‘Wah… wah-wah-wahwah-waaah… I wonder how you’re feeling, there’s ringing in my ears…’

Another day in spring 1976, another strip mall in the American Midwest, and another blast of Peter Frampton’s Show Me The Way.

Thin Lizzy were touring the US and had stopped to buy cigarettes. Show Me The Way, and its chart-topping album Frampton Comes Alive!, were inescapable. Every time Lizzy got near a radio they heard that ‘wah-wahwah…’ talk-box intro and then Frampton’s audience screaming when he sang the song’s opening line: ‘I wonder how you’re feeling…’

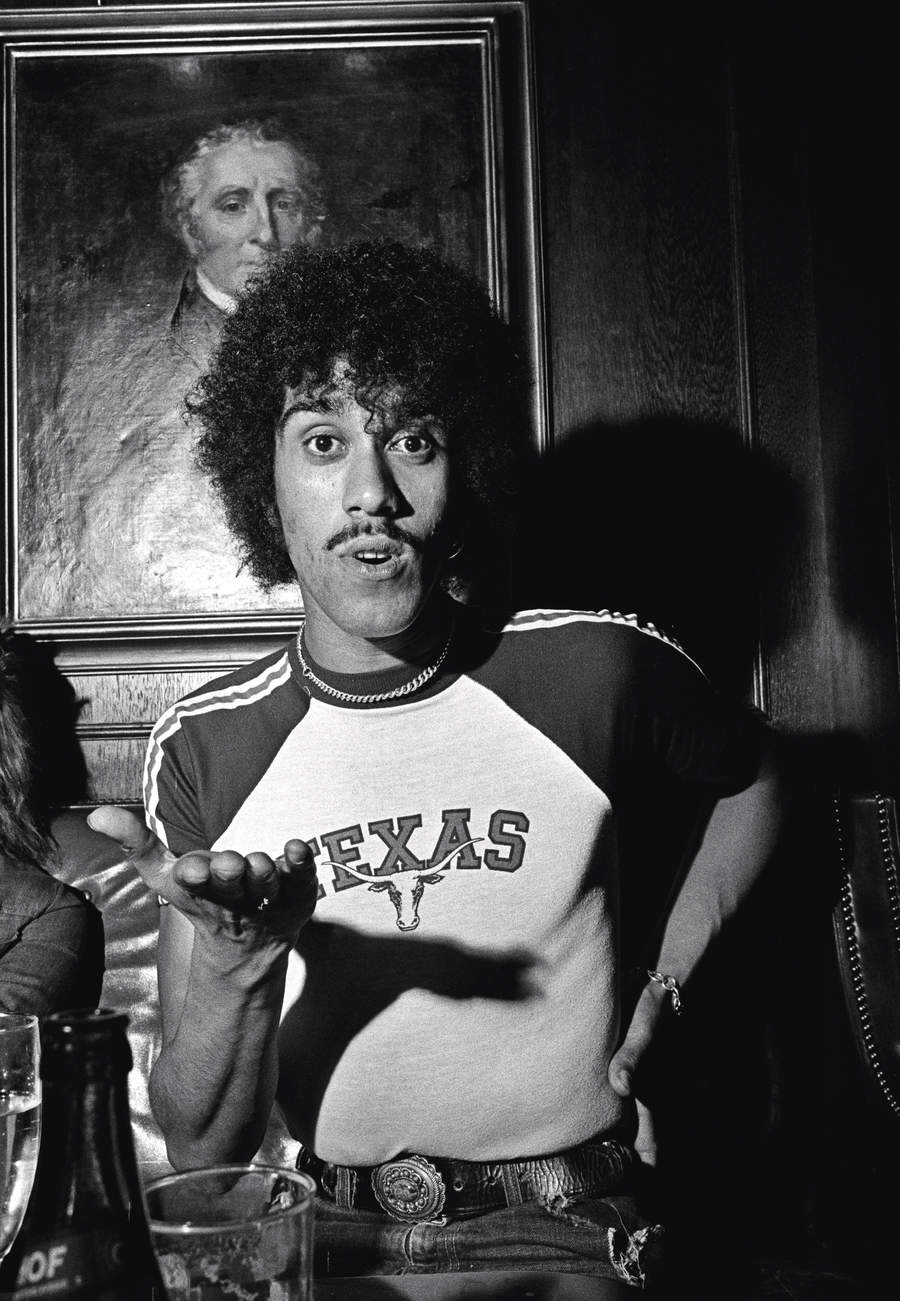

Bass-playing Lizzy frontman Phil Lynott was well schooled in wowing an audience, but Frampton’s noisy reception annoyed him.

