With their air of medieval folk metal, songtitles alluding to Arthurian legends, shifting time signatures and the singer’s startling, shrill voice, Pavlov’s Dog were arguably America’s first prog band. Sadly, they didn’t quite do the business of their Brit prog counterparts, and after a striking debut album, their music became more mainstream and streamlined, closer to AOR, only latterly returning to prog pastures.

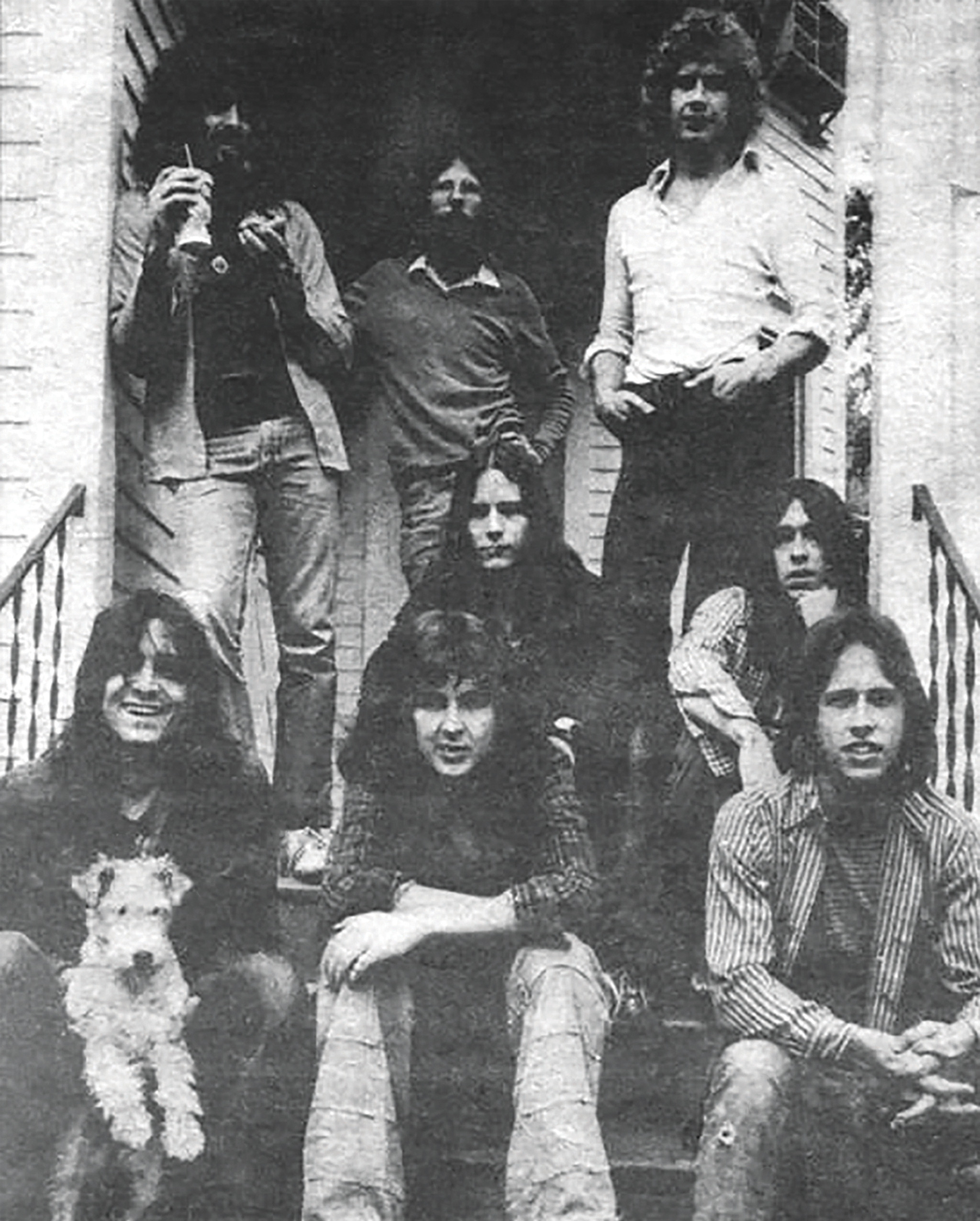

Still, for a while, Pavlov’s were Very Prog Indeed. They had members of King Crimson playing with them and they shared an engineer with Meat Loaf. Their frontman, David Surkamp, a cult figure of mythic proportions, can even detect their influence in the prog of today. But when they emerged, straight outta St Louis in 1972, with their seven musicians including a violinist and a flautist/mellotron player, according to Surkamp, “Nobody had heard anything like us.”

