The winter of 1977 was fierce on the East Coast of the USA. A thick layer of snow engulfing the territory between Boston and New York, the freezing environment that was to be the killing ground for two of Britain and Ireland’s biggest rock bands: Queen and Thin Lizzy.

Queen were at the height of their creative powers, having captured the world with Bohemian Rhapsody and A Night At The Opera, now consolidating their position with Someone To Love and A Day At The Races.

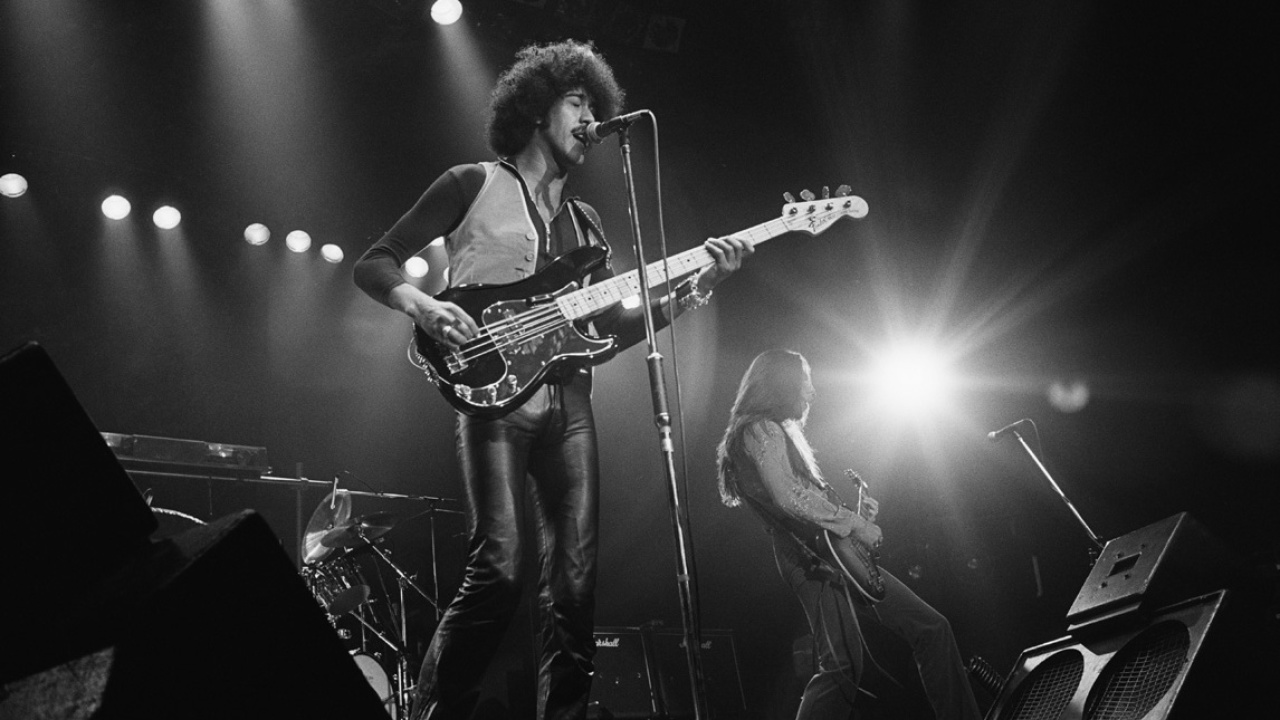

Thin Lizzy, too, were no slouches. The Boys Are Back In Town and its parent album Jailbreak had finally given them chart status, and this was sitting well with an awesome live reputation. Don’t Believe A Word and Johnny The Fox emphasised their intention to stay around a while. Live And Dangerous, which would turn out to be rock’s definitive live album, was just round the corner. It was sheer bad luck and circumstance (on Lizzy’s part) that led to them touring the US with Queen. An earlier tour had been cancelled when Phil Lynott contracted hepatitis just as they were nudging coast-to-coast fame, and when the time came to cross the Atlantic again, guitarist Brian Robertson, a young Scot with an unfortunate attitude, decided to pick a fight with the wrong man in the Speakeasy the night before they were due to fly out. The upshot: a broken bottle slashed the tendons on Robbo’s right hand. Tour off.