“It’s a good song,” says Lizzy’s gatekeeper, guitarist Scott Gorham. “But after hearing it for the millionth time, Phil said: ‘What the fuck, man. Why are they cheering? Is he turning somersaults? Gimme a break.’”

After a pause, Lynott uttered the prophetic words: “We could do that. We could do it even better.”

In June 1978, Lynott’s boast became reality with Live And Dangerous, the album against which all past and present Lizzy releases would be measured. The recent 45th-anniversary super-deluxe edition proves that the answer to the eternal question: Which is the greatest live album of all time?, remains the same.

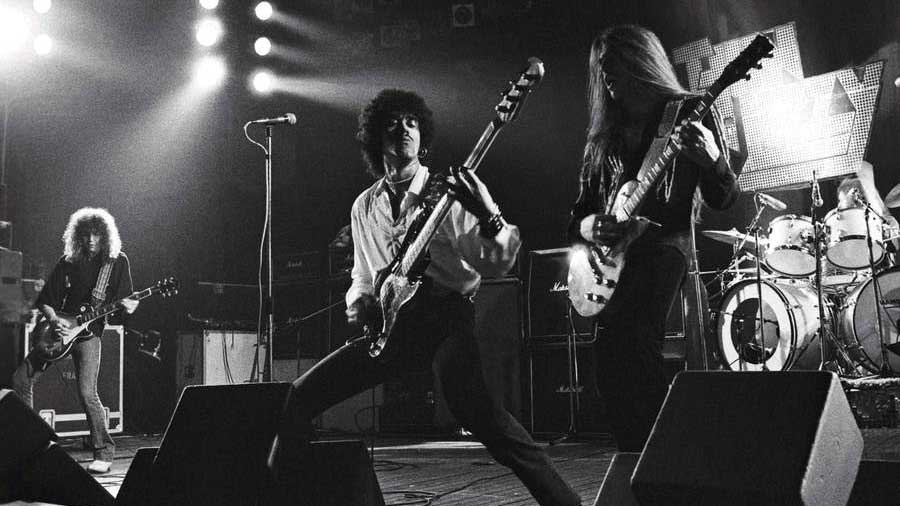

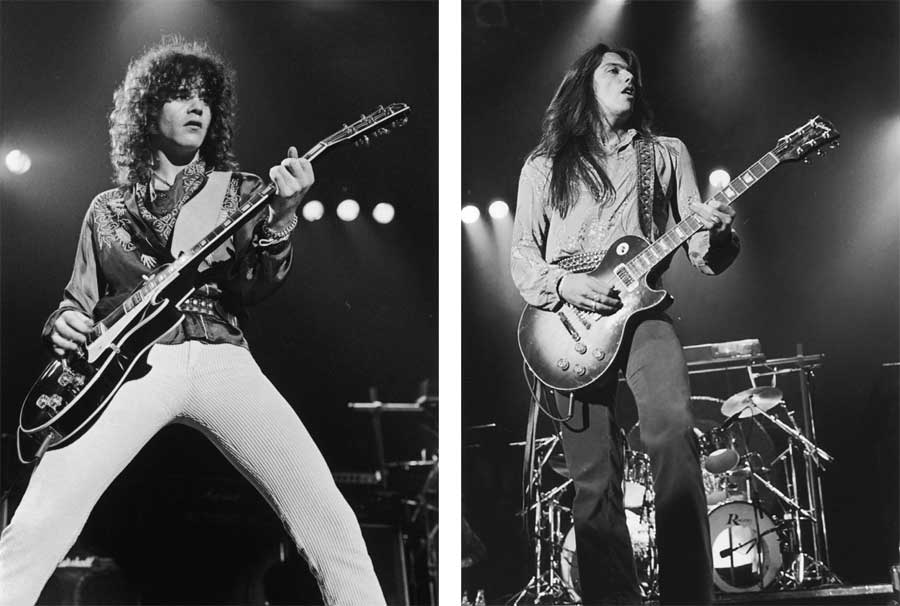

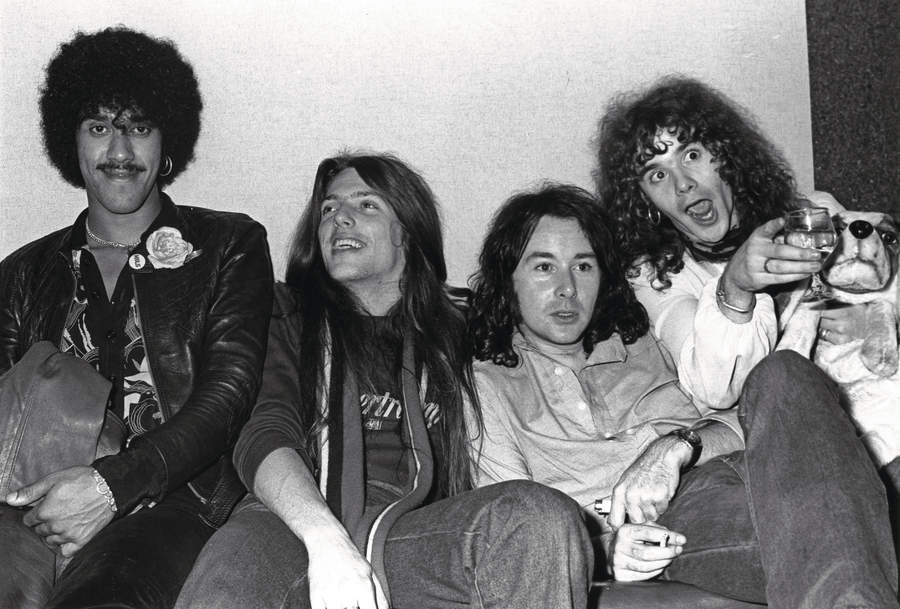

Live And Dangerous captured Lizzy’s on-stage swagger and joie de vivre, but also succeeded in bottling lightning. The ‘dream team’ of Lynott, Gorham, guitarist Brian Robertson and drummer Brian Downey were a combustible mix, and part of what made them such a thrilling live act eventually ripped them apart. Gorham and Robertson, aka Robbo, are one of rock’s great odd couples; like long-divorced parents who don’t talk and only meet up at an offspring’s wedding. Their offspring being Live And Dangerous.

“I loved every second of it and I’m proud of it,” says Robertson today.

“There’s just something about these songs that does it for me,” says Gorham.

A self-professed “uppity little Scotsman”, Robertson has been largely under the radar since his 2011 solo album Diamonds And Dirt. Where Robbo is blunt and critical, Gorham – all silvery hair and beard and smouldering vape – is a fount of polished anecdotes and positive energy. Last month he guested with Black Star Riders (the band who started life as the redux Thin Lizzy) on their tenth-anniversary tour. After which he’s hoping BSR frontman Ricky Warwick and friends will perform as Lizzy again.

