This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #70.

Thin Lizzy was over. At least that’s how it might have looked to outsiders in 1974.

The Irish band had recorded three albums for Decca and had a surprise UK hit single in the shape of their reworking of folk standard, Whiskey In The Jar. But then it all seemed to fall apart, guitarist Eric Bell left and was replaced by Gary Moore. Moore’s tenure was short-lived and by spring 74 the guitarist slots were filled by Andy Gee and John Cann. Drummer Brian Downey didn’t see a future in this line-up and quit, leaving Lizzy missing an important wheel.

After much cajoling Phil Lynott finally managed to convince Downey to return, and the pair embarked on rejuvenating the Lizzy set-up. With a trio of albums under their belt and ties with the Decca label unravelling, Lynott and Downey now felt a renewed pressure to mould the band into a viable vehicle.

Desperate to find the right man, Lynott finally gave in to his roadie Big Charlie’s repeated pleas that they try a young whiz-kid guitar player from Scotland. His name was Brian Robertson.

Brian ‘Robbo’ Robertson turned out to be hot-tempered with a penchant for fast living, but he would become the all-important catalyst, pushing the naïve Lizzy into the era of raunchy Lizzy. Although the tendency for his lead playing to meander could cause ructions, he was undoubtedly a virtuoso guitarist, providing Lizzy with an instant star.

At the same time, over the other side of the Atlantic, similar possibilities were being explored by a young Californian guitarist called Scott Gorham. After playing in “tons of local bands in Hollywood clubs”, he decided it was time to take a leap. As a means to an end Gorham took on a number of menial jobs in order to earn the money to buy a ticket to get to England.

He recalls: “I got a six-month visa and took a chance. If something happens in six months, great, if it doesn’t, too bad. I took the step and that was it.”

By the summer of 1974 Gorham had been in England for about four months, and time was running out in trying to hook up with a band.

Robertson had his Lizzy audition in early June: “I was actually into Lizzy dating back as far as the Vagabonds Of The Western World album [released in September 1973], so I knew the material. I walked into the auditions and saw those guitarists lined up. By the end of it, it was Downey who gave me the nod, and that was how we started. It turned out that Phil didn’t want to get somebody else in. He wanted to get back to a three-piece. Three-pieces were dead, and I told him. What Phil was writing at that point didn’t really suit a three-piece. In the studio it would’ve been fine, but touring would’ve been impossible. By this stage we didn’t have a record deal, so we had to hit the road to prove our worth. Downey couldn’t see it as a three-piece either, so that put paid to Phil’s thoughts on what route the band should be taking.”

Meanwhile, Scott Gorham was playing around the pub circuit with his newly formed band, Fast Buck. One night saxophonist Ruan O’Lochlaun saw him play. “Ruan dragged me to the side of the stage after a gig one night and mentioned that there was this Irish band called Thin Lizzy looking for a guitar player. I’d never heard of them because they hadn’t really had much success outside of Whiskey… and I don’t think that was even released in America, so my knowledge of them was quite limited.”

After agreeing to the audition, Gorham set off to Hampstead where the band was still in residence at the Iroquo Country Club. With the trio jamming around Vagabonds… material, Robertson, Lynott and Downey were once more losing momentum after a succession of misfit auditions. Thankfully the American arrived just in time on a cold, dark, rainy night:

“I’d have to say my first impressions weren’t all that great… I thought Brian Robertson was an arrogant prick, Brian Downey a complete antisocial who wouldn’t say anything to anybody, and Phil just seemed like a really colourful character who was really upbeat and approachable – but I was still wary.”

Whatever the first impressions, Scott’s guitar playing turned out to be exactly what Lizzy were looking for. The band ploughed through some of their new numbers including The Rocker and Suicide, plus two other numbers that Gorham recalls, “were never actually played again”. With Lynott, Downey and Robertson happy to offer the job to Gorham, the band set about trying to get a record deal. Having parted ways with Decca, the band’s financial position was hardly the envy of others. They were £20,000 in debt. But Lynott’s dedication to the new line-up was total, and the band worked extremely hard to get in shape for some upcoming gigs.

