We thought he was immortal but fate dealt the Ace Of Spades man his final hand. JD & Coke in hand, we celebrate his storied career…

As the big screen bursts into life at a little after 11pm, a huge cheer erupts. It’s Saturday, January 9 and Classic Rock is at Big Red, a bar on London’s Holloway Road, for one of several memorial events taking place in the capital for one of rock music’s most loved characters.

Over the next couple of hours we will laugh, cry and whoop in affirmation as a procession of grieving relatives and bandmates, hard-rock superstars, wrestlers, publicists, roadies and people that our subject had met in bars before becoming lifelong friends – even his cobbler, the man responsible for those signature white boots – takes to the lectern to deliver their emotional tales.

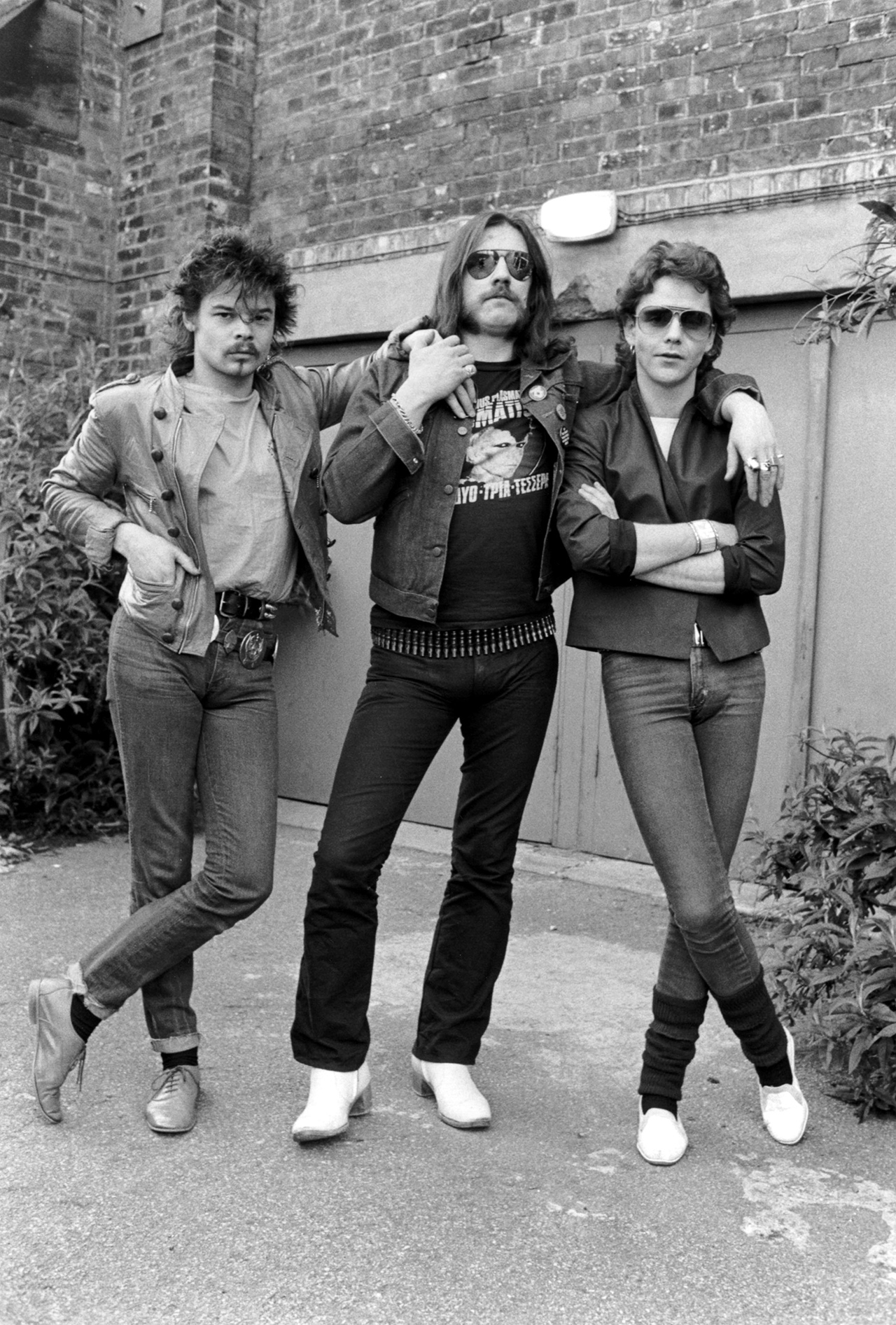

In the background there are immense walls of Marshall stacks, his boots and hat, enough flowers to cover a football pitch. The camera pans in on two black-and-white photographs – the iconic three-man incarnation of his group, Motörhead, and framed above it, the final band line-up that died along with our subject.