The first steps towards Live And Dangerous were taken when Gorham and Robertson joined Thin Lizzy within days of each other. Part-Guyanese, part-Irish Phil Lynott had formed the group with Downey and original guitarist Eric Bell in their native Dublin in 1969.

The Cream/Hendrix-infatuated trio moved to London where their take on the traditional folk ballad Whiskey In The Jar went Top 10 in spring ’73. Then Eric Bell walked out on New Year’s Eve. Northern Irish guitarist Gary Moore was among his temporary replacements, before Lynott found his dream team in May 1974.

Robertson was just 18 and came from a family steeped in music; Gorham was a 22-year-old tearaway with a drug conviction before he fled Glendale, California, for London. Gorham’s brother-in-law, drummer Bob Siebenberg, had just joined Supertramp, and Scott hoped the band needed a guitarist.

“Bobby getting that gig gave me the kick in the ass to work up enough money for a ticket to England,” he says. “Then by the time I had the money, Supertramp’s little Roger Hodgson decides he’s going to play piano and guitar. But I decided to come over anyway.”

Gorham found a £12-a-week gig with pubrockers Fast Buck before he heard about a vacancy in Thin Lizzy: “I thought it was the dumbest name ever – what’s a Thin Lizzy?” He rocked up to his audition in London at the Iroko Country Club in Haverstock Hill with a cheap Japanese Les Paul copy and 30 days left on his visa.

