The groundbreaking releases that weren’t necessarily full albums.

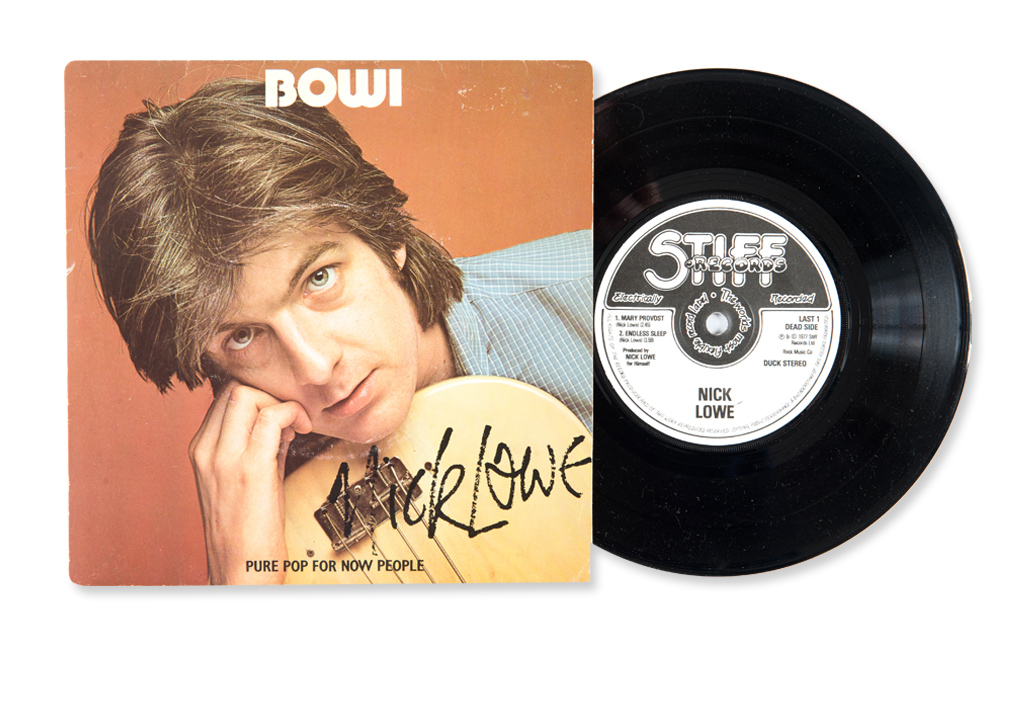

NICK LOWE

Bowi (STIFF, 1977)

Stiff Records’ inaugural EP summed up the sense of puckishness at the heart of Britain’s first great indie label. A playful commentary on David Bowie’s Low, which had been issued some months earlier, Nick Lowe levelled the field by dropping the ‘e’ in response./o:p

