Long after they had gone their separate ways, original Thin Lizzy guitarist Eric Bell encountered Phil Lynott shopping. “I was walking past a 7-Eleven in London”, Bell says today. “I could see this slim, tall guy with an Afro – but surely not, you know? I walk in and there’s Phillip holding a wire basket with some Domestos in it. I’m thinking: ‘Fuck, if your fans could see you now…’ He’s like: ‘Ah, Jesus! How are ya, Eric?’ We have the big hug, and Phil looks at me and says: ‘You know something? We created a monster. Every gig I play, somebody still shouts for Whiskey In The fucking Jar!’”

Lizzy’s fine reinvention of an ancient Irish folk song proved to be a double-edged sword for them. A stand-alone single in November 1972, Whiskey In The Jar was the group’s breakthrough UK No.6 hit, but it also prompted a directional quandary. Lizzy’s management wanted another folk remake as the follow-up – “It was: ‘You’re in the door, don’t blow it’”, Bell recalls – but Lizzy weren’t keen. Their upcoming third album, Vagabonds Of The Western World was a transitional, forward-looking record which showcased their versatility and vocalist, bassist and main writer Lynott’s burgeoning gift for sometimes poetic, sometimes macho songwriting. More folk covers would be a bad move. It would typecast them.

Vagabonds was released in September 1973. Lynott insisted on Randolph’s Tango as Whiskey’s follow-up single, but it sank without trace. “It was great, but it was a bossa-nova,” says Bell. “We were skint and travelling up and down the country playing gigs, and every time we stopped at services Phil would buy all the music magazines and scan them for a mention of our new single. Weeks passed, and Phil kept looking. Still nothing on Randolph’s Tango. He eventually realised that we’d blown it, and that affected him pretty deeply.”

