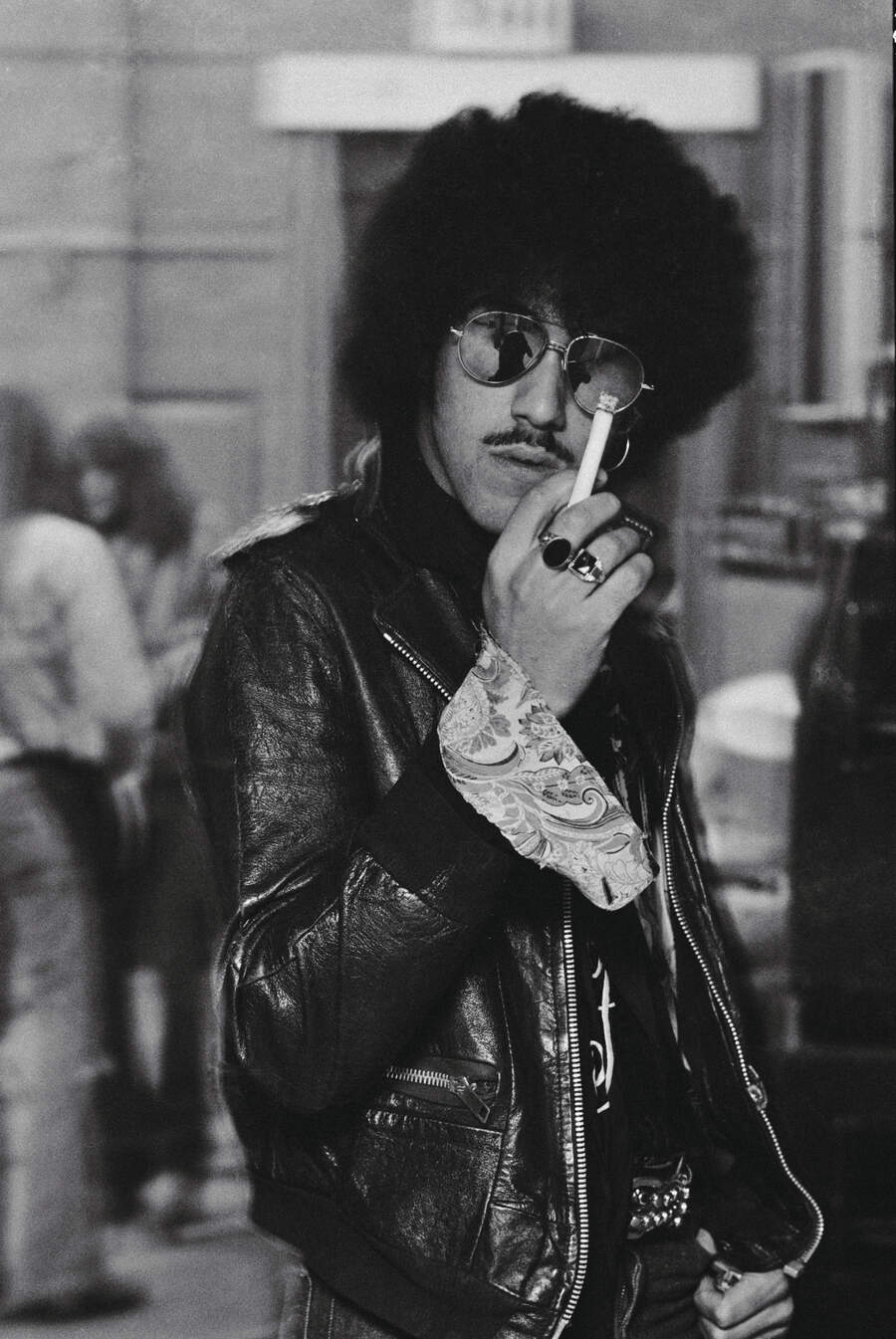

It was raining as I drove west along the A40 motorway that December morning. I was on my way to meet with Thin Lizzy to talk about recording a new album. They had been writing and rehearsing new songs in a residential studio facility situated almost 20 miles west of London. It would be the last day they would all be together before everyone left for the Christmas break.

There was a song they were unsure about, but they played it for me anyway. It was very basic, just an idea and a chord structure that set it apart from all the other songs I was to hear that day, but even then I knew I was listening to something you might wait a whole lifetime to hear. That song would become The Boys Are Back In Town.

As I drove home, I thought back to a conversation I’d had with Philip [Phil Lynott], almost a year ago, when he asked me what it was going to take for Thin Lizzy to make it in America. I told him that he needed a song that as soon as people hear it on the radio, they know it’s Thin Lizzy. Was it possible that I had heard that song today?

I’d had a recent late-night phone call with Mike Bone, the new head of radio promotion at Mercury Records. He called to tell me he was getting airplay on Wild One, a track from the current album Fighting, and that it was beginning to sell in the markets where stations were playing it. The message couldn’t be any clearer: if the company was going to get behind the band, Bone needed a track on the new album that he could take to radio.