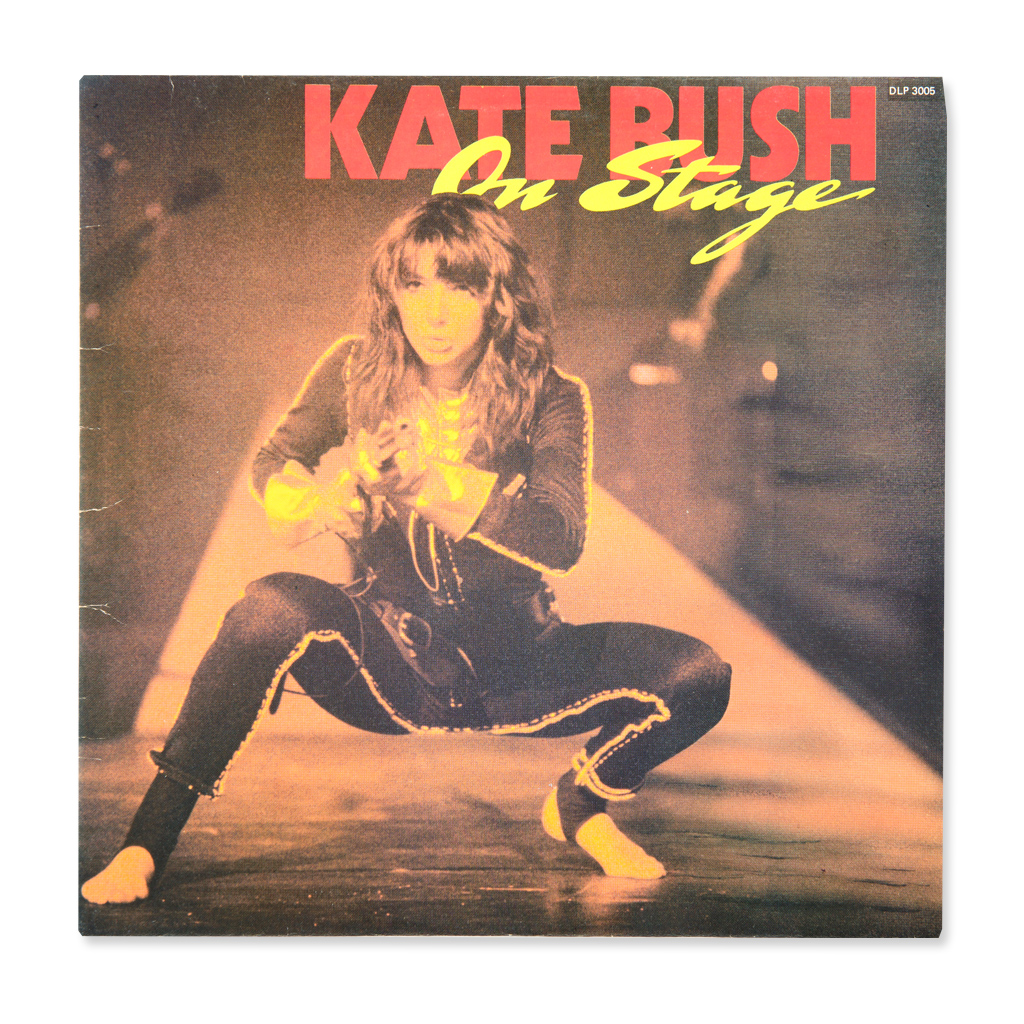

KATE BUSH

On Stage (EMI, 1979)

Nobody does ‘tantalising’ better than Kate Bush, and these four tracks, which were recorded live at the Hammersmith Odeon on her Tour Of Life in 1979, provided a fascinating yet frustrating snapshot of her mesmerising stage show. The version of James And The Cold Gun included here is quite superb./o:p

