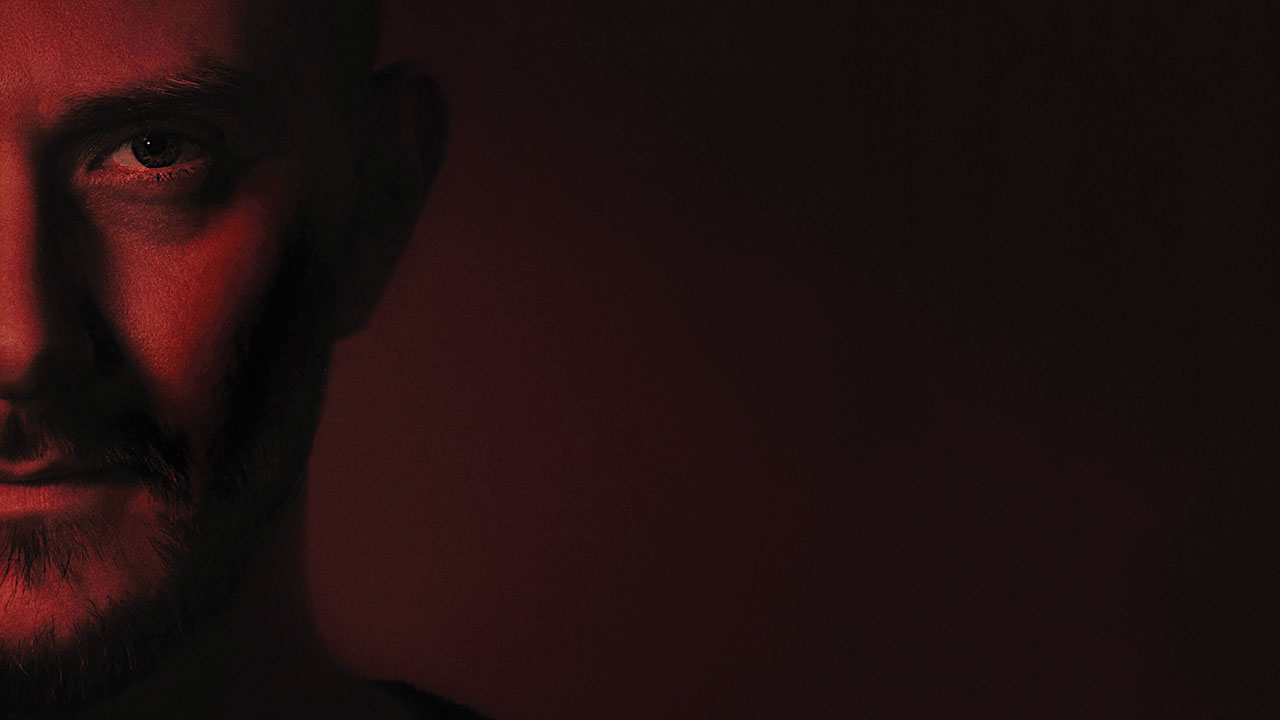

Riverside frontman Mariusz Duda’s fifth release as Lunatic Soul was fuelled by the tragic deaths of a band member and his own father. Prog sat down with Duda in 2017 to find out how the album acted a catharsis for the Polish musician

If prog is to be more than a series of nostalgic glances back at its 70s glory days, it needs artists talented enough to excite and challenge new audiences. No one doubts the defining power of the heroes of yesteryear, but – as the recent chart success of Steven Wilson underlines – prog claims its future by extending the riches of the past.

Mariusz Duda, songwriter and bassist for Polish masters Riverside, is arguably one of those musicians who breaks down walls between genres and finds new riches. Like The Mars Volta or Opeth, he has that tricky knack of seamlessly blending alt-rock, progressive metal and classic prog.

Yet it’s Duda’s solo project Lunatic Soul that provides the Warsaw-based artist with the chemistry to transform his musical DNA. It’s a dismal night in the Polish capital when we catch up with him, but he lights up as he says, “When I created Lunatic Soul I wanted to create something different to Riverside. To create a really original musical world.”

Yet Lunatic Soul’s genesis in 2008 wasn’t the result of frustration with Riverside. Rather, Duda says, “I wanted to make Lunatic Soul something that’s not strictly any genre.”

He admits that perhaps the first four albums didn’t always achieve his aim. With their focus on what he calls oriental sounds, he says, “I sounded like dead-condensed-influence guy, with 80 per cent oriental and folkish sounds and shades of electronic.”