In the unlikely setting of a rundown housing estate in Battersea, South London, was a recording studio owned by The Who. It was here that the band began working on a new album at the beginning of January 1976 with producer John Alcock. You needed a big personality to work with Thin Lizzy, and Alcock had that in spades. He also had a clear idea of the record the band needed to make. I would stop by the studio most days and sit in the control room. This was not the tentative band of the previous albums I was listening to; here was a band playing with complete confidence.

By the second week of February there was a finished album playback, and the first track I heard was Jailbreak. I remember sitting there in the control room thinking it was a game changer. I was due at Phonogram Records the following day, and I couldn’t wait for them to hear it, especially as Nigel Grainge [A&R head] had shown an incredible amount of faith in allowing us to make a third album, given we had sold very few records. He told me much later that he had been under pressure to drop the band and draw a line through the outstanding debt to the company. In reply he’d told them he wasn’t about to drop a band he believed in. When I asked him what gave him this belief, he simply said that when he’d heard an early version of the song Still In Love With You at our first meeting, he could hear what a talent Philip Lynott was as a songwriter.

We sat in his office that morning, and from the opening chords of Jailbreak it was obvious that his faith was about to be repaid. As the last note of Emerald faded, he was already calling people about the album.

A week later I was on my way to Chicago to meet with the record company, to talk about the album and set a date for its release. I called Mike Bone to let him know I was in town and would come by the Mercury Records office. He had organised a playback of the album for the company, which they had heard great things about from Phonogram Records in London. They weren’t disappointed. Mike looked at me and said: “The Boys Are Back In Town - that’s the single,” and I agreed. This was the track he would take to radio.

Afterwards, he dropped me back at the hotel. And as he drove off, I knew then that if Bone was working the record, it was going to get the promotion it deserved. I had one more meeting scheduled on this trip, and that was in New York to confirm a tour in the US to coincide with the album’s release there.

The tour was confirmed to begin mid-April. After my meeting, I had some time to kill before I had to leave for the airport. The only way to know a city is to feel it beneath your feet, so I walked everywhere rather than take a cab. I walked from the office of Mercury, down through Times Square and along Broadway, until I reached Greenwich Village. I stopped for a coffee at Café Reggio on MacDougal Street, and I could hear a tape of Miles Davis playing in the background.

As I looked out at the passers by, I thought about my meetings. We had a new album, had chosen the single, and the band were now confirmed for a tour of America. I thought about the impending release of Jailbreak and the myriad reasons why it had to be a hit, because it really was the band’s last roll of the dice.

The album’s sleeve was designed by Jim Fitzpatrick in collaboration with Philip, based on a sci-fi concept about breaking free from all forms of control and authority. The release date was set for Friday, March 26, and from the moment we had delivered the album to the record company, everyone believed this was the record that would be the success the band had promised for so long.

The following week I was in the office on Dean Street in Soho. This was the day we would hear from Phonogram with a chart position for Jailbreak. Co-manager Chris Morrison and I sat there, trying to predict what that position would be, but we had no idea. The hours dragged by, waiting for the call. When the phone finally rang, it was A.J. Morris, the managing director of Phonogram, ringing to say that Jailbreak had entered the chart as the highest entry that week. “Twelve,” he said. “The album is number twelve. Congratulations to you and Chris Morrison and the band.”

The excitement we felt that morning was palpable. My phone rang and it was Philip. He wanted to know if what he had heard about the album was real, and whether it would mean a change of fortune for the band. He and I both knew he wasn’t actually ringing about the news from Phonogram, he wanted to hear what my ambition for the record was, and that meant the release of the album in America and the upcoming tour. He listened to the conviction in my voice, and he never made that call again.

The last couple of years had been a constant struggle in terms of raising money to keep the band and the office financially viable. We owed money to the bank, finance companies, suppliers and just about everyone else. For us, the success of the album meant some breathing space and a way to start paying off some debts. As I switched off the lights, it would be the last time I would be in the office for three months, as in a couple of weeks we were flying to New York to begin the US tour. America was about to hear that the boys were back in town again.

There was an urgency to the band’s arrival at Heathrow airport that morning. It was the first time that they were beginning to get noticed. How different to that morning over a year ago when they were about to depart for their first ever tour of America. I was waiting for them at the check-in desk with their tickets and passports. Once again the American Immigration Department had delayed us in getting our visas and work permits. I had waited in a queue at the American Embassy from the early hours of that morning to see if they had been approved overnight. Thankfully, they had. I had the stamp in the passports that allowed us to board a plane and work in the United States.