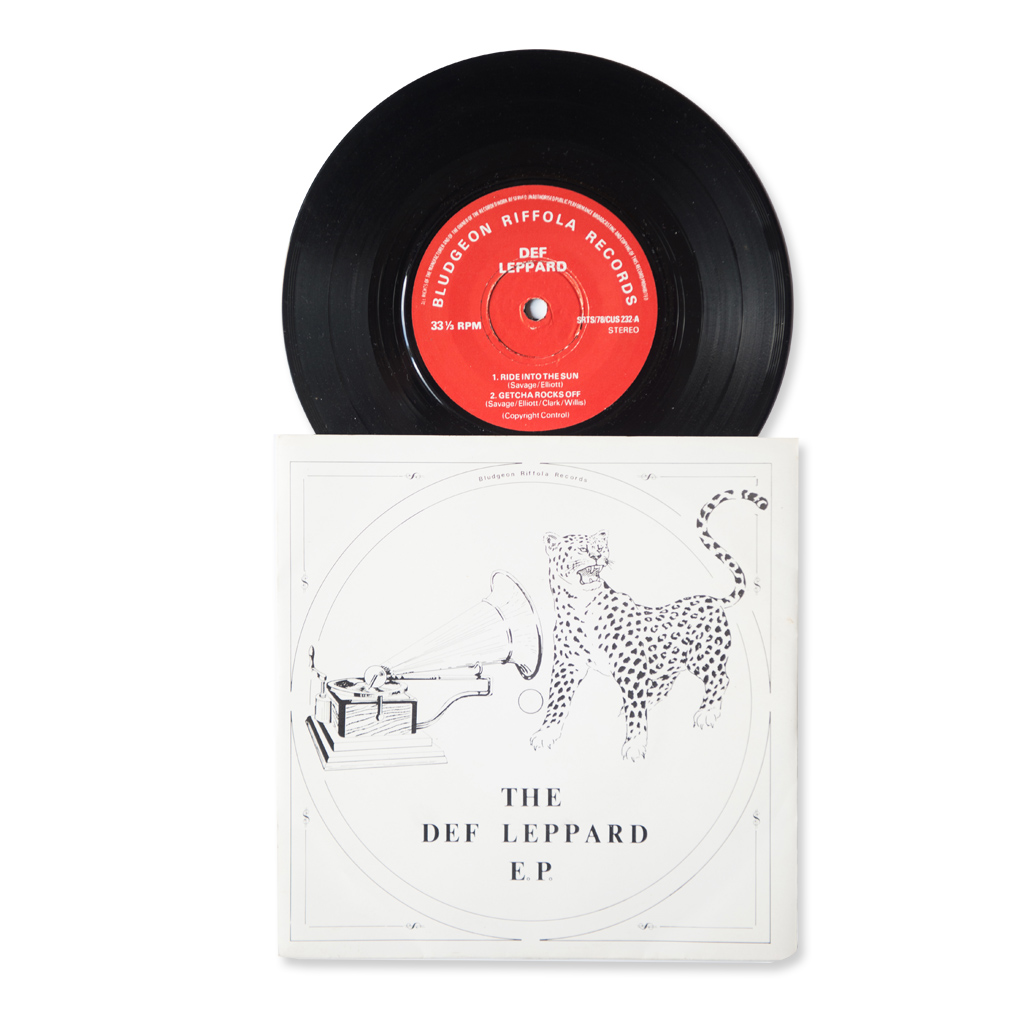

DEF LEPPARD

The Def Leppard EP (BLUDGEON RIFFOLA, 1979)

Funded by a loan of £148.50 from the dad of singer Joe Elliott, the three-track Def Leppard EP provides a deliciously modest glimpse into the birth of one of the world’s biggest hard-rock sensations. Elliott even included a photocopied lyric sheet with each EP./o:p

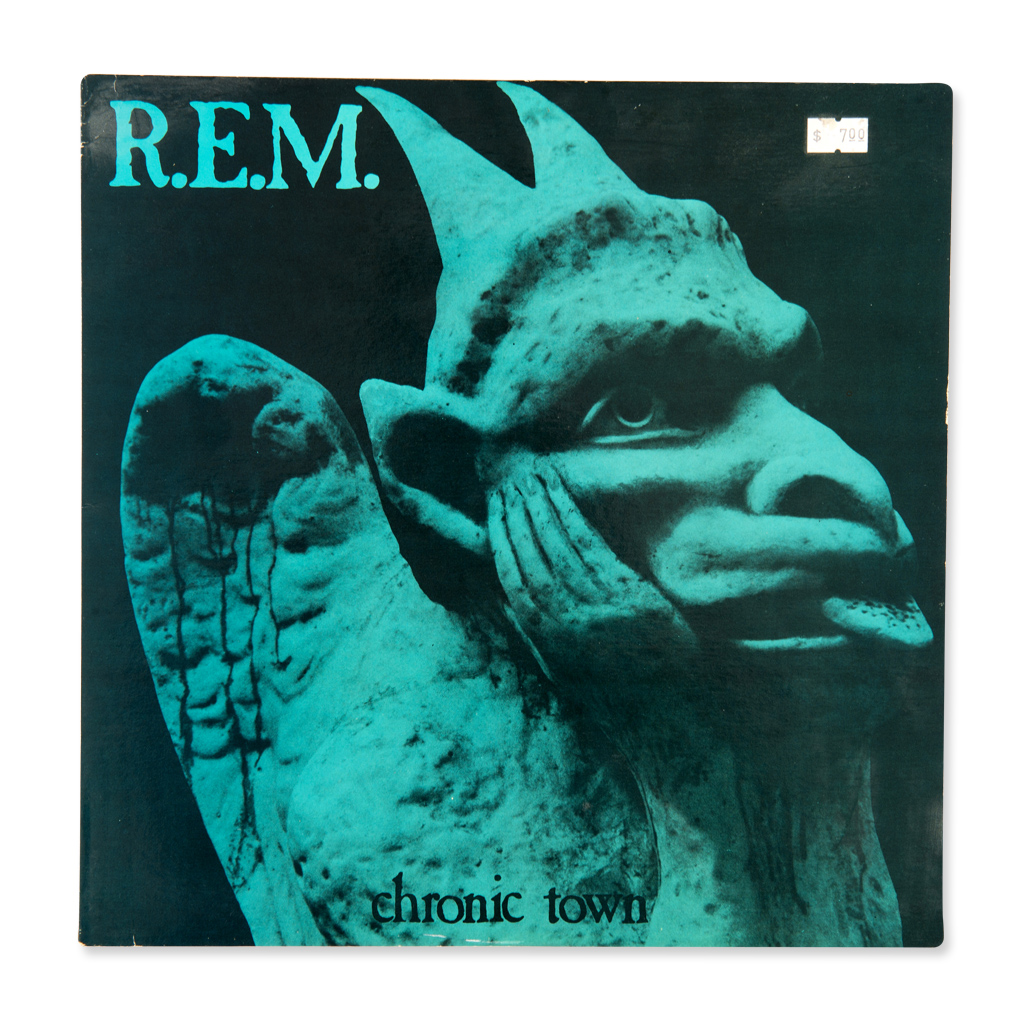

REM

Chronic Town (IRS, 1982)