“I’d only been playing for three years, and I remember seeing Robbo and Brian Downey looking at my piece-of-shit guitar. Robbo’s dad played in Art Blakey’s band, for God’s sake. My dad worked in construction and there was no real music in our house. Robbo had all his scales down, and I felt like the underdog.”

Gorham was convinced he’d failed the audition, and was shocked when Lynott gave him the job. “The first thing Phil said was: ‘We’re gonna have to buy you another guitar, and if you stay in the band for six months you can keep it.’”

“I used to have to say to Scott: ‘This is a minor, this is a major,’” Robertson recalls. “Scott used to work his solos out note for note using a little cassette player, and those notes are what he’d play for the rest of his life.”

With gigs and studio time booked, the odd couple had to make it work.

“I brought an American influence into the band,” suggests Gorham. “I don’t want to say ‘country’, but it was a different influence. I got a kinship going with Phil because I was writing and bringing ideas to him. For all my non-expertise, Iwould write things for Brian Robertson to play.”

Lynott was also sold on the idea of two guitarists for pragmatic reasons. “Because if one of those c**ts walks out, there’ll be another one here,” he said.

The new line-up released two albums, Nightlife and Fighting, inside of a year. The first included the future Live And Dangerous ballad Still In Love With You, and Fighting showcased Lizzy’s cover of heartland rocker Bob Seger’s Rosalie and Lynott’s Suicide, both of which also appeared on the live album.

However, life in Lizzy was chaotic, and Gorham learned to referee between Robertson and Lynott. Anything could set them off: a bum note, a riff, a few days’ stubble… When Robbo bowled up one afternoon with the beginnings of a beard, the moustachioed Lynott ordered him to shave, “because I’m the only one with facial hair”. Robertson acceded only when Lynott threatened to fire him.

“Phil and I were always having a bit of to-and-fro,” says Robertson. “He treated me like a little brother – ‘Oh for God’s sake, Robbo!’ And I’d go: ‘Yeah, alright, uncle Phil.’ That sibling rivalry cemented our relationship – personal and musical, all of it. He was never aggressive with me, only when I was out of order, which I could be.”

“Robbo just he couldn’t help himself,” says Gorham. “It was Phil’s band, and that raised Robbo’s hackles. I’d say to Brian: ‘All you got to do is talk these things out and come to an agreement.’ But he just couldn’t come to terms with it.”

By winter 1975, though, the dream team were in trouble. Lizzy’s label, Vertigo, were threatening to dump them for not selling enough records. The following year’s Jailbreak was produced by John Alcock at The Who’s bespoke Ramport Studios in Battersea, in a last-ditch attempt to turn it around. Warrior, Emerald and the album’s title track explored Lynott’s fascination with the outlaw life and spot-lit Gorham and Robertson’s jousting guitars. Lizzy were finally getting there, and even let the label choose the next single.

“Until now we’d always picked them,” explains Gorham. “We’d say: ’Oh yeah, this is going to be huge!’, but every one of them was a dead fish.” Vertigo picked The Boys Are Back In Town, a knockabout tale of boozing and brawling. “It was on the leftovers pile. I don’t think we’d have even chosen it for the album, but our managers liked it.”

On a US support tour with Rush in May ’76, Lizzy discovered that The Boys was receiving heavy rotation on a Kentucky radio station. Other stations soon followed. “These DJs were playing it once an hour, then twice an hour. And then one of our managers walked into the dressing room and said: ‘Congratulations, you’ve got a hit.’”

The Boys Are Back In Town reached No.12 in the US. Then, with imperfect timing, Lynott was diagnosed with hepatitis.

“He’d lay on the floor of the dressing room after a show and the sweat would pool around him,” recalls Gorham. “I’d say: ‘That don’t look too good, Phil…’”

The rest of the tour was cancelled, and Lynott recuperated by writing most of their next album. That album, Johnny The Fox, arrived in October 1976, just seven months after Jailbreak.

“We were always told: ‘Never come off the road, because as soon as you do, everyone is going to forget about you,’” says Gorham. “So it was album, tour, album, tour…’”

“Jailbreak was the seminal Lizzy studio album – that and Johnny The Fox,” believes Robertson. The album was filled with more tales of deadbeats, derring-do, doomed romance, sex and war. Its single Don’t Believe A Word reached No.12 in the UK, giving Thin Lizzy another much-needed hit.