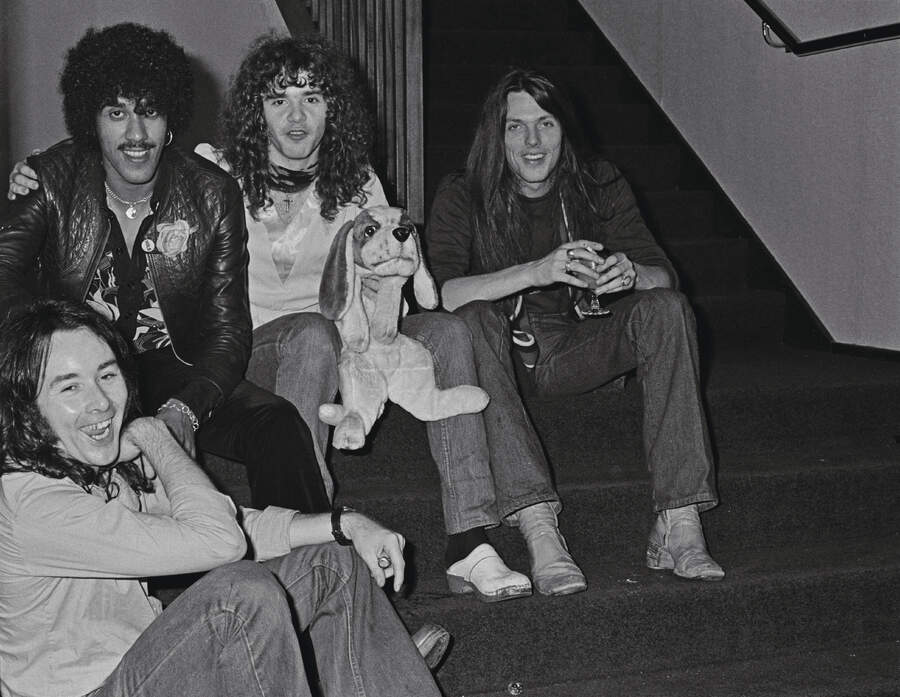

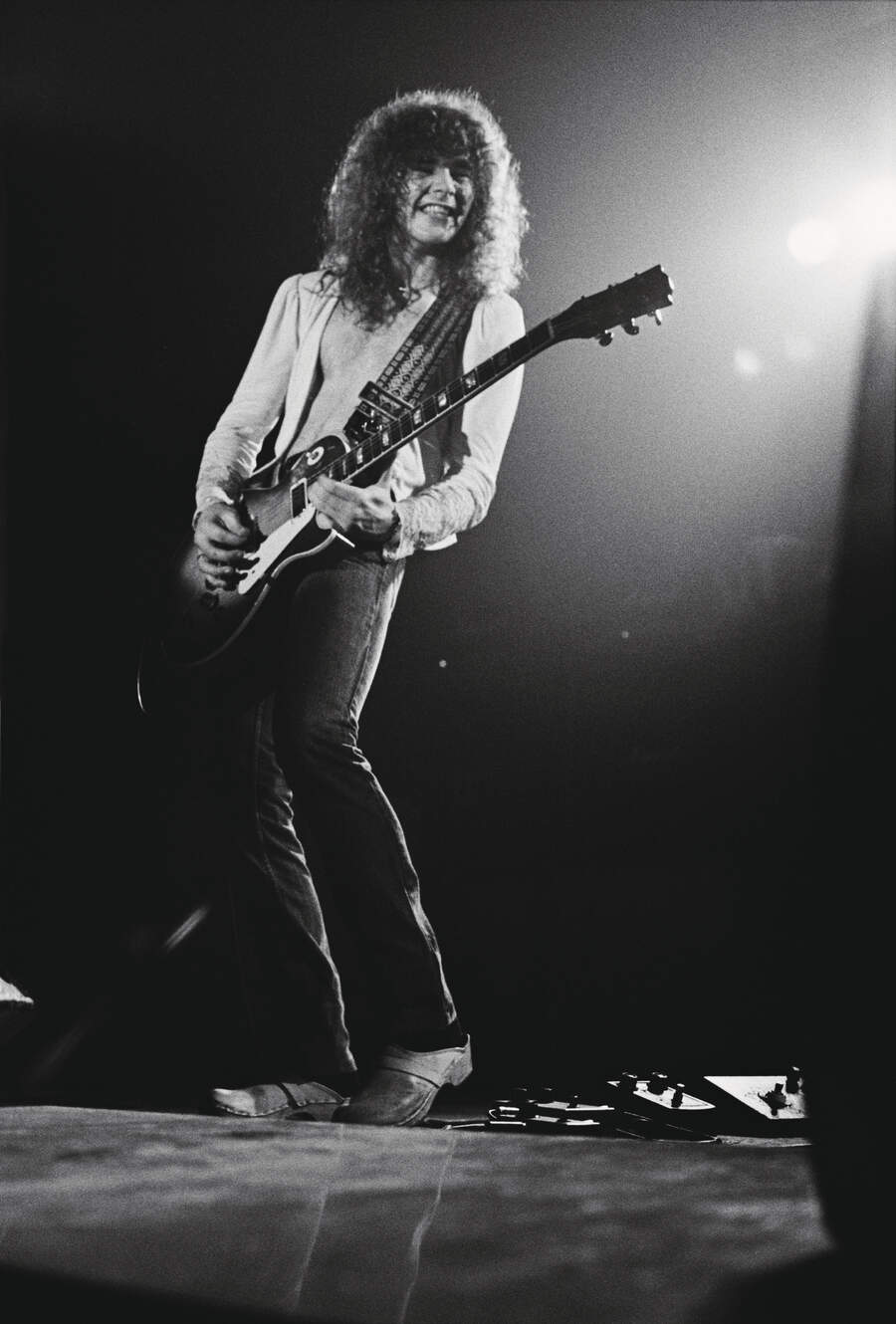

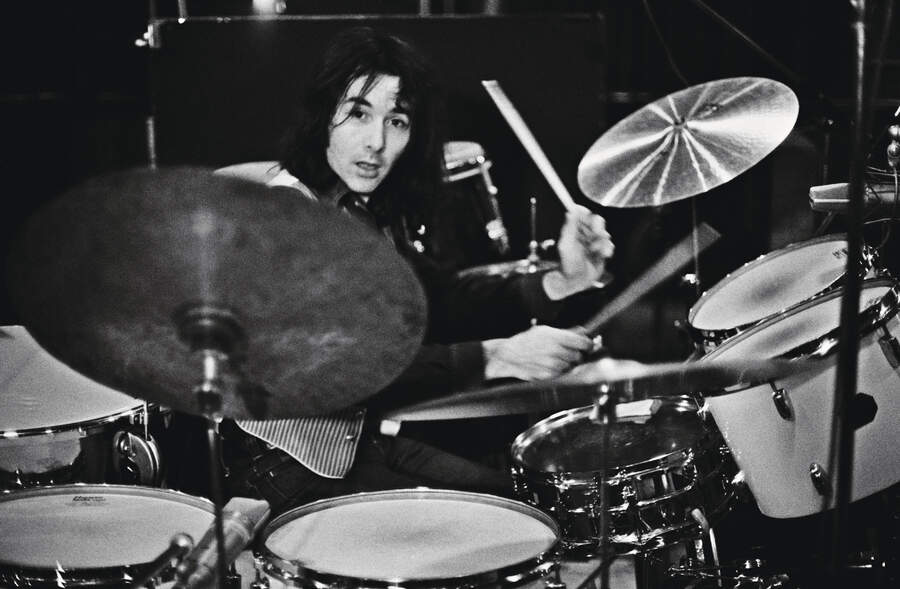

As we waited in the TWA lounge, I talked with Scott Gorham, who told me how excited he was that there was a Los Angeles show on the run. It meant a lot to him to be returning to California as part of a successful band. Philip was laughing with Brian Downey about something they had heard from a friend back home in Dublin, and Brian Robertson was talking to his girlfriend on a pay phone. The next six weeks were going to be interesting. We left London with the knowledge that Jailbreak was now a certified gold record in both England and Ireland, with sales of over 100,000 records.

The flight was uneventful, and we were soon landing at JFK. As we left the airport, our driver was somewhat amused by the fact that Philip never sat in the back of a car, he always rode upfront. As we sped along the freeway it felt like the beginning of something. We were still on a high from the success of the album at home, so who then would deny us the siren call that promised the same success for the album release in America?

We arrived outside the Hotel Mayflower on Central Park West where we would be staying for two nights before departing for our first show in the Midwest. I checked in, took the elevator up to the tenth floor, and as soon as I opened the door the phone was ringing. It was Sheryl Feuerstein, the national publicity director for Polygram. The PR machine had been set into motion. We had two days in New York and she had lined up many interviews for the band. There was no doubt this was now an important record for the company.