REM’s first EP raised the curtain on their enigmatic brand of subterranean rock. Their sense of mystery was deepened by cryptic songs that sounded like they had been recorded in thick fog, the indecipherable lyrics and a sleeve whose glum gargoyle offered precious few clues./o:p

TWISTED SISTER

Ruff Cutts (SECRET RECORDS, 1982)

Twisted Sister allowed their music to do all the talking, playing down the visuals on a four-song 12-inch that included stage-set opener What You Don’t Know and an unforgettable, Eddie Kramer-produced stomp through the Shangri-Las track Leader Of The Pack./o:p

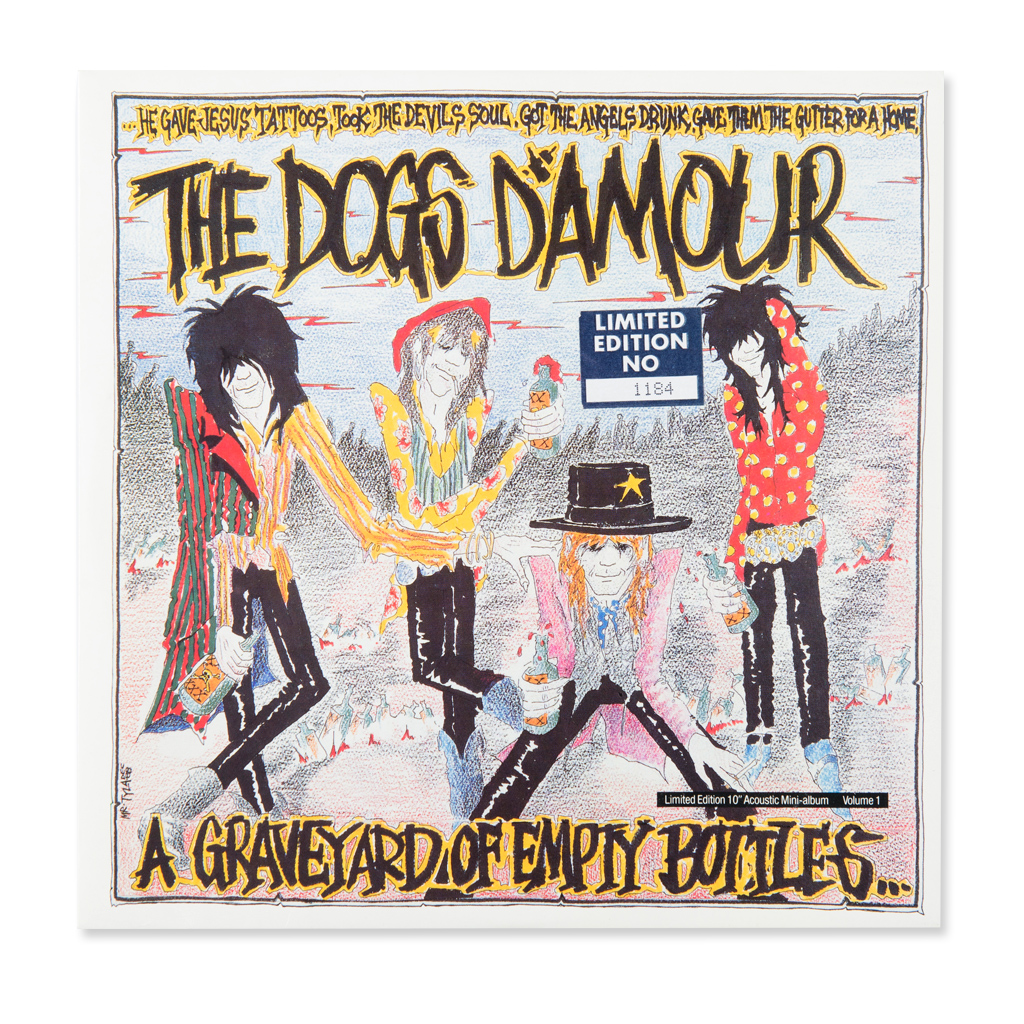

THE DOGS D’AMOUR

A Graveyard Of Empty Bottles… (CHINA, 1989)

