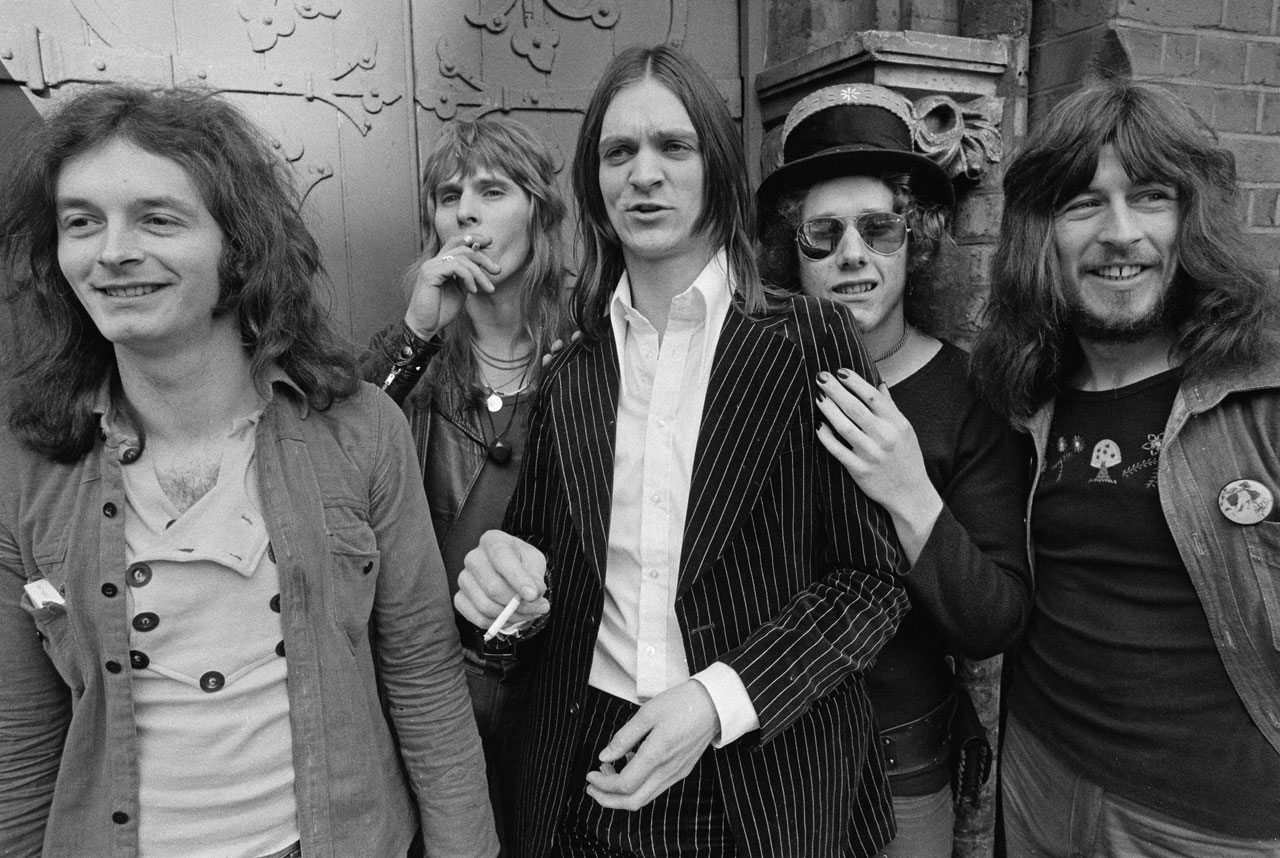

It’s October 20th 1972 and, after a year-long split, Free are back together and touring again. They’re closing their set at the richly-storied Mayfair Ballroom, the Newcastle venue which, just four years before, hosted the UK debut of Led Zeppelin. The place is packed and the band are in boisterous mood. Fuelled by all this and much more besides, Paul Kossoff slips his beloved 1959 Les Paul off his shoulders and hurls it high in the air. But he doesn’t catch it. Instead the hefty guitar – all nine pounds of it – lands headstock-first at his feet, a portion of the neck sheering off on impact. It’s a disaster. The valuable instrument is rendered useless. And there’s still the encore to go.

