It’s December 14, 1981, and Colin Harkness, rhythm guitarist and frontman of Merseyside boogie merchants Spider, is with Dave Hill in Slade’s dressing room at Cardiff’s Sophia Gardens. Like his bandmates, Harkness was weaned on Slade, Eddie & The Hot Rods and Status Quo. For the past fortnight, he’s lived the dream as Spider opened for their heroes on a British tour. In Nottingham, two nights later, Slade’s Jim Lea will grab a bass and join in with Spider’s version of Born To Be Wild.

But right now, Hill is dispensing some advice. Mimicking the super-yob guitarist’s Black Country accent, Harkness recounts it for Classic Rock: “You don’t want to be too much like Status Quo, y’know – focus on the melodies” (in best Cup-A-Soup tradition, that last word is pronounced ‘mel-o-dayyyyz’).

“That guidance stuck with me,” says Harkness 35 years later. “And as time went by we did try to write songs that were more… how can I put it… listenable?”

Regrettably, these efforts went largely unnoticed and Spider were forever tagged as a pauper’s Status Quo. Performing in every nook and cranny of the country, they racked up more than 2,000 shows during a 20-year lifespan. Spider were a peculiarly insular group, contextually speaking, a part of the NWOBHM, but with a style and wit that made them perennial outsiders. They also spurned at least one great rock’n’roll cliché. Staunchly teetotal, Spider consumed 8,000 tea bags while touring with Slade alone, something that later brought an endorsement from the British Tea Council. That said, they replaced alcohol with another vice: women.

Spider’s story is one of alienation, fierce independence and a large dollop of ill fortune. Reviled by the press yet embraced by thousands of loyal fans, they cockily flicked the Vs to any detractors.

Such bravado took Spider to the level of bill-toppers at London’s Hammersmith Odeon. Typically, though, on the day they headlined there in March 1984, the attendance was decimated by a London Underground strike. And two years later, as lorries were due to deliver their third (and final) album to the shops, their record company went into liquidation.

“There’s no such thing as bad luck – you make your own,” shrugs bassist and co-frontman Brian Burrows now. “My belief is that we never really fitted in at all. Most heavy metal bands were riff-based. A thousand bands were copying Judas Priest and Iron Maiden. You can say that we sounded like Quo if you wish to, but there was them and us. We were a rock-a-boogie band, and it became trendy to knock us, especially to the press of that era.”

