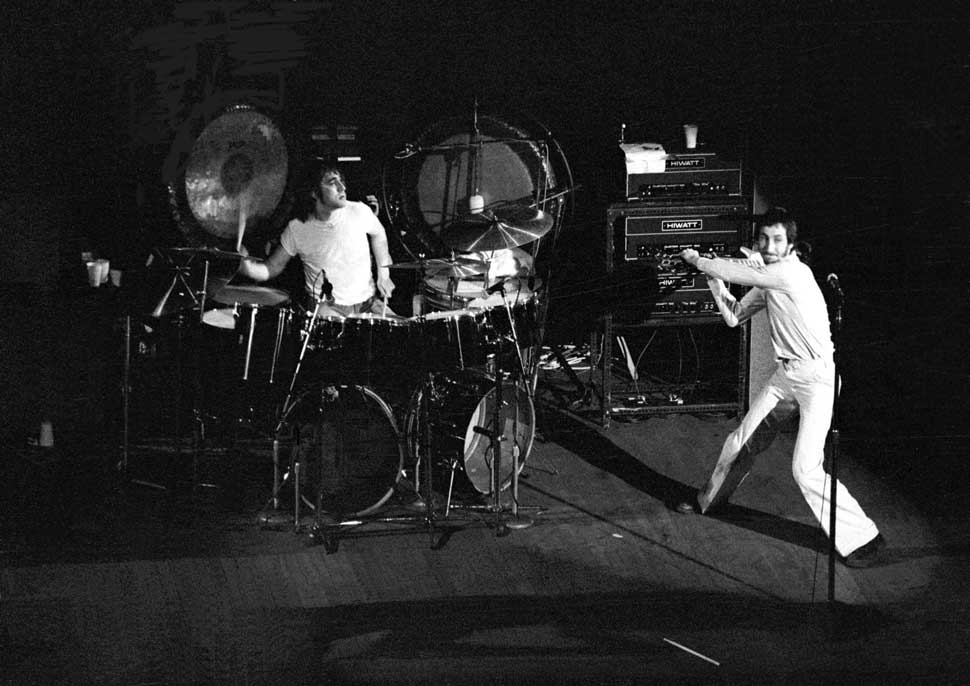

Bonfire night, 1973. The Who are 50 minutes into their set at Newcastle’s Odeon Cinema, the first gig of a three-night stand. They’re promoting Quadrophenia, the grand new opus written by Pete Townshend, but all is far from well. Audiences have been struggling to grasp the ambitious concept, leaving both Townshend and Roger Daltrey to explain the story between numbers. It’s been disrupting the flow, cramping The Who’s swashbuckling attack. And the backing tapes keep malfunctioning. As the band tear into 5:15, there’s no tape sync at all. It eventually kicks in, 15 seconds late. That does it. Townshend explodes.

He strides over to Who soundman Bob Pridden, grabs him by the neck and hauls him over the mixing desk towards the centre of the stage. Then Townshend smashes his guitar on the floor and sets about the sound board, clawing out clumps of wire and laying waste the pre-recorded tapes, before stalking off stage altogether. Much like the punters, his bandmates can only stare in silent disbelief, before the latter feel obligated to follow him into the wings. The stage curtain clunks down and an eerie quiet befalls the room. The Who are gone.

