“Call me a punk and I’ll fucking cut you. I’m fucking serious. I don’t fuck around.”

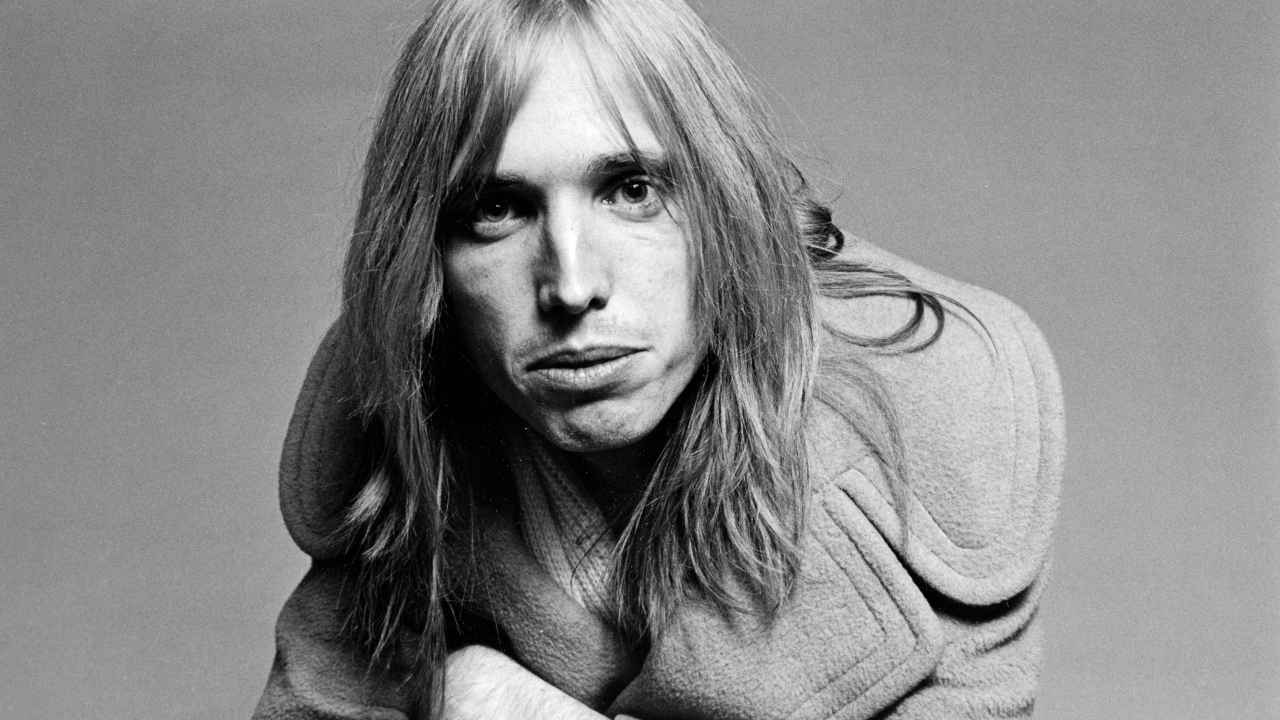

It didn’t take much to get Tom Petty’s blood up back in the old days. He was a natural-born malcontent with a black biker jacket and a smirking sneer plastered across his face. At least that was the impression the world got from the picture on the cover of the debut album from his band, Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers.

Turns out it wasn’t far from the truth. Petty had a high-sensitivity, low-tolerance bullshit meter, and continued attempts to hammer this square peg into the round hole of the punk rock movement was pushing the needle into the red. It was during an interview with Los Angeles magazine Back Door Man in November 1977 that he finally snapped.

“It’s a crock of shit,” Petty fumed. “From the beginning, I think because I have a leather jacket on they called me a punk. Don't fucking call me one. I don't like that. I ain't joining nobody's club, I've got my own club. I'm in a rock’n’roll band.”

Petty was right. He wasn’t a punk. But he was an eternal rebel. He conducted his entire career on his own terms, not least his battles with the music business and his refusal to be steered into doing something he didn’t want to do.