“When I look back now I realise that Thin Lizzy was my first real experience of what rehearsal was all about,” recalls Gorham. “Any of the other bands I had been involved with usually rehearsed for about an hour and after that it was, ‘Fuck this!’. Enough of that and we’d head off. It was my first look at what being a professional musician was all about. We were rehearsing for about eight or nine hours a day, just going at it until we got all the material correct. We were all flattened at the end of each day but it was the right thing to do because by the fourth show we ended up with a record deal.”

At the end of August Thin Lizzy eventually signed their contract with Phonogram’s rock outlet, Vertigo. Through much of September the band were in the studio recording material for what was to become the Nightlife album. With Ron Nevison producing, the band initially thought they had the right man to bring their music into focus.

Because Lizzy had been constantly on the road over the previous year, it hadn’t left time for any ensemble writing, hence Brian Robertson’s torrid memories of these sessions: “On Nightlife we were short on songs, which explains the dichotomy of the material. We hadn’t had any time to write much, so all this Barry White-type stuff started rearing its head. It was the record company that fixed up the ill-fated Nevison partnership.

“Overall though, Nightlife was a weird album. I liked it and still like it – primarily because it was the first album I recorded. There’s a real sense of innocence about the whole thing. There were four different people with a lot of different influences, who didn’t know each other that well and we were learning each other’s thing at the time. Aside of that, we had to deal with Nevison.”

Unfortunately, all involved vouch mercilessly that Nevison proved to be detrimental to their progress as a rock’n’roll outfit.

“Nevison would drive up to the studio in his Rolls-Royce at the height of summer and he’d be wearing a huge fur coat,” Robertson continues. “He was an American twat shouting, ‘Eh hey eh’. I can safely say that Ron and myself didn’t get on too well on that record.”

Gorham agrees with Robertson about Nevison, but is less keen on the music on Nightlife: “I was really disillusioned. I wasn’t real big on Ron Nevison after we finished. It was my first album, as it was Brian’s, and we were two young guys trying to find our way. When you’re in this situation you look to guys like Nevison to help you through the rough spots. He wasn’t that enthusiastic about the music, and probably rightly so because it wasn’t a great album. We hadn’t found our feet yet, so it was a bad experience for all involved. Nightlife to me is more like fucking elevator music to be honest with you.”

Nightlife certainly has its faults, but it marked a significant progression from the previous Decca releases, Vagabonds…, plus Shades Of A Blue Orphanage (March 72) and Thin Lizzy (April 71). With the album due out in November and a new tour to back it up, Philomena was released as a taster. The poetic, maternal tribute was hardly a suitable single for Lizzy, who were selling themselves as a rock’n’roll band, and it failed to chart.

The advance from Phonogram was for two albums and would help clear their debts, as well as fund the cost of a putting a band on the road. It was also time for a reshuffle at Lizzy’s top end, and manager Ted Carroll quit.

Carroll maintained that he left because of the increasing clashes of personality between Lynott the visionary and his new lead guitar player, Robertson.

Robertson, meanwhile, reckons that the same friction that caused Carroll’s departure was also the catalyst for some of the band’s best material.

“Lizzy, like most other bands at the time, had their tempers, all of us did, maybe me more than most, in fact me more than everybody. Phil was mean when he wanted to be, Downey was passive and Scott was your archetypal rocker. The tension in the band was always between Phil and I. Phil needed the aggravation and in my opinion thrived upon it, and what came out of this aggravation were some of the classic Lizzy songs.”

As the band gigged mercilessly throughout the country, once more there was a feeling of dejection as news filtered through of Nightlife’s failure to dent the charts. The gigs were going well, but the lack of chart success only heaped the pressure back on for their follow-up Vertigo release.