Amid a cheering, sometimes weeping, sea of black T-shirts and leather jackets and hairstyles of many denominations, the testimonies from the likes of Dave Grohl, Slash, Scott Ian of Anthrax, Judas Priest’s Rob Halford, Lars Ulrich and Robert Trujillo of Metallica fly by. It’s soon apparent: we will only ever skim the surface of this great and unique man.

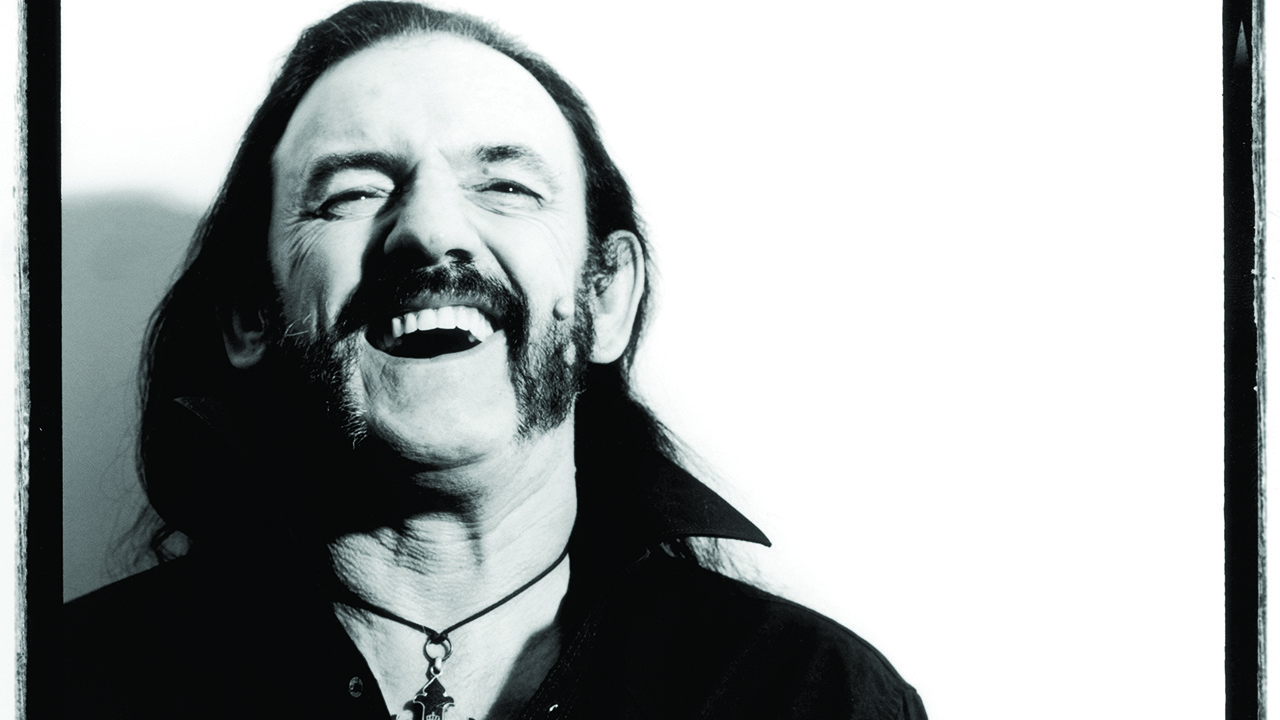

The atheist son of a Royal Air Force chaplain, born in Stoke-on-Trent and raised in Wales but most at home in Hollywood, dry and caustic of wit but with an underbelly far softer than he’d let on, prone to performing at ear-splitting volume but also a lover of books and intelligent conversation, Ian Fraser Kilmister – nobody is completely sure why he is known as Lemmy – was a mass of contradictions. But one thing is for sure. We will never see his like again.

