In August 2011, Roger Waters’ old friend Nick Sedgwick died from a brain tumour. Most Pink Floyd followers had probably never heard of Sedgwick. But days later, Waters posted a message on his Facebook page, expressing his sadness and his plans to publish In The Pink (Not A Hunting Memoir), a book Nick had written about Pink Floyd, but which had never appeared in print.

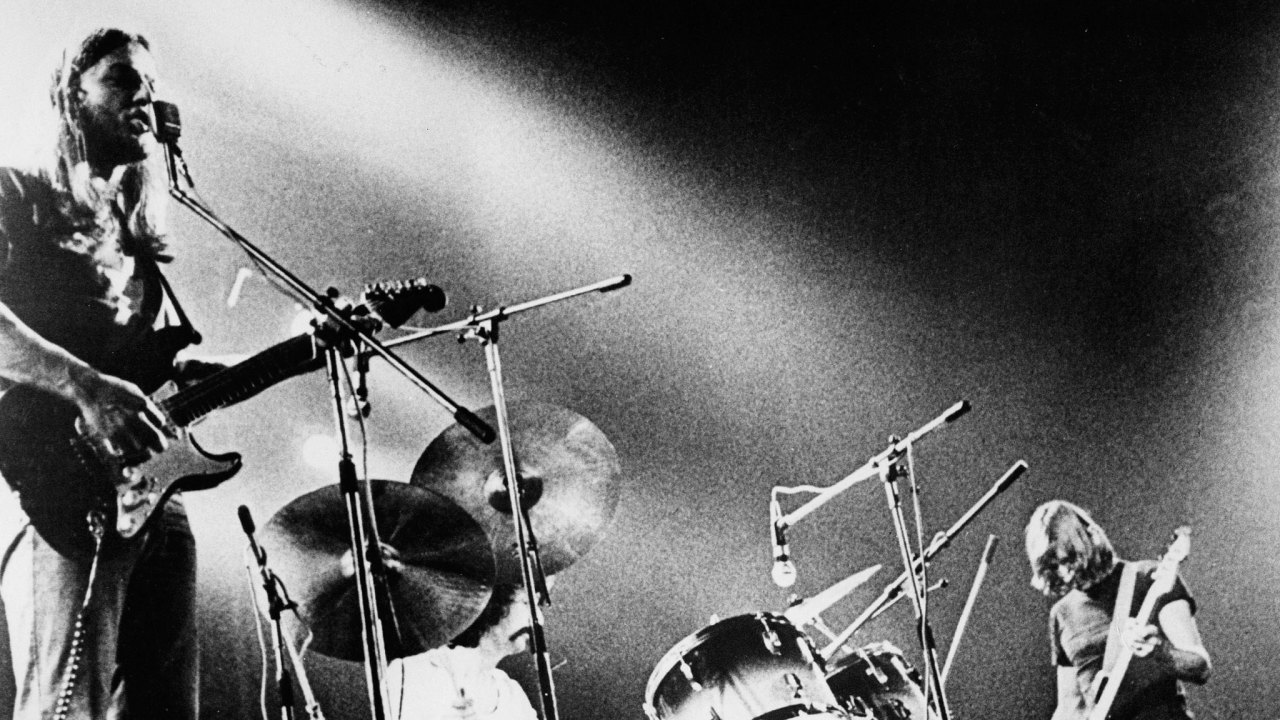

Sedgwick grew up in Cambridge with Waters, David Gilmour and Storm Thorgerson, and accompanied Floyd on their 1974 UK tour and spring ’75 dates to promote Dark Side Of The Moon. “He carried a cassette recorder on which he recorded many conversations and documented the tour,” wrote Waters. “When Nick finished the work in 1975, there was resistance in the band to its publication. Not surprising really as none of us comes out of it very well – it’s a bit warts and all, so it never saw the light of day.”

In an earlier interview, Waters claimed Gilmour had vetoed its publication. Interviewed in 2011, the guitarist admitted feeling “aggrieved” when he read the manuscript, and said, “I managed to get it canned.”

In his Facebook post, Waters promised to fulfil Sedgwick’s last wish and publish the work. He said it would be made available as a downloadable version, a hardback book and a super-deluxe limited edition. To date, In The Pink has yet to appear in any format.

