Jon Mikl Thor has one piece of advice for anyone considering inflating a hot water bottle by lung-power alone: don’t.

“Oh, I never want to do it again,” says the professional body builder-turned-cult heavy metal singer of one of the many theatrical highlights of his gigs during the 70s and 80s. “The pain in my lungs. You’re blowing it up and it’s getting bigger and bigger, like a blimp, and you’re holding it with your fingernails to not let the air out, and it doesn’t explode when you want it to. I got knocked unconscious a few times, cos it’s so big it slaps you back… Boom, lights out.”

There’s footage of him blowing up a hot water bottle like a balloon on The Merv Griffin Show in 1976. He races around the stage in tight blue-and-white lycra briefs, golden hair gleaming and muscles aglow, as the in-house orchestra plays the Sweet’s Action! behind him. As he rolls around on the floor with the exertion of inflating up this giant pink blimp, the look on the audience’s faces shift from bemusement to awe. When it finally pops, so do they. “Liberace was on the show too. I walked off the stage and he said, 'Very good Jon,’” says Thor. “I think I looked a lot like his boyfriend.”

That TV appearance was supposed to turn this self-effacing yet determined Canadian into rock’n’roll’s next great superstar: the new Alice Cooper or Kiss. And for a brief moment, it very nearly did. With his Queen, Pantera, at his side, he truly was music’s mightiest hero, the self-professed Metal Avenger with the ripped abs and hot water bottles to prove it. But as much as Jon-Mikl Thor blew and blew, things never quite exploded, and he was shoved in the draw marked “cult curio”: Anvil in a posing pouch.

Yet this isn’t a story of failure so much as a tale of iron will and a heroic refusal to quit. There have been triumphs and heartbreaks, the highest highs and the darkest lows, broken ribs and strokes, retirements and comebacks. Yet Jon Mikl Thor remains standing, battered, bruised yet still dignified.

“Before you’re old and wise, you have to be young and stupid,” he says. “Look at the great conquerors of ancient times. They could conquer great lands, because they were young and innocent and they thought they were immortal. That’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to conquer great lands.”

Back when he was just a young kid named Jon David Mikl growing up in leafy British Columbia in the late 50s and early 60s, Thor wanted to be Superman. His older sister even made a costume for him, which he wore under his school clothes.

“At recess, I would show it the other Grade 4 kids,” he says. “I would change into Superman.” He discovered he wasn’t the Man Of Steel when he climbed onto a first-storey ledge on his school building and jumped off. He woke up with a crowd of kids around him. “I received a concussion,” he says. “Just blanked out.”

There’s still something of the superhero about Thor today. The golden locks and sculpted muscles are long gone, but the 68-year-old has a work ethic that would shame most much younger bands. His latest album, Alliance, features guest appearances from such fellow survivors as ex-WASP guitarist Chris Holmes and former Manowar axe-hero Ross ‘The Boss’ Friedman as well as famous acolytes Danko Jones and Soilwork singer Bjørn Strid. Remarkably, it’s his 20th album since he returned to rock’n’roll in the late 90s after a decade-long hiatus.

“I figure if I make a million records and sell one copy of each, I have a million seller,” he says with a laugh. In truth, the royalties aren’t bad. “We sell enough records and there’s enough demand that we’re doing pretty good.”

The tenacious streak that has kept him doing it in the face of some tough was in place all those years ago when he took a swandive off that school roof. Sure, he couldn’t fly, but there was another way of getting attention: by becoming a strongman.

His big brother was into pumping iron, and the young Thor had already started dabbling with his weights when he was seven. By the time he was 10, he was really getting into it. “I got very strong,” he says. “I didn’t need to wear the Superman costume anymore.”