Kilmister had died on December 28, just 48 hours after learning that he had developed an aggressive form of cancer. Several days earlier, on Christmas Eve, his seventieth birthday had been celebrated with a star-studded party and concert at the Whisky A Go Go attended by members past and present of Guns N’ Roses, Metallica, Anthrax, The Cult and many more.

It was common knowledge that Lemmy was ill, but nobody really thought he would die anytime soon. Tour dates for Motörhead were stacked up until the summer when they were due to appear at the Download Festival, following a 40th anniversary tour of the UK with Saxon and Girlschool. But the band’s most recent outings were plagued by cancellations and on occasion they were even forced to curtail their concerts as Lemmy’s breath and stamina deserted him. However, Kilmister never stopped trying, and the fans stayed loyal. After four decades of playing music, he had more than earned their patience.

Kilmister cast an almost omnipresent shadow. It could be claimed that an ability to compose a memorably yet grittily dirty hard-rock song, his hellraising persona, a rapier-sharp wit and take-no-shit plain-speaking made him a living, breathing personification of the rock’n’roll spirit.

After seeing The Beatles at the Cavern in Liverpool, aged 16, he joined The Rainmakers, the Motown Sect and the Rockin’ Vickers. Sharing a flat with Noel Redding in 1967, he found himself working as a roadie for Jimi Hendrix before a relatively short yet incredibly productive tenure with Hawkwind’s classic line-up.

Until he joined Hawkwind in 1971, Kilmister played guitar. The Hawks had to go out and buy him a bass. Despite having joked that he was “a rotten guitarist” Lemmy brought the mindset of six strings to his new weapon, treating it as though it were a lead instrument. But simplicity was always best. When, during the 1980s, a Swedish journalist asked which distortion effect he favoured, Lemmy merely shrugged: “I don’t use no pedal, I just turn the damn thing up.”

“That’s what’s so special about his technique,” said Metallica’s Robert Trujillo before Lemmy’s death. “He also has one of the most unique Marshall amplifiers I’ve ever seen. I’m afraid to turn the thing on… it looks like it’s about to explode. It has wings. So Lemmy’s even thinking about what his amp looks like. That’s craftsmanship.”

When foolishly expelled by Hawkwind four years later for what has been termed ‘pharmaceutical differences’, the bassist famously exacted sweet revenge.

“I came home and fucked all of their old ladies,” he told me in the year 2000. “Not the ugly ones, of course… but at least four of them. I took great pleasure in it. Eat that, you bastards.”

Until talked out of it, Kilmister had famously intended to use ‘Bastard’ as the name of his next band. Their blueprint of deafening volume and fierce musical simplicity inspired Lemmy’s promise: “If we move in next door to you, your lawn will die”. However, long-term prospects of the group that became known as Motörhead didn’t look very rosy.