Waters’ statement that “none of us comes out of it very well” is true. In The Pink portrays Pink Floyd as uppity, resentful and a bit bored, with Waters the most uppity, resentful and bored of them all. Floyd’s Nick Mason once said the notion of pop groups happily co-existing “like The Beatles in the film Help!” was never true. But in 1975, it’s arguable Pink Floyd’s audience were willing to subscribe to that myth. Had it appeared then, In The Pink would’ve been a shocking exposé of the fragile egos and relationships inside one of the world’s biggest rock bands. Forty years on, it’s less of a shock. Anyone who remembers Waters and Gilmour needling each other in the press in the 80s and 90s won’t bat an eyelid at Sedgwick’s stories of dressing-room spats and post-gig sulks.

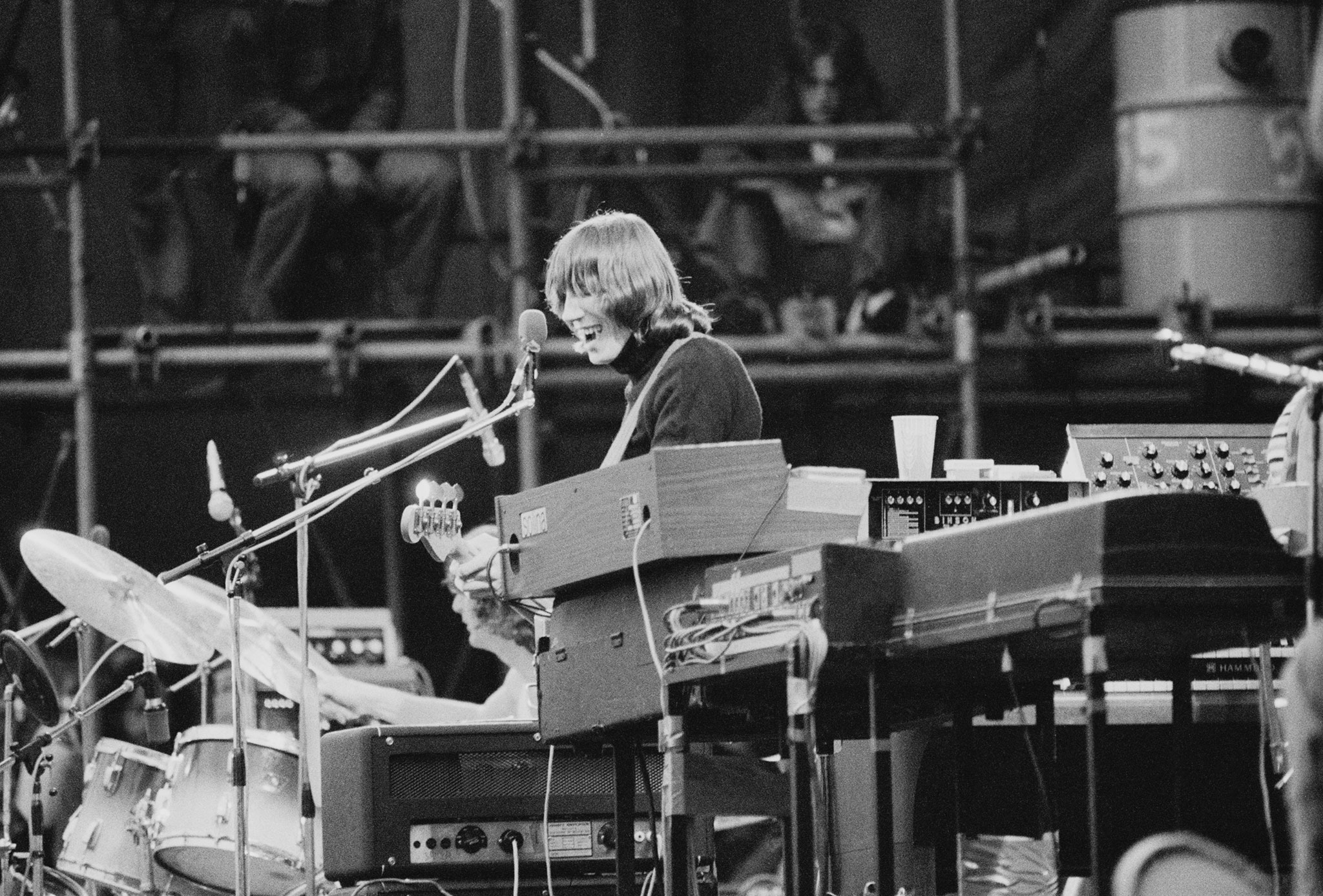

Floyd’s ’74 tour programme featured the band members as comic-strip characters, which magnified aspects of their characters. In The Pink does the same. Waters emerges as miserable and despotic; Gilmour as laid-back, stubborn but ultimately reasonable. Rick Wright wanders in and out like a bit-part player in his own story and Nick Mason seems more interested in his newly purchased Ferrari than playing drums in Pink Floyd.

In Sedgwick’s account, Gilmour accuses Waters of “sounding patronising” when he addresses the audience. Waters worries that at 30 he’s too old to be performing to an audience of teenagers. After being heckled by a fan who doesn’t care for Floyd’s new sounds, Waters witheringly asks, “What do you want me to do?” To which his verbal assailant replies: “Play music!”

There are many observations in the book that could apply to any touring rock band: the road crew get antsy “because nobody’s getting laid”, and everyone greets a backstage cocaine dealer in the US like a long-lost friend – until he’s dispensed his wares, after which he’s scrupulously ignored. Syd Barrett obsessives can also add Sedgwick’s account of seeing Barrett at Abbey Road to the pile of existing anecdotes. Apparently, Syd told Floyd their new song, Shine On You Crazy Diamond, sounded “a bit Mary Poppins”.

It’s not all withering sarcasm and ennui. The book does have its funny moments. On the ’74 tour, NME ran a critical review of Floyd’s Wembley Empire Pool show, in which writer Nick Kent complained about David Gilmour’s unwashed hair. Sedgwick recalls the group’s wonderfully laid-back and very American backing singers Venetta Fields and Carlena Williams giggling at Floyd’s uptight Englishness and the offending NME review. “I can’t believe what they said about Dave’s hair,” marvels Fields.