Billed as “soft songs for hard people”, this numbered 10-inch acoustic mini-album revealed singer Tyla’s raw underbelly via eight unplugged ditties, spread across a Blue Blooded Bar Side and its Fifth Of Whisky counterpart, and all wrapped up in his ever-identifiable artwork./o:p

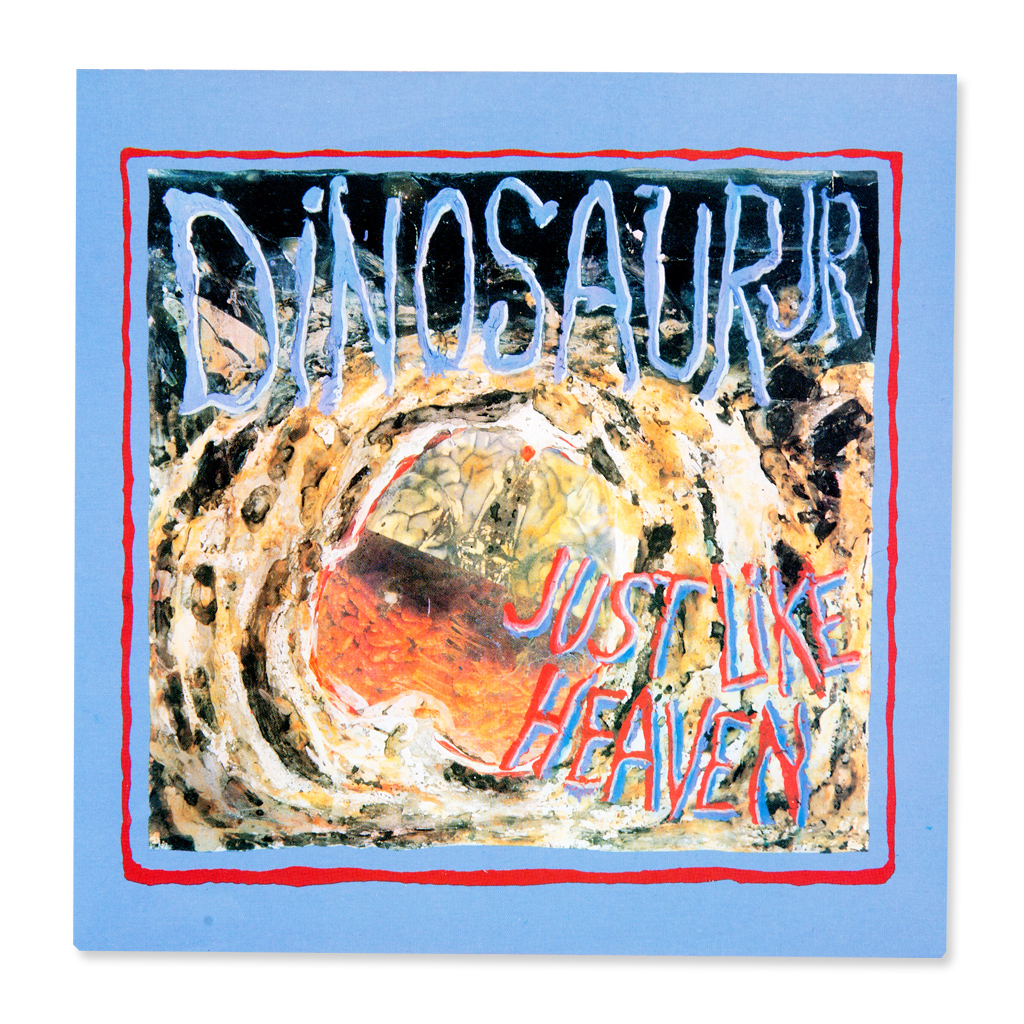

DINOSAUR JR

Just Like Heaven 12-inch (SST, 1990)

Covering The Cure’s sublime Just Like Heaven was an inspired move by J. Mascis’s ragged stoner-grunge crew, and one enhanced by the single’s 12-inch incarnation, which was released on one-sided vinyl. The non-grooved side was embossed with a psychedelic bas-relief engraving. Far out./o:p

