Dan Campbell is awake but exhausted, sleep-deprived yet alert.

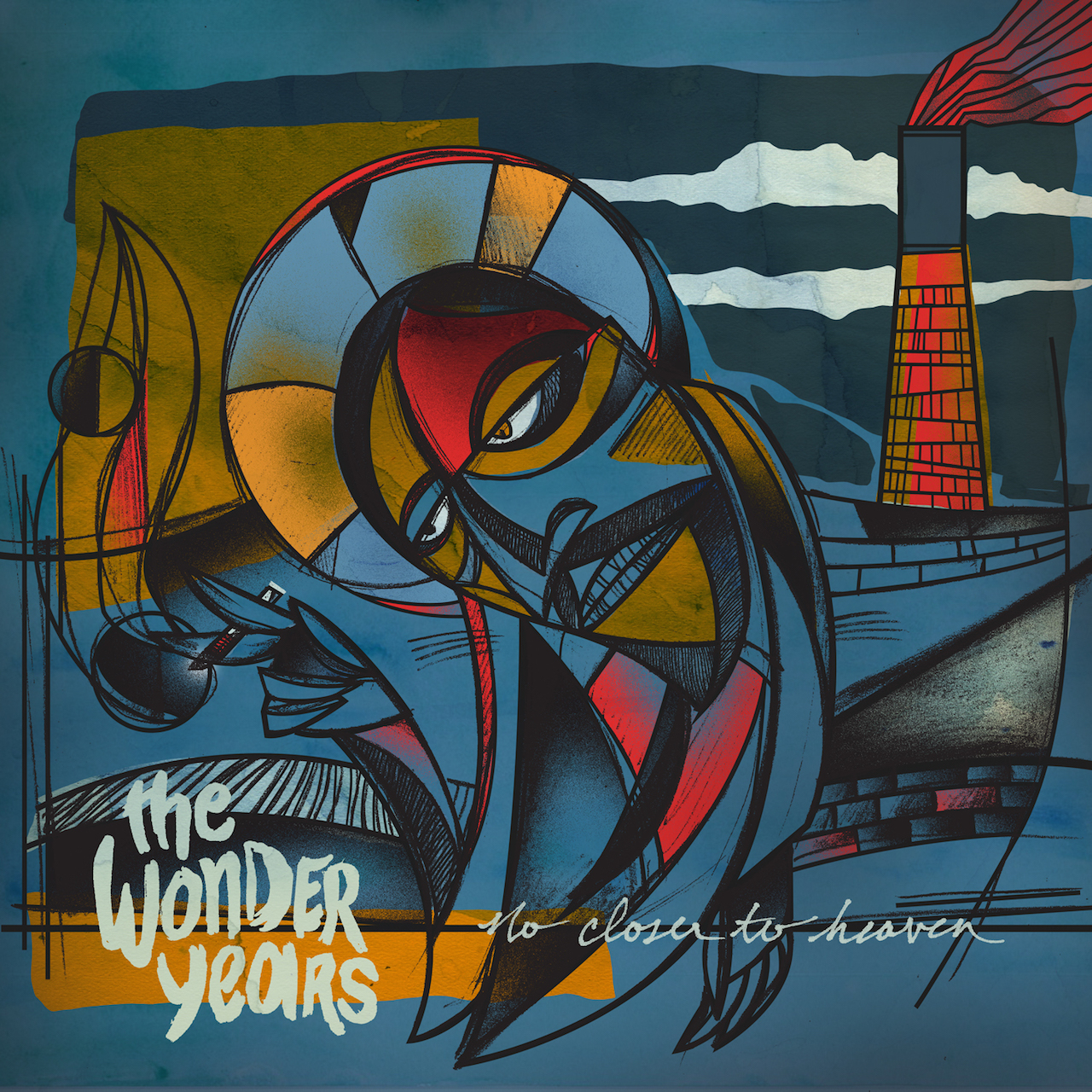

It’s the week after the singer of The Wonder Years completed a small East Coast promotional tour with his band to celebrate the release of their fifth album, No Closer To Heaven. A week later, Pope Francis will make an historic visit to the USA, which will include a stop in Philadelphia. In preparation of the religious leader’s impending arrival at the city of brotherly love, there’s been near-24 hour construction on the street outside the home of the artist more commonly known as Soupy for the past few days and he’s barely grabbed more than a few hours’ sleep in that time. What’s more, he won’t even be at home when the bullet-proofed Popemobile rolls its way through town – the newly engaged 29-year-old will be escaping town with his fiancée. No Closer To Heaven indeed.