In the lead up to Christmas, plans were set for Lizzy’s first visit Stateside early in the new year. The proposal was to tour supporting Bob Seger, ZZ Top and Bachman-Turner Overdrive. It was a short, three-week tour, but long enough to bring on the usual excesses and obscenities, raging drinking sessions, groupies and general good-natured mayhem. The budget for the US tour was minuscule, with the band sleeping in Holiday Inns, sometimes with two to a bed. Two members were also involved in a fracas with a groupie named Star. The incident involved Gorham and Robertson.

“Phil and I ended up at the Holiday Inn with Star and her friend,” says Robertson. “I was sharing a room with Downey, who was trying to watch the boxing match between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, but he kept on at me because I was blocking the view while trying to get it on with Star. All of a sudden she started biting my tongue and wouldn’t let go. There was blood everywhere, then she went for my forehead. It was the only time I’ve ever hit a woman…”

Gorham confirms: “She left his room and arrived at mine. Christ, she ended up biting me, too.”

Robertson continues: “Around six in the morning and the local sheriff is at the door claiming that a woman fitting Star’s description reported to him that she had been assaulted. It turned out [co-manager] Chris O’Donnell calmed him down, told our side of the story and he buggered off.”

Lizzy’s hard-living reputation and ‘tough as nails’ attitude meant that the band were likely to clash with the more restrained Bachman-Turner Overdrive. Robertson recalls the days.

“Those fat Mormon shit-heads. We were slim, fairly good-looking and kicked their ass. We had a lot of angry episodes with them, Brian Downey especially. But they were Mormons – no sex, no drugs, no drink – and then Lizzy happened along. They were convinced we were off our tits, which we were, but at the end of it when it came to playing we kicked their ass every night. We did get the drummer fucked up on one occasion. Basically he was being told what to do, who to be and where to be by Randy Bachman. So we hired four hookers and stuck them in his room just for the hell of it.”

Even so, by the time both groups returned to their respective homes after the US tour, it was decided that they would pair up again for a European leg due to begin BTO had just recently had a huge hit with You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet, but that was a Stateside No.1 – in Britain their status was pretty minimal. It was totally disregarded by Lizzy who went out there every night with the intention of annihilating them both physically and musically.

“The biggest stroke Lynott ever pulled was to get on the European tour with them,” Robertson remembers. “Somehow Phil managed to get the support slot with BTO when they came over to Europe with a red-hot hit in their hands. We went out on that tour with hired gear and we still kicked their ass. After a few dates they asked us to headline and Phil politely declined. They hated the fact that we were going down so well and they ended up hating us much more.”

After the dismal efforts of Nevison with Nightlife, the band decided to produce their next album themselves. A tough move, considering they had only been together a short while, and made all the more difficult when Lynott maintained he was the man for the job. Keith Harwood, who had helped out with Nightlife, also came back into the fold.

“It was basically Harwood that produced the Fighting album,” Robertson claims. “It wasn’t really Phil as such, it was Keith.”

The sessions took place throughout summer 1975 at Olympic Studios in Barnes. Preceding it was a single of Lizzy’s version of Bob Seger’s Rosalie, backed with a new number written by Lynott dealing with racial prejudice called Half Caste. Like the majority of their early single releases, it failed to crack any markets.