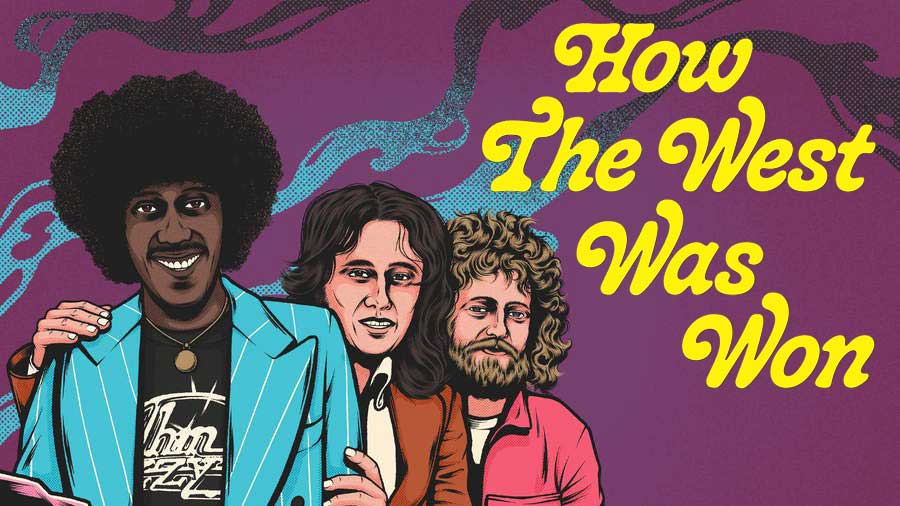

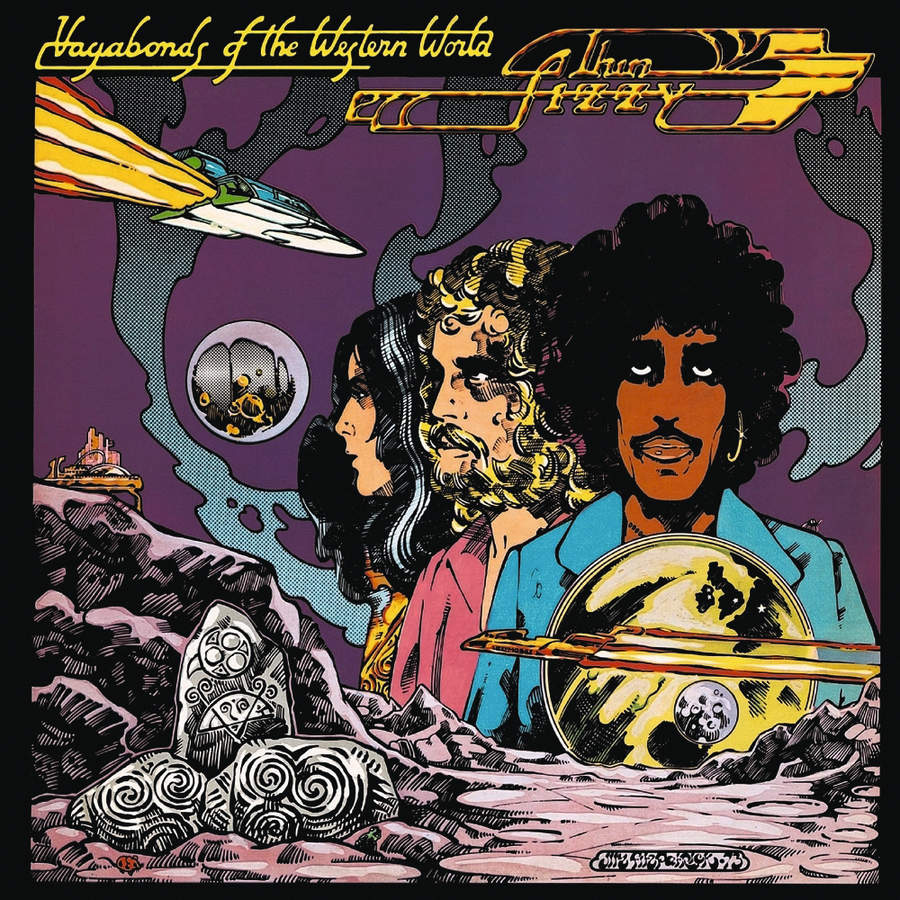

The original Lizzy trio of Lynott, Bell and drummer Brian Downey would implode before the year was out. But that was no reflection on Vagabonds Of The Western World, the recent 50th-Anniversary reissue of which has prompted Classic Rock’s chats with Bell, Downey and the painter of the LP’s ace sleeve-art, Jim Fitzpatrick. Although Vagabonds has perplexed some fans of ‘classic’-era Lizzy LPs such as Jailbreak and Live And Dangerous, it presents an equally captivating, if very different, Thin Lizzy. Vagabonds is ripe for critical rehabilitation, then, but to tell its story we must journey back to Ireland…

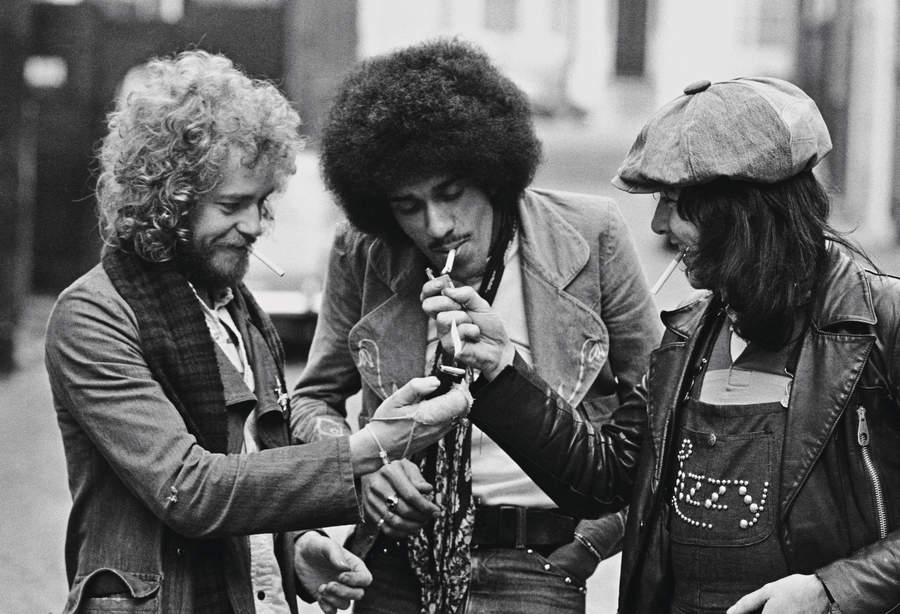

“I’ve lived here in Clontarf for twenty years now,” says Brian Downey, chatting at the North tip of Dublin Bay. “I still pass the house that Phil and Eric rented here almost every day, and I often think about the wild parties we had.” Lizzy’s drummer is referring to the Castle Avenue mansion Lynott and Bell shared with their girlfriends – and pretty much anyone else who wanted to hang out. Downey was still living with his parents then, but he too was at Castle Avenue the night Gary Moore celebrated his eighteenth birthday there.