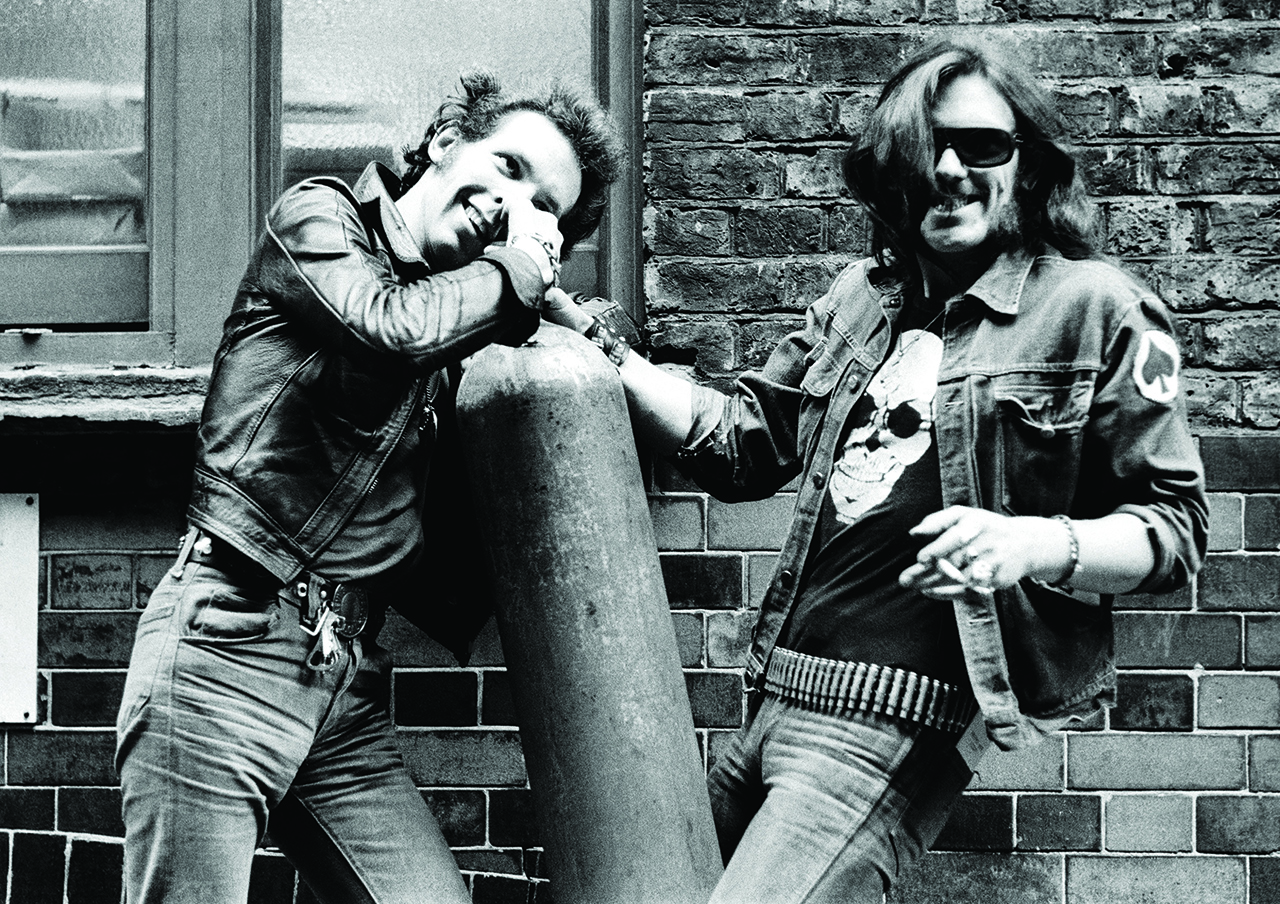

Their best-known early line-up came together more by good fortune than advance planning. With tub-thumper Lucas Fox proving unreliable, Phil ‘Philthy Animal’ Taylor – a former skinhead and football hooligan – snatched the drum stool after giving Lemmy a lift to Rockfield Studios to work with producer Dave Edmunds. ‘Philthy’, in turn, recommended ‘Fast’ Eddie Clarke when they sought a second guitarist alongside Larry Wallis. Unwilling to share the spotlight, Wallis quit and the Three Amigos were born.

Lemmy despised the machinations of the music business. After the band’s first album, On Parole, was shelved by United Artists, only to issue it once Motörhead’s star was in the ascendant, its injustice left him seething.

“The so-called business demonstrates year in, year out that it knows nothing about rock’n’roll,” he once told me. “It’s not even interested in finding out. But I didn’t join the business, I joined the band.”

Talking of which, Motörhead signed to Bronze records despite the fact that owner Gerry Bron called their cover of Louie Louie “about the worst record I’d ever heard”. Bron agreed to release it “purely as a favour” to his booking-agent friend Neil Warnock.

“Gerry Bron might have signed us as a favour but he went on to release five of our albums, so that’s one helluva favour,” Lemmy railed defiantly. “So, again, fuck you!”

