Ian Gillan is sanguine about many things, so it’s no surprise he’s not getting too stressed about the impact the global pandemic has had on Deep Purple. Their twenty-first album, Whoosh!, was originally due to be released in the early summer, when the band were supposed to be on the road. But global events meant the album was put back to August and the tour rescheduled for October 2021.

“These things happen, there’s no point getting worked up about it,” says the man who once claimed that he never had any ambition and was content instead to drift through life with a stupid grin on his face. “It’s an old maxim: musicians don’t get paid for making music, they get paid for waiting around. So we’re quite used to it.”

He’s not being flippant. The singer and his bandmates – drummer Ian Paice, bassist Roger Glover, guitarist Steve Morse and keyboard player Don Airey – all seem of the same mind when they call in over the next few days from the various points of the world where they’re currently enjoying what should hopefully be the final stages of lockdown (Gillan is in glamorous Lyme Regis).

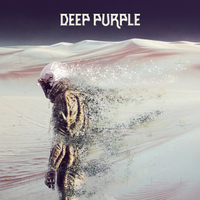

But then nothing about Whoosh! is as expected, not least its existence. Purple’s previous album, 2017’s InFinite, was teed up as being their final one, the launch pad for a tour christened The Long Goodbye. InFinite and its predecessor, 2013’s Now What?!, represented an unexpected late-career hot streak for the last of hard rock’s original holy trinity still standing: albums that combined stateliness and playfulness in a way that only a band of Purple’s stature can manage. Produced, like its two predecessors, by Bob Ezrin, Whoosh! continues in that vein.

When somebody suggests you make a new Deep Purple album, do you think: “Oh God, not again?”

No, no, no. Quite the reverse. We went through a time years ago when everyone seemed under the weather for whatever reason, then everyone felt a bit better and the energy came back, When that’s there, you’ve just got to find an outlet for it.

Whoosh! is like the last two Purple records in that it sounds like a bunch of mates having a good time.

Absolutely right. Everything is done together. We write the songs together, we arrange them together, we record them together. Hopefully that joy and immediacy comes across. You can’t recreate it artificially.

There are some funny lyrics on it. In No Need To Shout, you sing: ‘You stand there on you soapbox without fear, chanting like a demented auctioneer.’

It’s a broad pop at politicians.

Anyone in particular? Boris? Trump?

Not really. They’re all useless. They come in full of idealism and vigour, within five years they’re talking rubbish. It’s the same with musicians.

Another song, What The What?, sounds like an old-fashioned good-time rock’n’roll song.

It’s a road song in a different form. It’s about how things were – pianos in pubs, riverboat shuffles. I was looking for a nice phrase, and of course the first thing that came to mind was: ‘What the fuck happened to you last night?’ And then I thought: “It’s not really Radio 2, is it?” Not that it’s going to get played there.

After Little Richard died, you posted a really touching tribute on your website. Does the death of people you look up to affect you?

I’ve got a little rule in my life, that I wrote about Jon Lord in the song Above And Beyond: ‘Souls having touched are forever entwined.’ So this physical departure, it wasn’t so emotional. It was: “Thank God they’re still with me.” I don’t cry very often, though I did when Pavarotti died. I was close to him.

Were you really?

Yeah. I sang with him twice and got to know him fairly well. He was a regular bloke. He called me at home before the first time we sang, and said: [adopts Italian accent] “So we sing a song together. What shall we sing? Child In Time?” I went: “Thanks, but not really. How about Nessun Dorma?” It went quiet on the phone. And then he went: “Nessun Dorma? You wanna sing Nessun Dorma? With me? You fucking crazy!” He wanted to be a pop star. That was behind everything he thought of. He wanted us to make a record together of covers.

Wow. How far did you get? Did you draw up a selection of songs to cover?

No. It was just in conversation. I don’t think it would have been a good idea.

You’ve talked about recent albums putting the ‘Deep’ back into Deep Purple. It’s a great line, but what does it actually mean?

Deep is the opposite of shallow, and I think that’s what I was getting at. I think we lost the plot to a certain extent for a while, especially after [1984 comeback album] Perfect Strangers, because we’d not really followed the ethos of the band that was so successful. And that was to be brave and bold and write from the heart. A hint of commercialism crept into the band. Which is why I left in '73, anyway.

Why did you lose the plot?