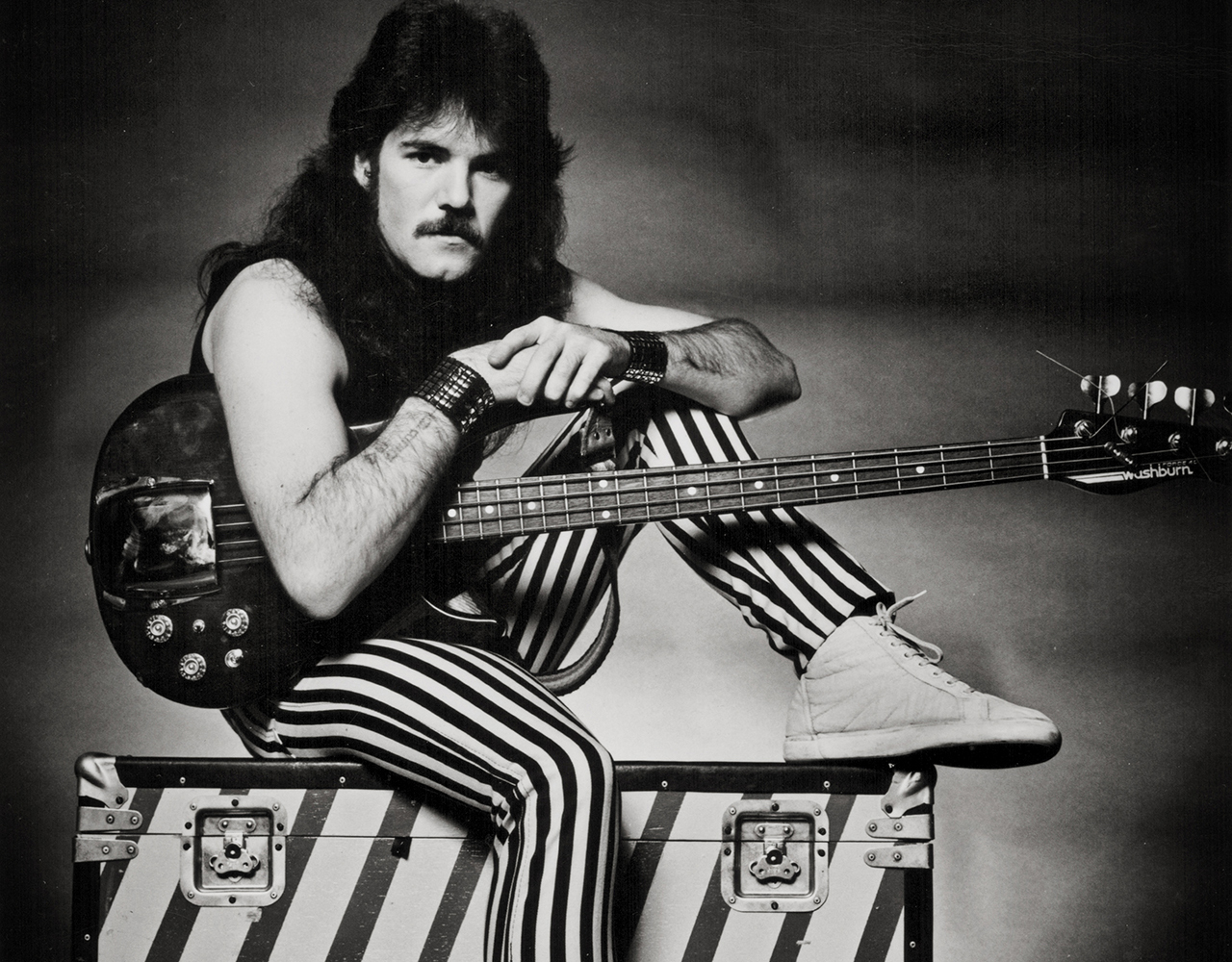

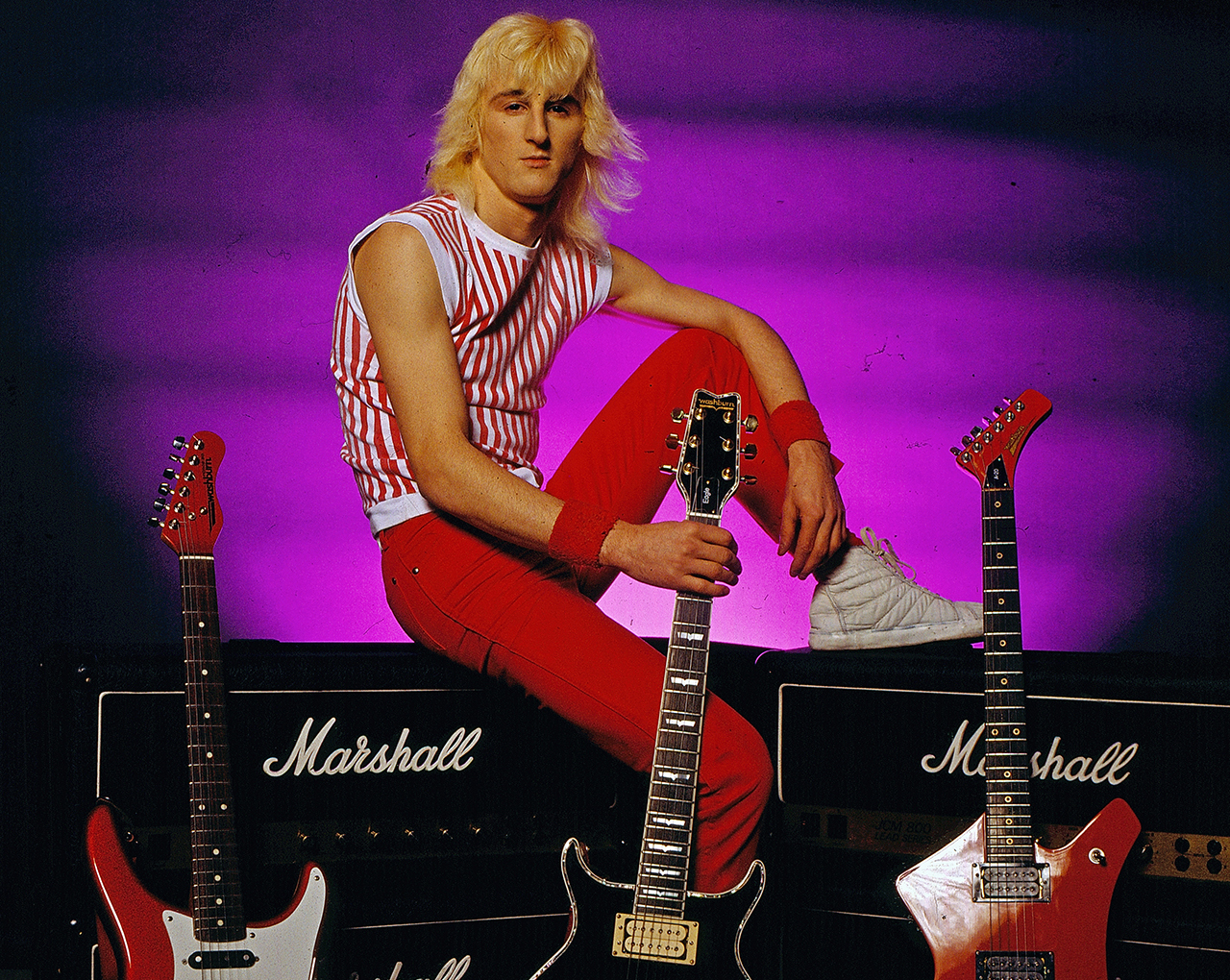

It all began in 1977 when Brian Burrows turned up on Colin Harkness’s doorstep enquiring about a bass guitar he’d heard was for sale. This led to a jam session with guitarist Dave Bryce – nicknamed ‘Sniffa’ for his interest in other people’s girlfriends – and Brian’s younger brother Rob E on drums.

According to Brian, the earliest goal was “just to get the hell out of unemployment-ridden Merseyside”. But before too long, Spider, as they named themselves, got serious. Back then, the band weren’t always hangover-free, and an embarrassed Harkness confesses to “sliding down the microphone, Sniffa running from the stage before he pissed his pants”, at the Grand Hotel in New Brighton. “In the end,” Brian explains, “we decided that alcohol wasn’t big or clever.”

Spider’s web soon spread further afield. Following a show at the Target Club in Reading and having been busted for signing on the dole and gigging, they simply decided not to return home.

Using a shared house in Middlesex as a base, a 35-foot converted coach known as Valhalla (home of the gods) carried Spider everywhere as they developed a raucous stage act that included throwing out sweets and ciggie papers to encourage crowd participation.

In one of their earliest live reviews, Classic Rock writer Malcolm Dome claimed “the quartet’s uncomplicated brand of Quo/Slade stomp-a-boogie went down better than Joan Collins in The Stud”. Each night Brian Burrows would introduce Did Ya Like It Baby? with the words: “This one’s about shagging,” and in 1982, the bassist boasted to Record Mirror: “This band shares everything, including women. If there’s trouble, we say, ‘Last one up is the father.’”

Asked by Record Mirror’s writer whether this was sexist, Brian retorted: “No. The feminists I’ve met aren’t very feminine and all of the women I’ve had have enjoyed it as much as me. I’m pretty good at it, I’ve trained for years.”

Spider are now middle-aged men, some with kids, and the culprit cringes when reminded of such comments: “Jesus! Of course it all sounds creepy now. But isn’t sex a motivation for a young man in any walk of life?”