When Prog asks what sort of reaction they got from audiences, his answer is simple: “Astonishment.”

Pavlov’s Dog’s story starts with the band High On A Small Hill, which Surkamp formed in 1971, aged 19, with bassist Rick Stockton and two other high school friends. Surkamp would write songs on his acoustic guitar to try to impress local beauty Sara (now his wife). He had always been musical, playing the ukulele, mandolin and piano when he was four or five. He says he never thought his singing style “was that different” – a strange thing to say, perhaps, about a voice that has been compared to everyone from a hyped-up Geddy Lee or Edith Piaf to “a choirboy on speed”.

High On A Small Hill acquired two new members – Sigfried Carver on violin/viola/Vitar, and Mike Safron on drums – then changed their name to Pavlov’s Dog.

They were heavily influenced by King Crimson and Fairport Convention. “I was coming back from high school and went into the drugstore and saw In The Court Of The Crimson King and bought it because I liked the cover,” Surkamp recalls. “I remember hearing those foghorns at the start of 21st Century Schizoid Man – that was it for me. I loved Fairport Convention, too – they were probably my favourite band. But if you listen to that first King Crimson album: Moonchild, I Talk To The Wind… those are kinda folk songs. Just the saxophone and guitars set them apart.”

Pavlov’s lyrical preoccupation with Ye Olden Days – titles such as Episode, Preludin and Of Once And Future Kings – came from Surkamp.

“My grandmother was into Shakespeare,” he says. “She used to be a performer with a lovely singing voice and she was interested in children’s ballads and Elizabethan stuff, and that rubbed off on me.”

A childhood illness also had an impact on Surkamp. “When I was five, I guess I was nearly dead,” he says. “I was born with asthma, had frequent bouts of pneumonia and needed these allergy shots two or three times a week. I was so panicked and miserable. So my dad gets on the phone and starts calling round the world to find a boarding school in a decent climate that would take a five-year-old, and this operator said, ‘Oh, my sister is a Sacred Heart nun and they have a reservation school outside Tucson.’ So he called and apparently the nuns said, ‘Bring him down,’ and there I was, on the outskirts of the desert.”

There, “sick all the time”, the young Surkamp immersed himself in fantasy literature. “All I did was read,” he explains. “I read all the Sherlock Holmes and Tarzan books, the Grimm’s fairy tales, the Arthur stories… I had nothing else to do.”

If Surkamp was accruing a love of the fantastical at his first school, once back in St Louis, he got used to being an outsider at high school and took matters into his own hands.

“St Louis is a real backwater place, full of ignorant people, and I had hair down to my elbows and wore white clogs so I became something of a target,” he admits. “I soon learned to protect myself. One day, these students thought, ‘We’re going to beat up this hippie,’ and that didn’t work out too well for them.”

Playing gigs as Pavlov’s Dog was equally hairy, surrounded as they were by Lynyrd Skynyrd types. “All there was was white guys playing the blues – really pathetic,” Surkamp sneers.

Hence the somewhat negative reaction they would often face. “Occasionally we would play hostile environments and the girls would be hitting on us and the boys would want to kill us,” he laughs. “They hadn’t seen long‑haired boys playing really loud music with lots of time changes before. You couldn’t dance to it.”

In 1973, the band spent three days cutting a series of demos – later released as The Pekin Tapes – “in a studio in the middle of a cornfield in Illinois”. A local radio station began playing one of the tracks, Theme From Subway Sue, and that’s when record labels started calling. ABC offered them $650,000, an unprecedented sum for a new band.

Did the label think they had the American Genesis on their hands? Surkamp isn’t convinced.

“See, Genesis weren’t very big then over here so I wouldn’t have said that for sure, and Crimson were considered a failure. But what we did have was a reputation that you didn’t really want to follow us as a live act. Kiss wouldn’t play on a bill with us – they were afraid of being blown offstage – and Aerosmith dropped us after two nights.”

