Since it was established in 1967, the Montreux Jazz Festival has been one of the most iconic events in the rock calendar, with everyone from Jethro Tull, Queen, Aretha Franklin, Frank Zappa and Deep Purple taking the stage in the Swiss city. As one of its founders, Claude Nobs – aka ‘Funky Claude’ – was central to the festival until his death in 2013 at the age of 76. In 2006, Classic Rock sat down with Nobs to look back on the illustrious history of Montreux, his friendship with Led Zeppelin, and the true story of Smoke On The Water

‘We all came out to Montreux, on the Lake Geneva shoreline…’

So begins the opening line of the classic rock songs. Deep Purple’s Smoke On The Water tells how the band came to record their Machine Head album in December 1971; how they planned to record at the Montreux Casino using the Rolling Stones Mobile, only for the building to burn down the night before when ‘some stupid with a flare gun’ fired into the roof during a concert by Frank Zappa & The Mothers Of Invention. It’s a tale that has passed into rock’n’roll folklore.

Midway through the second verse Ian Gillan sings: ‘Funky Claude running was in and out, pulling kids out the ground’. The ‘Funky Claude’ in question was promoter Claude Nobs, who had set up the whole recording venture, and rescued it from disaster after the fire by moving the operation to the nearby Pavilion Theatre, where Purple managed to rattle out the basic track for Smoke… in one evening before the police arrived in response to a torrent of complaints from the citizens of Montreux whose quiet neutrality was being shattered by the noise. Funky Claude moved them again, this time to the deserted Grand Hotel outside town, where they created another makeshift studio in the corridor and adjoining bedrooms.

Not many promoters find themselves immortalised in song, let alone a song that has become a legend. But Claude Nobs is more than a promoter. Few artists turn down the chance to play at the now famed Montreux Jazz Festival he stages every year, however big those artists have become. And they’re not doing it for the money.

When Nobs co-founded the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1967, it lived up to the ‘Jazz’ part of its name, reflecting his first musical passion. In 1969 Ten Years After and Colosseum signalled the arrival of electric jazz and blues, and the following year Santana broke new boundaries. In 1971 Family were the first rock full-on band to appear (the same year Aretha Franklin made her debut).

But it was Smoke On The Water that introduced Montreux to a wider audience. Nobs can remember the first time he heard a rough version of the song, in December 1971, “I was cooking them supper every night, and one time they brought a tape and said: ‘Claude, we did a little thing for you but we don’t know if it’s going to make the album.’ They played it to me and I said: ‘What do you mean?! You’re crazy. This is the single.’ And they looked at me and said: ‘Do you think so?’”

Purple bassist Roger Glover recalls that when the band checked in to their Montreux hotel they each found in their room a T-shirt from a recent show, a basket of fruit, a bottle of Swiss wine and a pass to see Zappa’s show at the Casino. So they all went, and got an eye-witness view of the whole débâcle. Just don’t ask them who came up with the song title. All these years later they’re all claiming it.

The welcoming gifts in their rooms were typical of the hospitality that Nobs started with Led Zeppelin, a band not best-known for their benign attitude to promoters. Zeppelin never played the festival, but they performed at the genteel resort on each of their three European tours, even when they were filling out arenas and stadiums across Italy and Germany. And in 1972 they played their only European show of the year there, warming up for their British tour.

“I first saw them play at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1969,” Nobs says of Zeppelin. “I was with the guys from Atlantic and I met them afterwards. Later on I went to London to see their manager Peter Grant and brought a bottle of Black Label whisky I’d got at the Duty Free shop. He said: ‘This is the first time someone ever gave me something before asking for something.’ He was so surprised, that we did a deal. And the deal was that I had no contract. Peter just said: ‘Make the boys happy.’”

It was the start of another friendship that has lasted beyond the life of Led Zeppelin, and was sealed forever one traumatic night in August 1975: “I got a call in the middle of the night from Jimmy Page, who was very upset. He said: ‘Robert and Maureen [Plant’s now ex-wife] have had a terrible car accident in Greece and we need help. I’ve tried calling Atlantic but there’s nothing they can do.’ I told him: ‘You need to jet from London with a doctor so that they can bring everybody back.’ So I organised that for them and put up the money.”