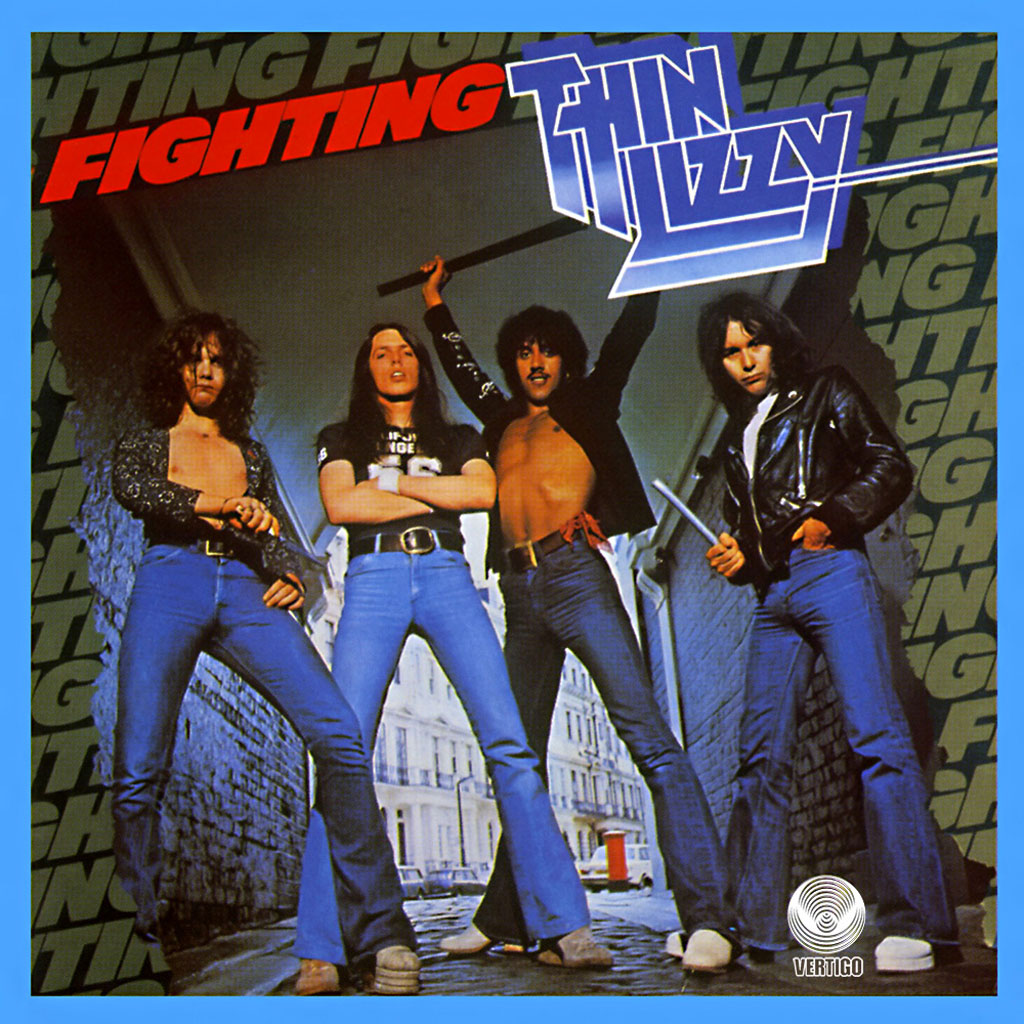

Fighting had already started to take shape. With a larger selection of songs, the band set about choosing the material suited to the album’s title. Clearly Lynott was keen to go for an aggressive feel. In this he had been boosted by [co-manager] Chris Morrison who had witnessed their Roundhouse gig in London on June 22. Morrison suggested Lynott focus his aggression on stage, using it as a weapon as opposed to concentrating on the more mellow aspects of his persona. In the end, some tracks were more raunchy and explicit than others; some as tame as anything they had produced.

For all its flaws, Fighting is a shade better than some of Lizzy’s later albums. The opening power-chord of_ Rosalie_ heralds handclaps and vocal harmonies. Although a boisterous beginning, for some reason the lead guitar sound sounds blunted. Rosalie is followed by the somewhat corny, but melodic, tribute to George Best, For Those Who Love To Live. The footballer had become friendly with Lynott after spending many a night at Philomena’s hotel in Manchester. Best and Lynott would also frequent the same clubs and gradually a solid friendship developed. It was perhaps an ode to the sometimes overzealous and frenetic lifestyle that both men enjoyed, though mostly aimed at a warning. Clearly, neither man was taking any heed whatsoever of the advice: ‘Oh the boy he could boogie/Oh the boy could kick a ball/But the boy he got hung up/Making love against the wall.’