One band who didn’t fear them were Blue Öyster Cult, the cerebral metal band. The two outfits soon became friends, and Pavlov’s even acquired their production team of Sandy Pearlman and Murray Krugman.

“I was familiar with Sandy from his writings for Crawdaddy [magazine] – he was a smart guy, with a sense of literature and music. I think the label approached Todd Rundgren and he said, ‘This is the most horrible shit I’ve ever heard.’ But Pearlman was the perfect fit.”

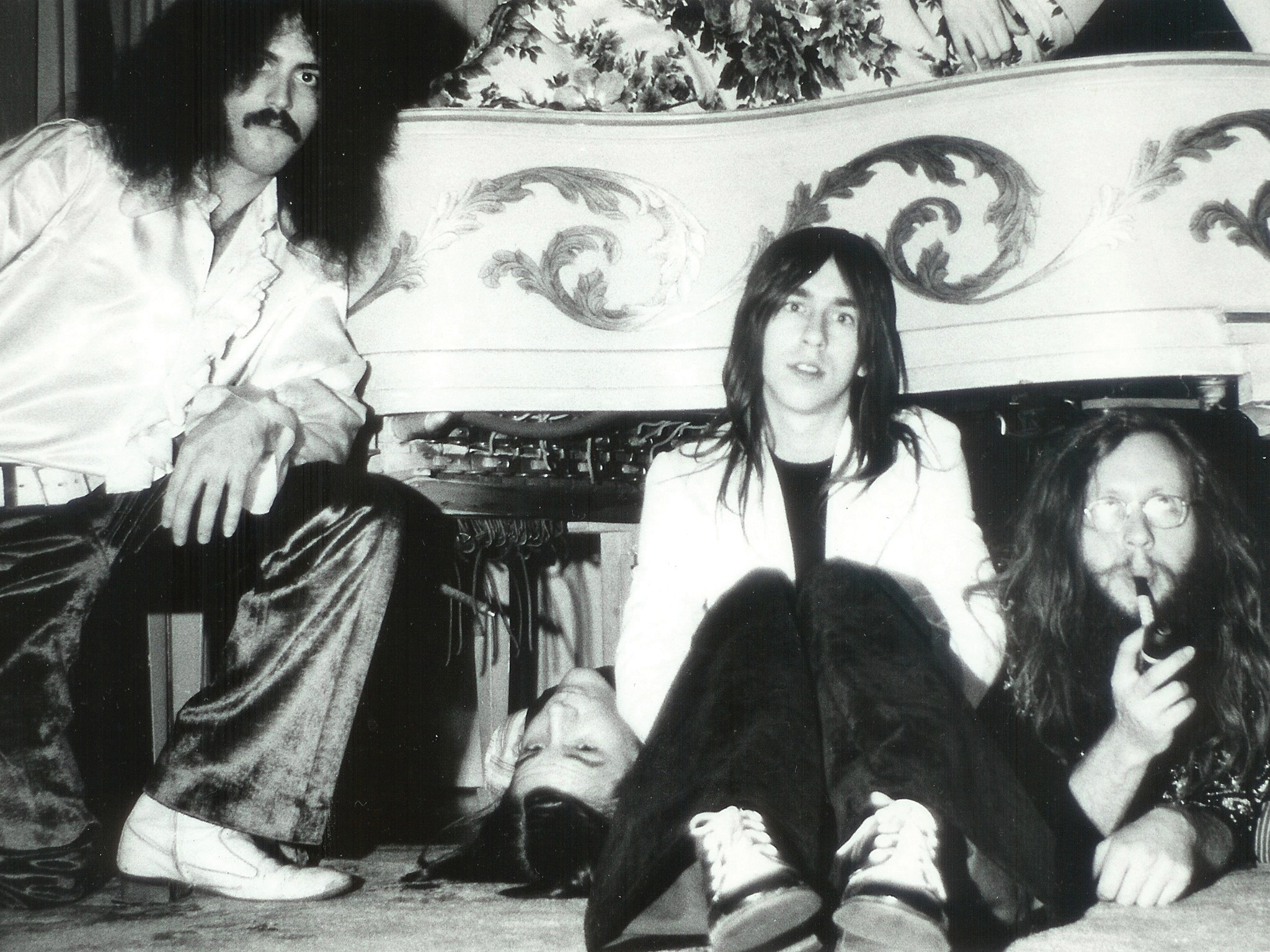

The sessions for debut album Pampered Menial took place in winter 1974, in New York. This was a city to which some of the band – now a seven-piece, including Doug Rayburn and David Hamilton on keyboards, and Steve Scorfina, formerly of REO Speedwagon, on guitar – had never been. “We were staying in the worst hotel you’ve ever seen. There’d be hookers in the lobby and you’d hear pimps beating up women in the middle of the night down the hall,” Surkamp recalls with a shudder.