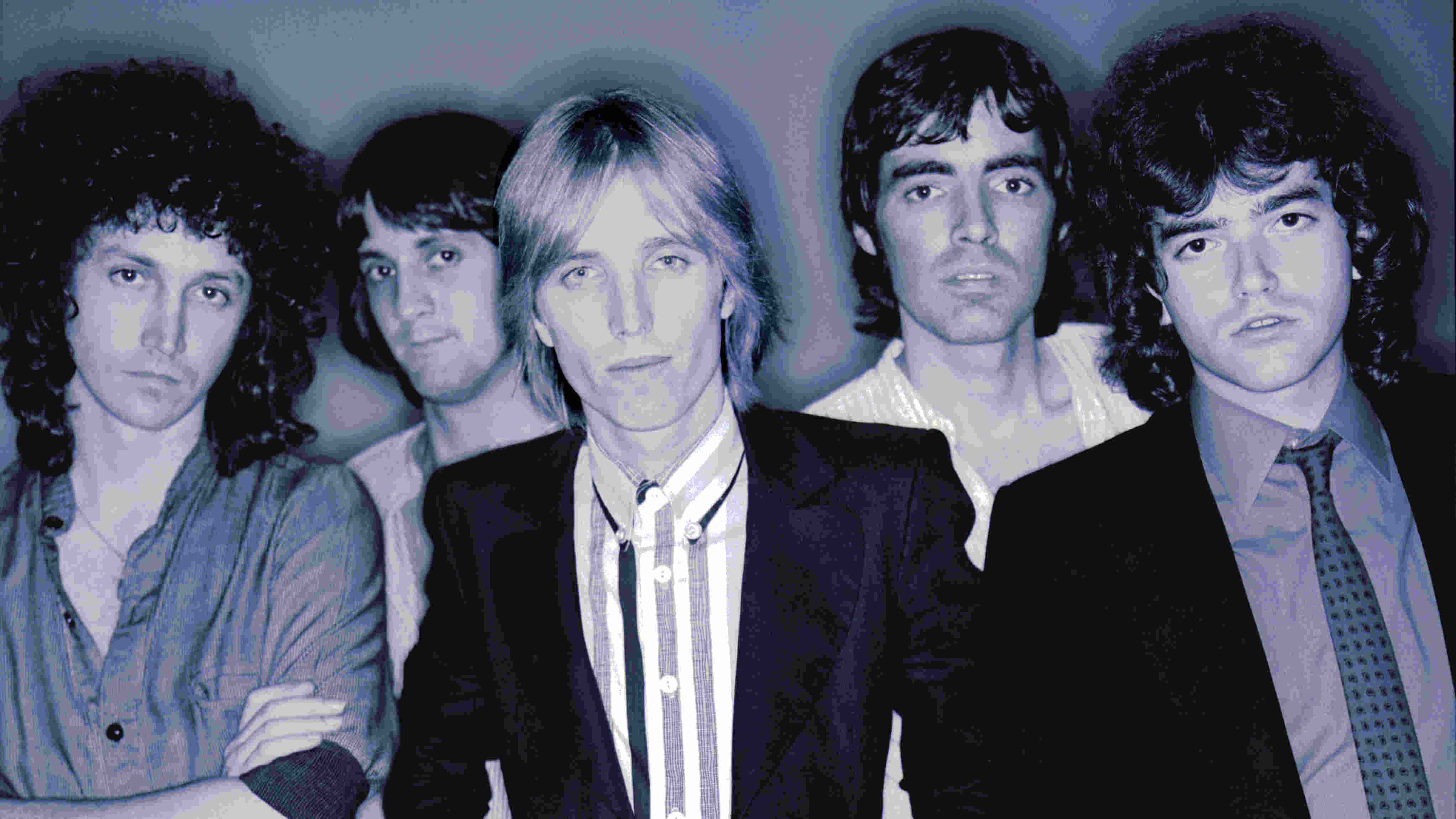

Petty was right about something else too. He was in a rock’n’roll band, possibly the greatest America has ever produced. The Heartbreakers weren’t epic myth-builders like Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band, or mystical poet-warriors like The Doors, or cocaine-dusted desperados like the Eagles. Petty himself was way more complex than his ornery hesher image suggested, but the way he saw it, he had one job to do. And he did it better than anybody.