Forced to stay in the UK, they went to a party at Advision Studios, where Queen hosted a playback of A Day At The Races. Lizzy guitarist Scott Gorham and Phil Lynott ended up in deep conversation with Brian May and Roger Taylor. Queen were big fans of Thin Lizzy. During photo sessions with Mick Rock, they insisted that Vagabonds Of The Western World, Lizzy’s last album as a trio (Lynott, drummer Brian Downey and ex- guitarist Eric Bell), was played to help them relax. Now, at Advision, both bands talked enthusiastically about touring America together.

With Gary Moore returning to the Lizzy fold in place of Robertson, both bands found themselves in Boston, a city that was special to Queen and especially to Brian May. The band were big mates with Aerosmith, and it was in this city that they prepared themselves for US tours. Lizzy were the support band on the tour, playing an hour-long set compared to Queen’s one hour and 45 minutes. As support, they were under the usual restraints: no thunderflashes, no wandering into restricted areas of the stage marked only for Queen use. One night Gary Moore broke out of Lizzyland and into Queendom, delivering a blistering solo in the process that brought the crowd to its feet. He was warned not to do that again. There was no animosity between the bands, though. Lizzy saw it as a bit of a learning curve.

“There were about a dozen bands that wanted to do this tour with us,” said Roger Taylor. “We thought that Lizzy suited our audience better than any of the others, and they’re probably better than any of those bands anyway. I mean, there’s no point in making it easy for yourself. We wanted a good all-round show. It’s a good tour for both bands anyway. Lizzy playing to tremendous audiences, 10-20,000 a night.

“I’m probably biased, but this is the best line-up around. As a rock’n’roll fan, I would come and see this show if it came to my town. Definitely!”

Scott Gorham was pleased with the match. “It’s a good one for us because we’re playing in a lot of places we’ve never played before and we’re playing in places where they haven’t even played our record, so that’s the challenge. Obviously there’s a bit of competition, but our aim is not to blow the ass off Queen. We got out to blow the asses off the audience and win them over because it’s Queen’s audience, though I’m sure we’ve sold a lot of tickets.”

I joined the Queen/Lizzy tour in New York and was taking in Madison Square Garden, Nassau Coliseum, Syracuse Civic Center and, finally, the Boston Garden. As an avid Lizzy and Queen fan, it was a dream tour. Never having seen Gary Moore during his earlier (brief) stint with Lizzy, I was keen to see how he would fit into the setup. He was a hired gun this time, taking over from the popular Robbo, and now having to play Robbo’s set pieces and solos. How would this sit with Moore? I shouldn’t have worried. Moore’s input reflected his own effervescent style, adding a powerful injection of axe style. He was also an inspiration to Gorham, who seemed content to play second fiddle to Robertson but now came out of his shell.

“I thought it was going to be a real tough one,” Gorham considered. “It took Brian and me two years to get to where we were as dual lead guitarists, and when we decided that Brian was out, I was a little bit more freaked than anybody else. But after just 11 days rehearsal with Gary, it clicked. Brian was more into playing lead guitar, and after a while he lost some interest in the harmony things so we were starting to do less and less of it. But Gary likes it as much as I do, so that reintroduced the harmony guitar work into Thin Lizzy. “Playing with Gary is the happiest I’ve been for a long, long time. It’s like breathing fresh air again. I guess it was kinda getting stale for a while. I know that on the last English tour, I was getting pretty depressed with a lot of those gigs. I would go back to the dressing room and I wouldn’t talk to anybody, and just go back to the hotel and lock myself in there.

“There was really a lot of heavy raving going on. People were losing control of themselves, and it wasn’t making for good music. It seemed sometimes that just a lifetime of noise was coming out, although we did have our nights when we came off and felt great. Brian was drinking pretty heavily, and I was going a bit crazy, too, and Phil, of course, still had hepatitis and he would get depressed.

“So this whole thing is just one big blast of fresh air, where everybody has perked themselves out of the staleness. We’ve got a new vibe in the band now. When we walk on stage, we have a great time again. It’s like a whole brand new thing, with 100 per cent more music coming out of it now.”

