On a cold and rainy morning, the five members of Thunder are gathered at the place in South London where it all began. The place where singer Danny Bowes and guitarist Luke Morley first met and became friends more than 40 years ago.

Haberdashers’ Aske’s Hatcham College was a traditional grammar school in 1971, the year in which Bowes and Morley started their first term at the age of 11. It’s an appropriate place for a photo shoot, given the title track of Thunder’s new album, Wonder Days, is a hymn to their youth, its lyrics filled with memories of the school and the rites of passage in their formative years.

As they walk around the college, there’s no dewy-eyed nostalgia. “I couldn’t wait to get out of this place when I was a kid,” says Bowes. But what developed here, the relationship between him and Morley, has defined much of their lives since, with the bands Nuthin’ Fancy and Terraplane in the 80s and then with Thunder for the best part of 26 years.

Wonder Days is Thunder’s comeback album, their first since the band split for the second time, in 2009. Bowes quit for an alternative career in the music industry and Morley formed a new group, The Union. But in the ensuing years, Thunder never disappeared completely. The band continued to operate on a part-time basis, playing annual Christmas gigs and occasional tours. But with this new album they’re making a statement. “We’re back,” Bowes says. “It’s that simple.”

During the making of the album came the biggest crisis of the band’s career, as Ben Matthews, their second guitarist and keyboard player, underwent treatment for cancer. Thankfully, Matthews has since made a full recovery. And it’s something he’s more than happy to talk about.

Photo session over, drummer Harry James and bassist Chris Childs head home. Matthews, Bowes and Morley head to a restaurant where they eat together before being interviewed separately.

Bowes chooses to go first. He likes to talk and has a businesslike air in keeping with his additional role as Thunder’s co-manager. In fact, it was the pressure of working double duty that led him to leave the band in 2009. But, as he will explain, things are a little different this time around.

With this new album, does it feel like a new beginning for Thunder?

Well, having announced in 2009 that we wouldn’t make another record, I’m not massively into making predictions any more. But we’re not intending to put the record out, tour and then split up again. This had to be proper commitment. And we needed to make sure we weren’t going to make the same mistakes as before.

Meaning what?

I still manage the band, but I’ve got help. Plus we’re signed to a label now, instead of running our own. For seven years I was managing the band, running the label, taking care of all our business. Be careful what you wish for. You want to be in charge of your own destiny, but it was a hard job – too hard.

And that’s why you quit the band in 2009?

I was burnt out. I’d been working seventeen, eighteen hours a day, and I was hanging on by the skin of my teeth. I was nearly fifty and thinking, “Can I go on like this without having a heart attack?” I was genuinely concerned about that.

_ _

Were you also concerned that you were no longer making enough money out of the band?

That was a factor. We always sold loads of tickets, but the business was contracting. So I sat the band down and said: “I think we should stop.” I’ll be absolutely honest, it was my decision.

How did the other guys take the news?

They weren’t happy. But I did what I had to do. The lifestyle conversations I was having with myself were not going well. I wasn’t getting any younger. My kids’ university fees were coming up. And then our booking agent said: “Why don’t you come and work with me?” It was very attractive: a day job, regular money. I ended up doing that for two years.

In recent years, have you done any kind of work outside of the music business?

I was a carpet fitter after leaving school. My old man had a carpet business so I worked for him. Even now I still do a few jobs every now and again.

When was the last time you laid a carpet?

September. It’s good, honest graft.

You’re a proper working-class boy. Is that what defined your personality?

I’m from a council estate in Eltham. I come from a big family and we used to row all the time. So I’m fiery. I’ll have a row with anybody, all day long.

How did you end up at that posh grammar school?

My teacher at junior school put me up for selection. You had to be the top ten per cent of intelligence in this country. And from the start we were told: “You’re very lucky to be here.” The pressure to get good grades was unbelievable. I hated it.

But it was there that you met Luke.

It’s funny, because Luke’s temperament was not at all like mine. Luke would run a hundred miles rather than have a row. It suits him to let me have the rows. We were very fortunate in recognising each other’s qualities early on. I’m a doer. I’m the son of a retailer, so I was always interested in how the money got made. But I realised very quickly that I wasn’t very creative when it came to music, whereas that’s all he cared about.