Plant’s injuries kept Zeppelin off the road for the next 18 months. In September 1976 Page and John Bonham showed up in Montreux during a nomadic year spent wondering the globe in tax exile from the UK. But Nobs being Nobs, and Page and Bonham being Page and Bonham, it wasn’t long before they found themselves in a local studio.

The result was Bonzo’s Montreux, a drum solo with electronic effects added by Page. It wasn’t right for the Presence album the band were working on at the time, but it eventually emerged on 1982’s Coda, credited to ‘The John Bonham Orchestra’, where it was a fitting epitaph to the drummer.

That wasn’t the end of their association with Montreux, however. In 1993 Plant played a solo show at the festival, and in 2001 Plant & Page were part of tribute to Sun Records, belting out Good Rockin’ Tonight, My Bucket’s Got A Hole In It, Candy Store Rock, My Baby Left Me and Baby Let’s Play House. In 2006, Plant turned up at the festival again, this time to take part in a tribute to Atlantic Records’ executive Ahmet Ertegun, who first introduced Nobs to Led Zeppelin at the Newport Jazz Festival in the US back in 1969 when Nobs was looking for jazz artists to take to Montreux. Plant sang songs by Joe Turner and Ray Charles, in the company of Chaka Khan and Stevie Nicks and a house band that included Steve Winwood and Chic’s Nile Rodgers.

It wasn’t just Deep Purple and Zeppelin who had a relationship with Montreux. Jethro Tull liked Claude Nobs so much that in 1972 they relocated to the town in an attempt to keep hold of more than the 15 per cent of their income than the British Government would allow at the time. Tull mainman Ian Anderson even became a Swiss resident, and chunks of the band’s Passion Play, War Child and Minstrel In The Gallery albums were written and prepared amid the fresh air and mountain scenery around Lake Geneva. In return, Tull donated the proceeds of a 1978 Bern concert towards the building of a public library in Montreux. The show was recorded for their Bursting Out album, on which Nobs can be heard introducing the band. Anderson dedicated the remastered CD to “Claude Nobs, the Jazz Festival and the little town of Montreux in return for so many happy moments”.

The Rolling Stones were already too big to play the festival when Nobs launched it in 1967, but they were his first significant promotion three years earlier when he persuaded the producers of top British TV pop show Ready Steady Go to broadcast the show from Montreux with the Stones and Petula Clark (back then Petula was a worthy coheadliner, particularly in Europe).

“I was giving away free tickets outside the Casino, and people were looking at them and going: ‘The Rolling what?’ says Nobs. “And then the producers didn’t want to have the Swiss crowd standing near the band because they looked so square; the boys had short hair and the girls had long dresses. I saw the band in Zurich on the latest tour a couple of weeks ago and we were laughing about it.”

In fact just about the only big British name Nobs was unable to promote during the 60s was The Beatles, and even that was not his fault. “In 1963 I was working at the tourist office, and I was looking for some acts to play at the Golden Rose Of Montreux TV show. I went to London and found The Beatles’ office, and by luck they were there. They were happy to do the show. So I went back and told Swiss TV, and they said they weren’t well known enough yet.”

