According to the organisers, the Erie Canal Soda Pop Festival was going to be “bigger than Woodstock”. More than 30 bands were promised for the three-day event, among them The Faces, Joe Cocker, Black Sabbath, Fleetwood Mac and The Eagles.

Things did not go according to plan, and the festival succumbed to many of the same issues that plagued Woodstock 99 nearly three decades later.

Bob Alexander (co-promoter): All we ever set out to do was to have a great show and make a lot of money. We’d spent over $700,000, so our position was that we had to do this festival some way. Come hell or high water, the people were going to have an event.

Chuck Pulin (promoter, Nazareth): The talk among groups in the east the weekend before the show was: “Will Soda Pop happen?” We didn’t know. We were entirely in the dark.

Bob Alexander: They were on WLS [Chicago radio station] every 15 minutes talking about the festival. They started spreading the word nationwide… we knew people were coming because of all the phone calls we received. They just kept talking about it. “Where’s it going to be?”

Randy Foley (audience member): We drove 450 miles, from Toledo, Ohio, in a 1965 Volkswagen Beetle to rural southwest Indiana. As we approached the festival site along Interstate 65, the road started to clog up, but we could still move.

Dick Kay (NBC News reporter): Every shoulder of every road leading to the festival, including a four-mile stretch of interstate highway, was jammed with parked cars. Rock bands decided to walk to the site rather than wait out the traffic jams.

Ed Lunkenheimer (Indiana State Police Trooper): It was like an invasion. They were bound for Bull Island, come hell or high water. We’d never seen that mass of humanity. Ever.

Carrie Jane Roper (audience member): With all these cars stopped on the interstate, there were lots of drug deals going on. There were people selling hash, LSD, anything, people just having a big party.

Ed Lunkenheimer: We couldn’t really control all the drugs. We just hoped we didn’t have too many overdoses.

Mike Glab (audience): The site lacked water, food, medical supplies, toilets… A downpour of biblical proportions soaked [us] on Friday night.

Kevin Swank (audience): As you walked in, the gate was open and outside of the fence there were all kinds of police. But once you walked through, not 10 feet in, there were all kinds of drugs for sale.

John Neidig (Indiana State Trooper): Every place you turned it was just all over the place. Anything from marijuana to heroin.

Shirley Becker (ticket collector): We only collected money on the first day. There was no hope after that. I think the promoters knew they lost control of the whole event. People were just giving me whatever they had. One guy didn’t have any money so he gave me a beer. I was delighted.

Randy Foley: Very few of the bands who were advertised actually played. The ones who did were hardly superstars. A forgettable all-female band called Birtha was first. Flash was on the bill that evening, with former Yes guitarist Peter Banks. I’d like to say I remember their performance, but I don’t. Brownsville Station and Rory Gallagher both played as well.

Lydia Woltag (artist representation): Black Sabbath were willing to work but it was impossible. It took me over four hours to drive out to the site on Saturday night. The stage, about an inch deep in water, was protected by a leaky tarp and there were exposed electrical outlets. It was simply too hazardous to play.

Mike Glab: I took a hit of Orange Sunshine that Saturday night, my first acid trip. As Foghat played I Just Wanna Make Love to You, I looked down at my hands and discovered I’d gashed them wide open. I could have sworn I saw the tendons and bones inside of me… People leaped up and ran for first aid, but when I came down I realised it was just a nasty paper cut from a guy who had been passing out flyers.

Randy Foley: It was chilly, and the waits between bands quite long. Canned Heat took the stage next, boogied for a long time and warmed things up.

Fito De La Parra (Canned Heat): We always wanted to play, no matter what the circumstances. Bob Hite, our leader in those days, he always wanted to go for it, even if we didn’t get paid. We were so high I can’t even remember if we did get paid.

Randy Foley: Cheech & Chong made some less than positive remarks about the festival, disguised as jokes. After about 15 minutes it started to rain, they said their ta-tas, and left the stage.

Sonny Brown (local photographer): By the second day, the Sunday, personal hygiene was non-existent. For waste – human waste or whatever – they just had trenches.

Mike Glab: As we bathed in the Wabash River that morning, the sounds of Ravi Shankar’s sitar wafted over us. I’ll never forget that moment, it was the first time I’d ever seen a nude chick.

Dan McCafferty (singer, Nazareth): This was during our first tour of America, and Erie Canal was our first major festival. We didn’t know until we got there that the venue had changed… there was virtually no way to get from the hotel to the site.

Bob Alexander: Rod Stewart & The Faces’ manager flew over in a helicopter and deemed that the site was not safe. We started to negotiate immediately, and nothing was concluded.

