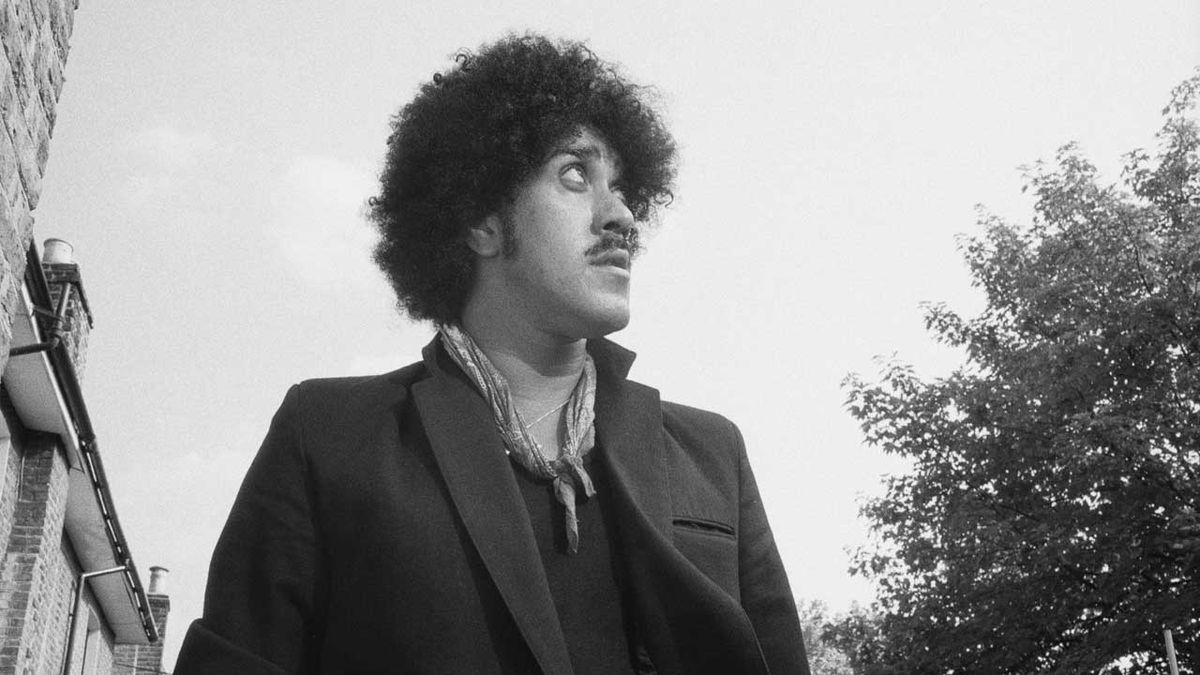

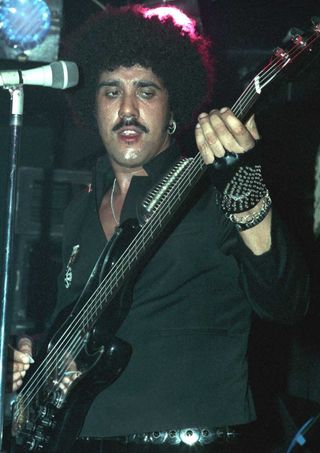

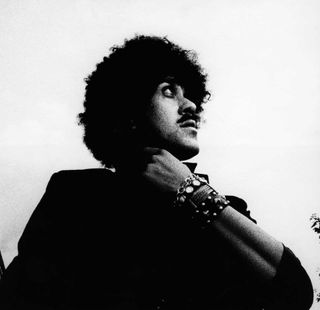

When the call came that Phil Lynott had died, Thin Lizzy fans everywhere went into shock, devastated at the news. ‘Phil Lynott’ and ‘dead’ were words that one could not possibly imagine being put together. The writing had been on the wall for some years, but no-one – not fans, friends, band, management, record companies – could believe that he had actually succumbed to the inevitable.

It was common knowledge that Phil’s post-Thin Lizzy career had gone off the rails and that his dependence on drugs – loads of them – was not helping. His band Grand Slam had ground to a stuttering halt before breaking up, his marriage was in trouble and his personal life was being openly examined, many times in the courts. This all contributed to putting him in a very bad place, although news of a solo deal brought some hope.

Phil, though, was not one to help himself.

The rot had set in some time before, when partying took almost as much precedence as recording during the Black Rose sessions in Paris, eventually forcing Gary Moore to jump ship during an American tour. The warning signs were not heeded. The much straighter, but experienced, Snowy White started by taking Lynott and Scott Gorham’s drug-taking in his stride before push came to shove during preparations for a new studio album in Dublin.

On a work level, White was despairing of working with Lynott: “I didn’t know him as a person at all. After the first six or seven months, it got to the stage where I couldn’t be bothered any more because I just couldn’t get through. He never opened up. I could never talk to him as a friend. He was always trying to prove something. We all know how difficult it was to deal with Phil. One minute he’d say one thing, and the next day he’d prefer not to remember it. You couldn’t win with him. We’d make plans to do this that and the other, and then it would all be changed.

“I found myself just drifting further and further away from him and the band. It was my fault as well because I wasn’t a strong character in that set-up.

“I would stay in the studio as long as I could stay awake. I used to be up about eight in the morning, get to the studio at one and Phil and Scott might turn up at seven and work all night because they had things to keep them awake. Come midnight I was starting to sleep.”