It was Thin Lizzy’s first tour of the American East Coast and you could smell the disappointment in the dressing-room after the first gig at Madison Square Garden when they felt that they didn’t do their music justice. They had, said Lynott, treated Madison Square Garden as just another gig. The disappointment was such that Lizzy wouldn’t go back on to do their encore; they didn’t feel they deserved it. It was the same story at Syracuse, in New York State: Moore had difficulty with his guitar, damaged earlier in the day, and never settled down, while Scott Gorham was just a little too laid-back for comfort. Lizzy went down well at both places, but for this band, it’s the sub-standard gig that breeds the excellent one, and it was significant that on the nights following the Garden and Syracuse, Lizzy went on to play concerts full of controlled aggression and anger. They meant business and were taking no prisoners.

This was especially true of the gig at Nassau Coliseum, another one in front of 20,000 fans, and all staunch Queen followers. Lizzy were forced to work hard to win the support of the audience, a challenge they thrived on. They simply battered the crowd into submission, and fully earned their encore. The real clincher at the gig came with the drum solo of Brian Downey during the riffy Sha La La. The crowd wasted no time in showing their appreciation for Downey’s energetic wrestling bout with his kit, and from then on in, it was Lizzy’s gig, ending with Baby Drives Me Crazy, which thankfully evoked the right ‘baby baby baby’ response from the audience, instead of the embarrassing silence of the previous night at Madison Square Garden, and encoring with Me And The Boys Were Wonderin’ How You And The Girls Were Gettin’ Home Tonight – still the best encore in the world and, with Moore adding his own touches, better than ever. The atmosphere in the dressing room was much more positive than the previous night, with Lynott triumphantly announcing: “We showed ‘em. We made an impression tonight all right. Follow that.”

Three nights later they were in Boston, a city they’ve never played before and which, apart from The Boys Are Back In Town, is unfamiliar with their music. This time, Lizzy took only five minutes, and, by the end of Massacre, the second number in the set, they sensed that it was their gig. Lynott, for one, was showing more aggression, and portrayed his tough man persona to the hilt. Playing in front of Queen audiences, there was no real danger that Lizzy would blow Queen off the stage. But they did make Queen work harder than they have ever had to. Queen had been getting a hard ride from the American rock critics this time around, the majority of whom had sided with underdogs Lizzy.

“The local press has been almost unanimously anti-us,” Brian May complained. “But it is very unpredictable, because usually the local guy who gets sent along from the local newspaper doesn’t really know what’s going on. Constructive criticism is healthy but I don’t like the fashionable easy slagging-off that tends to happen a lot, and a lot of these local journalists pick it up from the big guys and they want to be famous, too, so they go in and slag off the big band. I think it’s all on a very childish level.”

Nor are Queen worried that many critics attempt to play them off against Lizzy. They view that as “a false rivalry”. As Roger Taylor said, it was inevitable. May and Taylor, in particular, were close to Lizzy, and often went out drinking together after gigs. Taylor’s allegiance to Lizzy’s hectic lifestyle is obvious, as I witnessed when I went to his room at the plush Plaza Hotel in Manhattan. Taylor had built a Scalextric racing kit through two of the rooms and – suitably lifted by champagne and whatever else was available – he was having the time of his life. The man was a born rock’n’roller. Brian May was a much quieter person and enjoyed hanging out with Lizzy because he is into that type of hard-rocking band. He and Lynott got on very well together, and May was keen to play on Phil’s solo album.

Freddie Mercury and John Deacon, on the other hand, kept themselves detached. Deacon had his wife and child on the road, and that, coupled with his natural tranquility, made him almost inaccessible. Mercury, meanwhile, was playing the star card to the max. At airports he didn’t mingle with the rest of the band or with Lizzy. Instead, Freddie would sit at another part of the lounge, accompanied by his friendly neighbourhood masseur and other friends. And, true to his adorable camp nature, he wouldn’t do interviews, as he explained to me at one after-show party. Eyeing me from the other side of the room, he sauntered over, gave my bum a gentle pat and whispered: “Harry, dahling, I’m so sorry about the interview. But I’m just not giving them anymore… no exceptions.” And with that, he disappeared into his fawning throng.