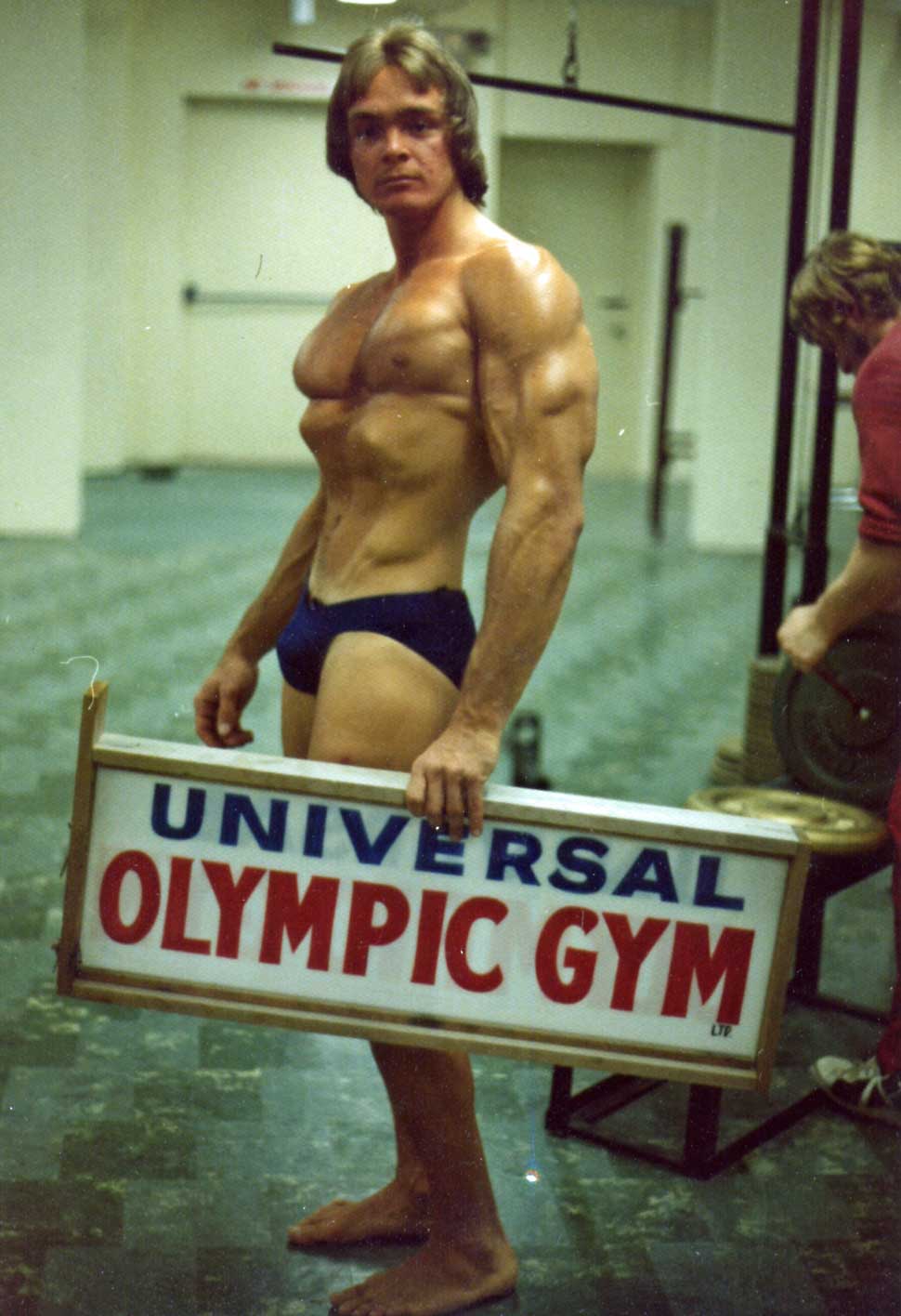

While his schoolfriends were pouring milk on their Cheerios for breakfast, Thor was drinking raw eggs and eating his bodyweight in steak. He entered his first bodybuilding competition at 13; he later went on to win Mr Canada, Mr USA and Mr North America, among other things. Back then it wasn’t the glamorous business it became. If he won a contest, he’d get a trophy and a bag of protein powder. “Now guys get a million dollars,” he says.