A nationwide tour in support of Uriah Heep in 1980 was a big step up. It was Heep’s Mick Box who christened them ‘rock’n’roll gypsies’. However, war broke out with the fellow support band Samson after their singer Bruce Bruce (later Dickinson) stuck the boot into Spider’s single, College Luv, as a guest reviewer in a magazine. Things escalated when, following an innocuous exchange of T-shirts, the Liverpudlians covered the backs of their Samson garments with Spider patches.

“If we learned a lot from Heep, we also learned a lot from Samson – how not to be fucking assholes,” Rob E Burrows says with a chuckle.

Following a string of independent singles, RCA Records stepped in to fund their debut album. 1982’s Rock ’N’ Roll Gypsies was simple but effective, though as Harkness now theorises: “We knew it would be impossible to sustain a career by banging out such albums. There’s only so many times you can fit the words ‘rock’n’roll’ into a song title.’” (They had already written two – there would be more.)

At the year’s end, Spider were invited to support Gillan on a whopping 41-date UK tour. This gave them an insider’s view of what proved to be a meltdown in the headliners’ camp, following the news that Ian Gillan was breaking up the band. “We could hear them arguing in their dressing room, and towards the end it became a bit uncomfortable,” Brian Burrows recalls.

Nobody from Spider’s camp recalls the reason why, but there was also a disagreement with Gillan bassist John McCoy following a gig in Southend. “He wrote ‘the bastards’ on the side of our bus – and he spelled it wrong!” Rob E laughs.

However, trouble was brewing at RCA. The label had begun pressuring the band to write hit singles. “When the guy that took us to RCA left the company, our daily contact was the bloke who’d signed Bucks Fizz,” recalls Brian. Spider jumped ship to A&M, but the same thing happened there.

Though Spider had favoured retaining Tony Wilson, producer of Radio 1’s Friday Rock Show and the man behind the desk for Rock ’N’ Roll Gypsies, A&M insisted on using a ‘name’ producer for its successor, 1984’s Rough Justice.

Fresh from producing Y&T’s Mean Streak, Chris Tsangarides encouraged the band to spread their wings. The album began with a judge sternly sentencing them to death for ‘the heinous and dastardly crime’ of ‘playing heavy metal rock’n’roll’. Elsewhere, The Minstrel and Midsummer Morning revealed a hitherto unknown maturity.