It was four o’clock in the morning and I was wide awake. I called the office in London and updated them: today was press, meet the Mercury Records staff, and then dinner at Angelo’s, an Italian restaurant on Mulberry Street. I knew I wouldn’t go back to sleep, so I showered, called the 24-hour room service and ordered a coffee. I read the free copy of the New York Times that the hotel provided and watched the news on ABC. This is life on the road in America. For the first week of the tour I would be waking up in the middle of the night, wondering which city I was in and where we were travelling to that day.

We flew out of La Guardia on the morning of April 17 to begin the tour. We were playing that night as a support to Rush at the Memorial Arena in Pekin, Illinois. The band had a great relationship with Rush, and they liked having us on the bill with them. What I recall from that first show was you could see that the audience were beginning to recognise the songs from Jailbreak, due to the airplay the record was getting. We were staying at the same hotel as Rush and met them later for a drink in the bar. It wasn’t a late one, as we had an early flight to Kansas City in the morning.

Sunday morning in Pekin was slow. It took forever to check out of the hotel, and the cab to take us to the airport was late, but we made the flight and in no time we were landing at Kansas City International. It was a day off, and I knew I wouldn’t see much of the band that day. That’s how it is on tour. You spend enough time together in cars and planes, once they got to their rooms I wouldn’t see them until the following morning.