Wild One is Lynott once again cast as a Romeo figure, the lonesome hero as writer. The twin guitar harmonies work splendidly to convey the sad sense of departure in the song. It was intended as a tribute to all those who had fled Ireland during the struggle to maintain independence. Lynott incorporated his own pleas and carefully wove the historical facts into a love story…

The song remains one of Lynott’s best tributes to Ireland and the influence it had on his early years.

On Fighting My Way Back, a defiant Lynott prowls through a vocal that warns the foe that a white flag will never be seen from his gang. Lyrically, Lynott was now constantly using the language of over-indulgence, be it describing the use of alcohol or drugs. Some of Fighting sounds craggy and constipated, and in places falls foul of fickleness and folly, but undoubtedly its bright spots shine as bright as any Lizzy flame. Gorham remains less sure of its appeal.

“By the time it came to Fighting we were getting there,” Gorham maintains, “but it was still a poor album. The pair of them, Nightlife and Fighting, didn’t sell shit because the confidence wasn’t there in the studio. We’d spent more time on the road then anywhere else and the studio was still this unexplored place, so we got caught slightly in no-man’s land.”

With the album set for a late September release, another tour had been booked to take them across Britain, so it was back to the daily grind of rehearsals. With five albums under their belts, both Lynott and Downey knew they needed a hit. They agreed on Wild One as the next single, though the rest of the band claimed little responsibility for it and it sank without trace.

The sleeve for the album was another matter entirely; it is generally acknowledged as one of the worst in rock. Featuring a thugged-up Lizzy, the band posed in a London alley brandishing a shotgun, knife and iron bar while intimating they were ready to take on anyone.

“Phil had a vision that he wanted for the band,” Robertson recalls. “I was too young and too intent on learning what the studio had to offer. Phil was pretty cool with the image and he had ideas on how he wanted Lizzy to be seen by the public. I was never too interested in how the band should’ve presented their look in a photo shoot. Fighting, I have to say, is a very underrated album. Maybe it’s the cover, the worst cover ever to grace an album.”

Upon its release Fighting was the first Thin Lizzy album to chart in Britain, hitting No.60 and selling a reported 20,000 copies. Though still well short of the band’s expectations, it got their foot in the door and enabled them to manoeuvre that little bit more easily. By the end of 1975 Thin Lizzy had the reputation of being one of the hardest-working bands in the business.

During the majority of January and February 1976, Thin Lizzy found themselves holed up at Ramport Studios in Battersea recording their new album with new producer John Alcock.

After the unpleasant experiences in the studio with Ron Nevison on Nightlife and the disappointment with the self-produced Fighting project, it was decided to bring in a calming and encouraging new face as producer. Having already worked with John Entwistle, John Alcock went on to claim the role as guiding producer.

“They asked me to go and see Lizzy performing in some remote corner of the country during a college tour,” Alcock remembers. “After the show we all had one of those uncomfortable backstage meetings where everyone is polite and everyone agrees that a new direction is needed. I agreed to meet Phil a few days later to explore the possibilities of working together. That meeting went well and I liked Phil, plus some of the ideas the band were coming up with were great. I couldn’t help but be impressed with Phil’s enthusiasm and conviction that Lizzy could create a great record.”

Under increasing strain to come up with new material, the two-year old Lizzy line-up of Lynott/Downey/Gorham and Robertson was in grave danger of losing the support of their record company Phonogram; the pressure to produce a hit single and album was becoming unbearable. It was clear that Lynott was coming up with some of his strongest material yet, all that was required was for the band to polish his initial ideas, in what was in essence their last shot at the big time.