Those albums sold in bigger and bigger quantities, but the pinnacle of Motörhead’s success came in June 1981 when No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith – still one of the greatest concert releases ever – entered the UK album chart at No.1. Melody Maker, the same paper that had once called them the worst band in the world, printed a rave review.

“Suddenly, we were the definitive live band, but they were calling us c**ts last week,” Lemmy marvelled.

He also theorised that …Hammersmith “was also our death-knell because you can never follow a live album that goes in at No. 1. What are you gonna do, put out another one?”

Motörhead made unlikely pop stars but those sales figures couldn’t be denied. As their notoriety spread into the mainstream the Daily Mirror clambered aboard the tour bus.

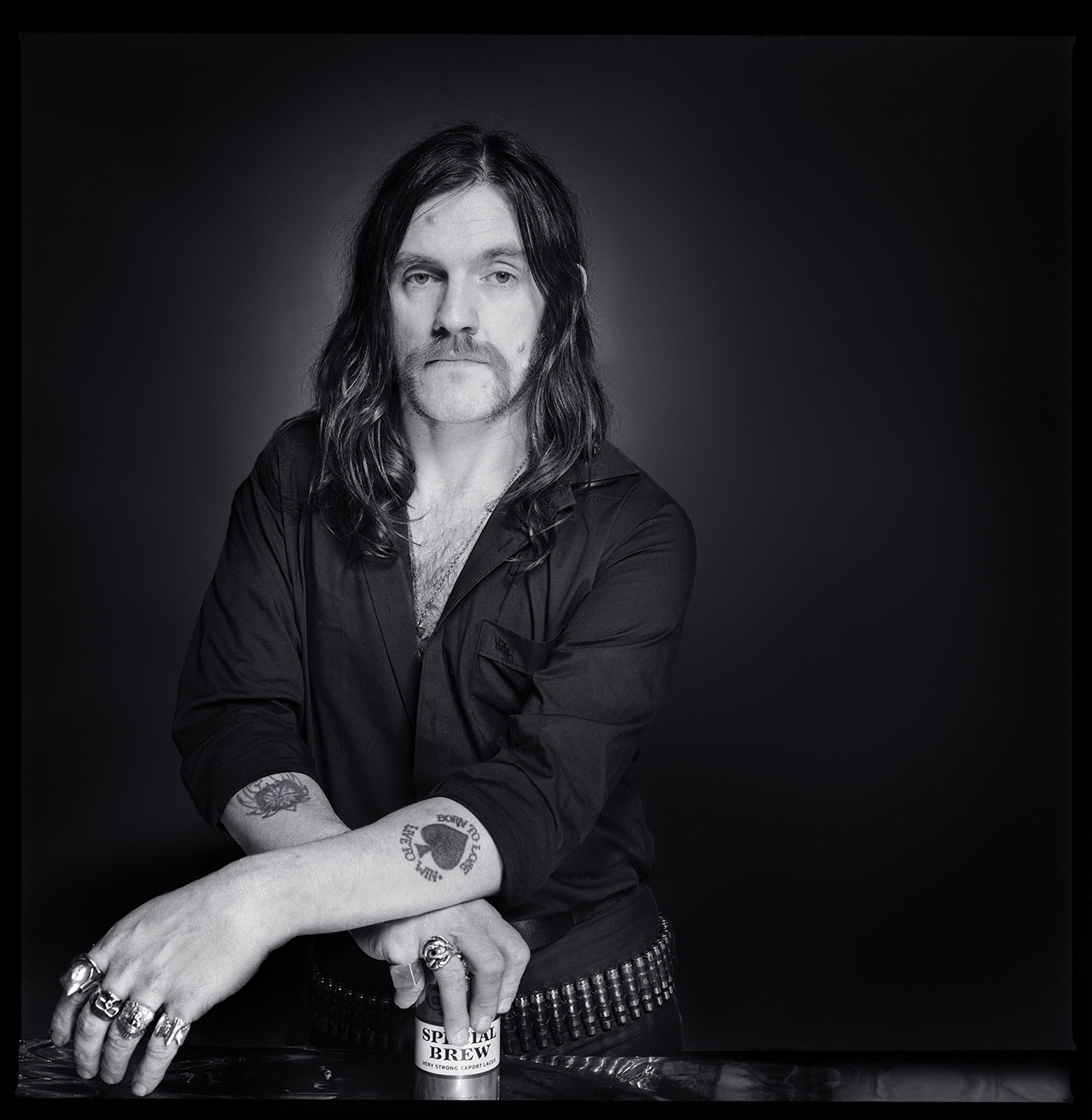

“I drink about two bottles of vodka a day and, of course, a few Carlsberg Special Brews,” Kilmister revealed in a centrespread story entitled ‘On the road with Lemmy, Philthy Animal, Fast Eddie and a bunch of dodgy boilers’. He added: “I’m half-drunk when I go onstage and completely blasted when I come off. I’m in this business because I love rock’n’roll and women. If you can play a guitar then you can pull any chick.”

The Kilmister-Clarke-Taylor line-up would last just one more studio album, 1982’s Iron Fist, before ex-Thin Lizzy guitarist Brian Robertson arrived for the following year’s Another Perfect Day. It was around this time that I first interviewed Lemmy as an anxious journalistic hopeful. Wide-eyed and starstruck, I fouled up by wondering aloud whether the album’s single, I Got Mine, could be a hit.

“Only time will tell, but that’s kind of the point [of releasing it],” he responded patiently, though metaphorically rolling the eyes. It was to be the first of many such interactions, and hopefully the quality of my questions improved. I know that he loved the fact that I named my first born son after him – Eddie Lemmy Selhurst Ling.

When the Robbo-Motörhead alliance turned out a poor fit, Motörhead’s future again appeared bleak. “At one point, just for one day, Motörhead was myself and Phil Taylor,” Kilmister recalled. “And then Phil left, so it was just me.”

As the group’s lone factor of consistency, it’s nothing less than remarkable that Lemmy was able to steer them through four decades of existence, recording 22 studio albums along the way.