Certainly there are moments on those albums when Duda’s Peter Gabriel and Floydian influences bleed through. Tragedy, however, changes things. On February 21, 2016, Riverside founder and guitarist Piotr Grudzin`ski died suddenly from a cardiac arrest. For the first time, Riverside’s future was decisively and understandably placed in doubt. No one would have dissed the band if they’d decided to stop.

Duda and co responded boldly in 2017 with the Towards The Blue Horizon tour, with Maciej Meller on guitar. It felt like a risk for the band, but, as Duda says, “We decided to prove that we can still carry on and continue our career. It was really nice. People accepted us.”

Grudzin`ski’s death shook the foundations for Riverside, but also had a huge impact on the fifth Lunatic Soul album. Self-deprecatingly, Duda suggests that Lunatic Soul 1-4 sounded too much like music from The Last Of The Mohicans or some historical movie. In the aftermath of tragedy, Lunatic Soul Volume 5, simply called Fractured, was always going to be a different beast.

Fractured’s genesis also involved another heartbreaking event. Grudzin`ski’s untimely death was followed three months later with the death of Duda’s father. “It wasn’t like he was sick for a year – he just died suddenly in an accident,” says Duda, with controlled emotion.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, these challenges brought new dimensions to Lunatic Soul. “Usually I find inspiration in books, films and artists’ weird minds,” Duda says, “whereas this album is mostly inspired by an unexpected turn of events in my life. Mostly it was like therapy for me. The last album [2014’s Walking On A Flashlight Beam] was therapy about loneliness. This album was therapy from personal tragedy."

In this age of spill-your-guts self-revelation, Duda is impressively discrete about the impact of the past year’s emotional trauma. Rather he wants the music to do the talking. “Fortunately,” he says, “I had the chance to be in the studio. I wanted to reflect on everything, but also make something that helps me to move on.”

The most extraordinary shift is indicated by Duda’s choice of sound palette and the conscious effort to fill Fractured with crafted songs. If …Flashlight Beam touched on electronic elements, it still tended – in Duda’s marvellous words – to be “music to dance around the fire to”.

Fractured is a startling departure into the sound textures of Depeche Mode, Talk Talk and electronic-industrial. For fans of Riverside, this may come as a shock. However, as Duda says, “I grew up on that kind of music.”

If the dark, industrial sounds of a Gary Numan-shaped youth are displayed on Fractured, it’s the result of Duda’s bold musical decisions. Peter Gabriel famously instructed Phil Collins to play without cymbals on Peter Gabriel III, and there are similar strategies with Lunatic Soul. The debut album featured no guitars. The key decision this time, Duda says, was to avoid sounds he’d used before. This involved digging into tones as likely to be found on an 80s PPG Wave synth as state-of-the-art keys.

If the musical shifts in Lunatic Soul are beguiling and challenging, Duda recognises he’s in new and risky ground. “I think I crossed some barriers this time. These are brave moves for me.”

Perhaps his deepest fear is of moving away from his instinctive style, which he describes as “very aesthetically pleasing. Not too distorted.”

Certainly Duda’s direction channels the kind of bold steps that have seen Steven Wilson experiment with pop and Anathema’s recent use of dance effects. However, he’s not just interested in innovation for innovation’s sake. One revelation, in particular, is very touching. When talking about Fractured’s most obviously prog track, A Thousand Shards Of Heaven, Duda says, “I composed that on Piotr’s guitar. I bought his guitar because I wanted to have some sort of souvenir from him. When I started to play, all these sounds came up.”

Thousand Shards… is a 12-minute epic, but Duda’s revelation takes it into completely new dimensions.

It’ll be fascinating to see what impact Lunatic Soul’s electronic richness will have on Riverside’s more traditional sound. Will the next album be as much Depeche Mode as Porcupine Tree? Duda says, “I don’t know yet. But whatever we come up with, it will be something very different from Love, Fear And The Time Machine.”

What’s clear is that while there are some wounds that never fully heal – such as the loss of loved ones – people like Mariusz Duda sometimes discover powerful and moving things in the dark. For him, music is the thing. As he says, “When it comes to music the dividing lines don’t matter.”

In the face of personal nightmares, Duda doesn’t lose sight of hope: “I decided,” he says, “to do something less in dark colours but more in red.”