What has made this relationship work for so long?

The respect we have for each other. When we were making our third album, in America, my wife was eight months pregnant and she called me, saying: “I need you to come home.” When I told Luke, he just said: “Go. Don’t worry about the album. We’ll work it out later.” That meant a lot to me.

Before you met your wife, were you a bit of a swordsman?

It would be very dishonest to say that none of those shenanigans happened. When you’re a singer in a band you can be choosy. But I never felt the need to get those notches on the bedpost. I met my wife in 1989, the same year we made the first Thunder album. And by that time I was ready to make a commitment.

Have you done a lot of boozing and drug taking over the years?

When I was nineteen I was drinking every night and fitting carpets. I got backache. After my doctor did some tests, he showed me pictures of two livers. One was lovely and bright and shiny, the other was green and like a sponge. And the doc said: “Yours is well on the way to looking like that.” That scared the living daylights out of me.

But you didn’t stop drinking.

No. In a band there’s booze all around you. I thought: “How am I going to survive this?” So I reasoned that if I drank every other day, I’d be okay.

And drugs?

This is the absolute truth: I’ve never been offered drugs. Not ever, in my life.

You never wanted to use drugs in the creative process, like so many great artists did?

It never occurred to me that you needed to get into an altered state in order to make a record. I never enjoyed singing drunk. And this was something that Terraplane’s manager instilled in me: when you get in front of an audience, don’t fuck up – be great. And as I get older, it becomes more and more important that when I do my gig it’s good.

Why?

Because I feel like I’m running out of time to do good work. I’m very aware of the fact that any time I make a record or do a gig, I want to make it part of my legacy. I want people to remember me for being good.

If Danny Bowes is the brains in Thunder, then Luke Morley is the heart and soul of the band. He’s the principal songwriter, and it was Morley’s desire to make a new album that has resulted in this full-scale comeback. He’s less intense than Bowes, and when he talks about Thunder, it’s all music, never business. Only now, after what Ben Matthews has been through, Morley has an even deeper appreciation of the band and the people in it. “I enjoyed making this album,” he says. “But the biggest difference was not having Benny around while we were recording. You miss the banter.”

The last year has been a tough one for the band.

It has. When Benny got ill, it knocked all of us sideways. Up until that point I don’t think any of us had noticed how old we were [laughs]. It comes from being in a band. Playing music is something you start as a teenager, and part of you is still that kid, even in your fifties. If you do this for a living, a part of you has to be that permanent teenager.

You’ve written about your teenage years, and your old school, on the new album’s title track. Did you and Danny hit it off instantly?

Not straight away. Halfway through the second year, around thirteen, we started to get to know each other and move in the same social group.

Were you a working-class kid like him?

My roots are extremely working class. My grandfather was an Irish chimney sweep who did a bit of boxing. But my parents gravitated towards a more middle-class existence, I guess. Both my folks were art teachers. The house was full of books and paintings, that kind of atmosphere. Danny’s folks were more working class in the traditional sense.

Was your friendship rooted in music?

Not at the start. I was playing guitar from the age of eleven, but apart from him liking the same music as me – Bowie, Zeppelin, the Stones – I didn’t think he was in any way musical, until he said: “I can sing.”

What has made this relationship work for so long?

We’ve got a lot of common ground – life experience, where we grew up. It’s a mixture of that and the fact that we’re good at different things. Danny is pragmatic, an organiser – a ducks-in-a-row kind of bloke. I’m more creative, more artistic.

You write the songs. Danny co-manages the band. Which one of you is the boss?

Neither. But I’m definitely a control freak about the music, and the others are happy to do as I say.

Is ‘love’ too strong a word for how you feel about Danny?

Ha ha ha!

I’m serious.

Well, yeah. I’d say the same about all the boys.

But that love must have been tested when Danny walked out on the band six years ago.

Honestly, no. Danny wanted to try a new career and I said, “Fair enough.” We’ve always had that attitude that if you want to do something, you do it.