However hard they tried, though, the group never quite nailed it in the studio.

“Call it ‘red light fever’, I just don’t know,” says Gorham, sounding exasperated. “We saw other bands doing it, but we couldn’t capture it. When we discovered that a live album counted towards our four-album deal, we decided if we can’t do the business in the studio, we’ll show people we can do it on stage.”

Lynott wanted a memento of Lizzy live, and Robertson wanted something comparable to his favourite live album, Humble Pie’s Rockin’ The Fillmore. Plans were made to record Lizzy’s three-night run at London’s Hammersmith Odeon in November ‘76. (All three dates are included in the super-deluxe edition, and are testament to how magnificent Thin Lizzy were when creative differences were put aside for the good of the band.) The final night culminated with Lizzy tearing through their early single The Rocker, followed by an after-show bash populated by various Sex Pistols and rock’n’roll footballer George Best.

Then the wheels came off again. A few days later, on the eve of another US tour, Gorham received an early-morning call telling him Robertson was injured. The guitarist had visited the Speakeasy, a musicians’ watering hole in London’s West End, and run into his friend, singer Frankie Miller. The house band, Gonzales, invited Robertson on stage to play. A drunken Miller gatecrashed the performance. There was a scuffle in the dressing room, and Gonzales’s guitarist Gordon Hunte lashed out with a broken bottle. Robertson stuck out his left hand to protect Miller’s face, and the glass ripped through his palm, severing a tendon and an artery.

“I said: ‘Oh come on now, Gordon!’ I never expected a fellow guitar player to do that.” A blood-soaked Robbo was taken to hospital in Paddington and stitched up. Lizzy’s road crew were already in New York preparing for the first date, and Gorham’s suitcase was packed.

“Phil phoned me, furious. What the fuck was Robbo doing down the Speakeasy the night before an American tour?”

“I’d gone for a pepper steak,” says Robertson. “All these writers were later saying I was out of my head on whisky. I didn’t have any whisky. I was living in absolute squalor with two groupies in Kilburn, putting fifty-pence pieces in the meter just to keep the gas on. Are you going to sit there all night, or go down the Speakeasy and get a pepper steak?

“I shouldn’t have been down there that night, I know,” he admits. “But I certainly wouldn’t have reacted any differently in that situation. It took a long time to recuperate, but I actually thought it was good, because it slowed me down. I started going back to the blues… so every cloud, and all that.”

Gorham pleaded with Lynott not to be too hasty, but he fired Robertson anyway.

“He had to,” says Robbo. “How can you play with one hand?”

Lizzy were forced to postpone a second US tour in six months, but Lynott was determined to get back there as quickly as possible.

“It was like somebody up there said: ‘Here’s the deal. We’re going to give Thin Lizzy the rest of the world, but you cannot have America,’” suggests Gorham. “Our bad luck there was phenomenal.”

Gorham craved recognition in his homeland, but says “Phil also wanted to be massive in America”. Lynott’s love of the culture seeped into his writing: in name-checks for ‘First Street and Main’ in Johnny The Fox Meets Jimmy The Weed, and ‘Dino’s Bar And Grill’ in The Boys Are Back In Town. Lynott was thrilled to discover that Bruce Springsteen liked The Boys Are Back.

“And I just heard Bob Dylan is a Thin Lizzy fan,” claims Gorham. “Yeah, Bob, but where were you when we needed you, man?”

Instead, help came in the shape of stately British rockers Queen, who invited Lizzy to open on their spring 1977 US tour. Robertson had to have his wound restitched three times, because he kept pulling off the bandage and trying to play guitar. But Lynott wouldn’t take him back. Instead he hired Gary Moore for the Queen dates.

“The first time I ever properly met Gary Moore was at the airport,” recalls Gorham. Moore and Lynott had a complex relationship. “The day Phil tells me we’re having Gary, he’s getting into a car and gives me a warning: ‘You’re gonna fall in love with this guy.’ Then he rolls down the window and says: ‘But don’t ever trust him’, and drives off. Thanks, Phil.”

Did Lynott have an issue with guitar players?

“In actual fact, I think he had a love affair with guitar players. If he could have had his druthers, he would have been a guitar player. Hendrix was his hero.”