“My only real achievement is Motörhead,” he told me five years ago, adding with a self-deprecating smirk: “That and persuading people that I can play the bass, when really it’s touch and go. I cheat a lot, you know.”

Immensely content with the band’s most recent line-up, completed by guitarist Phil Campbell and drummer Mikkey Dee, which ran from 1992 (notwithstanding the exit of guitarist Würzel who left three years later), Lemmy was exasperated by the omnipresence of the Three Amigos.

“I try not to give a fuck,” he insisted. “People can go on about Phil and Eddie all they like, but I know this is the best band I’ve ever been in – no contest. And our latest albums are contemporary because we’re making them now.”

On such form it was always a pleasure to interview Kilmister. Often this would involve taking hits from a trusty bottle of Jack Daniel’s, plumes of cigarette smoke billowing around a hotel room as Lemmy played air guitar and drums, mouthing the lyrics to a new album.

On such an occasion, in 2002, after a preview of Hammered, I enquired how it felt to release Motörhead’s 20th studio album. (Y’see, the questions didn’t always get better.)

“Just the same as number nineteen, only not as recent, and a little ahead of number twenty-one,” he replied, grinning. “It’s an album, y’know, but a good one. It’s fab gear.”

If you really sought to press his buttons, you could try suggesting that a latest album sounded a little familiar.

“It pisses me off when people say, ‘Oh, here’s the usual Motörhead album again’ – we’ve never made the usual one. There’s always something different,” he fumed in response to such an implication. “We experiment, but we do it within our own metre, y’know? And it always sickens that everybody misses it. These people aren’t music reviewers, just hacks.”

Kilmister disliked the term of heavy metal that the media foisted upon him, introducing each live show with the words: “We are Motörhead – we play rock’n’roll.” He had no time for fads. During one of the band’s leaner periods it was proposed that Motörhead might benefit from opening up for masked US nu-metallers Slipknot.

“It’d depend how much [money] they offered, pride wouldn’t get in the way – it’s more about despair,” he responded with a typical mix of bluntness and candour. “I wouldn’t even have them supporting us if it was up to me.