During Snowy’s era, Phil’s attention was spread between recording both band and solo albums, and that irked White too: “I didn’t know what I was playing on. We didn’t know what was going where, which pissed me off a bit because if I played on Phil’s solo stuff, I would have wanted session fees… It’s my business and job.”

The frustration was palpable as he talked about the relationship not long after Phil died: “I don’t know enough about drugs,” he said. “I didn’t know what was going on… Obviously there were a lot of drugs around, but I don’t do them so I couldn’t tell if moods were drug induced or natural. That made me an outsider, I suppose. If you join a band like that, either you jump in and do everything or you stay outside and be the odd one out, and I have always been very happy being the odd one out in situations like that. I would never get pissed or take drugs just to be one of the boys. I didn’t feel involved when we went out.

“But I was still hoping it was going to change. There were often times when things looked as if they were going to change – in some of Phil’s more sensible moments. Where he would see that this could crumble around his ears – partly because of how difficult he was to be with – which it did.

“By the end, I was keeping well out of it. On tour by then, I used to come back to the hotel, have something to eat, go to bed, then get up the next morning and have a look around whatever town we were staying in. I’d pass the boys coming in from a night out. They’d sleep all day and we’d meet at the gig. We didn’t talk much, there was nothing to talk about.”

White stuck at it for a while – Chinatown and Renegade were both solid albums in the Lizzy canon, and while White may not have shaken his booty on stage, he was a complete blues rock player in the studio, an ideal foil for Gorham. But then it all became too much as he prepared in Dublin for his third album with Thin Lizzy.

Even before getting on the plane for Ireland, White was already doubting his future and had an inkling that maybe Phil and Scott were thinking the same. He also let manager Chris Morrison know that he was going there to work, not to wait on his colleagues to shake off the previous night’s drink/drug hangover. Morrison promised to talk to Lynott and Gorham.

For two days, all was fine, then what had become the usual kicked back in. Phil couldn’t make it because he was “sick”, Gorham turned up late. While the rest of the band retired to the pub, White worked on some material that Phil promptly wiped the next day. Back in London, White considered his options and decided enough was enough.

“I was lying in my bed and I thought, ‘I am not going into that studio to sit around until somebody out of their brains wanders in at seven o’clock at night and wants to work all night’.” So he didn’t.

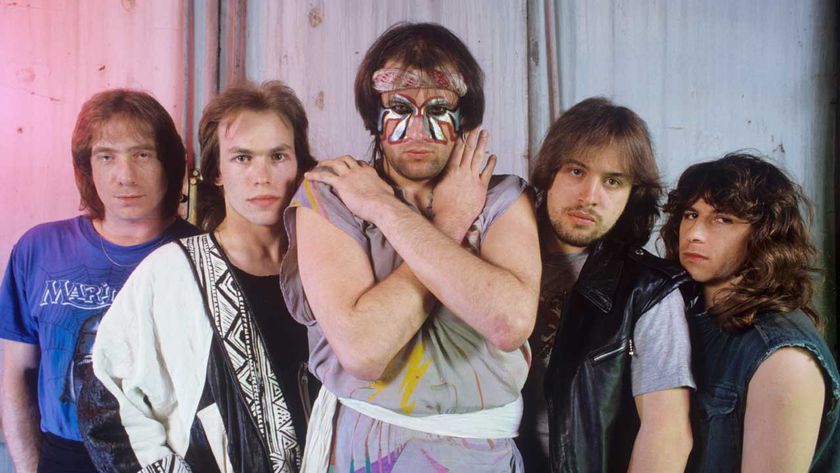

John Sykes would have seen the same things happen when he joined for the Thunder And Lightning album and tour, but was young and impressionable enough to let it wash over him. But by then even Scott Gorham had had enough.

“John came into this band thinking, ‘This is going to be great, I’m a star now’ but, unbeknownst to him, we knew that that album and one more tour was it,” Gorham remembers. “So I felt sort of sorry for him. It was Phil’s idea not to tell him. He was afraid that if John was told he would quit the band. Kind of shitty, but there you go. In the long run, it didn’t really hurt John at all. It helped his career.”

For all of the plaudits poured on Thunder And Lightning at the time of its release and since, the main men in Lizzy weren’t that enamoured with the album. “We weren’t pleased with the songs and there would be arguments,” says Gorham. “The drugs were flying. Always… Some people wouldn’t work until they were stoned – me for one, Phil for the other. People were nodding out on the console. This metal sound full blast coming out of the monitors and you’re nodding off. Taking drugs drains your whole being. You’d rather be doing drugs than recording. And I had had enough of it.”

A lengthy (farewell) tour to support the album and that was that. Life was an apt title for the live album that followed, for the disbandment of his beloved Thin Lizzy would tear its founder apart, especially as the decision was pretty much forced on him by the ever dependable mate and co-founder Brian Downey, and principally by his partying buddy and fellow band frontman Gorham. Lynott would spend the rest of his life trying to resurrect Lizzy, if not in name then in sound. Tragically, it turned out that his efforts continued to be narcotic-assisted.

To those around him, it was obvious that Phil was not in good shape. I had witnessed it at close quarters. Once I had called him at his home in Kew and he fell asleep on the phone. Where was the man who when I called him at his West Hampstead flat in the early days couldn’t speak because he was “busy”, a euphemism for engaging in intimate female company? Another time, I experienced Phil’s deteriorating state personally when I was asked by his record company to do an electronic press kit (ie a recording) which couldn’t be used because his voice was shot due to drugs. Of course, like everyone else, I thought Phil was invincible and would come through this.