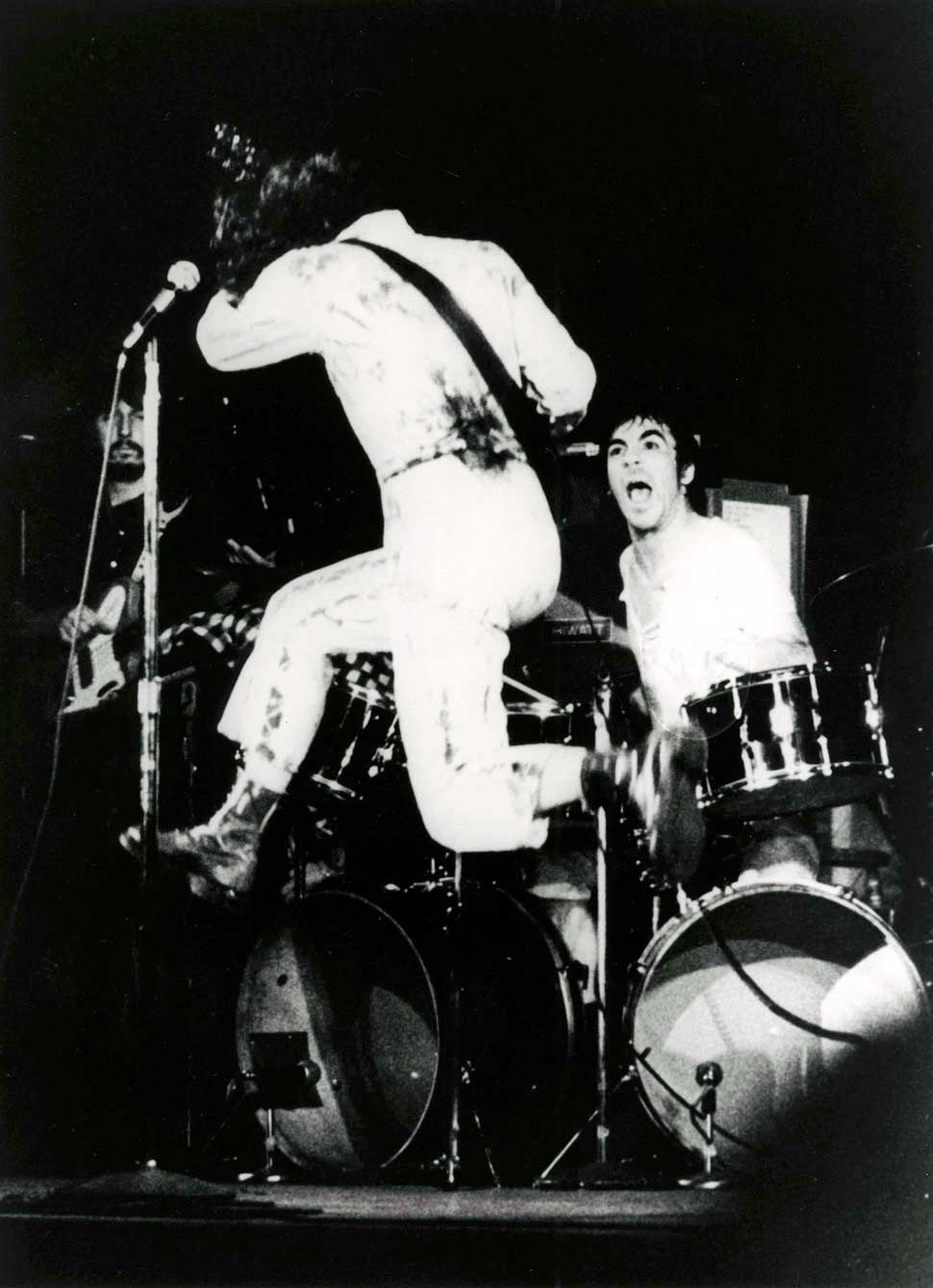

They’re back 20 minutes later, although there’s still a testy atmosphere. The Quadrophenia songs are abandoned, and the band start playing the old hits instead. Townshend clearly isn’t done. He berates the crowd for their inability to comprehend his new work, spits out a volley of four-letter words and finishes with a seismic version of My Generation, the climax of which sees him demolish another guitar – a Gibson Les Paul – and hurl an amp to the floor. Drummer Keith Moon makes similar wreckage of his kit, while Daltrey aims a boot at the microphone. Then they’re gone for good.

The audience roars its applause, but the local press scent blood. The Newcastle Evening Chronicle calls it “a ridiculous display of unwarranted violence” and “an extremely childish publicity stunt, with a potentially damaging effect on the thousands of youngsters who invariably follow their idols in all they do”.

The following day both Townshend and Moon appear on local TV show Look North to help quell the incident and confirm that the other two Newcastle gigs will still go ahead.