Did you ever consider doing something other than making music?

Never. That’s what I do – I write songs and go out and play them. That’s my life, very simply.

Have you ever felt that you’ve missed out on other things? Danny had children, but you never did.

In those early years of Thunder, when Danny was having kids, I was completely wrapped up in the band. He would come in and do a job and go home, while I would be working on a record. But really, I think if I’d needed to do it, having kids, I would have done.

Ever thought about kids when you got married?

I think if she’d got pregnant at some point we’d have gone ahead with it. But it didn’t happen. And she’s got a great career as well, so one of us would have had to sacrifice a lot. And now, really, we’re too old.

When did you get married?

Hmmm… better get this right or I’m dead.

Would it be easier if I asked you when Led Zeppelin released Physical Graffiti?

Yeah. That was seventy-five. But I got married in 2011. Phew!

You’ve written so many of the band’s songs. In terms of lyrics, which of your songs reveals the most about your own life?

A Better Man is very personal. In fact, the whole of Laughing On Judgement Day [1992] was written about the two sides of a relationship I’d been in. All of the songs are about either being in love with this person or wanting to strangle them!

Is there a song on the new album that relates to Ben and what he’s been through?

Yes. A song called Resurrection Day. I wrote the melody before he got ill. And then, during his treatment, I wrote the lyrics. They’re not direct, I didn’t want to make the song too cheesy, but it’s about him, about getting through dark days.

When he was first diagnosed with cancer, you must have feared the worst.

Well, in 2011 I lost two close mates, both of them younger than me. One was cancer, the other one just dropped dead for no apparent reason. And around the same time my wife’s best friend also died from cancer. Between diagnosis and her dying was fourteen months. She was only thirty-six.

What could you do to help Ben?

Realistically there’s nothing you can do. That was the hardest thing for the rest of us. But we were all trying to be positive about it, and so was he. I read loads about it online. I learnt that the recovery rate for this type of cancer is really good, but also that the treatment is one of the worst. They take you about as close to death as they can take you – right to the edge. My biggest concern was his mental strength – can the poor sod cope? In that situation, a lot of people give up.

How did he cope on that psychological level?

At first he made jokes about it. “Oh, I’d love to make a cup of tea but I’ve got cancer.” But you get to a point when you realise that you don’t have to put on a brave face because everybody knows what you’re going through.

When did you realise that he was going to be okay?

I went to see him one day. He was so thin and could hardly move. Bits of his hair were hanging off. All he could do was try to stay awake while I was there with him. But in the hour I spent chatting to him, I could sense that he was getting better.

A great moment.

It was fantastic. You know, he was in a lot of pain for a long time. But he got through it.

Ben Matthews is slimmer than he used to be. His greying hair is a little thinner, and cut shorter. Other than that, there are no outward signs that he has just endured the ordeal of chemo and radiotherapy. There are a few things he can’t do now. Eating couscous is one: “It makes me choke,” he says. He wasn’t able to play guitar on Thunder’s new album, but he is ready for the band’s UK tour in March.