As predicted, after the tour Moore returned to his regular gig with jazz-rockers Colosseum. Lizzy’s live album was abandoned temporarily, and the band prepared to make their eighth studio album, Bad Reputation, instead. Their management had landed T.Rex and David Bowie producer Tony Visconti, and hoped he’d sprinkle some fairy dust over Lizzy. However, Gorham was still angling to get Robertson back when they began work at Toronto Sound Studios.

“I never wanted Lizzy to be a three-piece,” he insists. “Tony kept telling me: ‘You got this, Scott.’ But I purposely left out three solos, and kept badgering Phil – ‘We got to get the dream team back together.’ We had another week left in the studio, and he relented – ‘Alright, man, we’ll get him back. But remember, it’s not if, it’s when he fucks up, man. And it’ll be your fault.’”

Robertson reluctantly flew out to Toronto to finish the album. “But I was on a lot more than just three tracks,” he says.

Released in June 1977, Bad Reputation was another UK Top 5 hit. With Robertson reinstated, but under heavy manners, work resumed on Live And Dangerous. Three more dates were recorded on the subsequent tour: two at Philadelphia’s Tower Theatre, and one at the Seneca College Fieldhouse in Toronto.

Tony Visconti was surprised to be asked to produce Live And Dangerous. Bowie even more so, when he discovered his producer was delaying his next album, Lodger, to work on a Thin Lizzy live record. The truth is, Visconti loved the band, but not their increasingly parlous lifestyle.

“The drugs were taking hold at that point,” says Robertson.

“I wish I could have been more like Brian Downey,” admits Gorham: “’No, I’m not into this cocaine and heroin thing…’”

Nevertheless, Visconti signed up for the task of wading through 30 hours of live Lizzy, recorded on different kinds of tape at different speeds and by different engineers. Which is when the rumours began about how live Live And Dangerous really is.

In early 2020, Gorham was introduced to the former guitarist in a big 80s pop group, who told him that his previous band overdubbed most of their live album because that’s what Thin Lizzy did with Live And Dangerous.

“They’d heard that seventy-five per cent of Live And Dangerous was overdubs,” Gorham marvels. “I got kind of angry, and I probably shouldn’t have, but I said: ‘That’s not the point here. You make a live album to prove how good you are as a live band’ – and Lizzy was a great live band.”

The source of the ‘75 per cent’ rumour was Tony Visconti. “I was totally gobsmacked when I heard that,” says Robertson. “Tony was a great producer and a cool guy. He was at my wedding, for fuck’s sake… I couldn’t understand why he said that.”

“It’s bullshit,” Gorham concurs.

Nevertheless, mistakes were rectified during the mixing at Studio Des Dames in Paris. Visconti says that Lynott re-did most of the bass, prompting Gorham and Robertson to correct some of their guitar parts. Some backing vocals were also re-recorded. And when Gorham tried to fix a dropped note, the band discovered it was easier if they re-did the rhythm track.

“I was worried about cheating,” Gorham admits. “But Tony said everybody did it.”

One error couldn’t be erased, though, and it’s been bugging Gorham for more than 40 years.

“There’s a big old hairy clam on Still In Love With You,” he says. On the night of the recording, Gorham was at the front, throwing shapes. Two women in the front row began massaging his leg. “I thought: ‘Now this a great perk when you’re doing your business.’ But then I had to get back to my pedal board and they wouldn’t let go.”

When they finally did, Gorham lost his footing and dropped a note.

“It’s because Scott had those big red flares on,” adds Robertson.

In the studio, not even Visconti’s sleight of hand could fully disguise the glitch.

“It’s a bad edit,” says Gorham. “And I can still hear it.”

They were also short of material for a double album, and didn’t want the likes of It’s Only Money and Soldier Of Fortune on the (original) record. Instead, Visconti suggested plugging the gap with Southbound from the sound-check at Philadelphia.

“Again we said: ‘Really?’ I guess we were kind of naïve,” says Gorham.

Asked by this writer in 2020 how much of Live And Dangerous was overdubbed, Visconti replied: “It’s been so long since I worked on this album, I can’t specifically say what they replayed… But the percentages I’ve been quoted as saying were an estimate and would vary from song to song… I love Live And Dangerous.”