“Well, nobody asked for their money back, did they?” laughs Moon.

It was, in fairness, hardly unique behaviour. The Who’s formidable reputation was partly based on such wanton acts of violence against unsuspecting hardware, though the sudden assault on Pridden was altogether more extreme. This was different. Townshend’s tipping point was the result of sustained pressure and frustration.

Quadrophenia, arriving hard-at-heel after his aborted Lifehouse project, was supposed to be his defining moment of the 70s, a rock opera to out-Tommy anything that had gone before. “If Tommy is rock opera, Quadrophenia is grand rock opera,” says lifelong Townshend associate and Who biographer Richard Barnes. “If Tommy is tabloid, Quadrophenia is broadsheet. I think Pete moved The Who to another level with that record.”

But by the end of February ’74 The Who had stopped playing it entirely. “The whole thing was a disaster,” griped Townshend. It would be 22 years before they attempted it again.

Quadrophenia, likened by Townshend in 1973 to “a sort of musical Clockwork Orange”, was a deeply personal endeavour. Ostensibly about a young 60s mod at the crossroads of his adolescent life, it charts the spiritual yearning of main protagonist Jimmy Cooper through drugs, unrequited love, beachfront barneys, a string of useless jobs and unsympathetic parents.

The mod scene sours quickly, his best mate runs off with his girl, he trashes his beloved scooter and makes a break for Brighton in a desperate attempt to reconnect with the thrill and camaraderie of the mods-versus-rockers skirmishes. But the summer of ’65 is long gone. Consumed by despair, he rows out to sea to end it all, but has a sudden epiphany.

Quadrophenia the album is a record awash with metaphor – particularly the sea as both a destructive and redemptive force – and sprinkled with allusion to The Who’s own past. It is, in fact, the idealism of 60s youth culture refracted through the lens of the cynical 70s, by big, rich rock stars who’d lived through it. It’s as much about The Who as it is about Jimmy.

It’s a complex, vaultingly ambitious work that is echoed in the music itself. Surging guitars and big vocals are tempered by brass arrangements, semi-orchestral strings and intricate layers of synths and piano.

“At the time, Pete and I were writing to each other and I used to call him Tannhäuser because of Quadrophenia,” says Barnes. “Which was apt because it does sound really Wagnerian with those horns. You can imagine these big, fat ladies in helmets, riding Vespas. It’s a heavy, hard rock album but there are such delicate bits with violins and synthesisers. Pete has such a delicate touch. It’s like porcelain and reinforced concrete side by side.”

Rewind to the summer of 1972 and Townshend was in a dilemma. “I was worried about the band at the time,” he tells Classic Rock. “We were all bored with playing Tommy, and only played three songs from Who’s Next on stage. I wanted a Tommy replacement for our stage act. And the guys in the band were itchy, I think. I was definitely looking for a way to stroke the four eccentric egos of the guys in the band. We’d always been different, but by 1972 I felt I’d one last chance to do something that might hold us together and unify us in the eyes of our fans.”

The initial idea, floated by Townshend in the music press, was born out of a work called Rock Is Dead – Long Live Rock, which addressed The Who’s 60s roots. The as-yet-untitled Quadrophenia was, he said, designed to reflect the four distinct personalities within the band. But, as with Lifehouse – Townshend’s sci-fi fantasia about rock music’s ability to create a new kind of social utopia – it was less easily definable than that. He wanted to address the communal rapport between a band and its fans.

“Jimmy represented a special kind of pop-rock fan who demanded to encapsulate and reflect the members of the band he followed,” continues Townshend. “In this case the four members of The Who. So it was the reverse of what I was pitching in the music papers. In 1972/73 there were no mods, no ‘armies’ or ‘uniforms’ of any kind in the pop-rock audience, just big shirts with big collars, and haircuts from a Shakespeare play.

"Part of what I wanted to do was re-establish with our fans the principles they themselves had set up when we’d started. I think The Who had been servants of the audience in 1964/65, not the other way around. Our job was always to give our audience something they needed, not make them think we were stars.

