It’s hard now, to imagination or recreate the impact that The Who’s Live At Leeds had on its release on May 16, 1970.

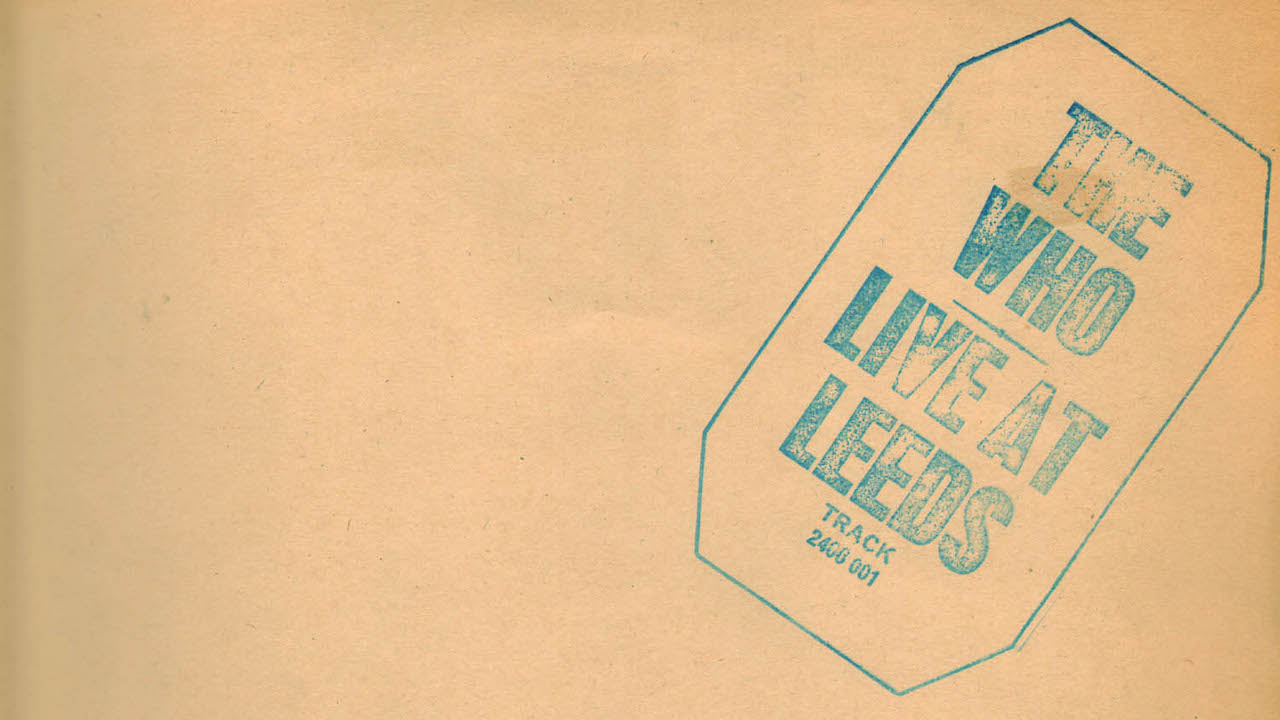

The record itself was just six tracks, three of which were covers – Johnny Kidd’s Shakin’ All Over, Eddie Cochran’s Summertime Blues and Mose Allison’s Young Man Blues – along with Substitute, My Generation and Magic Bus. It wasn’t short – My Generation was 16-minutes long and included snatches of See Me, Feel Me, Listening To You, Underture, Naked Eye and The Seeker, while Magic Bus was a blistering seven-and-a-half minutes – but it was simple, crude, brutally loud for the time and wrapped in a simple brown sleeve.

It could have seemed like a misstep from a band whose last album, Tommy, had lifted them out of the legions of 60s pop acts clogging up the top 40 and appearing on Ready, Steady, Go.

The truth is, Tommy had changed everything.

To promote the album in 1969, The Who had gone on an extended world tour and decided to record the shows for a live album. When they got back, the band’s sound man Bob Pridden waded through the tapes for three weeks and reported back that they were all good. He didn’t know where to start. With a deadline looming, it was decided that the easiest way forward was to record two shows that coming Valentine’s Day weekend – in Leeds and Hull.