It’s always dodgy covering your favourite bands, especially if there’s a flavour of criticism. I found this out a couple of weeks after the article appeared in Melody Maker. I’d been to the Rainbow Theatre to see Elton John and spotted Queen’s May and Taylor in the audience. Up I went to say hello. Taylor was his usual affable self. Brian May, on the other hand, had seen my piece and wasn’t best pleased. “Nobody blows us off in Boston,” came the opening salvo. “Boston is our town. Nobody blows us off and Thin Lizzy didn’t. You weren’t even there. You left with Lizzy before we came on.” Which I hadn’t, but what can you do? May apologised for the outburst later, but at least he was passionate in defence of his band. Queen went on to become bigger everywhere else in the world… except the States.

Thin Lizzy never really broke America. Gary Moore threw a tantrum in the middle of the next – you guessed it – American tour and left after one album, Black Rose. Phil Lynott learned one thing from the Queen tour. Having spotted how pampered Freddie Mercury was on the tour, he decided to have some of the same and got more and more spoiled with each subsequent Lizzy tour. Germany, 1979. The Big Man is ruffled. Here we are, 40 minutes into the set. This place should be in uproar. The seats should be reduced to matchwood. The audience is enthusiastic but, apart from a couple of extremists on the wings, remains fixed to the seats. Nevertheless, it’s claimed that they’re enjoying themselves. “Za Hamburg audience,” the promoter assures us, “it is very hard to getzem on ze feet.” Hamburg’s shyness plainly irritates Phil Lynott. Earlier, in an uncharacteristic fit of temper, he threatened to cancel the gig altogether when the local fire chief declared that Lizzy could not use their flash bombs within the hallowed interiors of the Musichalle.

“Tell your boss,” Lynott muttered at a harrassed emissary, “that if we can’t use them then we’re not goin’ on.” Phil’s peculiar outburst wasn’t exactly taken seriously by the rest of the band. Gary Moore was busy outside cavorting with a friend, Brian Downey sipped champagne, and Scott Gorham dozed on the couch – the night he’d popped 10 times the doseage of sleeping tablets that he intended to take. Lynott, though, persisted with the charade, determined to knock the fear of God into the Germans.

His anger had been fuelled by the news that there would be no soundcheck. It would be a late start, 10.30 pm – two hours later than any other night – because in an adjoining hall there was a piano recital and it was feared that this loud rock music might interfere with the audience’s enjoyment. At this announcement, Lynott turned reddish-black with rage. “A piano recital?” He heard right. “No sound-check because of a piano recital! Fook that. We’re usin’ the flashes, no matter what the fookin’ fire chief says. Okay, Finbar.”

Finbar is in charge of the lights and effects. One of his lackeys had just dismantled the fireworks, having been informed that they would not be needed. “A fookin’ piano recital.” Phil strode around the dressing room. “Jesus. We’re a rock’n’roll band, not a fookin’ showband. These people have come to see the full Thin Lizzy show, an’ they’re gonna see it.”

Lizzy went on and used their flashes. Perhaps the hall officials headed for the nearest bomb shelter, because they didn’t interfere with the show. But, by then Lynott had other things on his mind. You could almost hear his brain click: “Jesus, what do we have to do to get these people on their feet? But, by Cowboy Song – “We’re gonna try an’ rock you with this one” – he was obviously overcome by the situation. For a second he stepped out of the spotlight and out of tune. “It’s okay, amigos,” he sang sweetly. “YOU CAN LET YOURSELVES GO!” 10 minutes later, the audience looked as if they were actually enjoying themselves. The relief was palpable.

Backstage, Lynott applied the old football adage. “Wait’ll we get them at home,” he said. Next stop, Saarbrucken, is a sneeze on the road from Frankfurt to Paris, the sort of place you want to beam out of instead of waiting for the next train. If you want to measure Lizzy’s low-key reputation in Germany, consider that I came across Phil Lynott in the car-park, wondering when the audience was going to come, and from where. Lynott and company cast a single glance at industrial Saarbrucken and decided that, instead of staying put that night, they’d move on to Frankfurt 200 kilometres away, after the gig. Throughout the Lizzy organisation, it was generally felt that Saarbrucken might not recover from a night of Philip Lynott. The gig itself was a solid if unspectacular Thin Lizzy performance, most notable for an impromptu version of Whiskey In The Jar.