Yet that distance and removal from the visit of Catholicism’s holiest envoy is perfectly in keeping with the theme of the record and the meaning of its title. Because while religious imagery floats like a fallen angel through the album’s 13 songs, they’re as much about absence as to what’s actually there, as much about what’s not seen as what is, and, when it comes to the loss of a dear friend, which is the album’s central narrative, as much about life as they are about death. What’s not there is just as important as what is there, and vice versa. Ironically and paradoxically, though, much of that stems from Campbell’s creative struggle when it came time to write the record, which eventually proved to be the catalyst for the album’s themes and subject matter.

“A lot of the writer’s block,” explains Campbell, “was ‘What do I write about?’ If I didn’t have that and I knew, then obviously it would be a totally different record. But it was really about, ‘Let’s not just retread the same subject matter.’ Sometimes I’d write a line and be like ‘That’s great!’ and then I would listen to it and be like ‘I pretty much said the same fucking thing last record, or two records ago – maybe this isn’t great’ and get rid of it. So that’s what helped to make it possible – I started questioning all of these lines, saying ‘Even if this is good, is it a retread?’ and I started a lot of free writing about what I wanted the record to be about. I’d just sit on my front step with my notebook for a couple of minutes and then go back in and read it and see if I could distinguish what I was trying to say. I wouldn’t start with a topic, I’d just put pen to paper and try not to stop for a couple of minutes.”

With Campbell’s self-awareness about what he was (or wasn’t) writing came the realization that The Wonder Years – completed by guitarists Matt Brasch and Casey Cavaliere, drummer Mike Kennedy, bassist Josh Martin and keyboardist/guitarist Nick Steinborn – had graduated from the Philadelphia basements and emotional insecurities and instabilities that had plagued Campbell through the arrested adolescence of the band. He didn’t know it at the time, but 2013’s The Greatest Generation ended a trilogy that had begun with 2010’s second full-length, *The Upsides *and gained almost universal critical acclaim with 2011’s Allen Ginsberg-themed Suburbia I’ve Given You All And Now I’m Nothing. It was time for something new. Even when Campbell knew that – even when the writer’s block had passed, and he had an idea of the shape the record would take and the themes it would tackle, it didn’t make things any easier.

“A lot of this record was hard to write,” he says, “because I understood that the subject matter was more important than it’s ever been. And when I started finding the things I was most upset about and thinking about the most were broader social issues – and less about myself and my own issues – that posed a new challenge. Because if I just wrote strictly about those issues it’d sound like that Ceremony song [Plutocratic Swine Rake] where they sing ‘Fuck the government with your fist’, and I thought, ‘Well, these aren’t Wonder Years songs. We’re not that band. We’re not Desaparecidos, we’re not Anti-Flag. We’re not even Hostage Calm. I was like, ‘These are the things I’m upset about, but I can’t just write these political anthems. That’s not who we are.’ And then I started to realise the reason that these are the issues I’m most upset about is because I’ve been personally affected by them. They’ve all actually affected my life and that’s why I’m more upset about them than other issues, because there are a ton of things to be upset and angry about in the world. So I thought if I connect the issues to how they personally affected me, then we’re writing Wonder Years songs – we’re writing songs about personal experiences, but those personal experiences are now in dialogue with the greater social issues that have caused them.”

The result is The Wonder Years’ most assured and confident album to date, one that extends the band’s musical progression as it expands their lyrical outlook and pushes them even further out of the pop-punk pigeonhole they were thrown into. These are still personal songs, yes, each detailed with Campbell’s trademark attention to detail and emotive and cerebral incision, but whereas previously their narratives have been occupied with internal struggles, both emotional and psychological, here, the context of a largely fucked up, politically corrupt and morally bankrupt society is impossible to ignore. Anti-Flag they may not be, but No Closer To Heaven is nonetheless a severe indictment of the world we live in. It’s an expression, too, of the depths and levels of Campbell’s thoughts when writing these songs, and, after the fact, when talking about them, which he does at length, his thoughts meandering in a state of automatic self-analysis.

“What I wanted to do,” he says, “was to try my absolute best – and I’m going to preface this by saying in some way I know that in some way I must have failed, because that is the nature of being human, that in some way I didn’t get something on this right – but I really wanted to try my really fucking best to get it right. In order to do that, that meant research and a balanced understanding of things. So let’s take Cigarettes & Saints – and we’re talking about big pharmaceutical and pharmaceutical lobbyists, prescription painkiller addiction, crooked doctors and Oxamyl, heroin, stigmatised drug culture and how we punish drug addicts and all of that….”