“They’re not a rock band; they’ve got no tunes, no chords or choruses. I just don’t see any redeeming features,” he continued. “Well, maybe one – they’re pretty good at disguises. I came from The Beatles and Little Richard, they come from the circus. Maybe I’m just too old to get it.”

Though he would reassess that viewpoint it was typical Lemmy, aware of his place in the grand scheme of things. “Today’s rock stars are boring,” he told readers of Metal Hammer in 2008. “Most of today’s bands would’ve had rocks thrown at them in the 1970s; they’d have been booed off.”

And yet there was also a slightly vulnerable side if you looked for it. I still recall the corners of his mouth rising slowly after thrusting a piece of paper containing the lyrics to 1916, the title track of Motörhead’s major-label debut of the same name from 1991, under my nose. Sparse and forlorn, mourning the stupidity of war, the track represented something very different for Motörhead, and his wordplay (‘I heard my friend cry, and he sank to his knees/Coughing blood as he screamed for his mother/And I fell by his side, and that’s how we died/Clinging like kids to each other’) was every bit as inspired. And yet affirmation and validation were sought.

The fans loved Lemmy because he was a purist – the guy didn’t even own a computer. Neither did he suffer the presence of fools; those people were eviscerated. With a long memory, you crossed him at your peril. He described his own biological father as “the most grovelling piece of scum on this earth; a weasel of a man with glasses and a bald spot”.

But Lemmy was loyal and intensely honourable. After watching their movie Some Kind Of Monster, the notion of Metallica’s so-called Performance Enhancement Coach, Phil Towle, left him hopping mad. “I wanted to wring his fucking neck. He was just draining their money away. ‘Do you want me to be around a while longer?’ He wouldn’t go ’til their bread was gone. What a c**t.”

During the final months of his life, with concerts and tours being cancelled due to the increasing frailty of his physical vessel, Lemmy found himself torn apart.

“There was a sense of, ‘Thank fuck for that’,” he said in what turned out to be his final interview with Classic Rock (issue 218, January 2016), referring to a completed show in St Louis, Missouri. “It’s bad to let people down. I hate it when it all becomes your fault, you know? Although there’s nothing I can do about it.”

Lemmy just wanted to keep on playing rock’n’roll for as long as possible, and luckily he got that wish.

Like so many males of his generation, Kilmister admitted struggling to address his feelings. He never married, a relationship with Gil Weston, the late former bassist of Girlschool, among his most serious commitments, though he also dated that band’s guitarist Kelly Johnson (who passed away in 2007). At the time of his death he had a live-in girlfriend called Cheryl, who was inconsolable at the memorial.

Perhaps due to his own paternal issues, Lemmy was intensely proud of his musician son, Paul Inder Kilmister, who he didn’t meet until his offspring was six years of age.

“If only for [the fact that] he learned how I feel about him, the film [his autobiographical movie, 49% Motherfucker, 51% Son Of A Bitch] was worthwhile,” Lemmy once told me. “Paul’s a good boy and he plays like a demon, he actually sounds like Hendrix.”

Motörhead entered a rich vein of form with a last half-dozen releases which bore favourable comparison to the ones recorded with the line-up featuring ‘Fast’ Eddie and ‘Philthy’ that the public regard as career-defining, but Kilmister’s health was declining. After having a defibrillator fitted, a spot at Germany’s Wacken Festival was abandoned after a mere six songs, a European tour cancelled. He was forced to give up or moderate most of his favourite things, including Jack Daniel’s and cigarettes.

“In my 25 years with Motörhead I never knew Lemmy to have a cough or a runny nose, and then suddenly three years ago he ran into a wall,” related Mikkey Dee at the funeral.

But still Kilmister refused to give up the road. His last interview with Classic Rock was an uncomfortable, slightly harrowing experience. When I asked whether he could verbalise the sense of frustration he felt, Lemmy fired back a question of his own: “How old are you now, Dave?”

“I’m fifty-two,” I replied.

“Yeah,” he emitted a slightly macabre chuckle, “so you’re still alright. It’s when you get to sixty that things start to go pear-shaped. Everyone thinks that becoming an older guy is easy, but you never consider it fully. It comes as quite a shock. But the thing is, I don’t want to give in to it.”