Ever since that old standard reappeared at Hammersmith Odeon on the last UK tour, its performance has seemed to be an indication of Lizzy’s pleasure with their audience. Later, sound engineer Pete Eustace approached the band about sound problems they’d suffered in the venue. “You and acoustic halls don’t mix very well,” Pete offered. “I thought I was going to get knifed out there. People were yelling at me to turn it down.” Gorham disagreed. “At the front they were lovin’ the hell out of it.” “Yeah, but it’s cannon fodder to them.” Eustace counters, determined to impress his point upon the band.

“At back the cotton wool was falling out of people’s ears.”

“That wasn’t cotton wool,” Gary Moore smartly comments. “That was their brains.” Asked why they played Whiskey In The Jar, after fighting it off for so long, Lynott simply counters that Gary Moore knows the song. But doesn’t it indicate that Lynott’s attitude has mellowed recently? No, claimed Lynott. In the wake of the success of Live And Dangerous, won’t Lizzy find it harder to enforce the continual progression upon which they’ve always insisted? After all, their set was still leaning towards Live And Dangerous – Phil made no apologies for that. “I’m progressing the way I’ve always progressed,” he said. “When we started off, we’d sing everybody else’s numbers. Then, gradually, we introduced our own songs, dropping favourites as we went along, until half the set was original. And that’s what I’m doin’ now, only we’re not goin’ fast enough for certain people. But I’m bearing in mind that we have a very large following of loyal Lizzy supporters – and for us to have a radical change, which we don’t really want to do yet, would be stupid. We can’t totally ignore the fact that Live And Dangerous is our most successful album.

“The next tour we do will be another step away from Live And Dangerous. We’re gonna move away from that era with Brian [Robertson] and into another one with Gary… Dependin’ on how long we stay together. The pressure broke up the band before. It could easily break this one. I don’t think that we’re one of these bands that are gonna last for ever and ever. We could break up at any time… But don’t be writing our epitaphs yet because, as far as I’m concerned, we’re just starting now. Gary, for the first time, has given full commitment.

“I want to develop more as a songwriter and an artist of some sort. I want to get better and better at it, and I honestly believe that I am improving. But whether I actually move at the rate of speed that people want me to is another thing. Graham Parker hit it right on the head – Squeezing Out Sparks. That’s what it’s all about. What I can tell you is that the band is goin’ through a really creative period at the moment. Things are very positive for us.”

A standard criticism of Lizzy is that they lack the ambition to be a truly huge band. Phil refutes the implication outright. “The point is that we reach a climax with, say, Vagabonds Of The Western World. The pressure of success cracks Eric Bell up. He doesn’t want to fly to Paris to mime to Whiskey In The Jar. We do another three albums and we finally get success with Jailbreak. With the success of that album, we just end up talking about drink, fights and love-lives, and I get hepatitis. We overcome that and meantime we’re recording and building again and we have success with Live And Dangerous, which was to seal an era.

“To some casual observer looking in from outside, they can disregard the kids that have followed us all the way through and have made Live And Dangerous a successful album. I’m not talking just about a double platinum album. I’m talking about an album that was artistically very good. Then people say, ‘Now Thin Lizzy have done that, now give its something different.’

“Well, man, if we were to go out and play a totally original set, that’d be a con. I’m not sayin’ that we’re pandering to the kids by goin’ out and playin’ Live And Dangerous every night, but they have made it platinum and we have to play it to them. But, at the same time, we’re sayin’ that we’re gonna do new songs to show that we are a new band; that by hook or by crook, we’ll be droppin’ the old numbers and they’ll he dropped fast and furious. The end of our set will always just be playtime. The serious part is the early part of the set, the first three-quarters, where we’re playin’ for the music.”

I casually enquire of Lynott where Lizzy might go from here. It is, it seems, the question of the year. “A lotta people are worried about where we’re goin’ from here, and constantly they seem to be sayin’ ‘Give us a new direction.’ ‘Do this.’ ‘Do that.’ ‘This is not what we want from Thin Lizzy.’ And I say, ‘Fuck ‘em, every one of them.’ It’s a well- known fact that when a band gets big, they go for the band. The knives get drawn.