“He could write the shit out of a song, he could sing the shit out of a song, and he kept that band together for over 40 years,” says Heartbreakers keyboard player Benmont Tench, a friend of Petty’s for more than 50 years.

Petty’s youngest daughter, Annakim Violette, puts it even more neatly: “He was an immortal badass.”

One of the main reasons Petty’s songs chimed with so many people down the years was because he connected effortlessly with the underdog. ‘Even the losers get lucky sometimes,’ he sang on Even The Losers, on his breakout 1979 album Damn The Torpedoes.

Petty wasn’t a loser, but he could have been. He grew up in Gainesville Florida, in a tough household. His father, Earl, was a part-Cherokee ex-US airman and a mean drunk. He would take his frustrations out verbally and physically on the young Tom, beating him black and blue more than once. “I got the fuck away when he was around,” Petty told Men’s Journal in 2013.

According to Annakim Violette, her father bore the scars of childhood throughout his life. “It was hard for him to carry that type of horrific pain, coming from a very impoverished, very ignorant family,” she says. “I think he overcame a lot of things from his childhood just by looking at himself through the characters in his songs. I think he saw them as a safe place.”

Petty would carry his own anger issues into adulthood. “I could really go ballistic,” he later admitted. “Any authority I didn’t agree with could make me go off.” Eventually he had therapy to work through his issues. “I thank everyone who put up with that for as long as they did,” he said.

Music was a safe haven for him as a kid. Like most baby boomers, his early years were soundtracked by rock’n’roll. In 1961, when Petty was 11, an uncle took him to see Elvis Presley, who was shooting the film Follow That Dream in Florida. “Elvis glowed,” he recalled, even though he never actually got to meet The King properly.

But it was the British Invasion that galvanised him. “The Rolling Stones were my punk music,” he later said, long after his aversion to the ‘p’ word had mellowed. He played in a few local bands – The Sundowners, The Epics – first on bass, then on guitar and vocals. Future Eagles guitarist Don Felder, another Gainesville native, worked at the store where Petty took guitar lessons.

“Tom had this amazing charisma on stage,” Felder says now. “He used to sing very much like Bob Dylan, this kind of nasally, almost whining type. But he came out with such conviction, and he sold you on his performance just by being so committed to it.”

Petty’s first proper shot at the big time was with the unpromisingly named Mudcrutch. Put together in 1970 with a couple of locals kids, among them future Heartbreakers guitarist Mike Campbell. Benmont Tench, three years younger than Petty, remembers being invited along to see them play at a dive bar in the summer of 1971.

“I went, ‘Holy shit, I love this band,’” he says. “I wanted to play with them from the moment I saw them play a bar. I followed them around from gig to gig. They would play obscure Dylan and Stones B-sides, early Gram Parsons songs, late Byrds songs, Rufus Thomas deep cuts. And now and then they’d do a song of theirs and it would be a knockout, and I’d find out it was something Tom had written.”

Tench was soon a member of the band. He watched Petty hone his songwriting. “His writing just kept getting better and better. That was always the thing – a good song, a good song, a good song.”

The singer was ambitious too. Mudcrutch had recorded a demo in Tench’s parents’ living room. Petty made the call that the band should move to LA and shop the tape around.

“I wanted us to be successful, but I had no idea how to do it,” says Tench. “Tom went: ‘Fuck it, I guess we go out to California to play them our tape.’ Him and Mike knocked on the doors of record companies, just walked into the lobbies and said: ‘Here’s us, we got a tape.’”

“It was a great, great time to be a young man in Los Angeles,” Petty told Men’s Journal in 2013. “It was the land of milk and honey; it was Shangri-la. And we had an adult portion of it – we took a big dose of LA. The audiences were just great, and we were free as birds. And there was an element that was fed up with what was going on, that was going to overthrow that, and this feeling that there was something in the air.”