Dan McCafferty: I remember Joe Cocker turning up, and Rod Stewart, but neither of them went on. We were still young, though, and up for playing any gigs we could get, so we agreed to go on, even though things didn’t look great.

Nigel Thomas (manager, Joe Cocker): We found the performance side of the festival in absolute chaos. My road crew, which had driven our equipment to the site, found the stage unsatisfactory and unsafe and the security inadequate. We never suggested more money for Cocker [as alleged]. The only mention of $30,000 came when they asked us how much we stood to lose if we couldn’t play our next date.

Rickie Lee Reynolds (guitarist, Black Oak Arkansas): The story we heard was that Joe and his band came in on different planes. The band did the soundcheck but… When Joe landed he grabbed a cab which took him to the wrong hotel. He booked in anyway, fell asleep, and when he woke up it was already too late to go on stage. While we were at the hotel, some of the bands decided not to even go to the festival site. They were afraid of rioting.

Randy Foley: Late at night, Ted Nugent and the Amboy Dukes played. Though an impressive guitar player, Ted always over-compensated with his own brand of flash and patter and jive.

Dan McCafferty: On the third day, the Monday, the organisers said they would get us into the festival by helicopter… A free helicopter ride, yeah, why not? But when we got backstage there were almost no facilities, no toilets, nothing.

Randy Foley: From the stage, announcers promised acts that never appeared and people were getting out of hand. Debris started flying between the audience and the stage.

Rickie Lee Reynolds: The police were freaking out and security got pretty heavy because there were little riots going on at various spots, people getting rambunctious.

Randy Foley: The Doobie Brothers drew mixed reactions from the massive crowd. Nazareth got a more positive response.

Dan McCafferty: We were determined to put on a good show, and we did, but we could see that beyond the first few rows of kids who were enjoying the music… things were bad. When our helicopter took us back to the hotel, we had a wee girl, a teenager, flying with us. She was completely out of it. Didn’t know where she was, didn’t know where her friends were. She had obviously taken something that didn’t agree with her, and she was pitiful to see.

Randy Foley: The final band of the evening was Black Oak Arkansas.

Rickie Lee Reynolds: Our plan had been to get a flock of white doves in crates under the stage, and set them free just as we hit the last note of our set. Unfortunately, when we arrived there were no white doves. The road crew had searched around for an alternative and came back with three dozen pigeons. Then we released the pigeons. But we didn’t know pigeons wouldn’t fly in the dark. Instead they headed for the lights of the stage… walkin’ around, looking like Charlie Chaplin, y’know? I had one on my guitar neck, Jim [Dandy, frontman] had one on his head… I would shake that pigeon off my guitar but it would fly round and land again. The crowd thought it was part of the act.

Randy Foley: The crowd roared… wanted, demanded, more.

Tom Duncan (co-promoter): We were afraid to tell them it was over… just couldn’t be sure what would have happened.

Randy Foley: After a lull, the announcer said there was no more. None of the big-name groups had showed up, and the riot from earlier seemed to pick up where it left off. We got out of there pronto. Eventually the stage was looted and burned to the ground. As we headed back to our VW, we saw people looting cars and vans, stealing gas and wheels off vehicles.

Bob Alexander: We had a helicopter backstage, and we had them fly us back into Evansville. And we started dealing with the problems – paying people off… Probably the biggest mistake I made as a young man was that I didn’t know how to manoeuvre within the political system.

Fito De La Parra: It was the biggest disaster we ever played, but I still have a certain sympathy for the promoters. They were just trying, as so many people have done, to create another Woodstock.

Bob Alexander: The mere fact that we’re talking about this 40 years later says something about it as a major cultural event that happened in Middle America. You know, I’d love to try it again, in the same location.

What happened next?

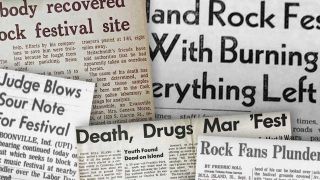

Bob Alexander estimates that the Erie Canal Soda Pop Festival lost $200,000, with lawsuits continuing for nine years. One local farmer even sued them for “cattle lost due to marijuana inhalation”. Tragically, it later emerged that there had been two deaths - a 24-year-old man who drowned in the Wabash River and a 20-year-old who overdosed on heroin.

Alexander is currently president of the Motion Picture Hall Of Fame in Palm Springs. Festival co-promoter Tom Duncan concluded that rock festivals were not “morally right” and retired to Arizona. Attempts have been made in recent years, without their involvement, to re-stage the festival but so far without any concrete results.