“Yeah, a guy called Larry Mooney got the plastic bin out of the kitchen, cleaned it out, and mixed up a punch from every alcoholic drink known to man,” Bell recalls, picking up the story. “Me and Gary were on our hands and knees, barking like dogs.”

Bell knew Moore from their shared musical apprenticeship in Belfast. At 17, Bell had played with Van Morrison in Them before paying his dues with Irish show band The Dreams. The latter gig was a good earner which required him to play country, soul and the Top 20 hits of the day. But, seeking a band in which guitar enjoyed the centrality afforded his heroes Jeff Beck and Hank Marvin, Bell settled in Dublin in late 1969 and began scouting for fellow voyagers. Initially the great musicians he sought were nowhere to be found. Worse, his savings were dwindling. “It was: ‘Jesus, what a mistake I’ve made leaving The Dreams!’” he recalls.

Lynott and Downey, friends from school in Dublin’s Crumlin district, had already played in several bands together by the time Bell chanced upon the pair. He’d been out drinking with Them organist Eric Wrixon, and had just dropped his first acid tab when (mostly) covers act Orphanage, who included Lynott and Downey, took the stage at the Countdown Club and blew his mind.

“Phil was so skinny, tailor-made for stardom,” Bell says. “Brian’s drumming was so mature for his age and he got a great sound out of his kit.” The acid was kicking-in by now, bringing Bell’s dreams into Technicolor: “I thought, ‘Wow! These are the guys I want!’”

“Eric came up to us during our break,” says Downey. “I don’t know if it was the acid, but he was very keen, very insistent. We hadn’t heard him play, but the fact that he’d been in Them with Van Morrison was a good marker. He said he’d pay for rehearsals. We were like, hang on, we’ve still got loads of gigs lined-up with Orphanage. Eric was like, fine – finish those and we’ll start a new band.”

With rehearsals and some early gigs under way, legend holds that it was Bell’s playful mimicry of his bandmates’ Southern accents that led the trio to co-opt/reboot the name of The Dandy comic’s girl robot Tin Lizzie.

“We were quickly regarded as a bit of a supergroup in Ireland”, says Downey. But, true as that was, frontman Lynott was still finding his way with four strings, hence his ongoing lessons with Brush Shiels, bassist with Irish blues band Skid Row. Always networking, always broadening his skill set, Lynott was also exploring the more hippy-ish side of Dublin literary life.

“We used to have ‘happenings’,” recalls artist Jim Fitzpatrick. “Eamonn Carr [later of Horslips], Peter Fallon and myself had been in this band called Tara Telephone, and people would get up and read their poetry at our gigs. That morphed into a series of arts magazines called Capella. Marc Bolan and [US Beat writer] Allen Ginsberg contributed, and John Lennon gave us a drawing.

“Anyway, Phillip’s at a happening one night. He’s read some of his poetry, we’re sharing a joint, and he’s intrigued by two artwork posters that are hanging on the wall. We both loved Marvel comics, and Phillip thought the posters were by an American, maybe [Captain America creator/ illustrator] Jack Kirby or someone. But I’d painted them. They had Irish themes and Phil liked that.”

Keyboard player Eric Wrixon was in Lizzy’s earliest line-up too, but he left before their debut single The Farmer (which bombed) was released. Having scored a deal with Decca, the band released their self-tiled debut LP in April 1971. But despite quality, Jimi Hendrix-like material such as Ray-Gun and Look What The Wind Blew In Barber), it too failed to set the heather alight.

Lizzy had a growing sense of stalemate in Ireland. They quickly realised that, if they were to progress, they’d need to be in the eye of the storm. So the whole Lizzy operation (band, girlfriends, roadies, gear) emigrated to humble, dingy digs in North London. “People in Dublin thought we’d made it and were living like kings”, says Bell. “Little did they know.”

The band recorded their second LP, Shades Of A Blue Orphanage at De Lane Lee studios in Wembley. Once again, the word ‘orphanage’ had currency for Lynott. His Guyanese father Cecil Parris had parted ways with his Irish mother Philomena before she knew she was pregnant, hence Philomena and her baby were stigmatised while living in a Birmingham ‘home for unmarried mothers’. Although Philomena adored her son and was always in touch with him, it was his maternal grandmother who raised him in Dublin. He was eternally grateful, and wrote Shades Of A Blue Orphanage song Sarah for her.