Ritchie – brilliant, but he had an ear for a commercial tune. He had an ear for the more popular stuff. And it was very successful. But I thought it couldn’t survive, because it was planting itself in a fashion, and fashions come and fashions go. Once you’re out of fashion, you’re out of fashion. When it became focused on the more commercial elements, we started writing songs. Anyone can write songs. The thing about Purple was that it was always about finding something exciting to do. The diversity of the influences of the musicians – from orchestral compositions to big-band swing to blues, rock’n’roll, soul music – there was enough energy and music there for a lifetime.

When did you get the energy back?

When Steve Morse joined the band [in ’94], the damage started to be repaired because at least we were working among ourselves again. But I think it was [producer] Bob Ezrin who was able to say: “If you just want to write songs and record them, forget it. I want to get back to where you were in 1968 – bold, not pandering to radio.” And it was fantastic. Suddenly we had somebody who took the reins.

Last year was the fiftieth anniversary of you joining Deep Purple. Did you have a party to celebrate?

[Laughing] I don’t even have parties to celebrate my own birthday. To be honest, nobody in the band was even aware of it. We don’t think about things like that.

Didn’t it even give you pause for reflection?

I hate to disappoint you, but no. There have been so many anniversaries: joining the band, making In Rock, making Machine Head. They all have their place in history, but we don’t sit around thinking about stuff like that. We all have full and active lives away from the band.

You could have retired, had an easy life. Why are you still doing all this?

Retire from what? We’re not doing regular jobs. [Thinks] I can’t find anything better to do. It’s just so amazing. It’s so full of excitement.

So no retirement for you or Deep Purple?

The moment my physical energy goes is the moment I won’t do this any more. We’re realists. We’ll know when it hits us in the face.

Deep Purple are too gentlemanly to get tangled up in bragging rights over the band’s name, although if anyone has a right to claim it it’s drummer Ian Paice. The only member who has appeared on all their albums, he joined the band as a freshfaced 19-year-old back in 1967. Paice is phoning from the UK, although he doesn’t specify where. The enforced clearing of Purple’s decks for the next 12 months doesn’t seem to have thrown him too much. “Whatever we were going to do this year, we’ll do next year. The problem is so will everyone else. It’s going to be quite congested.”

For a band who were talking about making their last album two albums ago, Whoosh! sounds very lively.

Now What?! was a breath of fresh air. For the first time in a long time we actually enjoyed being in the studio. It was a breath of fresh air having Bob there, getting us to create a record efficiently and quickly. I spent ten days in Nashville and then got the hell out of there. InFinite took seven days. This one I was there for eight days. If you make records quickly they generally come out okay. It’s when you take forever that you end up with something that’s perfect but no good.

Have you been guilty of that in the past?

It can happen… Deep Purple is like a bunch of privates in an army with no generals. Everybody wanders around doing what they want to do, and nothing gets done. Back in the day, there were five pairs of hands moving the faders up and down: “My bit’s more important than your bit.” That doesn’t happen with Bob. If he says: “We got the take”, you don’t argue with him. We’re the privates, Bob’s the general.

Have you ever thought: “Oh no, not again”, when someone has suggested recording a new album?

I used to. Hanging around in the studio and doing nothing is soul destroying. Especially when you hear it and it doesn’t sound very good. I don’t think any of us have enjoyed it like this for a long, long time.

That title, Whoosh!, is that what Purple’s career has felt like? That the past fifty-plus years have gone by in a flash.

Domestically, yes. When it comes to family stuff, it’s flown by. But in terms of the band, no. I can remember all the times, good and bad. But there are other ways to look at that title: the things we’ve been going through for the last couple of months, the problems we’re creating on this glorious little ball we live on. We could be here and gone that quickly.

There are some great lyrics on the album. Does Ian Gillan get the credit he deserves as a lyricist?

If he wasn’t in the genre he is, he’d have been listened to in a little more detail. But that doesn’t stop it being interesting, vibrant.

Purple have always had so many things in their sound: rock, jazz, R&B, classical. Does it frustrate you that some people couldn’t see past the long hair and volume?

No. As long as it was called hard rock. We minded when metal came up, because that’s not what we did. Some of what we did spawned it, and I’m quite proud of that, but Purple was never a heavy metal band. It had so many strings to its bows. Maybe it was detrimental to our success.