"Inside The Who, Keith Moon was not just doing a ‘star’ thing, but taking it to extremes. He was behaving like a Saudi Prince. We all had our part to play. We’d lost perspective partly because our stage shows were so fucking intense. We felt inviolable… I think I felt a kinship with teenaged fans, but by 1972 I was 27 years old and maybe this was a last grab at writing my follow up to Tommy; my Catcher In The Rye.”

One of the central themes of Quadrophenia is the idea of joining a tribe or gang for the purposes of personal development, perhaps best expressed by the song I’m One. Townshend: “As a young man I needed, and wanted, to be part of a gang of young men. I’d grown up in a gang, one that started when I was a street kid in Acton when I was four years old, running wild when it was still safe to do so.

"What happens when you’re subsumed in a gang or collective of any kind is that you soon find the parts of you that don’t fit, that can’t be accommodated. For Jimmy – for all the piss-taking I got from the band about following the Indian spiritual master Meher Baba – what didn’t fit the mod gang he was in was his spiritual confusion, his lack of a sense of deep human purpose.”

In September ’72 Townshend had issued his first solo album, Who Came First, a devotional album dedicated to Meher Baba. Were there certain aspects of himself that couldn’t be accommodated in The Who? “It was mainly my interest in spiritual things, and artistic endeavours, that the band found hard to accommodate without taking the piss.

"Sadly, many – though not all – music critics were the same. They thought anyone who was in a band was necessarily a thick cunt who’d struck lucky, and should just shut up and play, make some money and fuck some girls, then crawl away and die and leave the analysis to them. No one in our team seemed to have any spiritual questions at all. They saw Meher Baba as a joke.”

The Who began recording Quadrophenia in early ’73. They’d recently bought an old church hall in Battersea, which they planned to strip down and convert into their own, state-of-the-70s recording studio and rehearsal room. But it still wasn’t ready, so they decamped to the mobile studio of good mate Ronnie Lane, then on the verge of leaving the Faces. Townshend singles out those early sessions as being particularly special, the band’s first major undertaking since Lifehouse and its resultant 1971 salvage operation, Who’s Next.

“With Lifehouse I really wanted a communally creative band, properly engaging with its audience, but I think it was all a bit too art school to work. Much is said about the sci-fi complexity of Lifehouse, its cumbersome narrative and the fact that I failed to explain it properly. Not so much is said about the fact that we’d become soft as a result of the success of Tommy, and then the unexpected windfall success of Who’s Next.

"The other guys in the band hadn’t had to do very much, creatively speaking, to make that happen – just support me during recording, and then do the road work to back it up. I felt really supported by the other guys, especially at the moment they first started to play my new stuff. Running through one of the first songs we recorded for Quadrophenia, I remember thinking that we’d never sounded better, or played with such conviction on unproved material. This was especially true of Roger. He sang like a raging bear. His Love Reign O’er Me will never be surpassed.”

Received wisdom has it that the rest of The Who didn’t quite get Quadrophenia to begin with, which Townshend concedes is “understandable” given that “it didn’t really land completely as a collection of songs until about three weeks prior to starting to record”. But perhaps the one member who took to the project most readily was bassist John Entwistle, who was given free rein to add some ravishing horn parts to the mix, most notably the pumping brass salvos on 5:15, the semi-orchestral flourishes on the title track and the eruptive climax to Love Reign O’er Me.

Townshend today describes Entwistle’s input as “Stunning, he was also wonderful to work with: meticulous, disciplined, funny and inspired. I loved it that he wrote out his brass parts on music manuscript paper like a proper composer. What he arranged and played on a whole variety of exotic brass instruments fit my own synthesiser and string arrangements perfectly.

"The Who members all had one great facility once we were making music: they listened. So many musicians and band members couldn’t do that. It’s the mark of a great musician, even if – like Keith Moon – he was a drummer who didn’t keep time. He listened very carefully, and what he played fit my songs perfectly.”