Enter Arthur Ramm. Today, he’s a charming, softly-spoken Sunderland man in his mid-60s. Back then he was the guitarist in Beckett – hotly-tipped and freshly signed to Warner – the support act for Free that night. Their road manager had sought him out, telling him Kossoff needed to see him urgently. “I went in the dressing room, and Paul had my guitar around his neck. He said, ‘Listen do you think I could borrow this? I need it for the encore.’ Well I was delighted! Of course you can! And so he did two encores songs, with my guitar.”

For most guitarists, having Paul Kossoff play your instrument live would be a blessing, but for Ramm the story didn’t end there. Kossoff was really taken with his guitar – a ’68 Les Paul Goldtop that Ramm had stripped and given a custom sunburst finish. Kossoff offered him another, more battered guitar – the Les Paul he’d played at the Isle Of Wight Festival in 1970 – and money on top. Ramm agreed, but only on the proviso that, when it was repaired, it was the then-broken but superior ’59 model that would be his.

Soon after though, Kossoff went back on the deal, and wanted the Isle Of Wight guitar back. An honourable, affable fella, Ramm consented, and went down to Kossoff’s house at 5 Goldbourne Mews in London to return. “I think if I hadn’t swapped it back I wouldn’t have met him again. But I did meet him a few times. We were acquaintances rather than friends, and we never jammed, but I wish we could have done that.”

Fatefully, that Mayfair Ballroom gig would be Free’s last. Their reunion had been in part an attempt to help lift Kossoff out of his spiralling drug addictions, but his illness blighted the shows, leading to ropey performances and cancellations. Just the month before at the same venue, he reportedly had a seizure during soundcheck.

“Whenever I spoke to him he was slightly drunk, or under the influence,” says Ramm. “He seemed quite nice, and everybody wanted to cuddle him because he had a baby face and he was small, probably only about five foot three. But he played great guitar. He’s a national hero up here [in the North East], and deservedly so. His life ended too quickly.”

Kossoff died in 1976, but even four years later the memory of that broken Les Paul hadn’t faded for Ramm. By then it had been repaired by another 70s cult figure, London guitar guru Sam Lee, who had – miraculously – salvaged most of the neck and refurbished the rest beyond all expectation. By this point Beckett had split, and vocalist Terry Slesser had joined Kossoff’s post-Free band, Back Street Crawler. He put Ramm in touch with Kossoff’s girlfriend, Sandie Chard.

“Sandie said she knew Paul had promised me the guitar and had welshed on the deal,” says Ramm, “and she’d talk to his dad, the actor David Kossoff. I thought it would go to a Clapton, Page, Green or Beck, one of these wonderful, monster players. But a few months later she gave me David’s number, I spoke to him, and he said if I wanted to buy it, I could.”

And that Les Paul has been in Arthur Ramm’s hands since ’76. He left Beckett, having been replaced in time for their sole, self-titled album for Warner, but he kept playing, with the highly successful Les Humphries Singers in Germany, and more recently in Just Us Four and Snake Eyes, rock bands working the pubs and clubs across the north east. The Kossoff Les Paul was his gigging guitar, right up until the end of the 80s.

“I wasn’t bothered about its value, it’s just a great musical instrument. But then around 1989 I noticed Paul’s name started coming back into vogue, he started getting more popular again. People at gigs kept asking me all these strange questions: Is that the Kossoff guitar? It must be worth a lot? How do you store it? I started thinking I’d better not play it any more, in case someone decides to take it home with them!”

Someone who did get their hands on it since was Joe Bonamassa. He’d heard about the guitar and invited Ramm to his Newcastle City Hall show in 2010, and played some Free songs on it in tribute.

Arthur Ramm is in his middle 60s now, and thinks it’s time to let the guitar go. “I know it’s worth a little bit of money and that’ll help me in my later years. But it’s not only about that. It’s time for somebody else to have it and enjoy it. It’d be great for it to go to a musician, someone who’ll take care of it.”

But what’s the best way of ensuring a sale like this is handled correctly? Having made enquiries, Ramm was advised to go to the auction house Bonhams, due to their expertise in selling musical memorabilia. After all, they have been in the game since 1793.