Purple have never been the cool kids. Your fans love you, but you’re not venerated by the wider world, like Zeppelin or Sabbath are. Does that irritate you?

No, not at all. I’m happy that enough people liked us back then to create this mystique and longevity, and that people still like us today. You can’t do something for fifty-odd years unless you’re doing it right.

A section of Purple fans still want to see Ritchie Blackmore back in the band. Do you wish they’d just let it go?

No, because Ritchie has an incredibly loyal fan base, and a lot of them are convinced that Ritchie is the only reason that Purple became successful. But it comes down to this: we didn’t make him leave the band. He decided to leave and do his own thing, one of which, Rainbow, became incredibly successful, and good luck to him on that. And now he’s gone to something else, which hopefully he’s happy with.

But nobody’s getting any younger. Don’t you ever get the urge to phone him and go: “Fancy a chat, just for old times’ sake?”

It’s not the sort of guy Ritchie is. I’ve had so little contact with him in the last few decades, I wouldn’t know where or what he is any more. The last thing I got from Ritchie was a Christmas card about twenty years ago. No return address or anything. I’ve never cut myself off from him, we just don’t talk. Two different guys with two different lives. If I saw him I’d be very pleased. I’d sit down and have a drink and chat about the good shit. What’s the point of remembering the bad shit?

Speaking of the good shit, is it true that last year you didn’t celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Ian and Roger Glover joining the band?

I think we all forgot. I don’t think we even got together for a drink. Hopefully we can do it on sixty.

Reckon you’ll make it?

I doubt it. But you just don’t know.

It’s 3.30am his time when Steve Morse calls. “I’m a late-night person,” he explains, self-evidently. A few hours ago he was up in the skies above his adopted home state of Florida, in his own plane. He learned to fly years ago, and even pulled double duty as a commercial pilot in the 80s. “I still go up every day,” he says. “Just before sunset, usually. The view’s wonderful and everything looks so perfect up there. You can go here, you can go there, you can tell the machine to do whatever you want.”

Morse has less control over the machine that is Deep Purple, something he accepted from the start. “I still feel a little bit outside of it,” he says. “I sort of feel like I’m a roadie in a lot of ways. Like I’m helping out, I’m part of the show. It’s really about the history the band has.”

Whoosh! is the seventh album you’ve done with Deep Purple. Is it still fun?

Oh yeah. There’s nothing about it that’s too serious – listen to songs like And The Address and What The What. I feel like the Ians and Roger don’t feel right unless we’re getting near a recording/touring cycle again. I remember asking Rog: “Why don’t we just do a song every few months and release it on the website. Why does it have to be such a big production?” And Roger says: “Because that’s what we do.”

I’m guessing that Purple are a band steeped in traditions.

Yeah. There are some things you just don’t do. Like making a change in the set-list, or inviting somebody to ride in the van. And you don’t keep people waiting. If you’re on time in Deep Purple, you’re late. I’m not joking.

How do you actually go about getting a job in Deep Purple? What’s the interview process like?

I was just as worried about the band as they were about me. I was like: “Are these guys just living on the name? Is this just a nostalgia thing? Can they still play?” We just jammed, with absolutely no plan. I played something, Jon Lord played it back. I played something else, he played it back and added something to it. Pretty soon everybody joined in, and I realised these guys are jazz-level improvisers. That’s still the same today.

What state did you think the band were in when you joined?

I think the press certainly was kind of embarrassed that there were these guys over the age of twenty still playing rock’n’roll. I witnessed this alienation in their home country, and I didn’t like it.

Was it daunting for you?

The only thing that surprised me was that some of the fans really just hated me. They thought I was the reason Ritchie wasn’t in the band any more. On my first UK tour, people were throwing shit at me.

When did it stop?

Oh, 2022 I hope. No, the throwing stuff after about a year and a half. Ian Gillan was wonderful, just very loyal and protective. I think that kind of stopped them. There’s always going to be people who think the way it was is the way they want it to be. But it’s been twenty-six and a half years. You think people would go: “Maybe we can cut the guy a break.”

Have you spoken to Ritchie Blackmore since you joined?

Never. I’ve never met him. I’ve listened to the stuff he’s done with his wife, the acoustic stuff. Which I like.