“The point is that we have always controlled our own career. And that’s what we’re doing now. Everybody’s talkin’ about Lizzy as a band that’s been around long time, whereas I think that it’s just the start ‘cos Gary’s in the band now. I don’t feel that I should defend Black Rose. From nobody. Black Rose is the start of a change. I can hear a definite change on Black Rose. Our last recorded album was Bad Reputation. There’s a hell of a difference between that and Black Rose.

“Y’know the way people tell you that when you have millions, there’ll be millions of people there to tell you how to spend it? That seems to be the same with success. There seems to be a million people tellin’ us how to use our success. How we should find this ‘new direction’ and how ‘Phil has lost the humour in his writin’.’ I never thought Massacre was that funny a song, you know? I thought it was pretty vicious myself.

“People are sayin’ that they want me to be their joker. Well, I’m no dancin’ nigger for them. Obviously I’m over-reacting because the press has had a field day on me and my private life. I don’t like guttersnipes that take photographs with telescopic lenses. ‘The people have a right to know.’ Bollocks!”

Cookie is a leading figure in the Frankfurt rock community. Once responsible for booking major bands into the city, by 1979 his interest was confined to a couple of clubs. Cookie first met Lizzy when he booked the band, as a four piece with Gorham and Brian Robertson, into the Zoom Club a now-defunct heavy joint in Frankfurt. Lizzy remembered the faith he showed in them, and renewed the acquaintance when they came back to Germany this time round. Cookie had a pool table in the front room of his city-centre home. At 6 am, after a night spent in his club, we’re invited there for a game. Three hours later, Lynott and I have breakfast before going to bed, shattered. I remember him mumbling something like “It’s gonna be a wild three days,” as we say good morning.

The latest Thin Lizzy album, Black Rose, featured a track called Got To Give It Up. It extols the virtues of clean living, with Lynott suggesting that he (or the character in the song) intends to give up drugs and drink, among other excesses. At 9am on a Monday morning, after a night like that, the song doesn’t carry such a sincere ring. “I’m being a bit cynical with Got To Give It Up,” Lynott admitted later in the day. “How many times do you say you’re gonna give something up and you don’t? It’s that perpetual thing where you can’t break the habit. I mean, I’m trying to be really honest in the song. Like on With Love, too. I wanted to achieve total honesty and also write a love song, and I say ‘This Casanova’s days are over, more or less.’ It’s the ‘more or less’ that’s the honest bit. It shows the human elements, the wanting. “When I was writing those songs, those were the moods I was trying to capture. I did mean what I said. It’s honest contradictions. If my life was a simple black and white” – he chuckles at the irony – “if it was just straightforward, it would be easy to write songs. I wouldn’t wrestle with lyrics at all. I would just have to say, ‘I love you, the sky is blue.’

“But it’s not like that at all. It’s all so much more complicated. Got To Give It Up is to do with trying to give up bad habits – when you know that you don’t really stand a chance.” But the song really lays the addiction on the line. There’s so much desperation in its tone.

“Yeah, but it’s not just me. It’s relevant to a lot of people. I try to give these things up. I really do try, with all the sincerity I can, for brief periods, to give it up. “I don’t condone drugs, really, but I know why artists take drugs. They take them to experience, to go to the edge. Why do people climb mountains? To go to the edge. People always want to go to extremes. And if you go to the edge, you must be prepared to fall off. And lots of guys have.” So it’s inevitable?

“Well, some people don’t need it at all – but seemingly all the artists that I rate have, one way or another, gone to the extremes. Some made it back and wrote about that experience, and others didn’t. To this day I’d love to hear what Hendrix would have done, or what Elvis would have done after their experiences.

“Now, lest you are mistaken,” he says, “I myself don’t take drugs.”

Cowboy Song from Live And Dangerous

Thin Lizzy released Live And Dangerous on June 2, 1978.

This feature was first published in Classic Rock issue 83.

Read the Thin Lizzy Buyer’s Guide here.