Except things didn’t quite pan out. Mudcrutch made one single for LA indie label Shelter then just fizzled out, victims of a terminal lack of focus.

“My heart was broken when Mudcrutch broke up,” says Tench. “I always wanted to play with Tom and Mike.”

It turns out Petty felt much the same way. He stayed in LA to record a solo album, while the rest of Mudcrutch returned to Florida. But when Tench invited him to the studio to help out on a session by the keyboard player’s new band, Petty realised that surrounding himself with a bunch of studio musos wasn’t where he wanted to be.

“He went home and said to his producer: ‘I don’t want session players, I want a band,’” says Tench. ‘I want that band.’ And that’s the start of the Heartbreakers.”

Petty was 26 when he started working on the first Heartbreakers album. Not old by any stretch, but far enough down the line to know it could be his last shot.

“It was a business, not a party – we wanted to make a record,” Tench says of the sessions for the debut album. “Mudcrutch had fucked around in the studio for a couple of years and never come up with enough tracks to release. His solo thing hadn’t worked out. This time it was, like: ‘Okay, let’s make this happen.’”

But the man whose name was up front wasn’t going to kiss the ass of anybody to make it. Case in point: on the back of a growing buzz in Britain, the band were bundled on to former Neil Young guitarist Nils Lofgren’s 1976 UK tour as support. When Lofgren and his roadies wouldn’t allow drummer Stan Lynch to set up his riser at one show, Petty refused to play. “We were arrogant, asshole bastards,” he later said.

He wasn’t above going to war with his own record label, either. In 1979, when his original label Shelter was sold to MCA, he filed for bankruptcy in an attempt to extricate himself from an unfavourable contract – a moment of righteous brinksmanship that worked when MCA caved in, and rewarded him with a much improved deal.

He dug in again when the label wanted to release 1982’s Hard Promises at the ‘superstar pricing’ of £9.98 rather than £8.98. Petty figured it was a rip-off. He considered refusing to release it, or releasing it under the fuck-you title Eight Ninety Nine. Once again, the label backed down.

“Tom had a sharp eye for everything,” says Tench. “He wasn’t suspicious, but he was smart. He wanted to keep an eye on the business. The idea that we should do something we thought wasn’t right just because the record company thought it would sell, well we weren’t going to do that.”

MCA got a revenge of sorts at the end of the 80s, when Petty presented them with his debut solo album Full Moon Fever, and they rejected it.

“I was hurt so bad,” Petty told Esquire in 2006. “I’d never had anything rejected. I’d never really even had a comment, so when that happened it was really just a board to the forehead.”

Rather than scrap the record, he decided to bide his time. “I waited a while until the top regime at the record company changed. And then I came back and played them the same record, and they were overjoyed.”

Full Moon Fever would become his most successful album. The title of the first single from it was apt: I Won’t Back Down.

Petty could be intractable, but he picked his battles carefully. He was an unlikely pioneer in the MTV era; the promo for 1982’s You Got Lucky is a contender for the first narrative video. “Some of my peers were very intimidated by it,” he later said. “I thought: ‘Let’s just dive in.’” His reasons weren’t purely artistic, though: “We were just tired of doing those damn lip-syncs.”