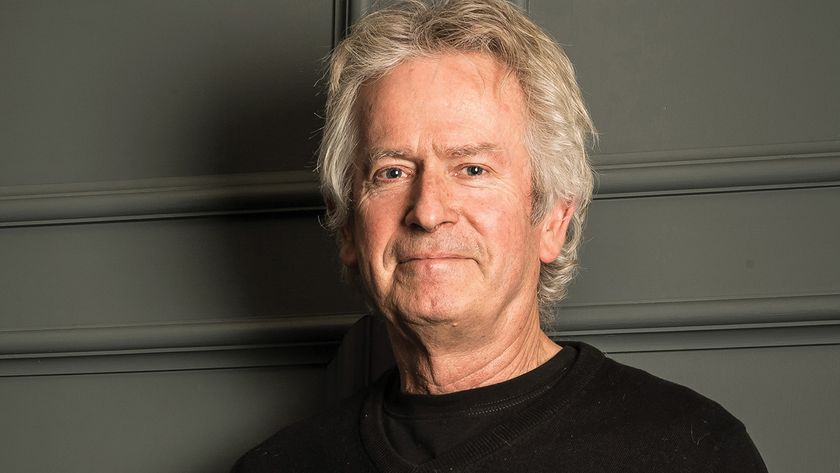

While Scott Gorham was getting used to the idea of giving up heroin and taking a break from all things associated with his use (for example, not hanging out with other users), Phil barely paused for thought after the final Lizzy gig at Nuremburg’s Monsters Of Rock in September, 1984.

“I came to the conclusion that I gotta stop taking this shit,” says Gorham. “It took me over a year after leaving the band to get it through my thick-ass fucking skull that this shit was going to kill me or ruin my career, which was on the way anyway. I had been to the Priory two or three times and failed miserably, tried it on my own and failed miserably tons of times.”

Eventually, his wife Christine found him treatment in California with Dr Meg Patterson, who had previously helped ween Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page off smack with her NeuroElectric Therapy treatment. She placed two electrodes behind the patient’s ears and connected them to a Sony Walkman-like black box that is worn continually night and day. The box sends out a weak electric current which, according to Patterson, stimulates production of several neurochemicals including pain-reducing endorphins.

The release of endorphins, normally interrupted by consumption of heroin and cocaine, eliminates the classic traumatic symptoms of withdrawal: anxiety, runny nose, stomach cramps. It’s a short-term treatment which requires immense will from the patient to then stay away from the drugs. Gorham was determined to do it.

“The treatment only takes ten days,” says Gorham, “but the mental part takes a couple of years to get over the addiction. I went to Los Angeles and stayed over there for about six months straightening out my head, staying out of the way, just trying to play a little guitar and do a little recording. I was determined not to play any Thin Lizzy at all… and I didn’t. I wanted to try something different.”

Meanwhile, Lynott was already plotting the next phase of his career with a three-week tour of folk parks in Scandinavia. All he needed was a band! Brian Downey and John Sykes were in, as was Magnum keyboard player Mark Stanway, who had been introduced to Phil by Skyes after a gig on the Thunder & Lightning tour, hooking up again at the final Reading festival appearance.

“I ended up going back to stay a couple of nights at his house in Kew with him and John and I ended up staying a couple of nights and that basically became two years,” says Stanway.

The second guitarist on the tour was Doish Nagel, from Dublin blues-rock band, the Bogey Boys. It all seemed to have echoes of Thin Lizzy – two guitars and all. After one rehearsal, Lynott’s solo tour of Sweden took flight, the set consisting mostly of solo album material, with four Lizzy tracks. “I don’t think he would have got away with not playing them,” Stanway laughs. One of the Lizzy songs played was Sarah, which had never been played live by the band.

As the tour progressed, Lynott was seeing the potential for a new band. Stanway: “After about seven or eight gigs, Phil was so happy with the way it went that he said, ‘We gotta keep this together’.”

Ensconced back in the UK, rehearsals and the writing of new material started with a band that was now called Grand Slam. Then Lynott’s confidence was shaken again twice in quick succession. First, John Sykes was offered a gig in Whitesnake by David Coverdale, who was impressed by him when Lizzy and Whitesnake played together at that final German tour gig. “John saw an opportunity,” Stanway added. And probably an escape from the madness that was becoming life with Phil Lynott.

Then Brian Downey announced that he was calling it a day. He’d grown tired of the shenanigans in Lizzy’s latter days, was said to have issues in his personal life and could see no improvement as a member of Grand Slam. One quote had him saying that he wasn’t “interested in playing in a second-rate Thin Lizzy”.

Mark Stanway: “I think Phil was still on a bit of a low [from] when Thin Lizzy had finished. Close to the time we did the Swedish tour, he’d been to Africa for a holiday and, I know this sounds weird, but he came back with a great tan! He looked so healthy. He was the heaviest I’d seen him but it was a healthy heavy if you know what I mean. He looked full of life. In those initial times he was in a good state but he was easily depressed. The man wanted to get out and perform.”

Replacements were sought and finally found for Sykes and Downey. Irish drummer Robbie Brennan was known to Lynott, and Stanway reminded him of a young guitarist called Laurence Archer, who had been an erstwhile member of the Brian Robertson-Jimmy Bain band, Wild Horses.