ALICE IN CHAINS

Jar Of Flies/Sap (COLUMBIA, 1994)

Two brilliant EPs in one gatefold sleeve, and 1992’s Sap’s first appearance on vinyl. Upon first putting the needle down, everything we thought we knew about Alice In Chains dissolved. Stripped of their usual thunderous riffage and nihilistic bombast, both EPs’ bleak introspection and sparse acoustics required a new vocabulary for discussing their sound: “mature,” “melodic” and “gorgeous”./o:p

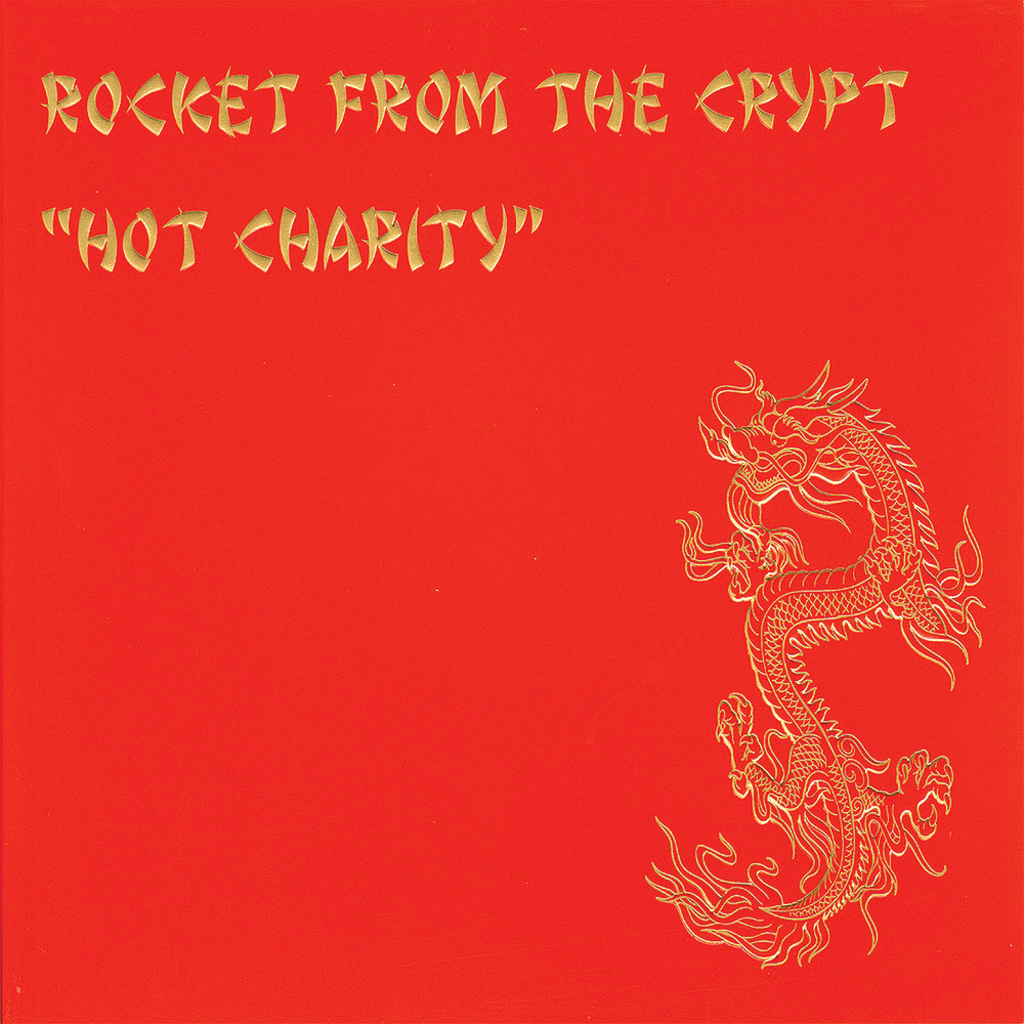

ROCKET FROM THE CRYPT

Hot Charity (ELEMENTAL, 1995)

A savage jolt of horn-pumping rock’n’soul that served as RFTC’s entry point to the UK, Hot Charity was issued on a purely fictitious imprint (Perfect Sound Records) while the band waited for Interscope to issue their major-label debut, Scream, Dracula, Scream!. A key moment in the Second Coming of garage rock./o:p