Lynott’s very personal songwriting was always intriguing, and his voice was already a wonderful instrument. “He was so soulful”, agrees Downey. “His pitching was perfect, and he’d play with phrasing in a way that always sounded musical and natural.”

Yet, for all Lynott’s obvious gifts, the Shades Of A Blue Orphanage album lacked power and direction. The handful of reviews it received were non-committal or, worse, patronising. “It was a depressing time for the band”, Lynott would later tell music paper Sounds. “We didn’t feel the record sounded like us – it lacked the balls, the energy.”

Lizzy’s unlikely route out of the doldrums was Whiskey In The Jar. Their manager Ted Carroll had heard Lynott and Bell idly strum it at rehearsals, and smelled a hit. Decca needed a single from the band, and Lynott wanted to put forward a new song, Black Boys On The Corner, but was dissuaded.

Bell wasn’t keen to cover Whiskey In The Jar either, but accepted the challenge: how could he reinvent this old warhorse, make it his own? Travelling back from a gig one night, Lynott’s cassette tape of Irish folk legends The Chieftans proved inspirational. “That’s where I got the idea for the intro guitar solo,” says Bell. “The sustained notes were my version of the uilleann pipes.”

The main guitar solo on the single, meanwhile, was Bell’s finest hour. With the rest of the track already recorded, he spent days at home perfecting it. “Meanwhile, I’m getting a three-pronged attack from Decca, management and Phil: ‘When are you going to record your fucking solo?’ Every note was composed, so it fitted like a glove”, adds Bell. “My playing on that song is all about the Irish phrasing – people like Rory Gallagher and myself had it from our showband days.”

Although hopes were high for Vagabonds after Whiskey’s UK Top 10 success, Lizzy were still skint. One day they were hanging with Olivia Newton-John at Top Of The Pops – “She was very complimentary,” remembers Downey – the next it was back to earth with a bang. “When I lived with Phillip in West Hampstead we had baked beans constantly,” says Jim Fitzpatrick. “If we went out for a Chinese meal it was a really big deal.”

Lynott and Fitzpatrick had bonded years earlier – and not just because of their shared love of Marvel comics. “We’d both been abandoned by our fathers,” says Fitzpatrick, “but I just remember us laughing all the time. Phil was a great prankster and a joker.”

Lynott’s inspiration for Vagabonds’ title, Fitzpatrick says, was Playboy Of The Western World. This was the great Irish playwright JM Singe’s 1907 tale depicting the rise and fall of Christy Mahon, who claims to have murdered his own father. “So now Phil wants to reinvent it with this black guy from the Crumlin Corner as the hero,” says Fitzpatrick. “Phillip liked to portray himself as this hard guy, but he wasn’t, really. He was very well brought-up by his granny, and she’d have clipped him round the ear if he wasn’t wellmannered. Irish grannies are lethal.”

When Fitzpatrick was commissioned to paint the cover art for Vagabonds, the broad concept was “a kind of cosmic cowboy or space gypsies thing. I had a rough done which Phillip loved, but when we expanded the design to a gatefold he had some other thoughts. He asked if we could have a bit of old Ireland in there without making it look like a folk LP.”

Fitzpatrick duly added the entrance stone to the Neolithic passage tomb at Newgrange in County Meath, a truly ancient structure built before Stonehenge and the Pyramids, in around 3200 BC. Lynott had learned about the Newgrange tomb’s mystical significance while still at school, and loved Fitzpatrick’s though provoking addition. Still, he had one more request: “He asked me to paint in a spider, a frog and a mouse”, Fitzpatrick says, laughing. “They’re tiny little details. Phil was the spider, with his long legs, obviously, but other than that I don’t know why he wanted those creatures.”

Fifty years on, Brian Downey is able to shed light: “They were our nicknames – Phil was spider, and Eric was frog jaws, because he would pull these daft, frog-like faces. I was the dormouse; our manager, Ted Caroll, had a lot of trouble getting me out of bed after gigs.”