In the early 70s, he crossed paths with a statuesque Austrian named Arnold Schwarzenegger, the bodybuilding scene’s new superstar. Thor was due to have his photo taken for a muscle magazine. “I walked in the studio and Arnold saw me and went, ‘[stentorian Schwarzenegger impression] ‘You! Out!’. He didn’t want anybody challenging him. Not that I could - he was beyond the beyond already.”

The quest for physical perfection was tough. “Being constantly criticised for your body – ‘Your calves aren’t big enough!’, or whatever,” he says. “Striving to be more perfect. It’s not easy.” Still, the effort was worth it. Thor won 40 contests during his bodybuilding career. “Forty one actually,” he says proudly. He was a good winner, but a sore loser. If he came second, he would break his runner’s-up trophy. “I was very ambitious. That ambition bled into my music as well.”

Like every kid in North American, Thor saw The Beatles on the Ed Sullivan show in 1964 and thought: “I want to do that.”

He’d started out on the accordion, but gravitated to bass. A string of teenage bands followed: Beatles knock-offs The Ticks, The Cougars, psychedelic rockers Mann (“Two ‘n’s,” he stresses).

When the 60s turned into the 70s and rock heavied up, Thor went with it. “I was bodybuilding and listening to Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath: ‘Wow, these guys drive me crazy, whenever I start listening to them I start really pumping up into a wild frenzy and I go past the pain barrier.’ I thought, ‘This is great, why can’t I meld muscle and music?’”

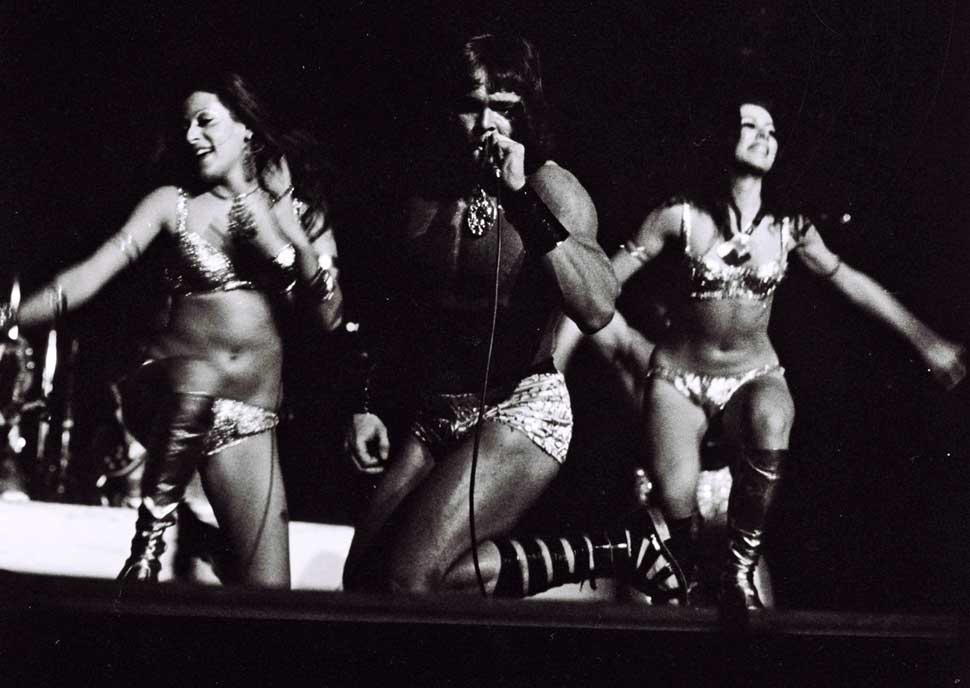

He put together a band, Body Rock, featuring himself plus two musclemen and a pair of Valkyrie-esque female dancers. They matched their music to what he calls “muscle choreography”. Their music was basic caveman proto-metal (sample lyrics: “We are Body Rock… make your knees knock”). Shows found Thor simulating sex onstage with the two dancers.

When that fell apart after one of the women smashed a chair over one of the men‘s heads, he moved to Hawaii to appear in a raunchy, full-frontal musical called What Do You Do With A Naked Waiter?. “You’re getting fondled onstage, you’re getting blow jobs backstage,” he says. “It was wild.”