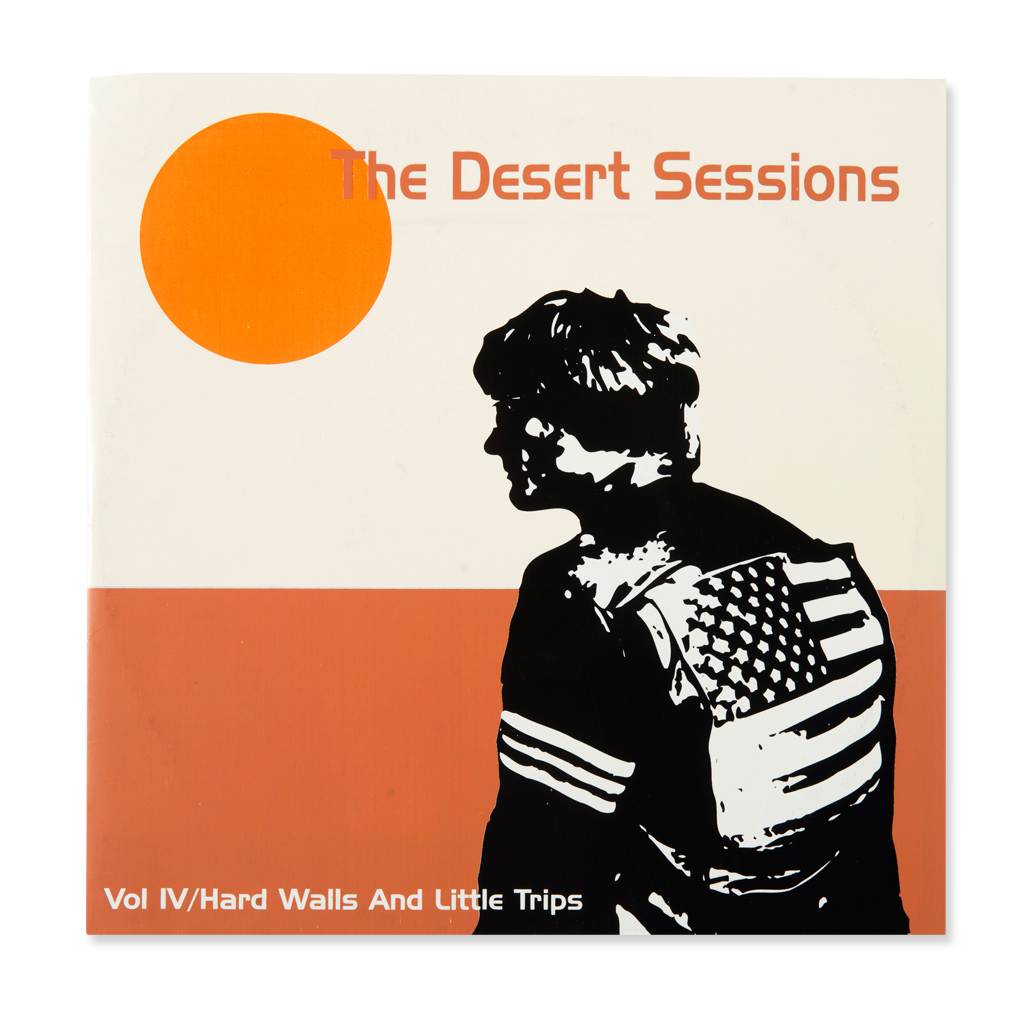

DESERT SESSIONS

Volume 4: Hard Walls And Little Trips (MAN’S RUIN, 1998)

Josh Homme convened his rotating alt.rock supergroup for 10 trippy desert blowouts. With its mesmerising grooves, the white 10-inch of Volume 4 saw the debut of Monster In The Parasol, a song that later became a cornerstone of QOTSA’s Rated R./o:p