Phil always had an eye for good young and good-looking guitarists, and Archer ticked all the boxes. Archer had met him a few years previously through the Wild Horses connection when Phil jammed with the band at the Marquee Club. He then invited the guitarist to a Lizzy recording session in Maida Vale where Archer got the impression that he was being auditioned, though Snowy White was still in the band. When Snowy left Lizzy, says Archer, he was “sort of approached about doing the Lizzy gig but at the time I thought Wild Horses were going to be the biggest thing since sliced bread so I stayed with that. That’s when John got the gig.”

Archer adds: “He was still an idol to me. I grew up with him and Thin Lizzy. When I was 17 I said to my father, ‘That’s who I want to play with’.”

When Sykes moved on to Whitesnake, Archer was called upon again and filled in on the plans for Grand Slam in the rock’n’roll surroundings of Stringfellows in Leicester Square, then a favoured hang-out for a certain kind of rock star. “Basically, Phil said that he wanted to do something new with two guitarists, fresh with new blood, write new songs, sell it as a whole new band and not as a solo project. He wanted a band but he wanted it to be new, fresh and nothing to do with Lizzy,” says Archer.

The new band recorded at Phil’s home studio in Kew before heading for Dublin and rehearsals in the community centre in Howth, a suburb of Dublin near Lynott’s home there. New material written by Lynott, Archer and Stanway was emerging, including Military Man and Sisters Of Mercy, before Lynott showed the band how things were done in Ireland when it came to playing live – the showband circuit that was often used by Lizzy to sharpen up before tours and replenish the bank account! “We must have played in every county in Ireland,” Stanway laughs.

Back in London, Grand Slam’s management of Chris Morrison and tour manager John Salter set about finding a record deal for their new charges. Though Morrison was the figurehead, it was Salter who looked after the day-to- day business of Phil and Grand Slam: “Chris had his empire [Nineteen Management with Simon Fuller] and he didn’t have time and he and Phil didn’t see eye to eye,” says Salter. “So I came back to manage Grand Slam.”

The original aim had been to go to America, find a house and work from there but… “Phil kept getting busted so I couldn’t get visas!”

What could be the problem though – a new band coming off the back of a legendary band with a proven chart past? But it wasn’t to be so easy, and the reasons soon became apparent.

Stanway: “We went into the studio to record these tracks to a decent level and quality and they hawked them about. Polydor had them and Phonogram and EMI – all the majors were given the opportunity, and whilst negotiations did go on, nothing was finalised and nobody actually picked up or came up with a sufficiently good deal for us to sign.

“I think it was because of Phil’s reputation, because he was a bit of a wild man. And of course he did have bad days on the trot. There were a bunch of hangers-on that used to come round to the house and give him whatever he wanted.”

Laurence Archer remembered coming back from the Irish rehearsals and dropping Phil off in Kew. While Archer headed home to Teddington, Phil and his trusty personal roadie Big Charlie (McLennan) freshened up and went to a party in the West End. Unfortunately, the drug squad swooped and while Phil wasn’t charged, the press got word that he was there.

“After that, we’d get followed by police on tour which became a bit of a thing,” Archer remembers with a tinge of sadness. “There was an entourage and reputation that went with Phil. But the band was playing really well. The gigs were really good, everything was going very well. We loved it. Phil was like a father to me at times, and it almost became like a reverse role as we went on, with me looking after him. At the time I was very, very straight. Into fitness, biking and all that. Didn’t touch drugs, didn’t smoke, didn’t drink very much.

“I found it all a bit overwhelming. I was only 20 years-old and suddenly being put into this position where I’m not only playing with somebody who is an idol as such but also being part of his personal life and family life, living in his house, spending 24 hours a day writing and working. But I loved it, it was a massive experience for me.”

Stanway was aware of the heavy drug use, and particularly Lynott’s growing dependence on heroin. “Heroin was a bit of a swear word as far as I was concerned. Don’t get me wrong, I’m no angel but that stuff is just a one-way ticket. But he never did it in front of me because I would say I would tell his mother if he did. That was the one big thing that would get to him.

"She said to me, ‘Mark, you tell me if you ever see him do it’. ‘The gear’ as she called it. So he wouldn’t let me see him do it. But Phil was fantastic at disguising his use, though there were some give-aways, like throwing up before he went on stage.”

Archer would notice Lynott’s mood swings. “He blew a bit hot and cold, to be honest. He’d be difficult, you know. Some days he’d be easy and some days he’d be difficult and when he was he would come and apologise afterwards.”

Mood swings related to drugs? “I would say so, yes! I mean, there were occasions where Phil sat down with me and told me that he really wanted to knock it on the head, doing drugs and stuff. He was trying very hard to clean up his act for some periods of time and management tried to keep anybody with drug connections away from him and the tour entourage but it was very difficult.”

And he wasn’t helping himself obviously.

“He wasn’t helping himself at all. It was on a plate for him. People would be turning up at the door and there were various people in the entourage that were still doing all that, so it was quite difficult for him to get out of that routine.”

While Phil tried to balance a life between music and drugs, his management was struggling to find a deal for Grand Slam.

“Phil was really down at the end of at the end of Thin Lizzy, it seemed like the end of everything for him,” says John Salter. “Thin Lizzy was just his whole life. He lived it 150 per cent. For someone to turn round and say, ‘This is your last show’, he did find it very difficult. And when John [Sykes] left and took the offer from Whitesnake, that brought him down too. So when a deal wasn’t immediately forthcoming for his next project, he wasn’t happy.”

Salter had taken over the mantle of former manager Chris O’Donnell in running the day-today affairs of both the band and Lynott. “When he asked me to come back, he was pushing me all the time. He’d had his lay off and wanted to work again.

