a two-show stint at the Bottom Line in New York City on November 28, 1977, which was recorded by WNEW-FM for the radio show King Biscuit Flower Hour.

“That’s when I knew that if we could hold things together, and keep on growing, what we were doing had a future,” he states.

Little did anybody realise, but the challenges were really only just beginning. When CBS demanded a swift follow-up to Bat Out Of Hell, the chasm between Meat Loaf and Steinman only widened.

The pair bickered about everything, including which take-out food to order. Making matters worse, Steinman’s precious book of lyrics was stolen. In the end, Meat lost his voice, and Jim used the material he had written for his own album, Bad For Good.

Stories from this particular period are legion. It was even reported that, seeking a cure, Meat Loaf drank his own urine. After a nervous breakdown he began taking cocaine, and there was a half-hearted suicide attempt. He also went bankrupt.

“I was out on the ledge of a building in New York and I was going to jump,” Meat relates in his book. “The police and fire department were there. Sam Ellis talked me down. I don’t even remember being on the ledge.”

Ellis believes that had Bat Out Of Hell been credited jointly to Meat and Jim, many of the issues could have been avoided.

“The record company believed Meat Loaf the more marketable of the two, but they told Jim he would get equal billing,” he explains. “Jim fancied himself as a rock star, too. But when the album came out the sleeve said: ‘Meat Loaf with songs by Jim Steinman’. That caused a lot of problems.

“Ultimately, though, while they fought like cat and dog, Meat and Jim loved one another.” Ellis adds. “They had a symbiotic relationship.”

Although Meat Loaf’s glory days as a musician were behind him, he continued to work steadily through the 1980s and beyond. Album followed album and tour followed tour. Movie followed movie. He never went away.

In 1987 he teamed up with Brian May for a rather uplifting song called A Time For Heroes that was released as a joint single. Meat had attended a Queen concert and the pair had met backstage.

“It turned out that we were mutual fans,” May tells Classic Rock. “I had followed his career all the way back to The Rocky Horror Show. I had expected this huge grizzly bear, but he was just the sweetest and most gentle guy you could meet. I don’t mean this as disrespectful in any way, but he was very childlike. It felt like he had refused to grow up in any sense. He had a strange sense of humour that you had to get used to because it wasn’t obvious whether he was serious about anything, but I really liked him. He seemed very innocent.”

Further down the line, May guested on a sequel to Bat Out Of Hell and, along with guitarist Steve Vai, on a song called Love Is Not Real (Next Time You Stab Me In The Back) on Meat Loaf’s 2010 album Hang Cool Teddy Bear. There were occasional face-to-face meetings.

“We kept in contact by email, and I got up and played with him a couple of times,” May says. “My favourite memory is when we [Queen] played an after-show party and Steve Vai and Chad [Smith] from the Red Hot Chili Peppers got up with us. Then Meat Loaf rushed to the stage, picked up the microphone and joined in. It was insane, but a lot of fun.”

Against the odds, in 1993 Meat Loaf and Jim Steinman released Bat Out Of Hell II: Back Into Hell. For anyone who doubted the potency of the reunion, the success of its first single, I’d Do Anything For Love (But I Won’t Do That) soon put paid to those doubts as it reached No.1 in 28 countries. The album has now sold more than 14 million copies.

Meat and Jim were engaged in a legal dispute for a final part of the trilogy, Bat Out Of Hell III: The Monster Is Loose, in 2006. This time hit-maker Desmond Child handled the production, and also submitted a large chunk of the material. Although seven Steinman songs were included, each was stockpiled from the past. Reviews were mixed and, compared to its illustrious predecessors, sales were weak.

But still Meat Loaf refused to give up. In 2016 he told Classic Rock: “I think of myself as a plumber. You have a leak in your kitchen, you need a plumber. You go to the book, find somebody, he comes, fits your pipe, does it quickly and well, and gives you a fair price. And if something else happens in your house, you will call that plumber back.”

Having been unavailable for the tour for the first Bat Out Of Hell due to commitments with Utopia, Kasim Sulton was on board for the one for Bat II. He became the musical director of the singer’s band for the next 17 years, and the pair developed a friendship.

“Meat could be difficult to be around and he had the capacity to create a lot of chaos,” Sulton comments candidly, “but he cared so much about the audience. Everything was about the show. I’ve played with many, many performers, and not one of them could control a crowd the way Meat Loaf did. He could take ten thousand people and hold them in the palm of his hand.”

“Away from his stage persona Meat could be vulnerable, as we saw from his character in Fight Club,” says Bruce Kulick, who went on to join Kiss and currently plays with Grand Funk Railroad. “But mostly, what you saw was what you got. His wonderful skill as an actor made him perfect for delivering the songs of Jim Steinman.”

In a strange twist, 33 years after witnessing Meat Loaf’s show, Scott Ian married the singer’s daughter, Pearl. Together they have a son called Revel.

“The first time I met him after we began seriously dating, I had no idea what to call him. ‘Mr Loaf’ just didn’t sound right,” Ian says now, laughing. “I had to ask Pearl, who said: ‘Everyone calls him Meat.’ So it was Meat.”

Ian admits to being massively intimidated: “I was extremely nervous, and I very much recognised the pecking order.” He and Meat would bond over music, films, television and sports, specifically the New York Yankees. “Meat was the perfect father-in-law, father and grandfather,” he relates with sadness.

Meat Loaf’s death elicited much emotion from all corners of the entertainment world. There was obviously a lot of love for the big, wide-eyed Texan with a voice like no one else.

“I suspect that Meat had some idea of his place in our hearts, but in this business it’s hard to gain real perspective,” muses Brian May. “Meat was a very private person, and I would imagine that his public life didn’t impinge on him twenty-four hours a day.

“It’s odd that maybe he was better known in Britain than the States,” May continues. “Meat was one of those guys that people felt they knew, even when they didn’t. The last time I saw him was when he played the O2 Arena in London, and he was struggling. He had physical problems that affected the way he sang, and everybody inside that sold-out venue poured out their love. Nobody was critical. He was absolutely adored by his British fans.

“Meat Loaf was like a fantasy figure,” May sums up. “A bit like Freddie [Mercury], people saw him and thought: ‘I could be that super-hero’. He was inspiring.”

“Meat Loaf never failed to put his heart and soul into every song, every performance, every night,” says Ted Nugent. “He was the real McCoy. The man was focused and ferocious. I loved him and will always love him for all that he was.”

Karla DeVito and Shaun Murphy both remained close with Meat Loaf till the end. “Since he moved to Nashville a few years ago we went out to dinner, talked all the time, and had started making plans for a duet on a new album he was brewing,” Murphy says. “I was helping him check out songs, writers and producers.”

As recently as September 2021, Meat spoke to DeVito about a tour. The pair even discussed how to present Paradise By The Dashboard Light differently to reflect the passing decades.

“Meat said that he would fix how he was walking, which I know was a great frustration to him [he had undergone back surgery four times], and his enthusiasm was so contagious that I could almost imagine him pulling it off,” she reveals. “At our ages nobody wanted to see us kissing during Dashboard, so he had decided that the stage would go black, with the original make- out scene being shown. So I said sure... I’d do it. I even agreed to dye my hair black again.”

On the day that Meat passed away, his daughters called Karla and held the phone to their father’s ear to allow a final conversation.

“Even now it seems impossible that he has gone,” she says, emitting a deep sigh. “With Meat and Jim passing less than a year apart, I can only consider myself truly blessed to have worked with both of those giants."