I woke up on Monday to the sound of my phone ringing. It was Mike Bone calling from Chicago. He was calling to tell me that we were picking up airplay on all the AOR stations with the single. We need these, he said, before they will add the record at Top 40 radio, but he had no doubt that week-on-week we would pick up those stations. “It’s a hit,” he said. “I’ll see you when you get to Chicago.” I put down the phone, and thought about what he had just told me. From a conversation in a car a year ago, about how one song could define a band, we had a hit. Spread the word around.

When I told the band, there was excitement and disbelief – the song they were unsure of when they played it to me was about to be a hit in America. We played a show that night at Kansas’s Capri Theater, and the following night Chicago’s Riviera Theater. This was the first time we had been back to the city since we opened for Bob Seger and Bachman Turner Overdrive in early 1975 Afterwards the band went to pay homage to the blues in the many clubs on Rush Street, which were steeped in the music and history of Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, Little Water and Buddy Guy.

Somehow the appreciation that night of 12-bar blues turned into the band drinking in 12 bars. This was memorable mostly for a girl and a bottle of tequila. The band were drinking in one of those bars when she walked up to them and slammed down a couple of shot glasses and a bottle of tequila on to the bar top. “Drink, gentlemen,” she said. Immediately I could sense this would not end well – a pretty girl, a bottle of tequila, and a challenge to a group of musicians.

To this day I don’t know how Brian Robertson got back to the hotel. He had been missing for a day, and just as I was about to put out a missing persons alert he walked into the lobby of the hotel and asked for his room key. Before he disappeared into the elevator, he asked me what time we were leaving in the morning. I didn’t see him again until we were about to check out of the hotel.

It’s May 1 and we’re booked to do a couple of shows in the twin cities of Minnesota and St.Paul. We are playing third on the bill to Aerosmith and Slade in Minnesota, and special guest to Slade in St.Paul. After the second show, the band are presented with a stone jar of Tullamore Dew. I look at it, and realise it represents a gesture of giving the band ‘whiskey in the jar’. Wrong band, wrong time, but I thanked the giver for his enthusiasm and the whiskey.

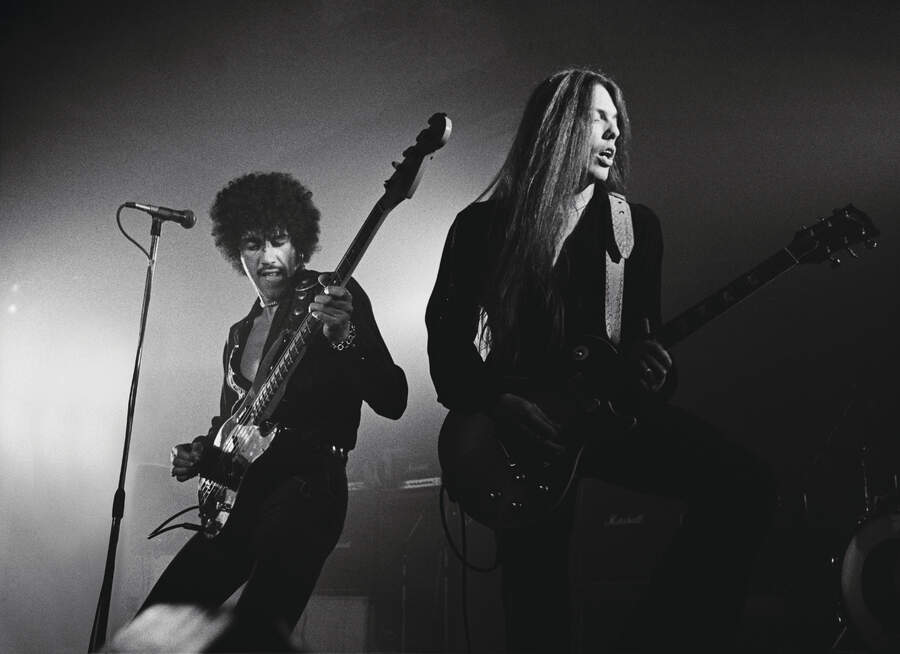

A day later we travelled to Allentown in Pennsylvania to play at the Roxy Theater for two nights. Although people are starting to talk about a song they are hearing on the radio, Lizzy haven’t actually played The Boys Are Back In Town much. It’s in the set, but it’s only a single in America, and nowhere else. But from the opening chords of the song, to Philip singing ‘Guess who just got back today…’ there was a connection with the audience that night that took it to another level. This was no Monday night at the Roxy Theater, this was Friday night down at Dino’s Bar And Grill. It was an extraordinary moment, and I remember sitting in the dressing room after the show talking to the band about the response the song got that night. Whatever happened now was all down to a song that was about to change the lives of a third-on-the-bill opening act in America.