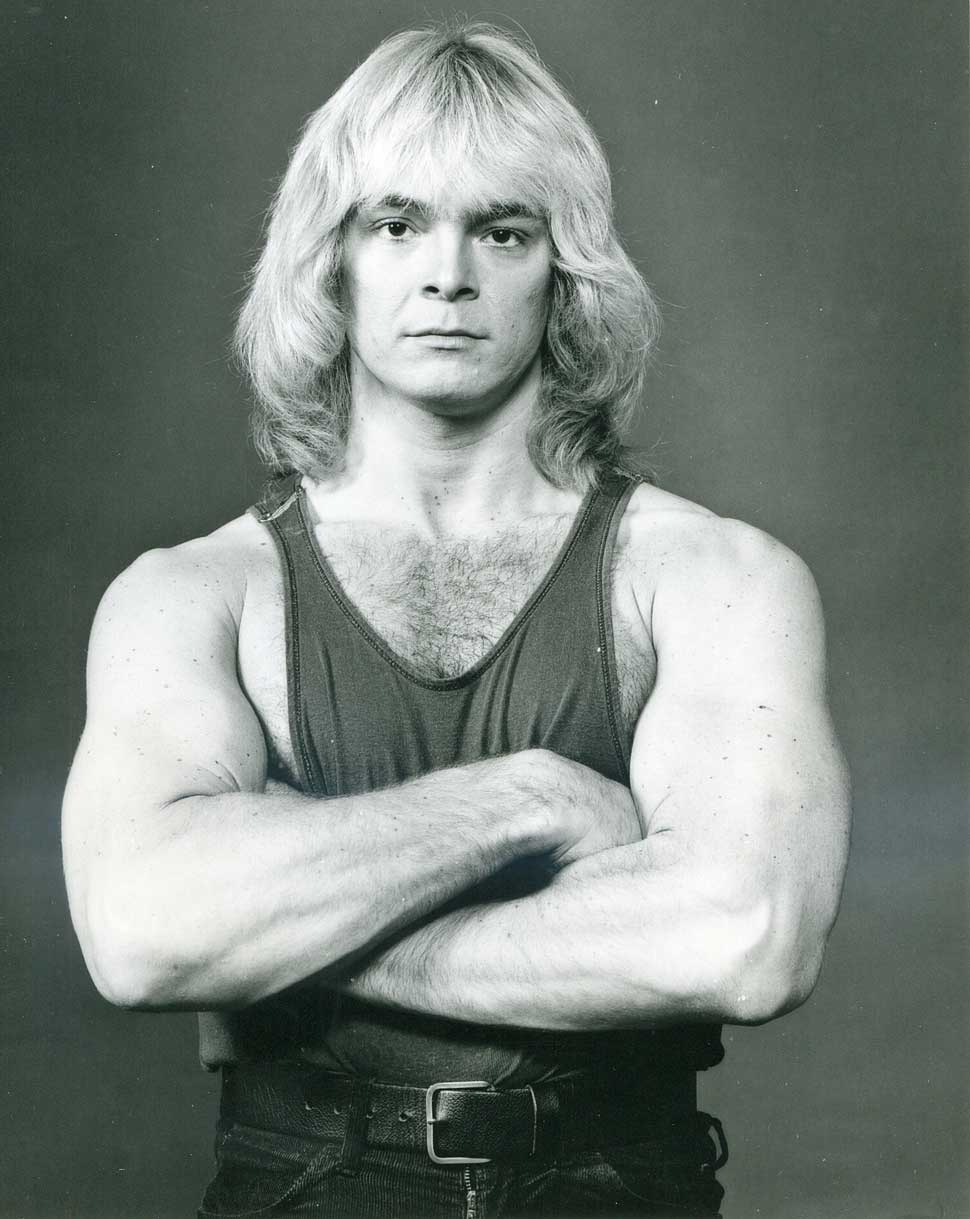

But the lure of rock’n’roll proved too much, and he returned to mainland North America to take another shot at a musical career. He cooked up the Thor concept and the golden god image to go with it. He figured he needed some kind of calling card too, as if being a six-foot muscleman with flowing blond hair wasn’t enough.