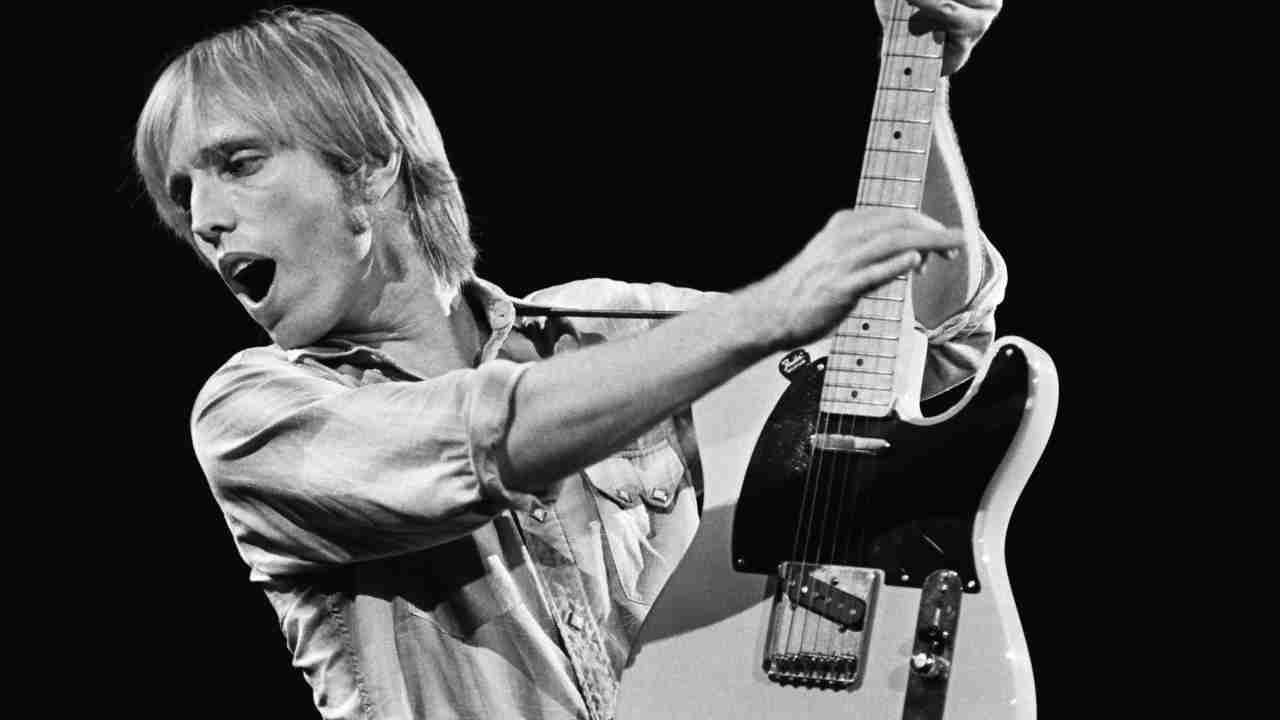

As a songwriter, Petty nailed his colours to the mast early on: he was a rock’n’roller through and through. The run of early albums, from Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers through to 1982’s Hard Promises, were brilliant in their economy – of songwriting, of length and of intent – as much a reaction to the glossy ‘corporate rock’ of bands like Foreigner and Boston as punk had been. Even when the production got lusher and the track-listings got longer, he never lost sight of his own personal north star.

“We’re a real rock’n’roll band, always have been,” he told the LA Times just a week before he died. “And to us, in the era we came up in, it was a religion in a way. It was more than commerce, it wasn’t about that. It was about something much greater. It was about moving people, and changing the world, and I really believed in rock’n’roll – I still do.”

He made it look effortless, but it wasn’t. “He worked hard to make it look easy,” says Tench. “I’ve never known anyone so focused as Tom.”

Even in middle age, the Heartbreakers came across as a gang. Petty may have stepped away from the band occasionally to make his solo albums, as well as joining the late-80s supergroup the Traveling Wilburys alongside Bob Dylan, Roy Orbison and his good friends George Harrison and Jeff Lynne, but he always returned to the mothership. And like all gangs of boys, they had a mantra: “There’s no girls in the Heartbreakers.”

Fleetwood Mac singer Stevie Nicks found this out in the early 80s. Nicks became close to Petty via her then boyfriend Jimmy Iovine, who had produced Damn The Torpedoes. She made it clear that she wanted to join the Heartbreakers.

“Oh, she wouldn’t quit,” Petty later recalled. “Stevie showed up at my house every night for a year. We gave her a hard fucking time: ‘No way you’re coming to a session. Look at the fucking clothes you’ve got on.’ The fact that she stuck around was amazing.”