After Allentown, we played a couple of club dates in New Jersey, and then headed to Philadelphia to play a show at the Tower Theater supporting The Tubes. It was on the drive to Philadelphia that we heard the single for the first time on American radio. I was driving a hired car along the I-95, listening to the radio, when the opening chords to The Boys Are Back In Town began. Phillip lent forward and turned the sound up. No matter how many times I was to hear that song being played on stage, hearing it on a car radio while driving on a freeway in America was a different experience altogether. As we reach the outskirts of the city, I wonder if they will be ‘rocking on Bandstand in Philadelphia PA, where the cats all want to dance with sweet little sixteen’.

I pull into the parking lot of the hotel and check in at reception. There are messages waiting for me: call Bone, Feuerstein, the office in London, and Nigel Grainge. The single and the album have charted on Billboard and Cashbox, we are selling records. I tell the band I will see them later at the venue, I have calls to make.

My days and nights are now about arranging times when the band can be interviewed, on a phone, at a radio station, with a journalist, before a show, after a show. Everyone is important, no one is unimportant, everyone loves the album, the single, the band… The phone in my hotel room is ringing off the hook. Finally I just have time for a coffee before I take a cab to the Tower Theater. Larry Magid is the promoter and he has put a great bill together; The Tubes and Thin Lizzy show is completely sold out.

There are some people to meet afterwards, and then we head back to the hotel. It’s an early flight to Cleveland in the morning. Mike Bone informs me that WMMS in Cleveland picked up the single early, and this is why the show at the Agora Ballroom is sold out. The important thing is not only are we getting played on radio, but we are playing all the right venues for a band at our level. It is encouraging that the promoters are booking us. After all, they are putting money behind the belief that we will make it in America.

Hank LoConti runs the Agora Ballroom, and as the band sound-check he tells me the phone has been ringing all day for returns. WMMS is a co-presenter for tonight and they have been playing the album from its week of release. Even before the doors open there is a queue forming. Cleveland is going to give the band a great ‘Rock Capital’ welcome.

Watching from the side of the stage that night, I began to notice how easily the band were adapting to playing to American audiences who were seeing them live for the first time. Cleveland did indeed give us a ‘Rock Capital’ welcome – which somehow seemed to last until the early hours of the morning.

At the airport the next day, we are waiting in departures to fly to Racine in Wisconsin and the band are grateful for the plentiful hot coffee.

The next couple of days we are playing shows in the Midwest including one in Kansas City with the Charlie Daniels Band. We are getting ever closer to the West Coast, where we are scheduled to play some shows with Journey, including a date in Los Angeles.

When you’re on tour, it feels like you are on a moving train that never stops at a station long enough for you to get off. We opened for Journey in Portland, Oregon and they stand at the side of the stage watching the band. They are fans, and they are pleased we are playing these dates with them. The next day we flew to LA, a car picked us up at the airport. and by the time we hit Sunset Boulevard it felt like we were driving through a film lot.

We checked in at the hotel and I took the elevator up to my room on the seventh floor. It was now the beginning of summer, and I stepped onto my balcony to look down on Sunset Boulevard. There was a knock on the door. Philip walked into the room and joined me out on the balcony. He didn’t have to say a word as we looked down on Sunset, he was remembering that I had once said to him: “You are nothing till you can make it in this town.” Now you couldn’t turn the radio on in this town without hearing Thin Lizzy.

He asked what I was doing, and I said I was going to take a shower and then walk up to Tower Records. Later I was going to eat at Carlos & Charlie’s across from the hotel, and he said okay, he would meet me there as he had some interviews to do. I wasn’t sure what the rest of the band were doing, but I knew that at some point we would all meet up at the Rainbow Bar & Grill.

When we arrived there we were given a booth, and for the whole night the band were greeted by people in the club as if they were being anointed as the Next Big Thing. Why not? They were Thin Lizzy, and they had a hit record, and that would get you an invitation to everywhere you wanted to go in LA. Around two o’clock I decided to go back to the hotel. Someone asked if I needed a ride. I said no, I wanted to walk back along the strip. He gave me a look that said: “No one walks in LA.”

The following morning I woke up to the incessant ringing of the phone in my room. It was a show day, people were requesting interviews, asking to be put on the band’s guest list. The BBC called. The single is a hit in Britain and they needed to film a clip of the band performing the song for Top Of The Pops. A studio was being booked and a film crew was flying out to film the band lip-synching to the song. I sat on the balcony of my room for a moment, just to feel the warmth of the sun on my face… One song, that’s all it took. Suddenly the phone rang again. I let it go to message and went to have breakfast instead.

Later that day I sit in the auditorium of the Santa Monica Civic Center and watch the band sound-check. The show is sold out for Journey, but all the attention is for Thin Lizzy. I talk with Susanella Rogers, head of West Coast PR for Mercury, to discuss the aftershow party she has organised at the Old Venice Noodle Company in Venice Beach. She shows me the invite list – it’s stacked. There are press, radio and record company people among the names, all of whom have responded in the affirmative. After the show we head over to the party. The room is full and everyone wants to talk to the band. The party breaks up around 2am and I get a cab back to the hotel. We’re filming tomorrow and the band has an early call.