The record-buying public shared his affection, and made it a No.2 UK hit, kept off the top only by the soundtrack to the hit film Grease. Live And Dangerous was the sound of Thin Lizzy roaming free, untroubled by “red-light fever”. Emerald, The Boys Are Back In Town and Don’t Believe A Word sounded like a band, in Gorham’s words, “flying on adrenalin”.

So convincing was it, Gorham later forgot that Rosalie wasn’t a Lizzy original.

“I knew it was a Bob Seger song, really, but it felt like we’d made it our own,” he says with a laugh. “The original is too slow.”

Live And Dangerous also précised Lizzy’s easy mix of machismo and vulnerability. For every Massacre or Warriors there was a Still In Love With You or a Dancing In The Moonlight (It’s Caught Me In Its Spotlight), the latter one of the greatest songs about fumbling adolescent romance.

Lynott’s piratical charm and showmanship was in full effect too. It’s impossible to listen to the original Emerald without thinking about of its un-PC live-album intro: “Is there any of the girls that’d like a little more Irish in them?”

Even today, when Thin Lizzy play those songs, audiences instinctively mimic Lynott’s Live And Dangerous ad-libs: clapping their hands the way he told them to (“And I move my fingers up and down, up and down…”) or doing their best ‘coyote call’ during The Cowboy Song.

“That was Phil’s power – the way he could connect with an audience, says Gorham.