As a Purple fan, would you want to see every surviving Purple member on stage together one last time? Not just Ritchie, but also David Coverdale, Glenn Hughes, Nick Simper, Joe Satriani…

Oh, if they could do a reunion or a gig or a party or a special event, and have it not be stressful, that would be wonderful. The time we did the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame thing, the mediator part of me came out. I was, like: “I wish you guys could just do something and hug each other and deal with it for a day. I want you guys to have closure in a good way.” I really wish that for the guys.

Do you see it happening?

Unfortunately, no. I think the only way that would happen would be if somebody died.

What about you? Do you see a day when Purple aren’t part of your life?

My retirement will be for health limitations. I have arthritis, and I’m learning techniques to make playing possible for as long as I can. When that happens it’s not going to be a happy day. These guys, they’re like some kind of alien civilisation. They go like the Energizer bunny. They can’t be stopped. I’m more afraid I’ll drop before they do.

Do you think there’ll be another Deep Purple album after this one?

Given the history and the levels of activity, I think that’s very possible.

'Uncle Don’ is what his Deep Purple bandmates sometimes call Don Airey. It’s easy to see why. The Sunderland-born keyboard player is affable personified – a trait that has helped him survive stints working alongside some of the trickiest characters in hard rock, from Gary Moore to Ritchie Blackmore.

His 18-year-and-counting stint with Purple is the longest time he’s spent with any band, and he’s aware that even this has to come to an end one day. Although when exactly that will be isn’t clear.

“I was digging through my memorabilia the other day and found something that said: ‘The Long Goodbye Tour, 2017’, he says.

It wasn’t the Long Goodbye Tour, though, was it?

It was. It’s just a longer goodbye than we thought. No, I thought we were going to wind it up. I think the plan was to do a few dates over the next couple of years here and there and that would be it. Of course, the dates keep rolling in once you say you’re available. It’s pretty much out of the band’s hands.

Were you surprised when the band decided to make this new album?

We didn’t expect to go back in the studio, but everybody was ready for it. We had a lot of material, everybody was up for it.

And you had Bob Ezrin.

He doesn’t brook any delay, there’s no excuses. The job gets done no matter what. He’s brilliant at corralling you all together and setting you on the same path. I don’t understand how he does it. He’s at least two steps ahead of me.

Was that discipline missing before?

When I came in they were in total shock that Jon had left. But I think the band was at quite a lazy stage in its life as well. It’s funny, I came in for three dates and here I am eighteen years later.

What were those early days like?

I was having a few problems at the beginning, and I remember having a chat to Gillan about it. He said: “Just concentrate on the keyboard, that’s what you should do. Just be the keyboard player.” It was something that Ritchie had said to him: “You just concentrate on the vocals, I’ll concentrate on the guitar.”

Steve Morse says the fans hated him at first. Was it like that for you as well?

A guy would turn up in a Jon Lord T-shirt, and he’d stand in the front row looking very miserable, like Dr Death. It put me off for a minute. But subsequently he started coming to my solo gigs. In a way he apologised to me – he said he hadn’t meant it in that way.

I can’t think of any other band whose fans include Lars Ulrich, former England footballer Rodney Marsh and an ex-Russian President.

We met Dmitry Medvedev for dinner at the Gorky Palace once. We drove through Moscow at a hundred miles an hour, down the wrong side of the road. The American Foreign secretary, Robert Gates, had just had a meeting, so we were following in his path. He used to be an amateur DJ when he was fifteen and he played Deep Purple records. He’d send a list of stuff he was going to play to the Communist Party and then completely ignore it.

What about Vladimir Putin? Is he a Mk III or Mk IV guy?

I imagine he’s not a fan.

The current line-up have been together for eighteen years. What’s the secret?

The older you get, you realise you just want to get out and play to people. All the other ego stuff just gets in the way. I’ve been in a lot of bands where misery was the overwhelming state of mind. With Purple we’ve got a quiet camaraderie. I saw the Stones at Hyde Park. I couldn’t count how many people were up there on stage: two keyboard players, five singers, two extra guitarists. With Purple it’s just the five of us on stage, That’s what it boils down to.

Can you see a point where Purple is no longer part of your life?

It’s something that will happen naturally. But with what’s going on in the world, nobody can see where all this pandemic is going or where it’s going to lead. It might have already happened, who knows?

