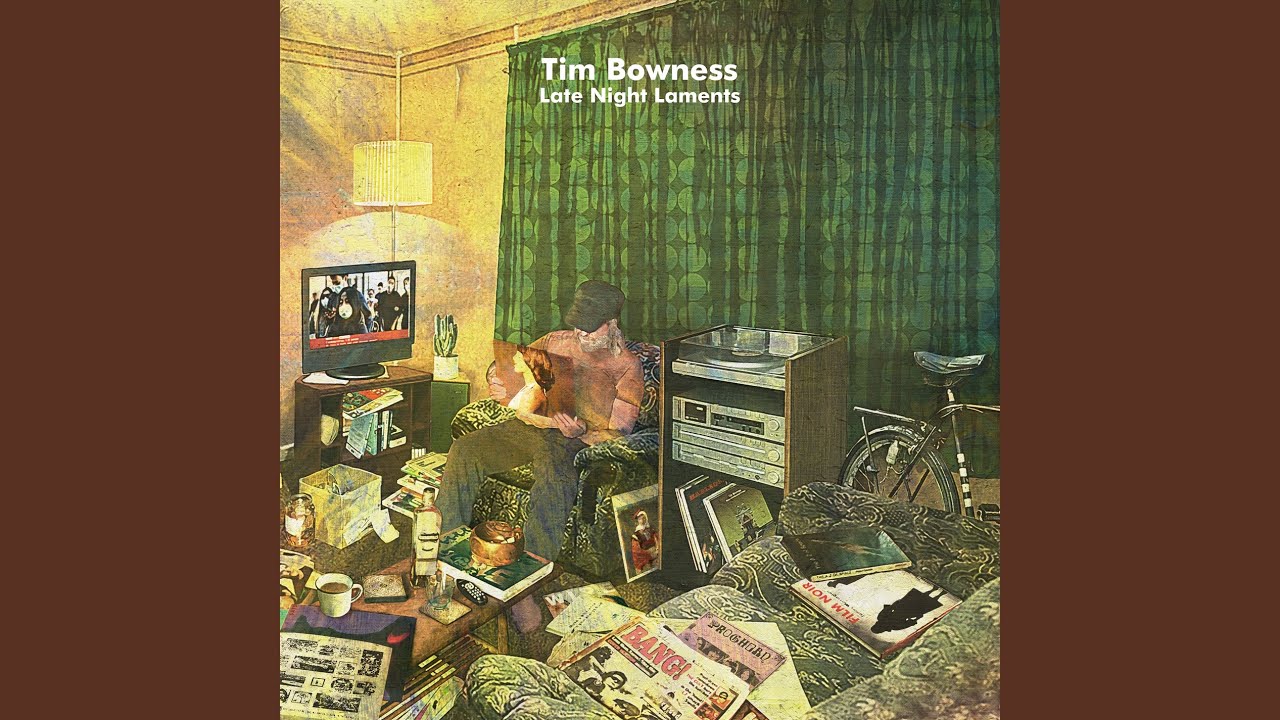

“Do I ever look at Steven Wilson and think, ‘Why is he having top-five albums and I’m not?’ No”: Tim Bowness found catharsis in exploring forced isolation on Late Night Laments

With songs for the lost and the lonely, detailing trauma and loss – but hardly ever his own – Bowness’ intensely personal sixth album is another fine addition to his impressive body of work

The coronavirus pandemic opened the floodgates of creativity for many prog musicians. As 2020 became a year to forget, No-Man’s Tim Bowness grabbed the opportunity to explore the idea of enforced isolation on his intimate sixth solo release, Late Night Laments.

Tim Bowness finished work on his new album Late Night Laments the day lockdown was announced. A self-professed news junkie, he’d seen the pandemic coming early. “I was aware of it from the very early reports in China,” he says. “I’d seen articles and said to my partner: ‘This could be the year unfolding.’”

The timing was purely coincidental. If there was any urgency, it came from the desire to complete a project he’d spent months obsessing over, rather than the prospect of massive societal upheaval. Because, as Bowness says himself, he’s nothing if not obsessive. “To the point where it would drive other people crazy!”