A guy he knew taught him the secret of blowing up hot water bottles. Another showed him how to bend railway spikes in his teeth. He hit up some martial artists to teach him how to smash bricks on his chest. ‘I tried all kinds of things to get the crowd going,” he says. “Ripping phone books in two or lifting the heaviest person up in the audience with my neck.”

Audiences were either impressed or determined to prove they could out-Thor Thor. In one rough-arsed bar in Quebec, a guy came onstage bragging he could bend a steel bar in his mouth too. “But he didn’t put the cloth around the steel, so he broke his teeth and went crazy,” says Thor. “There were always guys trying to fight me. I was, like, ‘Hey, I’m just trying to put on a show for you people.’”

Most of the damage was suffered by Thor himself in the name of showbiz. He used to invite audience members onstage to swing a sledgehammer at the bricks balanced on his chest. “One night there were no more bricks left but the guy kept swinging the sledgehammer. Busted my ribs. I’ve broken ’em many times.”

He suddenly sounds sad. “I always ask myself, we had the costumes, we had the talents, did I really need to do all the strength feats? Doing them for real, where I injured myself? Was it necessary to do all that?”

Apparently it was. The first half of the 70s was a golden time for theatrical rock’n’roll. Alice Cooper was king and Kiss were the pansticked demon dogs biting at his heels. Thor’s showmanship fitted in perfectly with rock’s larger-than-life new gods.

He began to make a name for himself in Canada and down the East Coast of the USA. One person who was impressed by his show was a young Irish exchange student named Robert Geldof, who gave it a glowing review in a Canadian newspaper. Not long after, Geldof returned to Ireland, shortened his name to Bob and formed The Boomtown Rats.

By 1976, Thor had recruited a backing band he named The Imps. “Because the other guys were short,” he says. I used to pick the guitarist up and throw him around and out into the audience while he was still playing,” he says.

Thor And The Imps recorded an independent album, Muscle Rock, which got Thor noticed by the producers of a Bicentennial Vegas show, Red Hot And Blue. He signed up to perform as the great American heroes: Paul Revere, Elvis Presley, his old idol Superman. He would fly over the audience on a cable that could hoist a two-ton truck. One time the cable snapped as he was approaching the stage. “It almost killed me. It could have finished my career right then,” he says, flinching at the memory.

Thor’s Vegas wasn’t the Vegas of Frank Sinatra and Elvis. He was hanging out with The Osmonds and Rodney Dangerfield. “I get no respect, no respect at all,” he says, launching into a spot-on impression of the perpetually rumpled comedian. “We’d have parties and all those guys would come along.”

He loved Vegas, but it wasn’t him. He wanted to rock’n’roll. The Merv Griffin Show – filmed at glitzy casino-come-hotel Caesar’s Palace – gave him a leg up, put this blond bag of muscles with his crazy hot water bottle antics in front of a massive TV audience. That in turn attracted the attention of RCA Records, who shoved him in a studio to record an album, Keep The Dogs Away.

That record, released 1977, is a near-perfect hit of beefy 70s glam-metal. RCA were ready to throw their weight behind it. Thor was all set to become the next Kiss. Except…

“It all went kaplooey,” says Thor. “Some weird malarkey happened and it left me out in the cold.”

This is where the story gets murky. In Thor’s telling, a “huge” tour had been booked – 5000-seater arenas – only to be mysteriously pulled without his knowledge. “Someone told promoters, ‘That’s not gonna fly, who’s gonna come and see this guy who doesn't have any hit songs?’”

It’s hard to get to the bottom of exactly what happened. There seems to have been a battle between his label and management company. Bruce Springsteen’s former manager, Mike Appel, was somehow involved. “He told the label he could do a better job than the current manager I had,” says Thor. “People pointing fingers at each other.”

At one point, Thor claims he was kidnapped at gunpoint by shadowy assailants. He won’t go into specifics, and it’s the only time his tone darkens. “That’s one thing I can’t talk about,” he says. “It was a horrible time.”