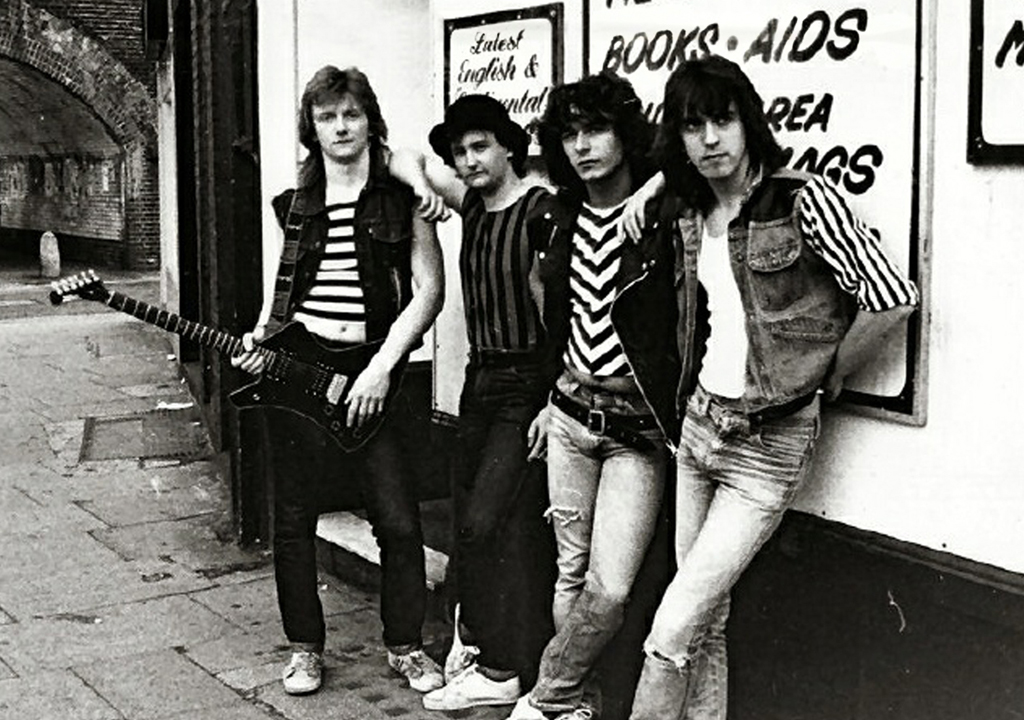

At fifty-one, Matthews is three years younger than Danny Bowes and Luke Morley. He has known them since he was 16, when his band White Noize and their band Nuthin’ Fancy played in the same pub, the White Swan in Blackheath. Subsequently, Matthews became one of the founding members of Thunder when they formed in 1989. “I feel so lucky to be in this band,” he says. “I love the music, and I love the boys in the band. Now more than ever.”

After all that’s happened in the past year, how are you feeling now?

I’m doing great. I’ve had the all-clear. There are some annoying side effects left over from the treatment – I’ve got hearing loss, and that could last another year or so. But, you know, it could have been worse.

No shit.

Ha ha! Well, it’s true. And I’ve got piece of advice for anybody who’s getting old: whenever you have a niggly problem, get it checked out.

Was that how your cancer was discovered?

Yes. For a couple of months I had a mild earache and a sore throat, so I saw my GP. And fortunately for me she’s a specialist in an Ear, Nose and Throat Department in Lewisham. She was feeling my neck and said: “I don’t think it’s cancer.” I said: “That’s good!” So I went into hospital to have my tonsils removed. But when I woke up in the recovery room, the nurse – an ex-girlfriend of mine, Donna – looked at me very seriously and said: “We stopped halfway through the op. Just prepare yourself for a bit of news: we think it’s cancer.”

What was your first reaction?

Bizarrely enough – and this is genuine – at no point was I ever concerned about having cancer.

Really?

I know it sounds odd. But I entrusted myself to these people. They’re not allowed to say they can cure it, in case they can’t. But I could see in their faces that they could sort it out.

What did the doctors tell you when the diagnosis was confirmed?

They said: “The good news is it’s eminently treatable. You’ve got a ninety-six to ninety-eight per cent clear-up rate with this form of cancer.” I thought: “I’ll take those odds all day long.” Then they gave me the bad news: “It’s the worst of all the treatments.”

Why?

It’s classed as head and neck cancer. And the problem with treating the neck is that everything goes through it: food, blood, saliva, nerves. So when they zap it with radioactive waves, it fucks everything up.

How did you break the news to the band?

I just said it straight out: “Boys, I’ve got cancer.” Luke said: “None of us were looking your way.” I’m the youngest and supposedly the healthiest. As friends they were brilliant. But I told them to keep going with the album: “Work around me.”

When did your treatment begin?

That was March 2014. It was chemotherapy first.

What was that like?

The first one is a breeze. Second time, you start to feel sick. The third one, you’re puking up and feeling like shit. But the radiotherapy was the worst. They tattooed a little dot on my chest so they could pinpoint the radiation. That was my first tattoo. I’d always avoided them. It’s the permanency I wasn’t keen on – put a bird’s name on there and I might change girlfriend. But they bolted me to the table in a Frankenstein manner and fired a load of radioactive waves through my neck. And at that point I was on the fourth round of chemo, so you get the two combined, and that’s when you get knocked properly for six. You’re completely and utterly fucked. You’re conscious, but you’re really just concentrating on surviving. You don’t feel like you’re going to die, but you feel terrible.