The following evening, over dinner on Malibu Pier, I discussed the progress of the album with some of the guys from Mercury. I told them I was being inundated with offers from promoters to extend the US tour. We had agreed to be special guests on the upcoming tour with Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow, which would take us through the end of June. The longer we stayed in America, they said, the more opportunities there’d be for us to promote the record.

It was hard to sit there that night in a restaurant overlooking the Pacific Ocean, and not think about the speed at which all of this was happening. The band had gone to The Rainbow. It was our last night in LA. Next stop Chicago, then on to Texas where they are scheduled to play three shows.

We flew into Dallas from Chicago – we are in cowboy country now. And from the moment the band stepped on the stage of the Electric Ballroom that night, they had the audience in the palm of their hand as Philip sang the opening lines to Cowboy Song.

The next day we drive to Austin to play at the World Armadillo HQ. It’s a couple of hours in the car, and I have no idea why the venue has such a name. But on arrival the promoter, Eddie Wilson, begins to tell me the history of the venue. It was originally an old National Guard Armoury, which had inspired a local artist to design a poster for the first ever show there, using an image of an Armadillo. As I sit in his office, I look around at the framed posters on his wall – Ray Charles, Janis Joplin, Van Morrison, Linda Ronstadt… Now you could add Thin Lizzy to that roster. It’s not by chance that you become a great live act, it’s when you play venues like the World Armadillo HQ that you begin to hone your performance to the level of those artists.

After a late breakfast we check out of the hotel for the short drive to San Antonio. We are playing a show at the Municipal Auditorium with Rush that night, but we all want to see the Alamo before we go to the venue. Davy Crockett, king of the wild frontier, made his last stand here.

The show that night is sold out, and afterwards we meet up with Rush at the hotel. They are pleased that we are doing so well with the record, and we sit in the bar talking about life on the road and about their plans to come to England at some point. Philip doesn’t stay long in the bar, he says he is feeling tired and we are flying to Nebraska the following day.

June 10, 1976. We have been added to a show with Nazareth and Slade. It promises to be the kind of night where you can’t wait to meet up with them and catch up with all the news from back home. But it is a muted performance that night. Philip thinks he has a bug. I promise to get him to a doctor when we get to Columbus, where we are due to begin the tour with Ritchie Blackmore, but he doesn’t want to make a fuss. There is definitely something wrong. Philip is telling me he can shake it off, but I’ve never known him to be sick like this.

We fly to Columbus that morning and I have called ahead to get a doctor to come to the hotel. Again, he tells me it’s just a bug, but he looks jaundiced and that suggests something far more serious to me. Upon landing we head straight for the hotel, where the doctor is waiting for us. He takes one look at Philip and tells me this is serious and arranges for him to be admitted to a hospital in the city for tests. Privately, he tells me that he suspects Philip has hepatitis, which a blood test will confirm.

We go to the hospital and Philip undergoes some tests. An hour later it is confirmed that he does indeed have hepatitis. The doctor wants to admit him, I don’t. While waiting for the results, I have been on a payphone, calling the travel agent to book Philip on a flight to Manchester connecting through London that night. We get a cab back to the hotel so that I can let the band know what is happening.

The first person we see is Scott. He takes the news really badly. The tour is over and he has no idea what this means in the long term. Everyone comes to my room and I explain the situation, while Philip is on his way to the airport. I have to call the agent, the record company and the office to give them the news. The plan is to get everyone back to England via New York, where I have arranged for the band and crew to get shots to prevent any of us getting hepatitis, so after my calls we’ll get a late flight to New York. I go down to the Village for dinner and think about what this will cost us. All of the plans to extend the tour to promote the album have come to nothing.

Already Mercury are talking about the next record, but I can only think about this one. This is not how it was supposed to be. We have a gold album in America, every promoter wants to book the band, but we are leaving tomorrow. I walk back to the hotel, as the traffic is so bad it makes no sense to sit in a cab going nowhere.

The following morning I wake to the sound of my phone ringing. The story has broken back home and I am being asked for quotes as to the exact nature as to why the tour was cancelled. It runs in all the papers and on radio, and when it does I am on an overnight flight back to London, so there is no further comment from me.

As I wait for my bags in the arrivals hall at Heathrow, the band and crew are asking me what happens next. I am not sure what happens next, but I am going to go home, and then to the office to talk with Chris Morrison about what’s next. I tell them to take a couple of days off, and I will call everyone to let them know the update on Philip once I have some news to share.

As I leave the airport it’s a warm June day, unlike the stifling heat of New York. I get a cab into London. The cab driver has his radio on, and suddenly I hear the words: ‘Guess who just got back today…’ Oh, the irony.