Whatever the truth, the upshot was that Keep The Dogs Away withered and died on the vine. Thor took it badly. “I was injured, mentally and emotionally,” he says. “It was a tough time. Sometimes I think I should just have walked away and become a doctor or something.” Only he didn’t. He did what he’d always done. He waited until the hurt stopped, picked himself up and got on with the business of being Thor.

By his own admission, the next few years were tough for Thor. He tried to stage the Keep The Dogs Away tour himself, but it was “a shambles.” The rock’n’roll dream was slipping away.

Luckily, he had a great support system. Rusty Hamilton was a journalist, model and costume-maker. The two had met a couple of years earlier at one of Thor’s gigs, and swiftly became an item. The pair were well-matched in terms of drive and ambition, and Rusty began helping Thor get his career back on track (she would later become the band’s backing singer and onstage performer, Queen Pantera).

Even then it wasn’t easy. There were false starts with Kiss manager Bill Aucoin and, weirdly, Mike Appel (the latter relationship reportedly fell apart due to Appel’s habit of taking advice from a demon, Seth). But Thor and Rusty had elevated tenacity into an Olympic sport, and they weren’t about to give up now. It was a great partnership. “At that time, yeah,” says Thor wryly.

It was 1983’s Unchained EP that finally gave him the break he needed. It featured the stone-cold classic early 80s metal Anger, accompanied by an unintentionally hilarious no-budget promo for the latter featuring Thor as a heroic barbarian figure rescuing a damsel, played by Rusty, from a ruined castle in New Jersey. It was posted on YouTube a few years ago by the man who produced it, under the heading “The Worst Video Ever Made”, which isn’t entirely inaccurate. “Hey, it got a lot of play in New Jersey,” says Thor, self-deprecatingly.

Still, Unchained grabbed the attention of Motorhead manager Doug Smith, who bought Thor to the UK. He was embraced by the music press, who gave him the larger-than-life treatment he deserved. When he played the Marquee club in 1984, Jimmy Page was in the crowd. The teenage muscleman in him who had span into a wild frenzy while pumping iron to Led Zeppelin was blown away.

“He was at the aftershow, in the corner,” says Thor of Page. “I went up to him and said, ‘Hey, how’d you like the show?’ And he just fell asleep. I never got an answer.” He smiles wryly. “I guess he’d had a few too many.”

There were friends who did manage to stay awake in his presence. Ozzy Osbourne was one. Lemmy was another, as was Hawkwind’s Nik Turner. “I think those guys were amused by me,” he says. “They liked the fact that I was theatrical.”

He wasn’t the only well-oiled man in a loincloth on the 80s metal scene. But where peers such as Manowar were taking themselves very seriously, Thor at least had a grasp on the ridiculousness of what he was doing. “Joey DeMaio said, ‘I’ll die for metal,’” says Thor of the Manowar bassist, rolling his eyes. “Come on, I’m not gonna die for it.” He laughs. “Well, maybe the hot water bottle could’ve killed me.”

Another album, 1985’s Only The Strong – featuring two more killer anthems, Thunder On The Tundra and Let The Blood Run Red – sealed his position as heavy metal’s mightiest avenger. He even made a memorable, if bizarre appearance on British kids’ TV show, No. 73.

But Thor was ambitious. He’d wanted to be an actor ever since he saw strongman Steve Reeves in the 1958 movie Hercules, and had even appeared in the 1972 movie Ground Star Conspiracy alongside future A-Team star George Peppard. By the mid-80s, he decided to put the band on the back burner and take a crack at big screen stardom.

Thor says he had a blast making movies with titles such as Rock’N’Roll Nightmare and Zombie Nightmare, but his career didn’t give Sylvester Stallone or his old nemesis Arnold Schwarzenegger any sleepless nights.

Worse, the cumulative pressure of more than 20 years of non-stop hard work – first as a bodybuilder, then as a musician, now as an actor – was beginning to take its toll. His mental health started to take a serious nosedive. He started hearing voices and seeing things that weren’t there. He found himself walking around New York at all hours, living a vampire-like existence.