With Late Night Laments he’s made an album for the times. It never explicitly references lockdown or the pandemic – but its nine intimate, self-contained songs reflect the existential detachment of enforced isolation. Lyrically, it address the big, bleak topics in small, beautiful ways: death, loss, failure, rejection, missed opportunities and unfulfilled promise. It’s populated by the dead and the dying, the rejected and the lost. It’s too warm to be depressing, but there’s a rip tide of desolation just beneath the surface waiting to pull you under.

“I think in some ways it was an instinctive rejection of the more dynamic and upbeat Love You To Bits [No-Man’s last studio release] and Flowers At The Scene,” he says of the album’s two predecessors. “Clearly, I can’t allow too much light in for too long.”

He admits he isn’t one to hold back on things. More than once he apologies for “waffling” (he’s talkative but not a waffler). A day later, he sends an email expanding on some of the points he’d made and adding in others, not all of them strictly pertinent. (Who’d have thought he would be such a big fan of Motörhead’s 1979 album Overkill?)

But the Tim Bowness who made Late Night Laments is a solitary creature. The final track, One Last Call, was the first thing he wrote for the album. Inspired by the intricate yet stark spy novels of John le Carré, the song came to him late at night, when his partner and their nine-year-old son were asleep. Bowness played the music on his computer keyboard, singing it quietly to himself while the rest of the house was silent.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“By three or four in the morning, I had something that felt overwhelmingly emotional,” he says. “I played it to Brian Hulse [his chief collaborator on Late Night Laments and Flowers At The Scene], who liked it. And then the floodgates opened.”

One Last Call acted as a guiding light for the album. Many of the songs were written late at night or early in the morning; those that weren’t sound like they were. It’s as nocturnal as its title would suggest – a record that exists in a cocoon, sealed off from the world outside, its intimacy at odds with the blaring chaos of the world outside the window. “I saw it partly representing someone locked in a small world of favoured comfy chairs, records and books,” he says. “Locked in a beautiful sensation, while just about hearing the sound of the relentlessly bad news mumbling away in the background.”

the his sixth solo album, and his fifth since 2014. During that time, he also resurrected No-Man with Steven Wilson for 2019’s Love You To Bits, collaborated with Peter Chilvers on this year’s Modern Ruins and re-recorded the debut album by his 80s art-pop band Plenty. While he’s hardly been slack at any point during his 30-plus year career, this is a burst of productivity at a time when other artists of his age might be considering the long, gentle cruise towards retirement.

“There’s been more of an impetus to work,” he says. “Put it partly down to having a child nine years ago. In some ways it made me even more aware of my own mortality. And even more aware of how little time I had left to do things I considered to be important.”

He plays down the drama of his own early years, though it was traumatic by most other people’s standards. His parents had a volatile relationship: not so much a marriage as a constant battle marked by affairs, break-ups and reconciliations. “As I child I felt the brunt of it,” he says. “But although I saw arguments and devastation all around me, I wasn’t necessarily treated badly. And I think because I was in the middle of this chaos, I ended up getting more pocket money.”

I’ve always been optimistic. But when I find myself in spaces I was in when I was a kid, it can produce reflections that come through my music

His mother was killed in a car crash when he was 15. Shortly afterwards, one of his grandparents died and another ended up in a care home after suffering a series of devastating nervous breakdowns. “I became aware of how tragedy could just come into a life and tear it apart,” he says.

The Last Getaway centres around that notion of sudden, tragic upheaval. It was inspired by the cartoonist and author Harry Horse, who wrote a series of successful children’s books in the 80s and 90s. In 2007, Horse (real name Richard Horne) stabbed his terminally ill wife to death at their home, before killing their pets and finally taking his own life. “It was the emotional impact of such a devastating, bleak ending for this person who had written these incredibly sweet and sentimental books that my son really enjoyed,” says Bowness. “I felt profoundly sad that this was the end to the person that brought all this joy to people.”