Nobody comes out of this book very well. But nobody comes out of it worse than Roger Waters.

However, In The Pink comes in two parts. The second part deals with Floyd on tour. The first is a very candid fly-on-the-wall account of a holiday in the Greek islands circa 1974, on which Sedgwick plays gooseberry to Waters and his first wife, Judy Trim. This, not the tour story, is the most shocking part of In The Pink.

Judy Trim really was Waters’ childhood sweetheart and the girl next door, living in the house next to where Roger lived with his mother and brother in Cambridge. Trim, a potter and teacher at a tough North London state school, was married to Waters until 1976.

Sedgwick reveals how Waters’ infidelity on a US tour caused friction in the marriage, and recalls every argument between the two during their Greek vacation. Trim describes her husband as “invulnerable and remote”, and complains that too many summer holidays – and even their honeymoon – were spent with friends or the rest of the band. Waters, meanwhile, seems thoroughly disenchanted by his newly acquired fame and wealth, and is convinced his wife will end up cheating on him. Later, Sedgwick recalls Waters phoning home from the Seattle Hilton on the ’75 tour and hearing another man answer the phone, an event he later wrote into the story of The Wall.

Reading In The Pink, the first thought that comes to mind is how Sedgwick could bear to stick around and witness someone else’s marriage falling apart. The second is why, even though Judy Trim died in 2001, Waters would want this material in the public domain. Then you remember Roger Waters has been bleeding all over his audience since Dark Side Of The Moon – and David Gilmour hasn’t.

If In The Pink tells us anything about Pink Floyd, it’s how different Waters and Gilmour are. It figures that the brutally self-critical Waters would want to make his marital strife and intra-band bust-ups public 40 years after the event. Waters writes about himself; it’s what he does. You suspect as long as Gilmour, the keeper of the Floyd name, has anything to say about it, In The Pink will remain unpublished. More’s the pity. Nobody comes out of this book very well. But nobody comes out of it worse than Roger Waters.