Did you experience depression?

No. That’s something they keep their eye on. But what you have to remember is, I’m an immensely optimistic person. I was prepared for it. They kept asking me: “How are you feeling?” I said: “I feel like shit!” “But how are you mentally?” “Well, fine.”

Were you at home during the recovery period?

Yes. Donna, my ex, dropped everything to stay with me for as long as she could. And after she had to leave, my elder brother came to stay with me. I spent seven months of my life asleep, pretty much. You spend all day in bed. Your mouth turns into ulcers so you’re fed though a tube, a paste that gets pumped into your stomach. I didn’t eat proper food for four months.

Were there any complications?

The chemo knocks your immune system down to zero and I had to go back into hospital because I got a very mild infection. It could kill you. So they pumped me full of antibiotics. But the all-clear came around September.

And now you’ve got a tour coming up.

Yeah. The first show I’m doing is an arena. Nice one, boys. Work me in gently. Thanks! But there’s a little magic when we play together. Something happens that’s bigger than the sum of the parts. It gives you a massive amount of confidence.

Is there anything good that has come out of all that has happened?

Knowing how much people care. The ‘get well’ messages on our Facebook page, I read every single one. And by the end of it I was elated.

Do you cry easily?

Not really. But I did well up then. You know when people are being sincere, and I could feel it then. Like I said earlier, I feel very lucky.

Wonder Days is out now on earMUSIC.