The tone for the music was set by the opening ballad Julia (written at Surkamp’s parents’ house in St Louis in the aftermath of their divorce) and second track Late November, and it was wintry and desolate.

“I do like melancholy,” Surkamp says, when asked about capturing that mood of icy despair. “We recorded the album in December. I remember living in my motorcycle jacket and the promo pictures were of us in Soho and Greenwich Village in winter attire.”

The response to Pampered Menial was feverish, albeit more so in the prog-receptive UK than in the US: “Only rarely does a completely unknown, unhyped band burst into our befuddled consciousness with a first album of such sheer intensity,” wrote NME’s Max Bell in June 1975.

Does Surkamp imagine Messrs Rundgren, Steinman and Loaf heard it ahead of recording that other classic album of histrionic, quasi-operatic 70s rock, Bat Out Of Hell?

“I have no way of knowing, except that John Jansen engineered [second Pavlov’s album] At The Sound Of The Bell and he also engineered Bat Out Of Hell, so I guess it’s likely.”

Does Surkamp ever detect his influence in other artists’ work? “I do hear stuff,” he muses. “There’s some stuff Steven Wilson’s done where I assume he’ll have heard what I did.”

Surkamp finds it hard to choose between the first two extraordinary Pavlov’s Dog albums (“It’s like asking which of your children is best”), but he does describe 1976’s At The Sound Of The Bell as being “more mature”.

“On Pampered… we did some crazy stuff, just ’cos we could,” he says. “Like, do you really need to hit a high C, like I do on …Subway Sue? Probably not, but I could so I did. And the strange tempo halfway through Of Once And Future Kings? We just really liked playing in different time signatures!”

ATSOTB had its moments of proggy, jagged abandon – Gold Nuggets, Did You See Him Cry – as well as aching ballads Standing Here With You and Mersey. It also featured Bill Bruford on drums, Andy Mackay of Roxy Music on sax and Elliott Randall of Steely Dan on guitar. Did Surkamp feel an obligation to commercialise their sound given that Pampered Menial was more of a critical than actual hit?

“No,” he replies. “What happened was, the band was falling apart and the infighting had got to us. The band were all wanting to be songwriters but none of them could write! I remember sitting with Sandy Pearlman and Doug Rayburn and trying to rehearse and I said, ‘I just can’t do this any more – this is just awful.’ I was so depressed I just couldn’t take it. I hated every waking moment.”

The problem as he saw it was that the members of Pavlov’s Dog “were never friends and we didn’t get along, most of us. It was kind of Rick and I in one corner and someone else in another corner. David was more interested in trying to get his Scottish girlfriend to stay in the country than he was the music”.

By the time it came to write the next Pavlov’s Dog album, Surkamp reveals, “I was doing my best to quit.” The band’s manager decided to put Surkamp in a hotel room with a bunch of equipment (Mellotron, ARP String Ensemble) and one of the road crew to push ‘record’, and that became the third album that never was: the label refused to release it, and it only appeared as a bootleg during the 80s.

It finally got an official release in 2007 as Has Anyone Here Seen Sigfried? (referencing early violinist Sigfried Carver). By this time it had accrued almost as mythical a reputation as Big Star’s Third.

Surkamp himself became the subject of rumour and hearsay. Some even suggested he was dead, prompted by a track on …Sigfried? by the name of Suicide, and the air of exquisite gloom that always hung over Pavlov’s Dog.

Surkamp can see the funny side today. He recalls the time a German crew came to the Lorelei festival in 2005 to film a reactivated Pavlov’s Dog, assuming his 14-year-old daughter Saylor was now the band’s lead singer.

“They asked her, ‘How does it feel to be singing the music of your late father?’” he laughs. “She said [innocently], ‘My daddy’s never late.’”