“Chris is a good producer, but the timing of our playing was less disciplined than it would have been under Tony [Wilson],” reflects Brian Burrows. “Maybe there was too much experimentation.”

Melody Maker’s Derek Oliver, who’d previously called a Spider live show “hopelessly inadequate”, begrudgingly noted the progress made. However, Rough Justice was awarded one-and-a-half stars (out of five) in Sounds, whose representative, Heavy Metal Heather, dismissed Spider as “about as heavy as a milk bottle top”, suggesting that arachnids should be despatched “with a stiletto heel”.

Bizarrely, Sounds claimed Spider had “greased the stage” for their support act Terraplane (a forerunner of Thunder) during a gig at London’s Lyceum, and although a retraction was printed, the damage was done. The previous summer the band ‘egged’ writers Mark Putterford and Xavier Russell at the 1983 Monsters Of Rock festival, leaving them stinking for the day in the backstage area. Brian claims to have irrefutable proof that the pair played a game of pool during a Spider set in Leeds – a show both writers ‘reviewed’.

“I wouldn’t egg anyone today, but back then it felt like a piss-take,” he sighs. “I’d rather they wrote nothing than pretend they’d seen us.”

The attack caused both sides to become more entrenched. “It became about personalities and not music,” says Harkness, who was innocent of planning the attack. “I wish my name hadn’t been associated with it.”

For four young men who’d never set foot outside the country, opening for UFO on their 1983 European tour was exciting. But it soon became apparent that the headliners were spiralling out of control. In certain territories, Spider were promoted to headliners after UFO vocalist Phil Mogg suffered a ‘nervous breakdown’ in Greece, causing the tour to be abandoned.

“I’ll never forget Moggie telling Neil Carter [of UFO] to say something to the audience in French,” laughs Brian, “but at the time we were in Portugal.”

Meanwhile, back in the UK, the band’s frustration at meagre daytime airplay on Radio 1 boiled over into a song called Here We Go Rock ’N’ Roll (‘Have you heard the latest record/They’re plugging day and night/There’s lots of weird noises/An art student’s delight’). “We’d done our bit by writing these commercial songs, so why weren’t they being pushed by the record labels?” Harkness wonders quizzically. “We might as well not have bothered.”

In what Brian now recognises as a “last throw of the dice”, A&M presented a bought-in song called Breakaway and teamed Spider with a producer, Adrian Baker, who’d worked with the Beach Boys. When it stalled at No.92, the group were doubly devastated as, until last-minute scheduling issues, prior to the Breakaway experiment, Noddy Holder and Jim Lea had agreed to produce a more representative 45. “It was another nail in the coffin,” Rob E surmises.

The notion that Spider were just plain out of luck became more believable still when their new record label, PRT Records, went to the wall on March 10, 1986 – the same day their new album Raise The Banner was due to hit the racks. Though it wouldn’t be officially released until 2012 when their catalogue was revamped, all four members rate the Tony Wilson-produced album as a musical high point.

Behind the scenes, tension was growing as girlfriends entered the equation, and Harkness and Sniffa rebelled against the alcohol ban. The disappointment with PRT was one too many for Sniffa. “I was the quiet bloke who sat around in the background and played the guitar, but I’d had enough of being bossed around by Brian,” he explains. “Without the strain of being cooped up in that house, things might have been different.”

Spider recruited Heretic guitarist Stuart Hurwood for some final shows, though his Edward Van Halen-esque style was a poor fit. “I heard a live recording from the Marquee,” Sniffa winces. “Bloody awful.”

For the remaining originals, splitting up would cause a flood of emotions. “There was sadness, maybe some relief too,” recalls Brian. “After ten years together, things had run their course.”

“It felt like a death,” Harkness admits. “It knocked me sideways and I went off the rails for a bit. I didn’t regain my interest in rock music till about 2003.”

Curiously, none of their members resurfaced in other groups, and with the bassist and drummer moving to France and Australia respectively, a reconnection didn’t take place until this century. Spider played at a fan club gathering in 2015 and were set to dust off the cobwebs for a one‑off gig at the Santa Pod race track in October. However, its cancellation suggests the band’s permanent demise .

Young, carefree and perhaps just a little too cocky for their own good, all four band members recall Spider as the best days of their lives. Ultimately, the cards refused to fall in their favour and in music, just like professional sport, fine margins can separate winners and losers.

“There was some arrogance, sure,” Rob E Burrows admits. “And maybe you had to be in on our sense of humour to get it, but I’ve no regrets.”

So that’s that. Now, we’ll take milk and two sugars please.

NWOBHM legends Spider return for one-off farewell show at Santa Pod