In the year Kossoff died, Stephen Maycock was a wannabe musician himself. On Wikipedia he’s even cited as the first drummer for London punk band, The Members, but he plays that down, as we speak to him at Bonhams’ offices in London. Today he is the Consultant Specialist for their Entertainment Department, offering his expertise on film and music memorabilia. No two days are the same for him. The day before we speak to him about this guitar, Bonhams had a sale of personal effects and props belonging to the late director/actor Sir Richard Attenborough. A replica of the amber-handled cane he used as John Hammond in Jurassic Park fetched £13,000. (£13k, for a replica.) In the past Bonhams has handled the sale of items linked to a host of artists, Angus Young, Bruce Springsteen, Pete Townsend and Roger Waters among them. In 2007 one of Jerry Garcia’s favoured Travis Bean guitars went at Bonhams’ US branch for a whopping $300,000. In 1990 Maycock sold Hendrix’s white Woodstock Stratocaster for $325,000. Given these amounts of money, you need an expert like Maycock to ensure all is as it should be.

“When you look at something like a guitar,” Maycock says, “the very first thing you ask is, who played it? Where is their position in the list of all-time great rock guitarists? In this case Paul Kossoff is in the top league, and that’s the bottom line. Also, has it been used on any notable recordings or concerts. That’s difficult to ascertain here. Paul owned a number of Les Pauls in his life, so while he bought and sold guitars as needed we know he kept hold of this one, from ’70 to his death in ’76, the vast majority of his playing career. So it’s fair to say he would’ve played it a lot. He kept it because he really liked it.

“We also consider if the guitar is inherently a valuable instrument, even if it were just played by Joe Bloggs. In the case of a 1959 Gibson Les Paul Standard, it does have inherent value. It’s been bashed up, the neck was broken, it’s got lots of knocks and scratches and the sunburst has faded, so it’s far from a pristine example of that model. But all of that doesn’t matter because of who played it. Paul is generally acknowledged as one of rock’s great guitar players.”

Provenance is also vital in the auction game – you must be sure the item is what it’s claimed to be. Sellers usually have to provide evidence of the chain of ownership between themselves and the famous source. “Then there’s visual evidence,” says Maycock. “Does the item have any particular features or marks that were there originally that you could match up to photographs or film. If all that fits and you don’t have any gaps you can be reasonably sure of the provenance. With this one, Paul Kossoff owned it, then Arthur owned it. It’s all there and has been well-known for some time, so that’s fantastic. It’s one step from getting if from Kossoff himself.”

Based on all this, Maycock is expecting this guitar to achieve a six-figure sum. “It’s not the average collector’s thing, because most of them don’t have that sort of money, but we think six figures is a reasonable number. Eric Clapton sold some of his most famous guitars lately, but items like this one don’t come up very often.”

While Kossoff’s guitar might come close, for an auctioneer in this field certain instruments represent the holy grail – dream items that will probably never enter their catalogue. “Paul McCartney’s Hofner bass guitar has to be one of them, but that will never be for sale. Brian May’s Red Special, again, is one of a kind, but will surely never be put up for auction. A lot of the holy grail items have already been sold – Hendrix’s Woodstock guitar for instance. That’s in a museum in Seattle now. The Sgt Pepper drumskin’s been sold twice.”

Paul/Arthur’s guitar will be just one of the lots at Bonhams’ Entertainment Memorabilia auction, taking place at its Knightsbridge saleroom on December 10th. Among the other items going under the hammer that day include a Lindner upright piano on which ABBA composed some of their biggest 70s hits, Bob Marley’s handwritten lyrics for Keep On Movin’, and, an Eric Clapton Signature model Strat used on tour by one of the UK’s biggest pop stars, Ed Sheeran. While potential bidders must register, the auction is free to attend. “After all the pre-sale build-up,” says Maycock, “you don’t have a clue whats going to happen, until the auctioneer opens the bidding. You don’t even know if its going to sell. Until the hammer comes down its fairly nail-biting stuff.”

It’ll be a big day for Arthur Ramm, for sure. But he’s in two minds about whether to be there. “I might go, but I might just stay up here [in Sunderland]. It’s too much for me to think about at the moment. I’ll be sorry to see the guitar go, but there’ll be a bit of relief too.” And then, fondly, this: “I’ve been very fortunate to have it for company. Bonhams picked it up in September, and the day before I had a gig with the band, so I took it out and gave it one last play.

“It’s out of my hands now. We’ll see what happens.”