After months on the road playing a rock opera, the band were at their peak and ready to let loose. Bassist John Entwistle had tired of what he saw the band becoming. In the book The Complete Chronicle Of The Who, Entwistle is quoted: “We were better known for doing Tommy than we were for all the rest of the stuff. I mean, all the guitar smashing and stuff went completely out of the window. We’d turned into snob rock. We were the kind of band that Jackie Onassis would come and see.”

Live At Leeds had no artsy concept. It came in a brown card sleeve had three cover versions and several lengthy jams. Its statement, if there was one, was about the sheer power and energy of rock music.

“I knew we had hit a roll,” Townshend told Classic Rock’s Mick Farren. “This mainly depended on Moon, of course. He was at the apex of balance between his drug use and youthful good health. Five years later he would start to slide. Moon as a musician was a great listener, and followed what John and I played. Roger feels, looking back, that Moon followed what he did vocally as well. So Moon was everywhere in these times, but playing with great affection. We also all seemed to have boundless energy.”

Roger Daltrey agrees that the band were on a decisive roll by the time the Leeds and Hull shows were recorded. “It was our playing peak, that came out of playing Tommy in its entirety on stage – or almost in its entirety,” he says. “Talk about a sixteen-round boxing match. New things were happening at just about every gig.”

Hull was expected to be the live recording, with Leeds as warm-up and back-up. And the band remembered Hull as being the better of the two shows, with the City Hall offering warmer acoustics. Roger Daltrey: “Hull was a better gig than Leeds. I remember it like it was yesterday, although in retrospect ‘Live At Hull’ doesn’t really trip off the tongue.”

Pete Townshend agreed. “It was a better performance from me – no bum notes. I was stone-cold sober, I think. At Leeds I had a drink or two.”

The problem? John Entwistle’s bass was entirely missing from the Hull recording (or so it seemed – Townshend didn’t listen to the whole thing). “I didn’t even listen to Hull all the way through,” he told Mick Farren. “The first few songs had no bass. So I didn’t even know the bass had been recorded on some songs. I just moved straight on to Leeds and mixed it. The Leeds night was covered in clicks, and most of them I literally cut out of the master tape with a razor blade. A lot of them were so bad I couldn’t fix them. It’s easier today with computers.

“I mixed Live At Leeds in my tiny home studio where I had recorded all my demos thus far, Thunderclap Newman and some stuff with the Small Faces. What distinguishes it from most other Who mixes is that the electric guitar is very loud.”

The Hull mixes were later included on a reissue (with bass from Leeds added on the missing tracks). “Even on the new Hull mixes the guitar is mixed a shade too low for my taste,” said Townshend.

The album has been remixed, reissued and expanded many times. Of the three versions available to stream on Apple Music right now, none have just the original 6 tracks. If you want to hear it as it originally sounded, you have to find an old copy or make your own playlist.

It’s worth it to hear it’s the short sharp shock that, on its release, saw it acclaimed as the greatest live album ever made. In the New York Times, Nik Cohn wrote that, “Without exception, [the songs] are shatteringly loud, crude and vicious, entirely excessive. Without exception, they're For the first time, the full force of the group has been caught on record, their un equaled ferocity and power. Somehow, whenever they've gone into the studio, they have softened up…

“With Tommy,” he wrote, Townshend had created “rock's first formal masterpiece and now, with the live album, he gets the definitive hard‐rock holocaust.”

As Mick Farren wrote in Classic Rock issue 152, Live At Leeds “reveals a band at the peak of honed chops and fluid energy. Suddenly everyone in the world wanted to see Maximum R&B for themselves, and The Who were boldly precipitated into a then very new rock’n’roll superstardom where only The Rolling Stones had gone before. The record was the band’s portal to an unreal world where audiences numbered in the tens of thousands, and Keith Moon could blow up hotel rooms and drive limousines into swimming pools.”

Farren said this to Daltrey, and the singer took exception to his description of The Who as a ‘rock’n’roll band’. “The Who were a rock band,” he said. “I used to hate it when people called us a rock’n’roll band. The Stones were a rock’n’roll band. The Who were always a rock band. Listen to Eddie Cochran’s version of Summertime Blues and our version. The tempos are completely different. Where the beat is is different.”

He laughed and echoed James Brown: “It’s on the one!”