The Last Getaway is a typical Tim Bowness song, in that it steers away from autobiography. He rarely writes about himself. “It’d have an audience of one,” he says. He isn’t being deliberately disingenuous here, although he is incorrect.

Still, there one track stems at least partly from events in his own life. The opening song, Northern Rain, is an elegiac, bittersweet portrait of an elderly couple in the grip of dementia, looking back at their lives and “happily coming to terms with their eventual deaths,” as Bowness puts it. The song was inspired (“in the abstract”) by his father’s own situation: Bowness Sr has severe Parkinson’s disease and his stepmother has dementia. “He hasn’t been out of the house since February and he’s left with my stepmum.” He laughs. “It’s a recipe for disaster!”

It’s a very Tim Bowness thing to say. The graceful bleakness of his music and lyrics seems to be at odds with the cheerful loquaciousness of the man who makes it. “It’s odd,” he says. “I’ve always been quite optimistic. Though there’s no doubt when I think back and find myself in those spaces I was in when I was a kid, it can still produce reflections that come through my music.”

Even before his mother died, Bowness found solace from the bickering in music, books and films. He would stay up late to watch the kind of fringe BBC Two movies other 12-year-olds weren’t allowed to, or journey into Manchester and come back with a bag of vinyl paid for by the inflated pocket money he received.

Steven is the only person more obsessive than I am

He graduated from The Beatles and John Barry to 10cc and Sparks and onto Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Roxy Music, Kate Bush and Talking Heads. Van der Graaf Generator and Peter Hammill were a key part of Bowness’ teenage years: the latter’s apocalyptic 1977 break-up album Over was a touchstone for him, its themes of trauma and loss dovetailing with his own. (He and Hammill live in neighbouring villages near Bath these days, and have become friends and occasional collaborators.)

Bowness knew early on that making music wasn’t just what he wanted to do – it was all he wanted to do. “I had no hopes for a conventional career,” he says, although that didn’t stop him trying. He briefly worked for the civil service and spent a couple of years working in NHS care homes, tending to elderly people who were considered too infirm for other homes.

He sat with them in their rooms, listening to them talking as well as they could about their lives, soaking up inspiration for songs he’d write years or decades later. “There’d be beautiful stories and strange stories and sad stories,” he says. Another wry laugh: “And then they’d inevitably die.”

His post-NHS musical career has been the ultimate slow-burner. He passed through a handful of 80s bands of varying artiness and sartorial extravagance before alighting in No-Man with kindred spirt and fellow musical traveller Wilson. The pair came into contact after exchanging letters in the late 80s. The first time they were in the same room together, they spent four hours talking about music and the next hour writing and recording two songs from scratch. “Steven is the only person more obsessive than I am,” says Bowness. The duo’s music podcast, The Album Years – essentially the sound of two men trying to out-nerd each other – bears this out.

No-Man’s brief tenure on hip indie label One Little Indian in the early 90s is the closest Bowness has ever come to mainstream recognition. Since then, he’s existed on the fringes, seemingly happy to be viewed as a cult artist, albeit one with a devoted fanbase and a very successful label-come-mail order website in Burning Shed.

At the moment, Late Night Laments seems like a conclusion to a way of writing and working

“Do I ever look at Steven and think, ‘Why is he having top-five albums and I’m not?’ Not particularly, no,” he says, adding that commercial success isn’t the imperative that drives him. “Music making has been emotional catharsis for me.”

Whether it’s down to a broad similarity in sound or simply regularity of release, the five solo albums Bowness has put out since 2014 all feel like part of a bigger piece. But he says the new record is an ending of sorts: not necessarily to the book, but at least to a chapter. “For whatever reason, at the moment, Late Night Laments seems like a conclusion to a way of writing and working. When I finished the album in March I felt as if I’d said what I wanted to say. As things stand, I genuinely don’t know what direction my future music will take, and that’s unusual for me.”

Tim Bowness being Tim Bowness, it’s unlikely he’ll be lost for words – literally or metaphorically – for long. Not while there’s any chance of the light creeping back in.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.