“We’ll never know how much pain my dad was in because he never complained,” Paul Inder said from the pulpit. “That wasn’t his style.” And yet Lemmy retained his sense of humour, joking about appearing on stage as a ghost after his death in one his final dealings with the media. “I’ll have to stop [performing after I die], I think. You never know… I could haunt somewhere. Mess up somebody else’s gig. Tears For Fears or somebody.”

In those final weeks of HMS Motörhead, the ship had rocked precariously though refused to sink. Sometimes they performed to levels that the group still considered acceptable, and when Phil Campbell was hospitalised for reasons that remain unrevealed, Saxon offered lending their guitarists to keep the tour on track.

“Lemmy didn’t cancel gigs lightly – the show had to go on,” Saxon frontman Biff Byford says. “When Phil was unable to play a couple of shows, Paul [Quinn] and Doug [Scarratt] learned the entire set and were going to step in. They jammed with Motörhead a couple of times. But in the end the band decided to wait for to Phil to come back.”

As he signed off with Classic Rock, Motörhead’s 40th anniversary tour loomed large, its 33-date routing due to take them through 14 different countries. Shortly afterwards, Lemmy appeared at the Classic Rock Awards looking worryingly frail and walking with a cane. He spoke at length to ‘Fast’ Eddie about the decline of ‘Philthy’, who would pass on during that same night. Taylor was just 61 years old.

“It was only a month ago that we buried Phil,” ‘Fast’ Eddie posted on Facebook following Kilmister’s demise. “As the last man standing, the world seems a really empty place right now.” [Clarke declined to be interviewed for this issue, explaining: “I am only just coming to terms with all that has happened.”]

Motörhead manager Todd Singerman says that over the Christmas holidays people had begun to wonder, “Why is Lemmy not talking much? He was slurring really bad.”

At the grave diagnosis that he had no more than six months to live, Singerman believes that Kilmister “took it better than all of us.” Sadly, the end came much quicker than anyone predicted. Lemmy died peacefully at home playing his favourite video game, loaned to him by Hollywood’s Rainbow Bar & Grill.

The tributes flew thick and fast. But besides plaudits from A-listers such as Iron Maiden, Ozzy Osbourne, Metallica, Brian May, Captain Sensible, Dave Mustaine and Judas Priest, everyday anecdotes of generosity carried equal resonance.

Alice In Chains frontman William DuVall told how he had resisted years ago when Lemmy pulled out a couple of $20 bills after he’d provided a ride to a favourite strip club, only for Lemmy to insist: “‘Come on – you’re driving on your spare tyre. Take the money. You need it. This is no time to be proud. I appreciate the lift, and the conversation’. And the truth was I did need it.”

Myke Gray, best known as the guitarist of Skin, related standing outside a snowy North London studio as a freezing cold 15-year-old while waiting to audition for an early band. “Lemmy came out of a door and saw me standing there. Neither of us spoke but he shot me a look that suggested he knew exactly why I was there,” says Gray. “He went back inside, returned and handed me a can of Special Brew, saying: ‘Here, you look like you need a drink’. I will never forget that act of kindness.”

Back in 2010, Lemmy had theorised proudly, “When Motörhead leaves, there will be a hole there that just can’t be filled. That’s fine with me; it means I’ve achieved what I set out to do – which was to make an unforgettable rock’n’roll band.”

More than a quarter of a million people watched Lemmy’s funeral live on YouTube. Since his passing, fans have launched petitions to rename a Jack Daniel’s and Coke as a ‘Lemmy’, also for a newly discovered heavy metal chemical element to be named Lemmium in his honour. At press time, a campaign to send Motörhead’s Ace Of Spades to the top of the UK singles chart resulted in a position of No.13, two places higher than on its first release in 1980. How Lemmy would have felt about these developments is now, regrettably, moot.

At the end of the funeral service, that famous bass was strummed and placed against a Marshall stack next to his urn, feedback filling the room as Singerman concluded: “Lemmy has left the building.”

We really have lost an icon – and an individual – like no other. And we will miss him.