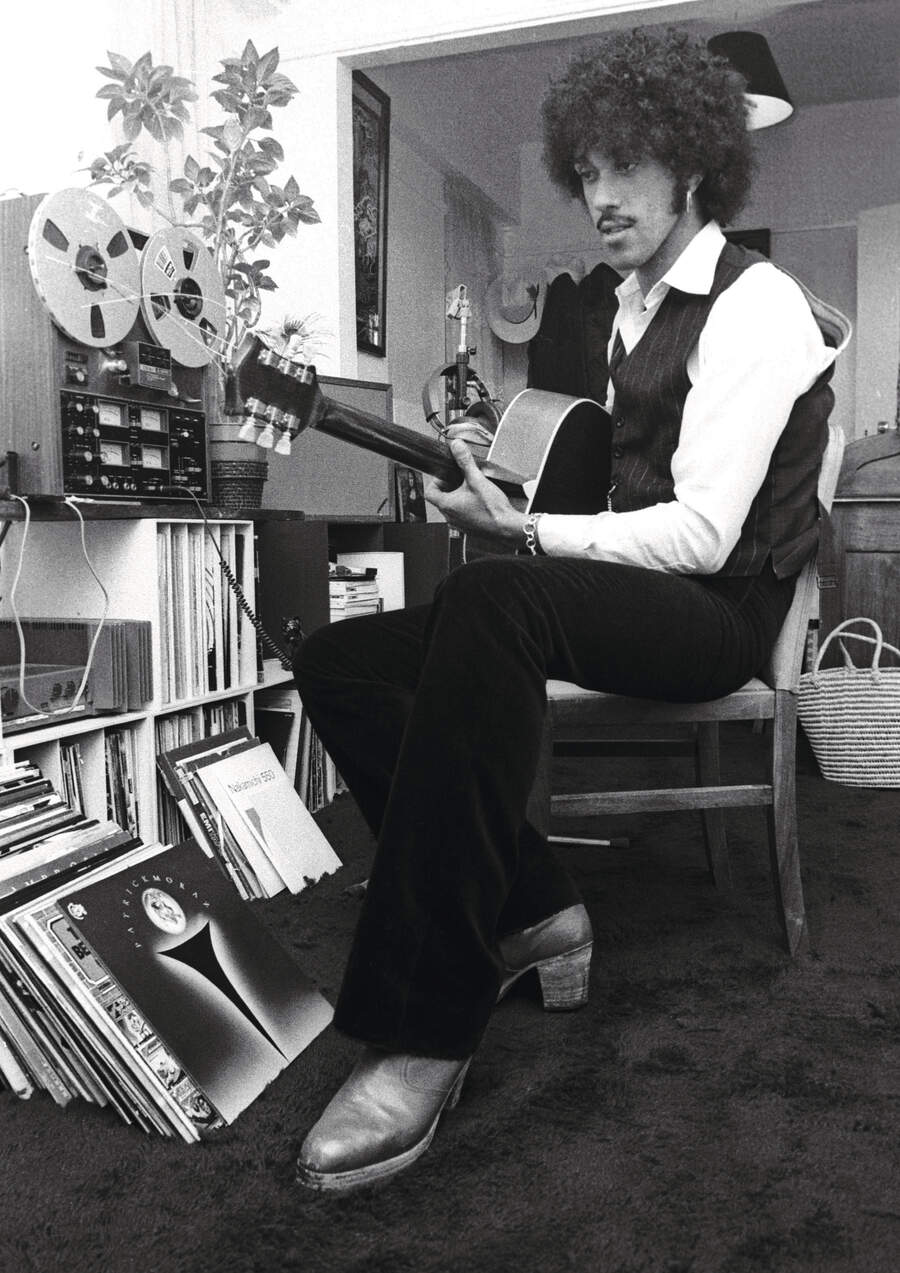

A couple of days later I take the train up to Manchester to spend a day with Philip, who has been in hospital ever since he got back from the US. He has been told that rest and antiviral drugs will make sure that for the immediate future the virus will clear up. While he has been in hospital he has kept himself occupied with an acoustic guitar and a notebook to write down some ideas for songs. He is in a side room for privacy, and as I sit with him he tells me how overwhelmed he has been, with so many people calling the hospital and writing cards to him. It was for this reason, he says, that we should do a show in London to thank everyone.

While he is still upset about having to cancel the American tour, he argues that the quicker Lizzy become visible again it will stop people speculating about the band’s future. I use the phone in his room to call the office to find out the availability for a date at Hammersmith Odeon. Before I leave Manchester that day, we have a show in London confirmed for July 11, and Philip is talking about recording a new album.

On the day of the show, London is in the middle of a heatwave, the show is sold out, everyone wants to see Thin Lizzy. As they walked onto the stage that night, the reception was enough for the band to forget the disappointment of having to cancel the North American shows with Ritchie Blackmore. In the wings that night, looking on and waiting to make an entrance, was Johnny the Fox, tuned in and listening to the band…

Thin Lizzy 1976 is now via UMR . Chris O’Donnell’s book ‘The American Dream Of Thin Lizzy’ will be published in 2025.