Roger Glover, bassist with Deep Purple for 39 of their 53 years over two unequal stretches, isn’t unaware of his band’s legacy.

“The word ‘legend’ comes up, which is strange” he says. “It’s hard to live up that adulation. I feel like a normal bloke with a slightly unusual occupation.”

It’s an occupation that has done him well. He’s speaking from his home in Switzerland. Two close friends of his passed away recently, one of which was the producer Rupert Hine, but Glover – the man Steve Morse says is “the first friend you make in Deep Purple” – doesn’t seem in a particularly reflective mood. “It’s sad, but when you get to a certain age you are going to start losing friends. And eventually it’s your turn.”

That’s the album title right there, isn’t it? Whoosh! – everything gone in the blink of an eye.

Time has a way of not stopping, even when you’re stopping. I still find it really hard to believe how old I am. I feel the same as I did when I was twenty. It’s hard to get used to. Of course, the closer you get to the end of your life, you realise what a life you’ve had. Did you waste it? Are you happy with it?

And are you happy with it?

Yes. I’ve been incredibly lucky for a semi-talented dreamer.

There has to be more to it than just luck.

Yeah, but luck is the thing that starts it.

What was the flash-point for you, luck-wise?

Joining a band [Episode Six] at school. Then finding Ian Gillan in 1965 because our singer had left. That was luck, though we didn’t recognise it as luck at the time. Falling into Deep Purple, that was luck. To join a band that was going to have the history we’ve had, that’s unbelievable. It’s like winning the jackpot every day.

Were you intimidated the first time you met Ian Paice, Jon Lord and Ritchie Blackmore?

Totally intimidated. Paicey and Jon and Ritchie were masters of their instruments. We were amateurs by comparison. I went into the studio to play on a session for the song Hallelujah, and we were in different worlds. Paicey was the one who gave the nod to the others that I was an okay bass player. That night, Jon Lord came up to me and said: “We’ve had a little chat and we’d like you to join our band.” I said no.

Really?

Yes. Because we’d been through so much together in Episode Six. I was staying at Ian Gillan’s apartment that night with him and his mother. I didn’t get a wink of sleep. It was a difficult decision to lose my friends, but I realised I’d never have an opportunity to work with musicians like this again.

Did you ever thank Ian Paice for giving you the nod?

No, I haven’t. I only found out about it a couple of years ago. I should. He’s probably forgotten.

The Mk II Purple line-up made all this world-changing music back then in just four years. Does that astound you?

Yes, it does. I used to keep a journal, but I stopped when I joined Purple, so the seventies have disappeared. Apart from what’s in my memory, and that’s become fragmented. But it is an astonishing feeling to write music and have it become a popular band and have people follow you around the world. You couldn’t invent a career like this if you tried.

What was better about being in Deep Purple in 1970 compared to being in Deep Purple now?

Women [laughs]. You’re basically asking me what I enjoyed about being twenty. Being in a big hit band in the seventies, it was every schoolboy’s dream. But it’s all a whirl now.

What’s better about being in Deep Purple now compared to being in Deep Purple in 1970?

[Thinks] I don’t know, really. As things change, some things remain. The attitude towards our music is the same, but you get a different view of things. Certainly songwriting. We don’t write as naïve twenty-year-olds. There’s more of an ease to what we do. We’re not so desperate. But you’re putting something out there for people to judge, so you’re still vulnerable. Even after all this time.

The gaps between albums are getting shorter. Is that urgency due to age, wanting to get as much done while you can?

That would be easy to assume, and maybe it is individually. But to me we have had a career that’s had its hills and valleys. There was a period of struggling before Purpendicular – that album was a wonderful light at the end of a bad tunnel. Then after Rapture Of The Deep we lost the will for doing albums. It wasn’t a good album. I don’t like the sound of it.

All the other guys say Bob Ezrin basically resurrected Purple as a recording band.

Hooking up with Bob and doing Now What!? gave us a whole new feeling of wanting to do things. It was a revelation at the end of our career. A nice way to end.

Is this the end, though? It doesn’t really sound like it.

I don’t want it to end. Or at the very least I don’t want to announce it. We’re in our seventies, things happen to your body that you wish hadn’t. But we’re still in a state where it works for now. As far as I’m concerned, I want to go on doing things until we drop.

Whoosh! is out now via EarMusic. This article originally appeared in Classic Rock issue 278.