“But we were turned down by just about every record company there was… I think his reputation preceded him. CBS knocked them back. Said it was a bit old, weren’t convinced. We were looking for a proper albums deal – £100k plus. There was a long period without a deal, a year and a half. He realised there was something wrong, and he didn’t think it was the material. He started blaming the band.”

But Grand Slam continued to rehearse, record and gig, as Laurence Archer put it: “Musically, the band had some potential. We did a load of tracks, some that were never recorded to their potential, some that we played live but never recorded, some we recorded and never played live. I would say there are probably 48 track mixes around somewhere that we got close to mastering.”

“We remained optimistic because the band got better and better,” says Stanway. “And the audiences were loving what we were doing and we were getting booked back and the gigs were getting bigger. What started off as Marquee-sized gigs ended up as theatre gigs. Maybe the record companies may have thought, ‘This isn’t Thin Lizzy – and that’s what we want’. To me it wasn’t that different – there may have been a bit more keyboards. Record companies at that time didn’t have a clue what to do, but I’m sure we would have sold records. We sold lots of t-shirts!”

It was becoming more obvious to all concerned that Grand Slam was not going to be a creative or financially viable entity. Gigging was bringing in some money, but management had put in substantial sums that they were rapidly realising that they, and in particular Morrison, would not see a return on.

So Grand Slam went out with a fizzle rather than a bang. Mark Stanway’s options with Magnum were opening again. “Magnum asked me to do a tour because a new album was coming out on FM/Revolver,” he explains. “And then because of that we were offered a major deal with Polydor. I had to make a decision at that point. Phil let me go on tour with Magnum because we weren’t doing anything as Grand Slam.

"That was around about spring of ’84 and that summer we [Magnum] did Donington. I had to make a decision and Grand Slam had nothing in the pipeline, nothing pending… so I said, ‘I’m going to stick with this because I’ve got an opportunity’. Phil tried to talk me out of it but understood that I had three kids and a family to support. He accepted it…

“I don’t want it to sound like I was deserting him. You have to make sensible decisions in your life. I think I would have gone broke very quickly if I had sat around waiting for him to get his act together or waiting for a record company to pick us up.”

And, of course, the word was filtering through to Phil that he might stand a better chance as a solo artist. Laurence Archer, however, stayed the course as his creative partner.

“We thought there was something in the background as to why he couldn’t get a deal,” Salter remembered. “We said that his reputation was one of the problems. But he said he didn’t have a problem and for a long time I was convinced.

However, a series of drug busts for Lynott weren’t helping his cause, and he was worried that a drug conviction would harm entry into the USA.

There was one bust at the Kew house where the police arrived at seven o’clock in the morning claiming to be from the gas board. Lynott was charged with being in possession of a cannabis plant. Salter says that one of the road crew gave him a cannabis plant as a joke. They also found some cocaine – “Not very much!”

On another occasion, roadie Big Charlie took the rap. Stopped in a cab late at night small amounts of cocaine and heroin were found in Phil’s jacket. Charlie claimed that he had borrowed the jacket and the stash was his. Phil got off with a fine but it was a close thing: “Prior to the hearing the barrister had told him you’d better be prepared to go away for a month,” Salter recalls. “When we got to the court, she said, ‘This could be six months, you’re in it this time.’ He was terrified when he stood in that box. He pleaded guilty and he came out of that court and said, ‘That’s it – I’m going clean’.”

The judge decided to give him one more chance. “If you come before me again, you are going away,” he said. In his favour was his charity work, the fact he had a career going for him. “He gave him another chance but put it on the record if he came to court again, next time he would go down,” Salter recalled.

Shortly afterwards in Ireland, Phil was charged with being in possession of cannabis, heroin and methadone. The charges were dropped – he was adamant that they had found scrapings, at least that’s what he told Salter, who was becoming increasingly frustrated at pulling his charge out of the shit while trying to get his career on track.

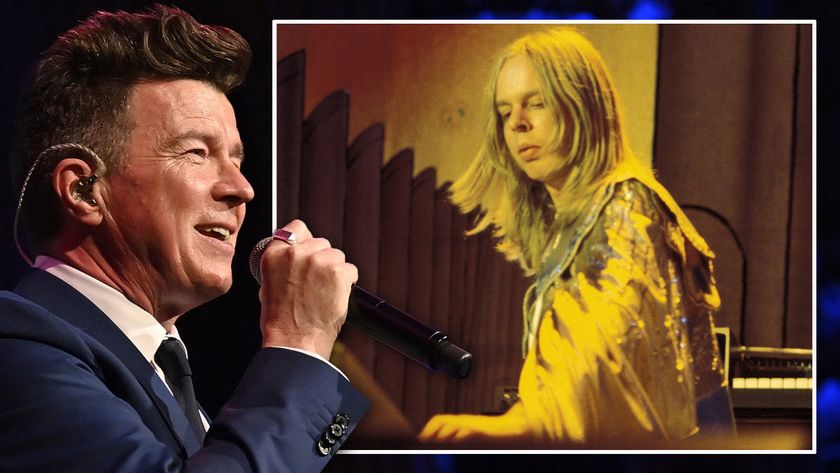

Part of Salter and Morrison’s plan was to give Lynott’s career a lift by using influential friends, in the shape of Huey Lewis. Lewis was an old friend from way back on the Johnny The Fox tour in 1976 when his band Clover supported Lizzy. An American R&B group paired with a hard rock band in front of some of the most die hard fans known to man – Clover never stood a chance. But Huey, who went on to find outstanding success of his own in the States alongside his own band, the News, understood this.