Vagabonds Of The Western World was another case of Lynott writing about what he knew – or wanted to become. Black Boys On The Corner was self-explanatory. Elsewhere, The Rocker was the prototype for Lizzy’s later, mid-to-late-70s band-as-gang zenith. ‘Down at the juke joint me and the boys are stompin,’ Lynott sang, ‘Bippin’ an’ boppin’ and telling a dirty joke or two.’ Here was the future protagonist of The Boys Are Back In Town, already cock-sure, or at least trying to be.

Little Girl In Bloom was more mysterious; deeply personal. Downey and Bell didn’t know it at the time, but Lynott had written it about Carole Stephen, a former girlfriend he’d got pregnant.

“Later on I asked about it,” says Downey, “and Phil told me that Carole had had to go to Cork to have the baby. Then years later, this guy [Lynott and Stephen’s son, now named Macdaragh Lambe] called me up and said: ‘I’m just outside Clontarf. Can we meet for a drink?’ I immediately recognised him at the pub, because he had the same physique as Phil, even some of the same facial expressions. He told me he’d been taken out of an orphanage and brought up in County Kildare. He wanted to know if his mum and Phil had been a one-night stand. I told him no, Phil and his mum had been a couple for around a year. I think he was pleased about that.”

Still consummate road hounds, Thin Lizzy toured the Vagabonds Of The Western World album like their lives depended on it. Third single The Rocker reached No.11 in Ireland in November 1973, but bombed in the UK. Morale became especially low, and Lynott was already considering his options. He even jammed with Deep Purple’s Ritchie Blackmore and Ian Paice on the sly.

Downey remembers Bell and Lynott having “a bit of a scuffle” on tour in Germany. Meanwhile, he was stuck in the middle, ever the diplomat.

“Yes, Phillip was lucky to have Brian,” says Jim Fitzpatrick. “He was kind and a very calming influence. You’d need to shoot Brian in the foot before he would say: ‘Fuck you!’

“Phillip was the main man, of course,” Fitzpatrick adds, “but you have to give a lot of credit to Eric, too. Like Gary [Moore] or Robbo [Brian Robertson], he was a incredible guitarist, but I always thought he was a troubled genius. With the touring, it got up Eric’s nose doing the same thing every night, and I’m not really sure he was cut out for it. And whenever I spoke to Phil, I always got the impression that he was worried about Eric leaving.”

When Lizzy played Belfast’s Queens University that New Year’s Eve, everything came to a head. Bell had the hometown blues and started drinking heavily from early afternoon. When Lizzy went on stage he was blotto; so royally pissed that he didn’t know which song he was blundering through. At 26, Bell was also ripe for a bit of self-sabotage. He threw his guitar in the air and rampaged into his amp and speaker cabinets, kicking them over before stumbling into the wings. A furious Lynott and Downey had to finish the set as a two-piece.

The next day, Lynott told management he couldn’t continue with Lizzy’s volatile guitarist. But the way Bell tells it, he had already decided to quit, and, as Downey acknowledges, there were mitigating circumstances at play.

“You have to remember that Eric’s wife had just left him and gone off to Canada with their son,” says the drummer. “She wasn’t just down in Cork, you know? It was a very upsetting time for Eric, and I think a bit of depression was setting in.”

“Yes, that’s exactly right,” agrees Bell. “I can’t tell you how low I was at that point. I ended up in this poxy little attic, smoking too much dope and spending all my money on cheap wine. Then my doctor prescribed Librium, and that joined the hash and the sherry. Oh my god! I basically left the planet.”

Fifty years on, both Bell and Downey can look back at the Vagabonds era fondly. “There was a time when I thought: ‘Did I really play in Thin Lizzy?’ says Bell. “But now, thank the Lord, those first three Lizzy LPs are being recognised again, and I don’t feel like I’m being written out of the story.”

“Vagabonds Of The Western World is one of my favourite Thin Lizzy albums because it was so diverse, so transitional,” says Downey. “It’s also where you really get to hear Phil the poet.”

In June 1974, Lizzy would re-boot with the vaunted twin-guitar power of Brian Robertson and Scott Gorham, but Jim Fitzpatrick, for one, says we should not forget the magnificence and significance of Lizzy’s first line-up.

“That sound that early Thin Lizzy had, it was very lyrical,” he says. “I loved the stance that Phillip took, and I always thought he had the potential to become a great Irish poet. But the demands of rock lyrics are different, and they need to have an immediacy, which in my opinion didn’t help Phillip. I don’t say this lightly, but I believe he died as he lived: a frustrated artist. Phillip was an Irish Mick who wanted to be a poet, not a rock star."