“Sometimes things can get very dark,” he says. “When things go wrong, it feels like there’s a cloud over your head and water in your brain and there’s no hope.”

Things did indeed get very bad. Thor became severely depressed. His nadir came when tried to hang himself from a shower rail. The only reason he didn’t succeed was because the rail gave way under his bulk.

“I was on my back for a while,” he says of his life in general at that point. “But there’s always hope, there’s always a chance for things to get better. If you see a little bit of light coming through the clouds, just grab it. I grabbed that ray and the clouds just started opening up.”

In 1987, Thor decided to retire from music, from movies, from public life. He returned to Canada and had what he called “a total nervous breakdown”. He relocated to North Carolina to recover and put clear water between him and his past. “I started walking in the woods, not thinking about showbusiness,” he says. “Slowly, I started getting better and better.”

He took a job working for a glassware company, which he eventually bought with the royalties he’d made from his records and movies. It was the era of the microwave oven. “Suddenly everyone bought microwaves that Christmas,” he says. “So we started making microwaveable products.”

The microwaveable products business was booming, the royalties were still trickling in. He built his own house and carried on walking in the woods. Life was good for Thor.

“And then,” he says. “I made the mistake of getting back into showbusiness.”

In 1998, Thor released his first studio album in 13 years, Thunderstruck: Tales From The Equinox. He’d started a label a couple of years earlier, but the bands he signed weren’t doing the business, so he figured if you want a job doing properly, do it yourself.

The excellent 2016 documentary I Am Thor charts his comeback. The interim years had reduced Thor to a footnote at best and an outright joke at worst – a ridiculous muscle-headed buffoon who blew up water bottles on stage. The film shows him playing tiny clubs and backrooms to sparse audience of fans who were there for the kitsch value of seeing a vaguely camp 80s heavy metal star in reduced circumstances.

Yet it also paints a portrait of a funny, humble man whose apparent lack of showbiz ego is in inverse proportion to his desire to entertain. There are illuminating details, such as the fact that he created a fictitious alter ego, Steve Scott, to manage himself – partly the result of being burnt by previous real-life managers and partly the result of the stubborn focus that at one time led him to a nervous breakdown. Most touchingly, it highlighted an intense love for him from a small but ardent core of fans who recognised and admired his dedication, his unwillingness to quit and, naturally, his music.

Not that his return to rock’n’roll has been a smooth ride. His marriage to Rusty fell apart in the late 1990s, partly a result of his return to music. He suffered a stroke in 2007 which left him temporarily blind in one eye. “Ah, I’m fine now,” he says cheerfully, as if he’d just caught a sniffle. “I had a friend recently who passed away, same age 68. He was a superstar at school, he was the soccer hero, he was the baseball hero, he was everything, You see how mortal we are. I say embrace life.”

Thor is still doing that today. He recently shot a video for the single, Because We Are Strong, featuring his old friend Lou Ferrigno, aka the original Incredible Hulk. And he’s just filmed a full-length movie, Pact Of Vengeance, in which he plays an army general who “supplies all the ammunition for the madness.” He laughs when the subject of the other Thor – aka Chris Hemsworth – comes up. “We co-exist. I know he’s there, they know I’m here. Who knows, one of these days, those two worlds may collide.”

Yet for all that, Thor’s a realist. Just as he realised he wasn’t superman when he jumped off a school roof in fourth grade, so he knows that he’s not the indestructible, carved-from-granite man-god he once was. He thinks a lot about not having the pressure of being on rock’n’roll’s frontline. “The last album is strong enough that I could maybe close the book on it,” he says. “Maybe Keep The Dogs Away and Alliance are the bookends on my career.”

If it does all end tomorrow, there’d be few regrets for Thor. Not the missed chances or the failed relationships or even the broken ribs.

“I thought I was going to be bigger than The Beatles,” he says. “That didn’t happen. I never became as big as Ozzy, or as so many others. But I’m satisfied with my stature. I have a beautiful life. All the sacrifices, all the pain, all the battles… I’ve come through them and survived."

Thor's new album, Alliance, is out now via Cleopatra Records.