He pauses for a second.

“So I read. I read a lot of articles and I watched a couple of documentaries and I kind of understood – or thought that I understood – what was happening and the particular evils in it. But then I said I’m really only looking at one side of this story and that’s not fair, so I started trying to find good things that would counteract that, like look at some good things pharmaceutical companies have done, and I started calling people I knew – calling relatives that work in pharmaceutical, whether they’re pharmacists or they work for the larger companies – and I was like ‘Tell me the other side of this story, give me your portion of it so I can work with a balanced understanding of it’ and just try to get that true balance and understanding to make sure these songs were written the best that I could write them. But even once I got to the idea of what the topics were, it still was really difficult because it wasn’t just let’s write these songs about how I feel, it was let’s really think about the ideas and let’s really do some research and talk to some people and make sure, to the best of my abilities right now, make sure that I’m not writing something irresponsibly.”

Suffice to say, then, that Cigarettes & Saints is a microcosm of the myriad issues addressed by the record. Not only does it address all of the above, but it focuses directly on the character whose death – and subsequent sense of loss – is very much the centre of the record. Its opening line – “Twice a week I pass by the church that held your funeral” – also made it the song that broke through the ice of Campbell’s writer’s block.

“I had that first line,” remembers the singer, “because I never stopped driving past that church. When my fiancée was living in New York and I was still living outside of Philly, she would come see me every weekend or I’d go see her, which would been driving to the highway which would mean driving past that church at least twice every week. And so I had that line in my head and I sat down with a guitar and just all of a sudden half of a song was just out and I was like ‘Oh! I guess I was probably holding that one for too long.’ I guess that was a thing I needed to do.”

If that wasn’t enough, it examines the misguided use of God and morality within the American political system – the fact that the second debate for the Republican presidential candidates is taking place the next day results in a vitriolic diatribe about the GOP that lasts for a good few minutes – but also encapsulates Campbell’s own complex relationship with religion and God.

“America is a religious country,” he says. “Despite having notably non-religious parents – I would say at this point that my dad is a full-board atheist and my mum is kind of a non-practicing Catholic who doesn’t think about it much and doesn’t go to church. But despite all of that, I still went to Catholic school for a year and went to Catholic night school classes all through elementary school, so it was a part of the culture for me. It’s hard to shake that, because growing up you’re learning that these are the be all, end all ideas. Even though my parents weren’t specifically pushing it – their goal was for me to be well-rounded enough for me to make the decision on my own – but when you go to these religion classes, what they’re telling you is this is the concrete and unmalleable truth – that if you are good you go to Heaven and if you are bad you go to Hell and when you die you will meet your God and there is no wiggle room on any of that. This is what it is. And so you kind of have those images imprinted into your brain forever because they’re in some ways terrifying when you’re in kindergarten and they stamp your brain with ‘If you’re not good you’re going to burn in an eternal fire pit.’ It’s like ‘Holy shit! That’s terrifying!’ and that grandest idea of all that was imprinted into my early childhood is always going to peak its head through.”

It’s something that Campbell embraces by toying with, blurring the line between the secular and the religious – the world he exists and believes in, and the beliefs and moralities of the opposite line of thinking. No Closer To Heaven, for example, is not a reference to the Christian afterlife, but to the more secular reading inspired by the great and majestic stars that appear above the Great Plains of Kansas at any given time. And once again, that duality is something, once again, encapsulated within the words of Cigarettes & Saints.

“That line, ‘I lit you a candle in every cathedral across Europe’, and then ‘I hope you know you’re still my patron saint’ – I love that,” says Campbell. “I’m very obviously, if I don’t want to say atheist I would say heavily atheist-leaning agnostic – but while I don’t appreciate the actual religion, to still appreciate the tradition and the ritual of lighting a candle is an interesting dichotomy. Then to directly afterwards address my friend who died of this drug overdose as a patron saint would probably be seen as blasphemous, because obviously he isn’t a saint. So I kind of love that – embracing the ritual but not embracing the hard line of the religion in one breath.”

Yet as much as indictment of human nature’s judgmental streak, it also seeks to extract something positive from it. And that, after all, is something The Wonder Years have always strived to do. As Campbell sings on Suburbia’s Local Man Ruins Everything: ‘It’s not about forcing happiness; It’s about not letting the sadness win’. That strength of desire for positivity – or at least for subduing the reductive reductive negativity that flows through all of us – is continued here, but, like the album itself, extended and expanded beyond the hyper-personal.