“We got booed off some of the best theatres in Britain!” he laughs today. But he got on particularly well with Lizzy, joining them on stage for Baby Drives Me Crazy (which appeared on the Live And Dangerous album): “Philip would watch every show and he was so encouraging and would offer advice. And he was the one that encouraged me and said, ‘You should sing more songs’. We developed a wonderful friendship. I mean, he dressed me out of his closet. He gave me his old stage clothes.”

Lewis also worked on material for the solo albums, Solo In Soho and The Philip Lynott Album. “He was wonderful, man. I think about him often. Thin Lizzy were the best hard rock band I’ve ever seen.”

So when the call came to help Lynott out by writing, recording and producing – at a time when Huey Lewis And The News were big news indeed, he had no hesitation in saying “come across”.

Back in England, Lynott and Archer were working out the songs that they planned to record, including an Archer song called Can’t Get Away and a Huey Lewis track, Still Alive, plus some Grand Slam tracks.

As Lynott, Archer and Salter got their bags together to travel to San Francisco to start recording, another problem surfaced – Phil couldn’t find his passport. It particularly irked Salter: “He lost his passport five times in three years, so the Irish Embassy turned round and said, ‘No more’. This actually happened as we were about to go and work with Huey.”

Archer set off on his own to start recording backing tracks with Huey and his band, who had a designated slot in their busy schedule. “Plans were thwarted right from the start,” recalls an exasperated Archer.

Salter wasn’t giving up, though: “Eventually, the Irish Embassy issued a passport for a month. Then we had to go and get a new visa, at the American Embassy. I was waiting for him, going slightly insane, when somebody at the US embassy recognised him and said, ‘Hey, this guy has drug convictions…’ and no declaration had been made about these. That was it – no visa. Three or four days in, Huey Lewis And The News are waiting. Huey understood Phil so we started work anyway. The News came in and did the backings with Laurence Archer. Then Phil finds his old passport, with a visa in it, so we got him down to the airport and got him in. He was eight days late getting there.

“When the embassy found out what we had done, they went crazy and withdrew the passports again. After that they agreed to give him a monthly passport as long as it was in my possession. Every month, I had to go and renew it, and after six months, they gave in. Then we had to get a visa lawyer, and very expensively we got one.

“At one stage, while we were waiting for the passport, he got arrested again! As usual, Phil was pushing his luck.”

Lewis remembers the sessions: “We almost had ’em done. I had arranged them so that he was singing back up in his range. For about three or four years, he hadn’t sung in The Boys Are Back In Town or Jailbreak range. He was singing way down low on his solo stuff. We cut the tracks, and then we did a vocal on Still Alive and Can’t Get Away – Archer’s song. They were great. He struggled with the vocals because he couldn’t get up there but it was almost perfect. It wasn’t easy but I worked him pretty hard. We almost got it done when he had to leave.”

As Lewis recalls it, Lynott was in good shape: “He was okay. He was clean. He was good. I insisted on that. He needed to be clean or I wasn’t going to work with him.”

That’s not how Archer remembers Phil in the States: “Even in the in the small amount of time I had been in the States and not seen Phil, he was in a pretty bad state when he arrived. He wasn’t very well – smoking, wheezing, coughing and had put on a lot of weight.”

Unfortunately, not as much work was finished in San Francisco as hoped for – unsurprising in the circumstances. Some backing tracks were recorded with no vocals, but generally, everyone was happy with the two tracks practically mastered – Still Alive and Can’t Get Away, and Salter had renewed confidence that he could seal a deal on those. Unfortunately, unbeknownst to Archer, he would not be part of it. But by then he too was tiring of Phil’s drug-addled ways.

Archer spoke with Morrison. “I knew there was potential in my writing and we came back and I said to Chris, ‘This is all very well but I don’t know where it’s going. I want an outlet to do some writing and start something else; Phil is not in a good way and we don’t know where it’s going to go’. From what I understand since it was not discussed with me, to my mind there was a bit of skulduggery – basically what happened, I believe, is that Chris Morrison got a deal on those tapes for Phil as a solo artist.

“I saw Phil and talked to him about it,” continues Archer. “Phil wanted the deal, he wanted to release records. From having a situation where no one would touch him with a barge pole because of the drugs thing, he had this possibility to do this recording. At the time, being where I was and being young, I thought I was being shafted because I wasn’t being kept in the picture as to what was going on.”

A deal was struck with Polydor, according to Salter – two albums firm with a £50k advance for the first one, increasing on the second and options for three more. Tom Dowd (Eric Clapton, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Rod Stewart et al) was pencilled in to produce, but he was impressed with only three songs and wanted to bring in outside writers: “Which didn’t go down well,” Salter says. “Phil’s career wasn’t in tatters. If it was down to the stuff, it was beyond him.”

An album was scheduled to record in March, followed by a tour. First came a single, Nineteen, produced by Paul Hardcastle. A typically raucous rocker, it failed to set the world alight. Lynott, though, was following two trains of irrational thought – one to let his management do their thing; the other to do his own. Which is how he ended up recording Out In The Fields with Gary Moore.

Lynott was notorious for getting his management office to deliver petty cash daily for his own (probably drug-purchasing) reasons. But seeing an opportunity, he decided that he personally would negotiate a deal with Ten Records when he worked with Gary Moore on Out In The Fields. The Grand Slam song, Military Man, was on the flip side. He was paid £5,000 for three tracks (in cash apparently).