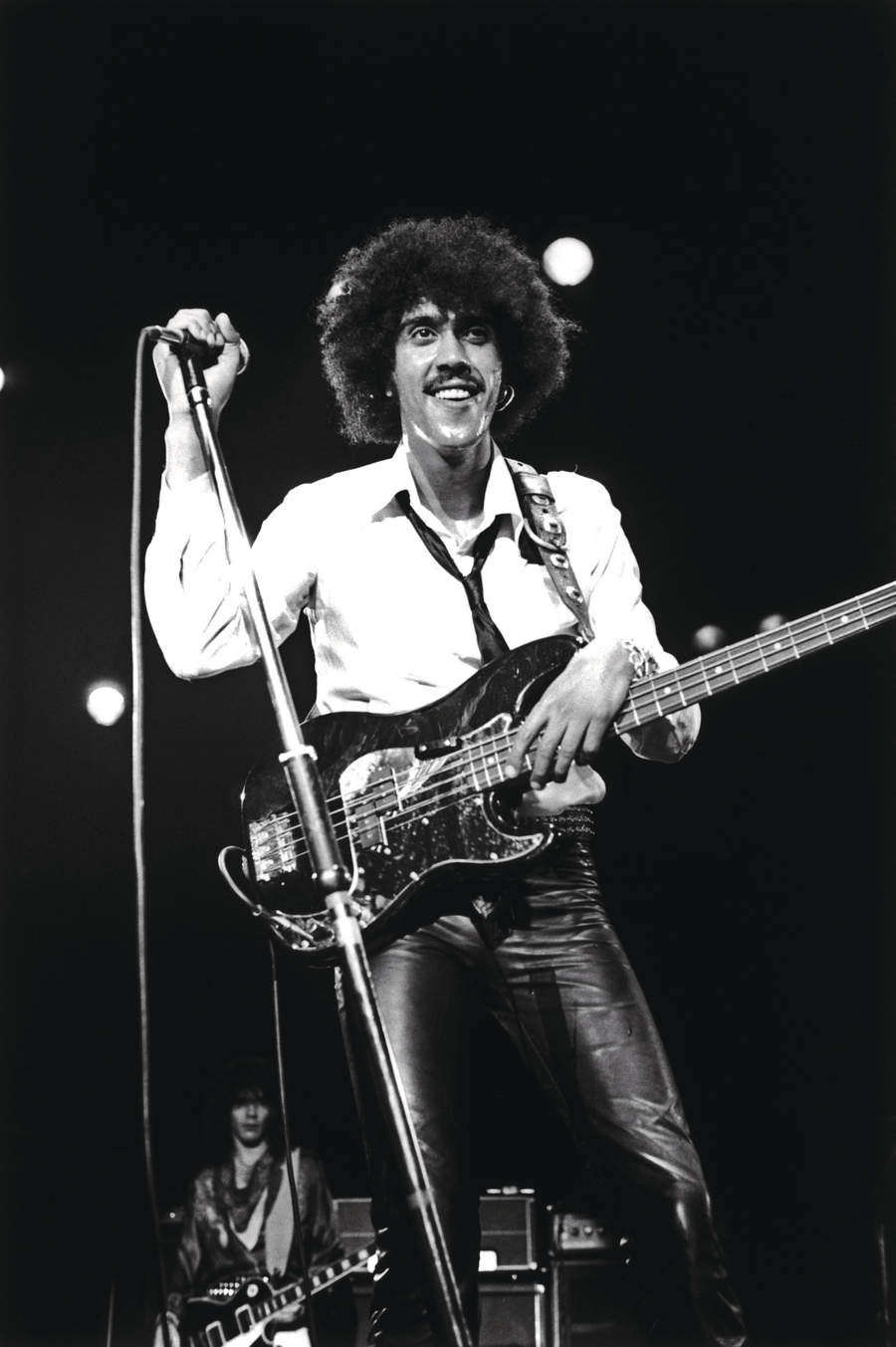

The final touch was photographer Chalkie Davies’s arresting cover shot, showing Lynott, leather-trousered legs spread, cradling his bass and staring into the middle distance.

“Phil never wanted that as the cover photo,” reveals Gorham. “He kept saying: ‘Thin Lizzy is a band’, and we kept saying: ‘Yeah, but just look at that photo – that’s the one."

The impression of Thin Lizzy as a gang was compounded by the photographs on the inside gatefold and inner sleeves. Naturally, Gorham’s red flares made an appearance. The group’s co-manager Chris O’Donnell had attended a piano recital at the Royal Festival Hall, where he watched an audience member follow the pianist’s notes on a musical score.

O’Donnell suggested 17 photographs on the gatefold, one from each song, so listeners could follow the music. The eighteenth photo was chosen by Lynott and showed straw, a razor blade and a rolled-up banknote – a glimpse of the recreational habits that would eventually derail him.

In true Thin Lizzy style, they even toured the live album, culminating with two dates at London’s Wembley Arena. Then Lynott and Robertson clashed again.

“Brian fucked up, but I can’t remember what happened,” says Gorham. “I’m not trying to keep secrets. I was always defending Brian, but I just couldn’t defend him this time.”

It was a culmination of too much fighting, boozing, drugging and challenging Lynott’s authority. Robertson played his last gig with Thin Lizzy at the Ibiza Music Show on July 6, 1978.

“It was a sad moment,” says Gorham. “I never wanted to see Brian go.”

Does he regret parting ways with Lizzy?

“Yeah,” Robertson replies flatly. “The Lizzy sound is Jailbreak, Johnny The Fox and Live And Dangerous… I don’t know if we were great, but we strove to be great.”

“We developed that sound together – me and Brian. We tore it up,” says Gorham.

With Robbo gone, Lizzy reunited temporarily with Gary Moore, before adopting a heavier sound in the early 80s.

“It was all a bit ‘Zzzzzzzz’ and ‘widdly widdly’ for me,” Robertson protests. “Lizzy were never heavy metal.”

In 1983, though, Robertson saw The Comic Strip Presents Bad News Tour, a TV comedy in which ‘Vim Fuego’, played by Ade Edmondson, tells fellow guitarist ‘Den Dennis’ (Nigel Planer) that their group, Bad News, are hard rock, “not heavy metal”.

“And it really hit home, because that’s exactly what I’d been saying in interviews. And I thought: ‘You’re a twat, Robbo,’” he says, laughing. “But it’s true; we weren’t like Judas Priest going [growling] ‘Breaking the law, breaking the law…’”

There aren’t any plans for Robertson and Gorham to reunite when Thin Lizzy go back on the road. In fact, Gorham once compared the pair’s relationship to “sticking cats in a burlap bag”. “But people always ask me: ‘Who was the guy you enjoyed playing with the most?’ And my answer is always: ‘Brian Robertson.’”

The rebooted Live And Dangerous is the musical equivalent of viewing a Hollywood blockbuster from new angles and gorging on the deleted scenes. Its songs are still the foundation for every Thin Lizzy show.

“Really, there isn’t a damn thing I’d change about it,” says Gorham. “It’s not perfect, but it’s us. It’s a piece of history.”

Has he ever told Peter Frampton how much his live album inspired them?

“No, I never have,” he says, grinning. “But if he’s reading this: ‘Peter, thanks for Show Me The Way. We owe you.’”