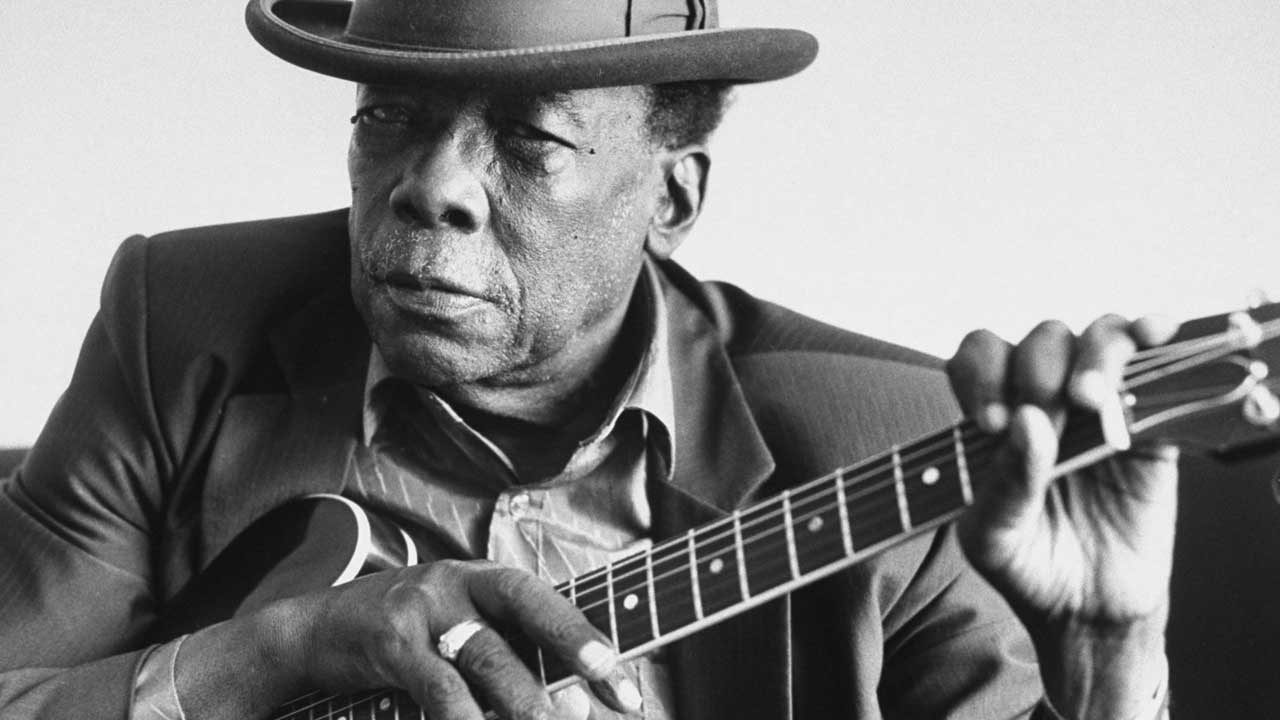

Rock got a foothold in the festival in the 70s, but jazz and blues continued to dominate through the 70s, with occasional flurries of singer-songwriters, folkies, reggae singers and solo appearances from Rick Wakeman and Steve Howe The 80s were suitably eclectic (Marvin Gaye, Jimmy Cliff, The Specials and Steve Hackett in ’80, Mike Oldfield, James Brown and The Stray Cats in ’81, Steve Miller, Talking Heads and Mink DeVille in ’82), although the 1987 line-up that included The Christians and T’Pau was probably taking it a bit far.

Rock started taking a re-asserting itself grip in the 90s, kicking off with Sting, Little Feat and Was Not Was. White blues was also in the ascendency, with Eric Clapton backed up by Jeff Beck, John Mayall, Rory Gallagher, Jeff Healey and Gary Moore. But when Paul Rodgers was joined by guest guitarist Brian May in 1994, it started off a chain of events that led the former Free/Bad Company singer joining forces with May and drummer Roger Taylor in a retooled version of Queen, named Queen + Paul Rodgers.

By the late 90s, revived supergroups of the 70s like ELP and Supertramp were appearing at Montreux. In 1998 Bob Dylan showed up, and there was a delightful Irish quartet of Bob Geldof, Mike Scott, Van Morrison (who is almost a regular). Factor in appearances from The Corrs, Björk, Deftones, Iggy Pop, Morrissey, Carlos Santana, Massive Attack and countless others, and the breadth of Montreux becomes apparent. And Deep Purple? Ironically, the band who immortalised the festival didn’t actually appear at it until 1996, though they’ve subsequently made another seven appearances. Throughout it all, Nobs’ approach has remained the same.

“For me the artist is the priority. It’s as simple as that,” says Nobs. “If the artist is happy then the crowd will be happy, and I will have fulfilled what I have to do. It’s not about the money. These people can get plenty of money at other places. It’s about the freedom that they have here and the hospitality that they don’t seem to get anywhere else.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 98