The initial recordings were to be produced by The Who’s co-manager, Kit Lambert, Townshend’s usual port of call for feedback on his creative works, though the dynamic of their relationship was by then in deep flux. A year earlier Daltrey had discovered what he saw as discrepancies in The Who’s bank accounts. By ’73, no doubt hastened by Lambert and fellow manager Chris Stamp’s rejection of his debut solo album, Daltrey brought in Bill Curbishley to oversee his affairs. Townshend’s more protracted shift of allegiance to Curbishley signalled the end of an era, though it was hardly a surprise to all parties.

“My strategy was always to run to Kit Lambert or Chris Stamp to fly new ideas,” Townshend explains. “By 1973 they had both lost interest in The Who to some extent. Kit had long-since left the stage as my songwriting mentor, but I was hoping he would co-produce. He turned out to be too distracted.”

Whether all this management hoo-ha informed the recording of Quadrophenia in any way is something Townshend rejects out of hand: “I don’t think the trying events around us informed the album. We were at the height of our powers as a business as well as a band. We could make studios appear out of thin air. What we didn’t have enough of was time, so the much-vaunted quadrophonic mix never happened. And neither did the quadrophonic stage act.”

Richard Barnes adds: “Who’s Next had moved them up in one way, as it was the first record not produced by Kit Lambert – it was Pete and Glyn Johns – and they’d got a new, clear sound. The other thing was that Kit started getting into hard drugs after Tommy, so he didn’t have that same influence.”

Quadrophenia featured cameos from Grease Band pianist Chris Stainton and actor John Curle (the voice of the newsreader), but otherwise it’s classic Who. First single 5:15, which soundtracks Jimmy’s barrelling train journey to Brighton, gobbling purple hearts on the way, was written while Townshend was was “killing time between appointments” in Oxford Street and Carnaby Street. “What I had was a studio track and a riff, the essential riff behind 5:15, which is a little like a Chuck Berry derivation. I stood in the street and wrote down phrases while watching people walking past. I did it again in 1976 with Street In The City for the Rough Mix album with Ronnie Lane.”

And what of Drowned and Love Reign O’er Me, two of the choicest moments The Who have ever pressed to vinyl?

“They’re two of my best songs,” Townshend agrees. “Drowned is wonderful to perform. They belong in Quadrophenia. The songs that have been most cathartic for me are probably the angrier ones. This kind of writing has always been, for me, an attempt to make the spiritual journey accessible as an idea, using watery metaphors. I explain in some detail in the [Quadrophenia reissue] liner notes how I came to write Love Reign O’er Me. It’s a kind of ‘scoop’, so I don’t want to spoil the surprise. I think Roger has dozens of fine moments, and his many live renditions of Love Reign O’er Me on recent tours have always blown me away.

“Barbra Streisand touched my cheek during the Kennedy Center Awards show [in 2008, where soul singer Bettye LaVette sang the tune] and asked me if I had ‘really written that song? It’s beautiful.’ Nice moment for me.”

The week of Quadrophenia’s release wasn’t quite as beatific though. At least one quarter of The Who seemed a little disgruntled.

“The record got delayed because there were certain problems with it,” recalls Barnes. “Roger used to complain that his voice had got lost in the mix. It was a bit of a dense, heavy mix, like an assault on the senses.”

In preparation for the album’s tour, the band were deep in rehearsals at Shepperton Studios. The simmering resentment between Daltrey and Townshend came to a head one night in late October. After a brief verbal spat, Townshend began throwing wayward punches, then pranged the singer with his guitar. Daltrey responded with a single uppercut and knocked him out cold.

“Roger punched me once,” offers Townshend today, “and I’m sure I asked for it. And he could have killed me, he had a hell of a punch. Luckily I just lost my memory for an hour or two. He was very sweet afterwards. Roger and I have had our spats, but he is really a good and loving man. I knew that then and I’m more aware of it now. But we were both under incredible strain. I’d arrived for a rehearsal four hours late, after preparing stage tapes. It’s all ancient history.”

Initial UK sales of Quadrophenia were hobbled by the vinyl shortage caused by the OPEC oil embargo, meaning that only a limited number of pressings made it into the shops before production had to be stopped. Many Who followers had to wait until the end of the tour, in November, before they could grab a copy. After which the album swiftly rose to No.2. Demand was heavy in the States, too, where it went platinum within 48 hours of release and was fended off the top spot only by Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.