Morrison was livid: “The reason he didn’t tell me was that he thought I would take it against the 80 grand he owed my company and he should have known better. I got hold of the Ten contract afterwards and tried to renegotiate, saying ‘this guy wasn’t advised’ etc but we had to swallow it and Out In The Fields came out. It was an atrocious deal. He came in and asked if I could get him out of it. As usual, he was contrite. He was brilliant at working any emotion.”

With 1985 winding to an end, it looked at last as if things were looking up for Phil’s future career, but the partying would not stop, and he seemed the least likely to call it a day. To those around him, this was just what Phil did and he had an aura of indestructibility about him. Undoubtedly, he believed it himself, although those closest to him – his wife and former members of Thin Lizzy – couldn’t stand the baggage he brought with the drug abuse.

Mark Stanway saw Phil shortly after the Grand Slam split and saw little difference in his lifestyle choice: “There were rumours of Lizzy reforming. I’ve never heard quite so many guitarists saying that Phil had asked them to join the reformed Thin Lizzy. I think that Thin Lizzy probably would have reformed. I don’t know who the other guitarist would have been, probably Brian Robertson. Brian used to come over to the house and we would jam together with Phil. There would always be a lot of Jack Daniel’s and other stuff involved. Jimmy Bain would be around and Filthy Animal from Motörhead, partying and jamming. Lots of partying,” he emphasises. Sounds like the rock’n’roll version of The Wild Bunch.

As Christmas approached, Phil and entourage would take in the usual round of record company parties, always looking and playing the part. It was at one of these that he bumped into rock journalist Dante Bonutto, writer for Kerrang! and presenter of the Music Box Power Hour on satellite TV. The modus operandi of getting rock stars on the show was to bump into them and issue a hasty invitation. So it was with Phil. Bonutto was a huge fan of Thin Lizzy and particularly Phil and had never interviewed him before.

Apart from Phil’s partying reputation, though, Bonutto had no idea of the physical condition of the star he would interview that evening.

“I remember wondering at the time why Phil couldn’t get a record deal with Grand Slam,” says Bonutto. “He was struggling. He wasn’t getting the response that you would have thought that someone of his reputation would have got. It was very surprising… because if Phil had survived that period, he would be one of the biggest stars in rock now making records with Bono and Bon Jovi.”

He was shocked at Lynott’s demeanour: “Well, he didn’t look well, a little bit yellow and was a little bit down. Not like the person I had seen hanging out before – the Party Man and great guy. It was just the time he was in… There wasn’t the vehicle for someone like him to appear in, like Classic Rock or a radio station to embrace someone like him.”

Bonutto, a fan of Grand Slam, quizzed Lynott about the failure to get a deal. He couldn’t explain it, though he pointedly noted that “the minute I went solo, people started to offer me deals. Maybe Grand Slam suffered the backlash from Thin Lizzy fans – a band that could potentially be good, against a band that had been around for 12 years with a string of hits. I just don’t think Grand Slam won in comparison.”

The possibility of a Thin Lizzy reunion was mooted by Bonutto, and while not dismissing it totally, Lynott’s priority, he said, was to establish his solo career first “before I start to live off past glories”. He did talk enthusiastically about his forthcoming album. He looked forward to getting special guests to suit individual tracks – Brian Downey, John Sykes and Gary Moore were mentioned. There would be various producers – Tom Dowd and Peter Collins among them.

“In general, it should be more balanced by my other solo albums,” he added, “because with them, I was also in Thin Lizzy who took all the heavy stuff and I got all the fish that John West rejected! My solo albums were much softer whereas this time there will be a better balance with more up front hard stuff and ballads.”

It was to be the last interview with Lynott and Bonutto remembers it with a tinge of regret: “It was difficult for him to answer some of the questions because he wasn’t the guy in Thin Lizzy any more and he missed that. How do you replace being the frontman in a band like Thin Lizzy? It was a little bit strange and a bit sad.

“I felt that he had no answers to why his situation had arisen, no more than I did. Looking back it was just the wrong moment… Things would have sorted themselves out in the long run. It was a really weird period in his life when he didn’t seem sure of what he was going to do.”

Throughout the interview, Lynott’s voice was wheezy and he looked unwell. “Whether he was fit or not fit, I was just thrilled to meet him and I thought he would come through because you always expect people like him to, but everyone is fallible. When you take that warmth of the spotlight away, it must have been quite difficult because he was such a high profile person. He would have had a fantastic career had he survived though, I’m sure of that.”

Just before that interview, Scott Gorham had decided it was time to seek out his old Thin Lizzy buddy again.

“I did some recording in LA,” he remembers. “It had been probably just over a year since I’d seen Phil. I really wanted him to listen to these recordings that I had done and more than that I really wanted to see Phil again. I felt it was time to reconnect and felt I was safe enough to be around people who took drugs.

“That was a main consideration. It’s the first thing you have to do once you decide that you’re done with the drugs, you have to walk away from all of these people that you were taking drugs with or else you’re just going to fall right back into it. The temptation is too great, but I felt strong enough at this time mentally that I could go over and see my old buddy and just have a chat with him and see how he was doing and all that.”