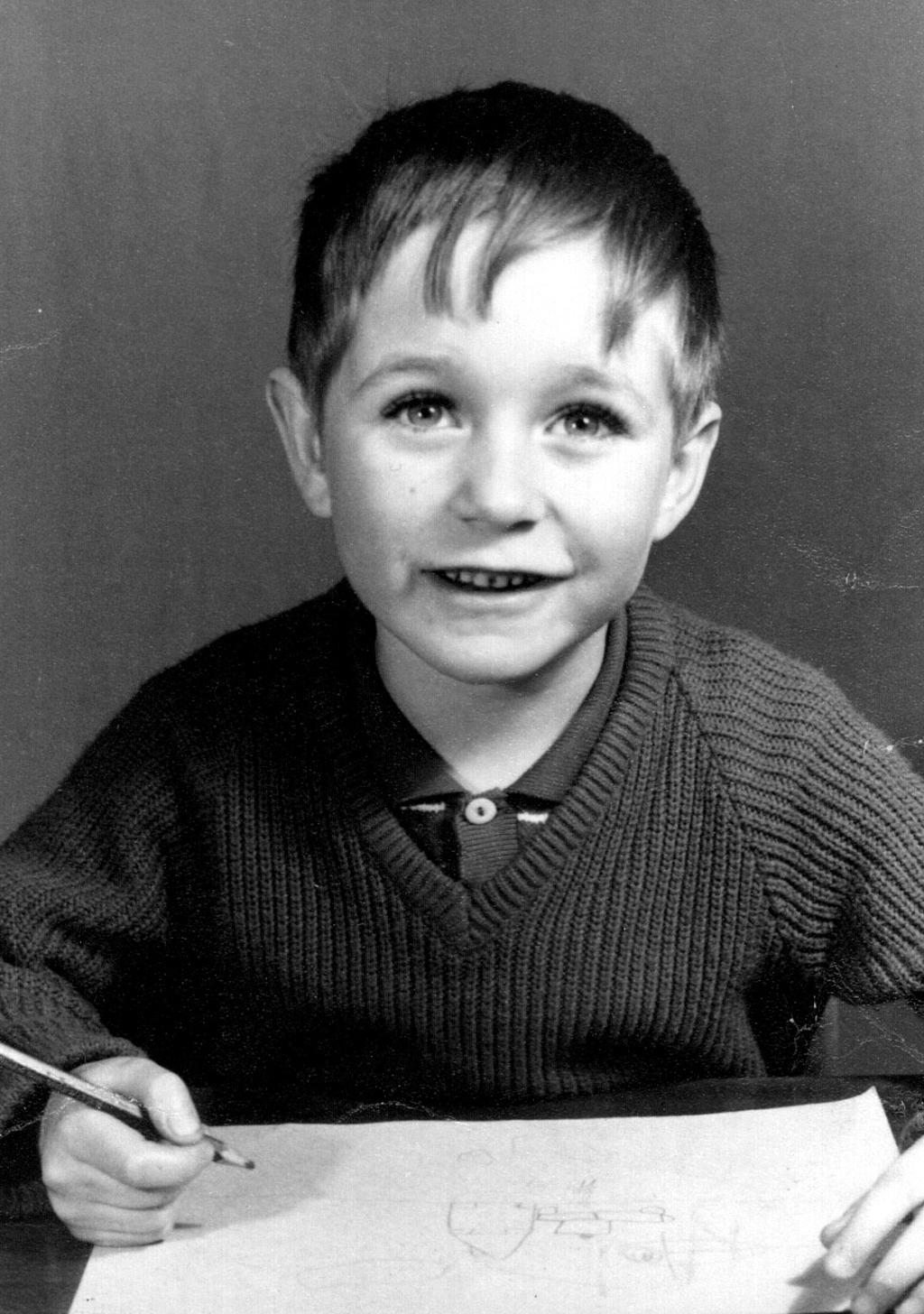

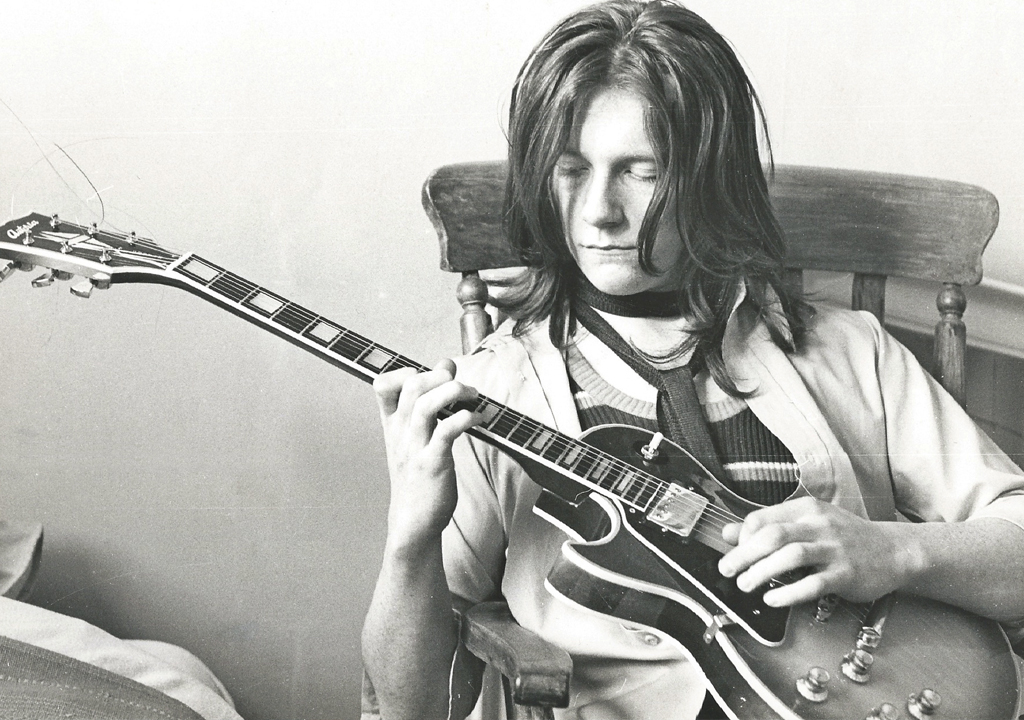

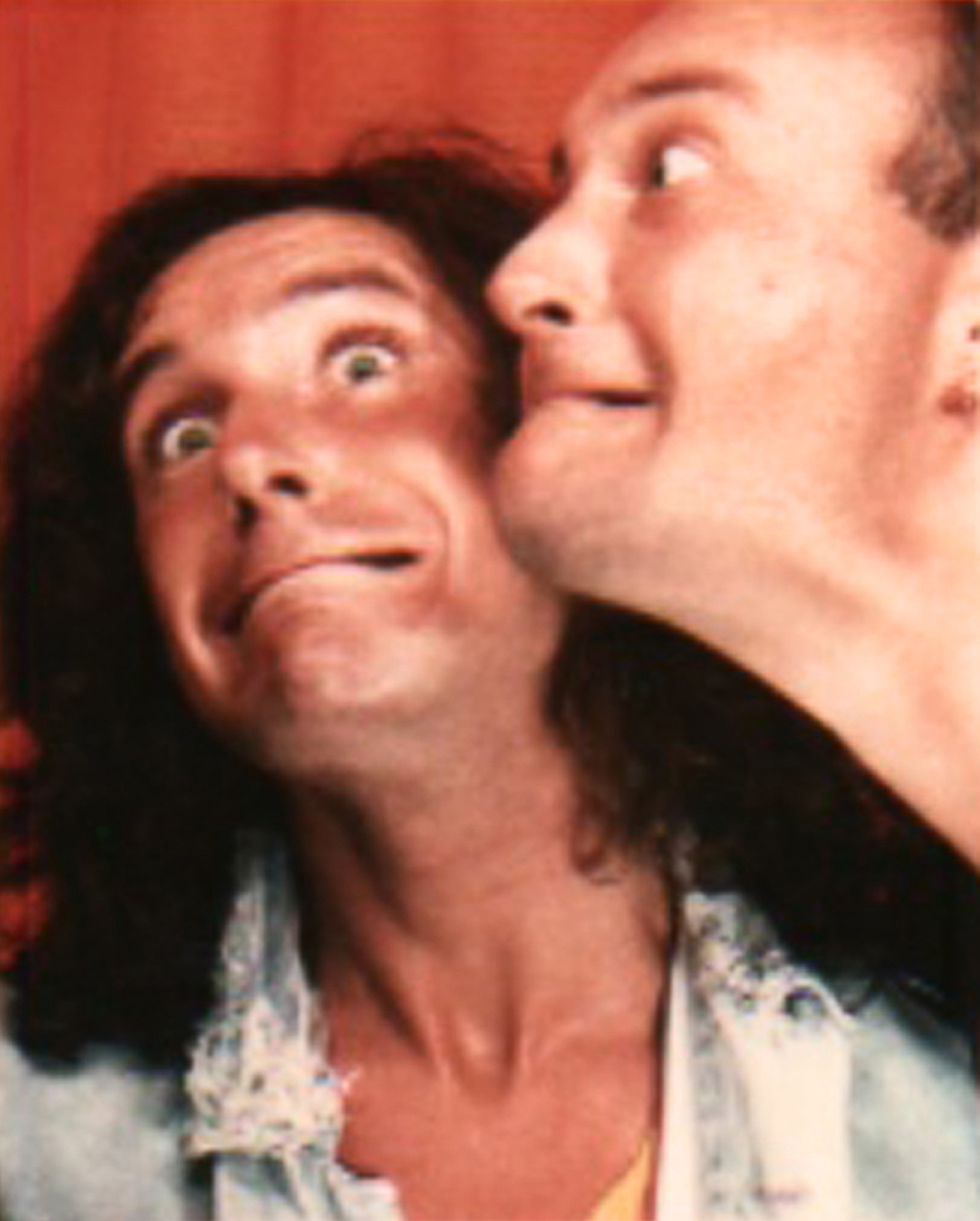

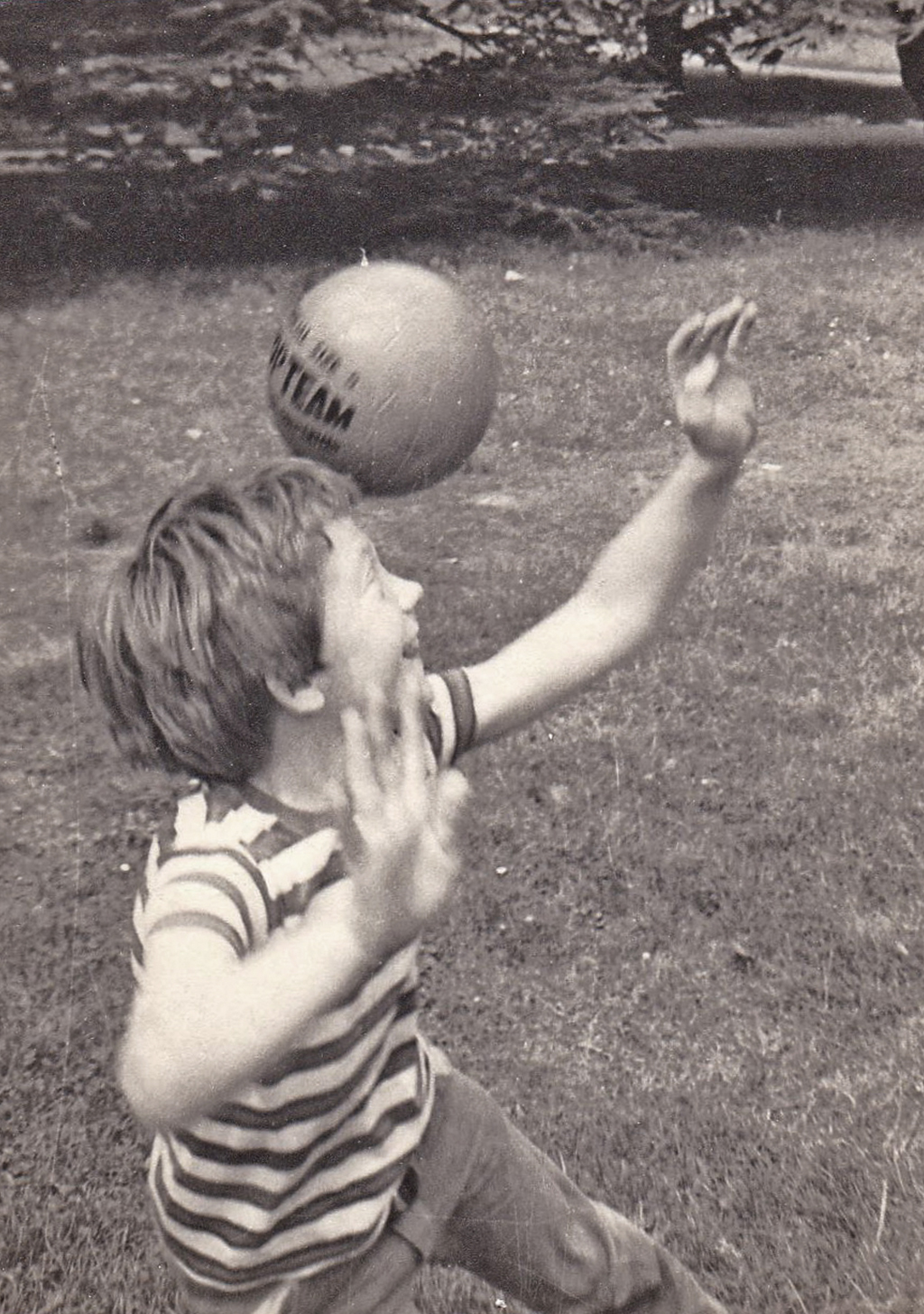

In the gallery: 1) A mop-top Ben Matthews 2) Danny Bowes in ‘68 3) Luke Morely in ‘77 4) Thunder convene at Haberdashers’ Aske’s in New Cross, January 8 2015 5) Ben as a teen rocker 6) Danny in ‘91 7) An early photo sesh for the band 8) Luke in Terraplane, 1982 9) Photobooth fun with Harry James 10) Luke in ‘69 11) Back to school 1: Danny 12) Back to school 2: Luke 13) Ben 14) Remember the days of the old school yard…