Press reaction was ambiguous. Writing in Rolling Stone, Lenny Kaye praised Quadrophenia as “a beautifully performed and magnificently recorded essay of a British youth mentality in which [The Who] played no little part,” adding that “it might easily be said that The Who as a whole have never sounded better.” But he was less convinced bythe overall feel of the record, finding little evidence of telling contributions from Daltrey, Entwistle and Moon, and concluding that “on its own terms, Quadrophenia falls short of the mark”.

The NME called it a triumph, though “by no means unflawed”, noting that “some of the more extravagant production touches sound about as comfortable as marzipan icing on a half-ounce cheeseburger”. At the same time they suspected that, should the listener stick with it, “you might just find it the most rewarding musical experience of the year”.

Says Richard Barnes: “I think Pete’s at his happiest when he’s in his bunker with his tape recorder and his synthesiser, writing. That’s how I feel about Quadrophenia; it’s Pete playing with his toys. It’s like a solo Townshend project. Quadrophenia works because it’s just a wonderful piece of art, the power of the music is immense. But in many ways Quadrophenia was a failure. It was a critical success and it sold a lot, but it was one of those albums that was worthy. Everyone had it in their collection, but didn’t play it much.”

Perhaps it was the failure of the tour, with all its misfiring backing tapes and windy verbal intros. Or the reservations about the studio mix. Maybe even the relatively poor showing of its two singles – 5:15 just about dented the Top 20; Love Reign O’er Me didn’t trouble the scorers at all. Or maybe just plain weariness on Townshend’s part in the wake of such a Herculean project. Whatever the reasons, there didn’t seem a whole lotta love out there for Quadrophenia in 1973.

Fast forward to the summer of 1996. Quadrophenia has finally been remixed, with both Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend involved, and remastered on CD. The sound is sharper, clearer, the nuances of Townshend’s more intricate passages teased out in much greater relief against the bigger, more abrasively Who-like songs. Technology has finally caught up with Townshend’s original vision. It’s enough for the band to try out Quadrophenia live again.