“By the time we got to the Jailbreak album, that’s when we thought we’ll start doing demos, so we went out to a farm in the middle of fucking nowhere and spent three weeks out there by ourselves knowing that this was probably our third and final shot.” Gorham recalls. “We knew that we had to hunker down and really work at this thing. We ended up writing 15 songs; we had to whittle it down to ten and we didn’t know what songs were right for the album. One of the songs we were going to leave out was The Boys Are Back In Town.”

As the band put the finishing touches to the record, their thoughts once again returned to what might be the best track to release as a single. “After nearly five weeks of working 15-to-18-hour days,” Alcock recalls, “we got around to mixing the record and we had to come up with suggestions for a single from the album, and we stuck Running Back out to be slated as the first single. Although the choice of The Boys Are Back In Town was suggested as a single it was met with some scepticism as it was felt that the lyrics might not appeal to Auntie BBC. It turns out, we were wrong.”

With a single release in mind some guest musicians were wheeled in to juice up and commercialise a couple of the tracks. It was at this point that Robertson’s arguments with Lynott finally came to a head

“Running Back, for example, what a piece of shit,” snorts Robertson. “I like the song as it originally stood when Phil brought it to me before the rest of the band. I wanted to do it in a blues format, but he insisted it be poppy. I said, ‘Fuck that’ and walked away. On the demo I played piano and bottleneck guitar and it sounded great but Phil and Alcock really pissed me off when they tried to make a single out of it at the record company’s insistence. In the end the song didn’t come to fruition the way they wanted it, so they got Timmy Hinkley in to play keyboards – which I took enormous offence to. I couldn’t understand why they’d pay this guy a fortune of money just for playing what he did. I mean, listen to it and tell me it’s not bollocks. It was a very big stumbling block on that album. In fact I didn’t end up playing on the final version that made the album. That can happen when you try too hard to make a hit out of something. I think if we had gone my way, the song may have done something in the charts.”

The album version of Running Back proved Robertson’s misgivings and is nothing more than light-hearted fluff, a timid piece of romantic rumbling. Romeo & The Lonely Girl followed the same theme, though superior on all fronts. Warriors closes side one in thunderous fashion. It has been said that the theme of this track is drug-related with its warnings and ultimatums. Everything within it suggests death.

Side two opens with an all out rock’n’roll attack. The Boys Are Back In Town provided Lizzy with their anthem in much the same way that Light My Fire did for The Doors and Bohemian Rhapsody did for Queen. Simply, it’s a classic and to think that it very nearly didn’t make the album is a frightening thought.

Fight Or Fall is simply a regurgitation of Half Caste, dealing with the colour issue, but not at all on the same level. Cowboy Song remains a little underrated and proved Lynott was really at home singing prairie tales. It might well have pushed the album into the Top Ten in Britain had it been released as a single instead of Jailbreak. The next track was a return to Ireland as Lynott revealed one of his most tormented of lyrics with the excellent Emerald. Lyrically, it was all about men storming down from the hills, taking up arms and merging bravery with honour. Lynott’s words are superbly punctuated by Gorham and Robertson’s guitar playing. Robertson is keen to stress the contribution that all the musicians made to the strength of the album.

“It’s not the only band composition on the album, everyone put something into all the songs, another Lizzy myth destroyed I guess. With Lizzy it was never down to just the names on the paper, there were contributions from all angles, on all aspects, by all the personnel at the given time.”

The Irish launch party for the album took place in Dublin, an event which is still firmly in the memory of their then label manager Marcus Connaughton.

“The launch took place at the Tara Hotel in Booterstown and back in those days the record companies spared no expense whatsoever concerning food and drink, but that’s where it ended. After making the best of what was on offer at the reception and having a great time we headed off into town; Neary’s [just off Grafton Street] to be precise. When we got to there I realised things were not as they should have been, as did a few of the others, Phil in particular. The evening culminated with our drinks being spiked and the end result was that my briefcase arrived back into work two days before I did.”