They persevered, enquiring, “Since your father passed away and you’re performing your dad’s music, how does that feel?”

Meanwhile, Surkamp was very much alive, standing 10 feet away at the back of the venue, chatting about guitars with “two of my friends and heroes”, Steve Hackett and Kim Simmonds of Savoy Brown.

Surkamp didn’t take his life back in ’77, but he was desperate to escape. So he left St Louis where “a fake Pavlov’s Dog who sounded like Molly Hatchet” did the rounds, and headed for Seattle. There, he joined forces with Iain Matthews and formed Hi-Fi, with whom Surkamp had “a couple of the best years of my life” – even the time they supported The Beach Boys.

“It was like an insane asylum – it was Brian Wilson’s comeback tour and he had that shrink [Eugene Landy] with him. Brian was kind of like a zombie and it was very weird to be around him. It was supposed to be a drug-free tour and Dennis [Wilson] was obviously doing a lot of hard drugs… I was pretty naïve, and these guys had been hanging round with [Charles] Manson.”

Surkamp briefly reformed Pavlov’s Dog in 1990 for fourth album Lost In America, but the sound was too slick, closer to AOR than prog. He’s far happier with album number five, 2010’s Echo & Boo, which is closer to prog Dog than any of their albums since ATSOTB, especially drone experiment We Walk Alone Forever. It also includes such cheery ditties as We All Die Alone and I Don’t Need Magic Anymore. “Yeah,” deadpans Surkamp, “real laugh-a‑minute stuff.

“I love every moment of Echo & Boo,” he adds. “That’s my favourite record.”

The album, and the latest incarnation of the band (featuring all new, young players – of the original members, Carver died in 2009 and Rayburn in 2012) finds Surkamp at his happiest. “This is the real Pavlov’s Dog that I always had in my head,” he says.

The band’s loyal fans are equally ecstatic. “We headlined this festival in Germany a few weeks ago and when I walked among the audience, I felt like St David,” Surkamp gasps. “When we were in Prague, this guy kept screaming, ‘Maestro! Maestro!’”

Then there were the boorish Italians shouting for that most delicate of hymns, Julia, as though it was a tub-thumping footie anthem.

“Yes, that was a bit weird,” says Surkamp, recalling the gig in question. “I think they thought they were at a Queen show shouting for We Will Rock You. But our music doesn’t quite fit that, does it?”

See the Facebook page for more information.

YOUR SHOUT

They took their name from a canine-based experiment. That sounds pretty progressive to us. But how prog were Pavlov’s Dog, really?

“I would say yes, they is the prog… and they’re from my hometown!” Charles Moss

“More prog than Moebius Cat, but less prog than Henry Cow…” Stephen Boden

“They played Mellotrons. Of course they were prog.” Graham Smith

“The most prog you can get! Their albums and especially their first were meant to be prog not in a narrow way but on a wider meaning. Prog is not only lengthy tracks with neverending solos. The real meaning of prog is to bring something different, new and fresh with real passion and with their first albums they played like no one else!” Nick Papadopoulos

“PROG.” Robert Mills

“They’re no Rush. It’s more like hard pop, and I give it prog level 2⁄10.” Dave Muller

“They’re not prog in my opinion but I enjoy listening to them as I enjoy listening to Porcupine Tree or Rush. They are 10⁄10.” Luis Relative

“A wee bit.” Tony McGinley

“Definitely prog.” Jacques Jazzer

“Very.” Ian Roy Simpson

“Beautiful prog, The Enid meets PFM. Bring back the good old days…” Richard Wood

“50/50. Bill Bruford on the second album, nuff said.” Andy Slater

“Are you joking? Every track drenched in Mellotron. As prog as… er… a very prog thing!” Andrew Buckley

“Absolutely, Pavlov’s Dog was and is total prog.” J Lo Sanchez

“Did You See Him Cry is the most proggy in the original sense. Very proggy in the wider sense of the term.” Andrew Hamer

“Just YouTubed it… I like that sound. IMO: prog!” Andrew Black

“I always said, ‘Yes, they were prog’, but after more listening, I think they fell into a different category of ‘anti-pop’. They tried very hard to be taken seriously but were a bunch of musos just trying to be different. Less prog, more classic rock with a twist.” Terry Cunnett

“Can’t stand his voice.” Jeff Lee