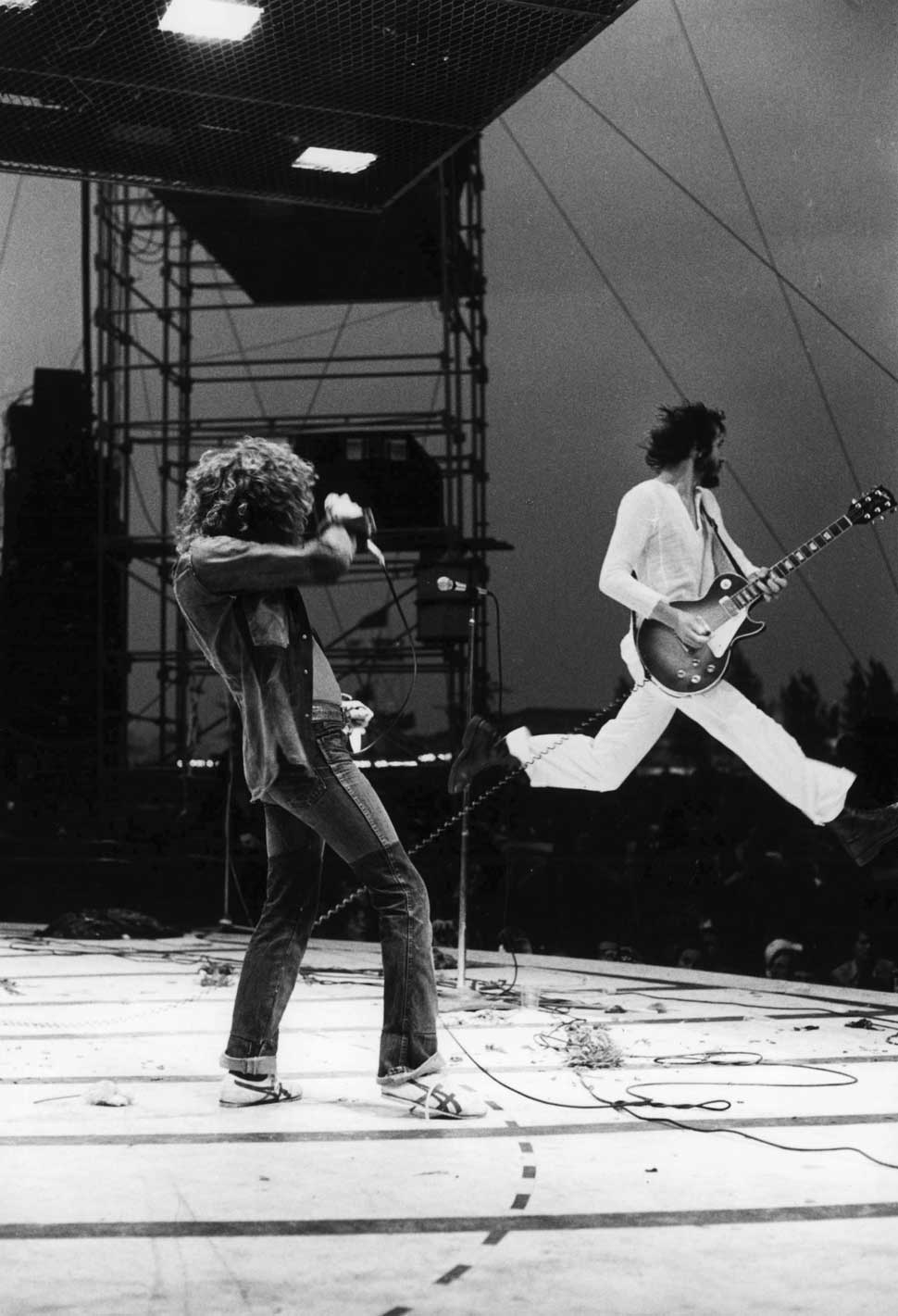

The first show is a highly theatrical, all-star hootenanny in Hyde Park, with giant video screens, and various guests taking key roles in the narrative – Phil Daniels (reprising his 1979 film role as Jimmy), David Gilmour, Ade Edmondson, Stephen Fry, Gary Glitter and, as news anchor, Trevor McDonald. It proves a huge success, enough for The Who to take Quadrophenia out on an extensive tour across the US, before returning to the UK for a handful of homecoming shows before Christmas and swinging over to Europe.

Quadrophenia is the late bloomer in The Who’s back catalogue. A record about the 60s, recorded in the proggy fug of the 70s. Even given its time-specific, niche-culture context, it feels oddly significant today. They’re songs that cut deep into the spiritual malaise; big, sweeping epics to get lost in or shake a fist to. Songs that have outrun much of The Who’s better known tunes from the era, echoing through the years with the same raw buzz as Jimmy’s bloody Vespa.