“This is something that came up a lot when we did I Won’t Say The Lord’s Prayer on Suburbia…” says Campbell. “The idea to these people is that nihilism and atheism are one and the same – if you don’t believe in God and you don’t believe in an afterlife, then your whole life is this meaningless, floating display of nothing. You are a speck and you are insignificant and when you die you are dead. To them, that is the worst thing in the world. And to me, the idea of no afterlife means now there’s a time limit and I need to be actively living for this life. People talk about the meaning of life and ask what it is, and I think that’s the thing that everyone has to decide for themselves. What I’ve decided is I would like to make the biggest positive impact I possibly can on this world while I’m on it. Of course, positive is relative. The things that I think are right other people may not think are right, and I’ll probably not think some of those things I did are right when I look back at them in a couple of years, because that’s also part of growing up. And part of this record is understanding that you’re going to fuck up and when you look back at it you’re going to say ‘That was a mistake’ but that it’s okay, that you’re going to make those mistakes and you should still be trying to do better. So while some of the things I do I might look at and say, ‘Okay, that wasn’t great – you should have done this different’, instead of dwelling on that, the plan is to take that knowledge, understand that I didn’t do that particular thing the best that I could and then go out and keep trying to do good. And hopefully now I know some ways that I fucked up and I can try to not fuck up that same way again. That’s life for me.”

As complex as the constitution of *No Closer To Heaven *is, it’s the band’s most popular to date, landing at number 9 in Billboard charts the week after its release. And while that serves as some kind of validation for what the six-piece have been doing since they formed in July 2005, it also representative of a point that they make with Stained Glass Ceilings, the album’s most visceral song, which features an incendiary guest vocal from letlive.’s Jason Aalon Butler. Of all the songs on the record, it’s the one open to least interpretation – a violent middle finger and kick to gut of the way American society is configured to favour those born with a golden spoon in hand. Again, it’s no Anti-Flag, but as Wonder Years songs go, it’s pretty damn political.

“It’s a deliberate shot at American classism and racism,” concedes Campbell, “but I think that can apply worldwide as well. It’s a shot directly at the idea of bootstrapping and people who will sit with their privilege and say ‘If anyone works hard, they will succeed, and if they fail it’s because they didn’t work hard’ – and how much bullshit that is. Because that’s under the assumption that everyone is standing on the same level playing field, which is patently untrue. And I’m not saying that people shouldn’t have to work hard. Everyone should work hard, but understand that working hard is not a one-to-one ratio with success, that there are other factors involved. I think a lot of people have trouble admitting they have privilege because they feel it negates their hard work, that if they say ‘Yes, I am privileged’ that means ‘I had a free ride’. And I’m not saying that at all. In no way do I believe that. I have a ton of privilege. I am an able-bodied, straight, white, cisgender male in the middle class of America. It doesn’t really get much more privileged than that. But that doesn’t mean I didn’t work my ass off. I really, really did. I worked very hard. Saying that I’m privileged doesn’t negate the hard work that I put in. What it does is say that you understand that some people have to work even harder – and even if they do work even harder they may not have the same level of success because they didn’t start on the same ground.”

To that extent, perhaps The Wonder Years, and No Closer To Heaven in particular, stand as one of the boldest political statements of 2015. Because in a year that’s seen incredibly vital and politically-driven albums from Desaparecidos, Anti-Flag, Boysetsfire and Great Collapse – not to mention a year that’s seen Jeremy Corbyn win the Labour leadership and Bernie Sanders rise to the forefront of the Democratic Presidential candidates – it’s an album that demonstrates that outsiders *do *have a chance. They just have to fight for it, and find those willing to fight for them as well.

“I said this on Instagram,” chuckles Campbell, “but we’ve played every day of being in this band with a chip on our shoulder. We have been the perpetual underdogs, even if it’s just in our own minds. We’ve always played that way and written songs that way. We are the people that don’t belong in the Top Ten. We weren’t supposed to be there. We literally started our career as a joke and we spent the first five years of it playing basements. So it’s very vindicating. I’ve said this phrase a couple of times, but it does feel like we’re crashing a party we weren’t invited to. We’re the punk rock band that made it into the top 10. It feels really cool. I feel very re-energised. I get very doomsday-y, and I started feeling like ‘I’m going to fuck this up and that will result in this thing which will result in this thing which will result in us breaking up eventually’, but we had a top ten record and I got engaged. I’m happy and I’m excited and we want to just get out and play.”

Amen to that.

No Closer To Heaven is out now through Hopeless Records. The band tour the US in October, then the UK next February as special guests to Enter Shikari. See their official website for full details.