Phil was overjoyed to hear from him, and a meeting at the house in Kew was hastily arranged. Gorham was taken aback by what he saw that morning: “Knocked at the door, opened it and there he was in his robe and pyjama bottoms and I looked at him and I was absolutely shocked at what was standing in front of me. He was totally puffy, his eyes were all fucked up, skin tone was not good at all, and he was wheezing away with his asthma like you wouldn’t believe. With Phil, that was a sure tell-tale sign that he had been hitting the smack pretty heavily. Whenever he did the smack, he would get these asthma attacks, so consequently he was sucking on those inhalers all the time.”

Gorham was still pleased to see him and stayed for three hours chewing the cud. “I put aside how bad he looked. I came in and we gave each other big hugs and we started chatting away there a mile a minute about what we had been doing. I put the recordings on and he really genuinely seemed to like what he was listening to. Then he’d pull out the guitar and say ‘I got this fookin’ song I wanna play you’. You could tell it wasn’t finished at all so nothing had progressed from the old days! And that’s when he started to talk about getting together again and start writing and getting the band back.

“Outwardly I’m going, ‘That’s a great idea’, but inwardly I’m looking at Phil thinking, ‘There’s no way in hell that he’s ready to be on the road at all’. And I couldn’t step into that situation and he knows that he couldn’t do it at that point. He’s looking at me and I’m this picture of health. I’m glowing at this point. And I’m watching him look at me thinking, ‘Fucking hell, man, this guy is fucking healthy’.

"And he’s saying things like, ‘I’m going to get off the gear, I’m going to get healthy again. I’m going to get back in shape’ and I’m saying ‘that’s exactly what you need to do’ because we both know what it takes to get out on the road. You just can’t be out there and sustain any sort of level at all when you’re that fucked up. He knew it and he knew that I knew it and that’s why he was saying those things. But it seemed like he really, really meant it because when he saw how healthy I was, he wanted to be that way too – but [at the same time] he knows he’s trapped.

“A lot of our time was spent sitting around talking about old times, old stories, the shit that we did, how we could have and should have improved things, the way that things got recorded in a hurry. Saying ‘if we were to do it again, we would do it a little bit differently’, those kind of things, friends talking…”

The issue of Lizzy reuniting was talked about, with both agreeing it would be a good idea at some stage in the future. “It was just the health issue at this point, which was a pretty big hurdle. But I didn’t see that it was insurmountable… At least I didn’t think so at the time. I figured that Phil was that kind of guy, if he really wanted it really bad he was going to go out and get it. He knew how I felt – that we had to be on top form to go out and do this. I was in a positive mood when I left that day.

“But it was really tough for people like him to ask for help because that meant you were weak, especially back in the 80s. He pretty much knew that he couldn’t do it himself. It was not going to happen. I couldn’t see him actually doing it, although I believed that he really wanted to be well. I didn’t see how he was going to do it because of the kind of person he was. He wasn’t going to get into seeking help. He was the kind of guy who would never say he was sorry about anything or the kind of guy who would ask anybody for help. So he was really stuck. I just know for me I was fucking desperate and I so badly wanted to come off drugs that I had no problem asking for help.”

A few weeks later, that lack of ability to ask for help rebounded on Phil Lynott. On Christmas Day, 1985, Lynott was found collapsed in his bathroom, having fallen getting out of the bath. His wife, Caroline, was called. She drove 100 miles from Bath where she was spending Christmas with their children, Sarah and Cathleen.

Assuming that Phil’s condition was drug-related, she drove him first to a specialist drugs clinic in Wiltshire, where doctors recommended that he should be admitted to the intensive care unit at Salisbury Infirmary as he was suffering from a medical condition, septicaemia. The infection took hold and he tragically died on January 4, 1986 from heart failure and pneumonia, and the inherent drug problems, after an 11-day fight for his life.

Everyone was shocked at the news. I knew that Jimmy Bain had been due to spend Christmas at Phil’s home and now back in Los Angeles, I phoned him with the news. There was a stunned silence as Bain took the news on board. He said little else.

Scott Gorham remembers: “My wife Christine took a call and she went ‘Oh my god! No!’ And I thought, ‘Holy crap, Phil is dead’. I sat down on the stairs of my basement and just cried. It killed me that he wasn’t going to be there any more.”

“I don’t know if shock is the right word, because I had seen him in some states,” says Mark Stanway. “With Laurence at the house we’d have to carry him and put him to bed.”

Dante Bonutto puts it all in a reasonable perspective: “I was very shocked to hear of his death. You never want to do the last interview with anybody, but I can’t be the only person who thinks that it could have been avoided. Perhaps if I had known him better, someone could have had their arm round the guy and said ‘What’s going on?’ The guy needed some help clearly, instead of doing TV shows. I don’t know the ins and outs, but I just wonder why there wasn’t somebody around to help – or maybe he didn’t want that. I feel that it had to be an avoidable situation.”

Phil Lynott’s heritage is very much alive. Many of those who worked with and/or were close to Phil still have vivid dreams about him. It’s a psychological phenomenon of sorts. My own dream has Phil coming back as a zombie who can’t play or sing. Within a few months, he’s back on the road again as if he’s never been away.

I mention this to Scott Gorham. “Yeah, I did too. Most people who knew Phil dreamt about him. Even people who had only had a casual acquaintance. That’s called having a big impact. My dream is that I get out of the car after being dropped off at this warehouse. I walk in and there’s Phil sitting at a studio console, and I say Phil, for fuck’s sake, where have you been, man?’ And he says, ‘Ah for fook’s sake, I’ve been living with the cleaning lady. I just needed a break’.”

Gorham cracks up at this. “Phil always would have the last word!”

The original version of this feature was published in Classic Rock 154, in February 2011.