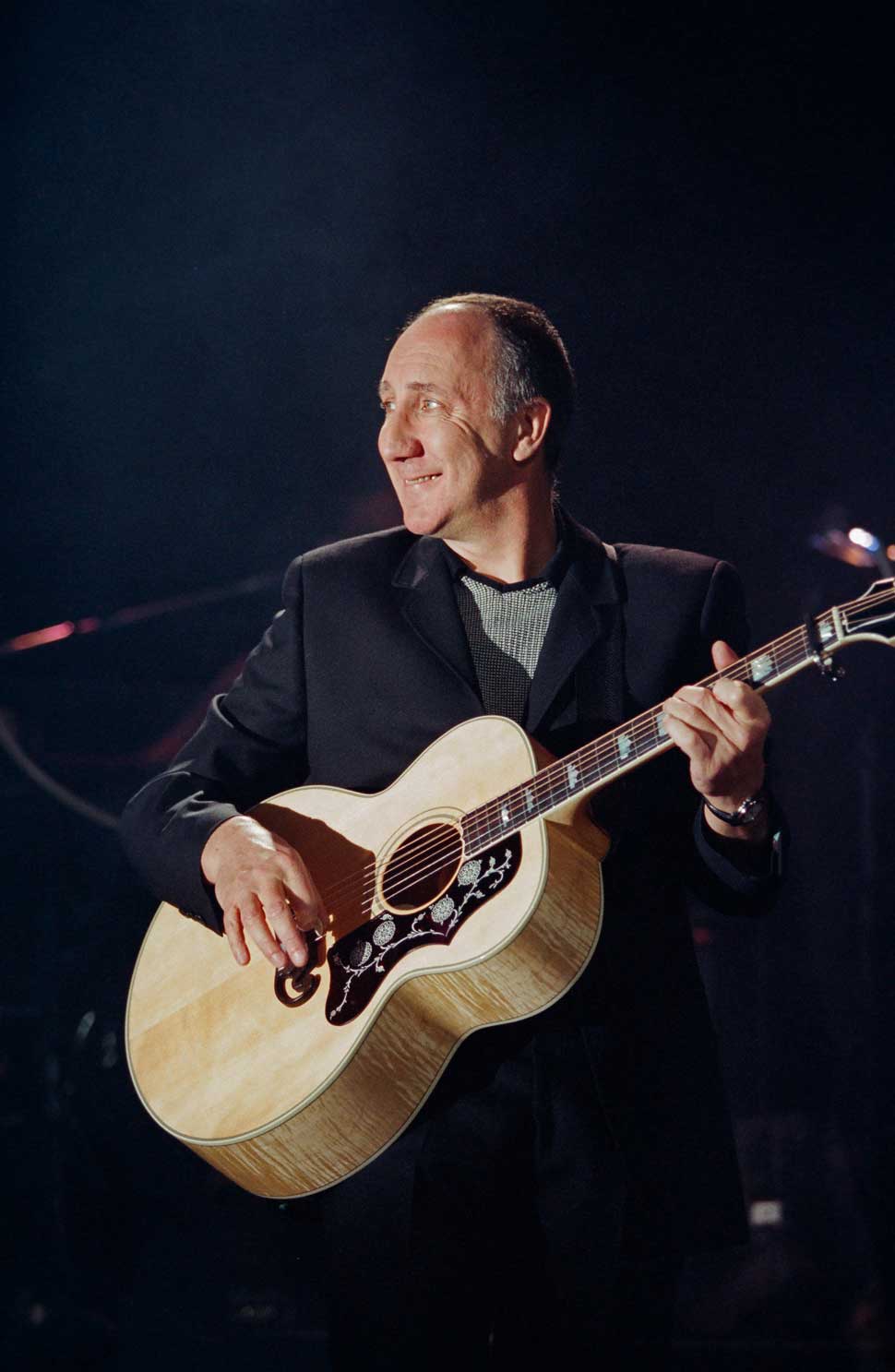

The Who even reprised Quadrophenia at the Royal Albert Hall in aid of the Teenage Cancer Trust, this time with special guests Eddie Vedder and Kasabian’s Tom Meighan. “I loved it,” says Townshend. “I suppose there was a bit of me that enjoyed it because it was such a grand celebration of the music in such a fabulous venue. Roger had total control of that show. He had demanded it when I asked him to perform it with me. I thought he did a fantastic job as a director.”

The definitive version of the album – Quadrophenia: The Director’s Cut, a five-disc box with a bushel of previously unheard demos and acres of memorabilia, overseen by Townshend – was released in 2011, and The Who toured Quadrophenia again, without resorting to violence, in 2012/13.

So how has his relationship to this boldest of bold endeavours changed over the years?

“I’ve always liked it and been proud of it,” says its creator, “but it failed to provide The Who with an alternative 70-minute rock-opera stage act to replace Tommy. I only started working on it in order to achieve that, so for a long time I was unwilling to talk about it much. It was there as an album if anyone wanted to hear it, but the big picture had never happened. In 1996 and ’97 I finally got it up in concert the way I had thought it would work in 1973. Roger was a great creative ally in making it work as an on-stage drama.

"Since then, nothing can dampen my enthusiasm for it, or my gratitude that we at least got a great album made. We had a great team.”

This original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 165, in

December 2011.