With the decision still up in the air over thechoice of the debut single release from Jailbreak, Lizzy flew to the States for an intended six-week tour where they were due to support a variety of stadium rockers such as Aerosmith, ZZ Top, REO Speedwagon, Rush and Styx. In the event, the sojourn in the States lasted for nearly three months. When media reports were more than generous, their American record company chose to put out The Boys Are Back In Town as their new single. It was a shrewd move. The cut gradually got more and more airplay and eventually peaked at No.12 on the Billboard charts, while the Jailbreak album reached the enviable position of No.18. Even though the band had toured mercilessly throughout the UK over the previous six years, it was to be Scott Gorham’s homeland that handed the band international recognition. During the time that Lizzy spent over in the States their asking price per gig apparently jumped tenfold from $500 a show to $5,000.

During June the band were booked to return to America to support Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow but various sources claim that with the increased stature came increased indulgence. Whatever happened on the night before the start of the tour, Lynott was taken ill in Ohio and under strict medical advice was hospitalised. Without letting on to his band mates or management, Lynott struggled to continue, but after a few more dates his condition had deteriorated so much that he started to turn yellow. It was the consequence of infectious hepatitis. Robertson remembers the fiasco surrounding the situation:

“It was a huge kick in the balls for us. We were going to tour with Rainbow. My pal at the time, Jimmy Bain, was Rainbow’s bass player and I was basically looking forward to seeing my mate and going on tour with him. I got to the hotel and the power went as there was a storm brewing outside. Shortly after the manager came up to my room saying Phil was in hospital and that the tour was off. Then one of the Rainbow guys came up and said they’d prefer if none of us came to the gig; the road-crew, management, nobody connected with Lizzy. Later when Phil came back I headed for his room to see if he was all right and the doctor wouldn’t let me in. The place was cordoned off, no entry for anyone. The effect on the band was immense as we were really cooking at this point and had we done the tour I think it would have finally elevated the group to Division One success. Ritchie was going nuts at the whole thing. In my opinion this was just as big a fuck up as me fucking up my hand [in December 1976, which led to a Lizzy US tour being cancelled]. Nobody knows where he got the hepatitis from but he nearly died; it was a real black hole for the band.”

After flying back for a period of recuperation at his mother’s hotel in Manchester, Lynott started to compose material for Son Of Jailbreak. It was an unenviable task for anybody struggling to recover from serious illness, let alone maintain their place on the unreliable ladder of rock’n’roll. For the meantime Lizzy were in the public eye with another crack at the Top Ten, this time in Britain. After the success of The Boys Are Back In Town in the States, Phonogram decided to issue the single in Britain. Released on May 29, the single entered the UK Top 10 and peaked at No.8.

On the back of the single’s success, the album too began to take off and, as a final thank you to the fans, Lynott left his hospital bed against doctors’ advice to perform a one-off gig at the Hammersmith Odeon on July 11. With Jailbreak finally hitting the upper echelons of the charts, Lizzy had made the jump into the next division. Success both at home and abroad brought greater incentives, although it also moved the band onto a new plain of indulgence. For now, they chose to ride the wave, and ultimately build on their success.

“It was really when we got back to Britain when we went from playing to about five or six hundred people at The Marquee to playing to three and four thousand at places like the Hammersmith Odeon,” Gorham recalls. “Lizzy mania was up and down the country; it was great. Then when we got back to America we felt the impact there but bad luck always seemed to be lurking in the shadows when it came to Lizzy.”

A week later Lynott was back in hospital for more check-ups and was finally given the all-clear with strict stipulations regarding limits on his social life. Limits that would sadly prove hard for him to stick to…

Alan Byrne’s latest Lizzy book is available now: Are You Ready? Thin Lizzy: Album by Album, published by Soundcheck Books.