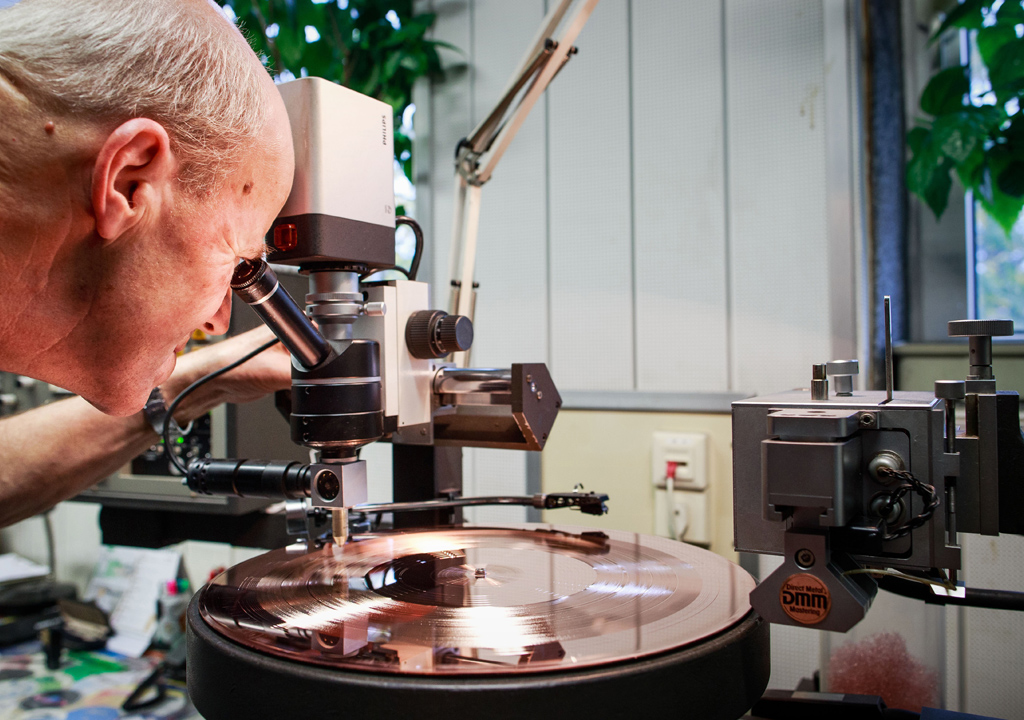

PLATTER MATTERS

From acetate to final bake: how vinyl is made./o:p

In a world where digital music seems to arrive with a simple click, vinyl manufacture resembles the intricate, time-honoured preparations at a brewery. Often veteran engineers operate decades-old factory presses, in a process that balances artisan craft, scientific precision and clanking heavy industry.

“Making records is less forgiving than making CDs, physically, mentally and financially,” says Leighton Harris of The Vinyl Factory, who took over EMI’s famous Middlesex record plant in 2001. “Every stage of a record’s manufacture is liable to contamination and problems.”

The process starts when the music from a recording studio’s master file is cut by a lathe’s stylus as grooves on an acetate, lacquer disc (or a copper one, if using LP-friendly Direct Metal Mastering). The intensity of the sound determines how deep the magnetically stimulated stylus cuts – which is one reason masters made at vinyl-appropriate lower volume work better than those designed for digital formats.

“Levels being too high can make the needle jump into the neighbouring groove,” Harris explains. “Play-time vs. volume is a constant factor, too. The higher the volume, the less room you have to fit all the groove onto the disc.”

This lacquer is then coated with silver, making it electrically conducive, ready for immersion in an electroplating bath of nickel, where an electric charge bonds the nickel to the lacquer. When removed from the bath after several hours, rinsed and oven-dried, this nickel layer is peeled away, forming a negative, “father” version of the grooved master record. The process is repeated in full with this nickel master to create a positive, “mother” version, identical to the original grooved lacquer.

A machine may then spin this disc as a technician polishes rough spurs from the grooves, before yet another round of electroplating ends with a third nickel master – the “stamper” – being peeled away. With grooves now reversed again to be a mirror image of the original, this metal disc is inserted into the press. That’s side one. This is all done for side two, too.

“Ticks and pops are usually caused by contamination during these stages of production,” Harris says. “These metalwork pieces are very fragile, and any dirt or impacts can either leave an audible fault or ruin it completely. If all else fails, we have to recut from scratch.”

Meanwhile, pellets of PVC (the actual vinyl) are melted into a hot, soft “biscuit” and inserted between the stamper sides. Labels are baked, then added from the press to the vinyl. Twenty-odd seconds and 100 tonnes of pressure from the stampers, followed by eight hours of overnight cooling, and you finally have a record.

“There are multiple problems that can happen at this final stage,” Harris warns. “If the labels weren’t baked properly they can split, and if the press wasn’t set up quite right they become off-centre. The temperature can cause the discs to warp or dish. Everything needs to be set right or it won’t make a good record.

“The whole process has stayed relatively the same since vinyl began in the 40s,” he concludes, “and uses equipment made between the 60s and early 80s. It’s unforgiving. But when it’s done right, it sounds beautiful.”/o:p