The pair eventually teamed up on Nicks’s 1981 solo single Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around, co-written with Mike Campbell. She returned the favour by singing on Insider, on the Heartbreakers’ Hard Promises album, the same year.

“He could absolutely be friendly and welcoming, and he was very, very fucking funny,” Tench says of Petty’s approach to outsiders. “I don’t know anybody who met him and didn’t like him. But he could be intense.”

One of the most notorious instances of that intensity came during the making of 1985’s Southern Accents, a semi-concept album about the South produced by Dave Stewart of the Eurythmics. Petty got so frustrated trying to record the song Rebel that he punched a wall in sheer anger, breaking his hand. It was the culmination of bigger issues in his life.

“At that time in my life, my marriage, and just about everything else, was on the rocks,” he later recalled. “I was just overindulging more than I should – the brandy was coming around more often. I was hitting all sorts of walls.”

Gang or not, the Heartbreakers weren’t free from their own tensions, not least between Petty and drummer Stan Lynch. The extroverted Lynch was a different personality type to his more introverted bandmates, and he and Petty butted heads more than once. “The cat’s just pissed,” the Lynch once said of Petty. He would eventually be fired in the early 90s, after one bust-up too many with Petty.

Long before that, no one was under any illusion who was boss. “Every band needs a leader,” says Tench. “We’d kind of tried it in Mudcrutch, but it didn’t work. That’s why Tom’s name was upfront.”

Towards the end of his life, Petty had a more benign view of his leadership role. “They don’t view me as the boss,” he said of his bandmates. “They view me as the petulant brother that you sometimes have to listen to.”

Petty had long left his troubled childhood in Florida behind him, but the echoes of it carried down the years. “He had no guide book for a normal, healthy family environment, or how his role as a father should be defined,” says Adria Petty, his eldest daughter. “That confused him and troubled him towards the end of his life. He felt like he hadn’t delivered for us as much as he could have done. The flip-side is that music is where he found his purpose and where he was happy. You don’t really want to begrudge someone that either, if that’s the reason they’re on the planet.”

Adria and her sister Annakim had a unique view of their father. To them he was Tommy, the guy who loved to watch Stanley Kubrick movies, or horror or comedy films. He had a wild sense of humour, something born out when Petty appeared as a recurring guest on the animated TV show King Of The Hill, playing Lucky, a character pitched by the show’s creators as “looking like Tom Petty without the success”.

“He was really into surrealism, and dad raised me from an early age to be very arty,” says Annakim. “But there was something very grounding about how connected he was to his craft.”

Petty’s home life wasn’t always easy. His relationship with his wife, Jane, who he married in 1974, was sometimes fractious. The pair went through turbulent times in the 80s and 90s. Then, after 22 years of marriage, they got divorced.

“It was a really hard thing,” he said of the split, in an interview to promote 1999’s uncharacteristically dark Echo album, an album that was informed by his martital problems. “I had to put my life back together.” In the same interview, he addressed the album’s mix of defiance and desperation. “The defiance is the part of me that’s trying to keep from sinking into oblivion,” he said ominously.

There was something he wasn’t letting on. In the wake of his divorce from Jane, Petty had to fallen into depression and had turned to heroin to numb the pain. He had long between an ardent spliff smoker. “I’ve had a pipeline of marijuana since 1967,” he said in 2013. He’d done his share of cocaine too. “I mean, I went through the 80s like everybody, but cocaine was never a good look.”

The Heartbreakers weren’t strangers to the hardest of hard drugs. Longtime bassist Howie Epstein had been using the drug since the mid-80s, and his behaviour was becoming more erratic. But no one expected Tom Petty to become a junkie in his late 40s.

“When I realised that he was taking heroin, I was really frightened and I was really sad,” says Benmont Tench, who had overcome a serious cocaine addiction in the late 80s. “I was a little mad at him, which is irrational, because as a recovering drug addict I know that that shit gets you. You’re basically fucked once it gets you. You don’t have any control any more. But I was frightened for him and there was nothing I could do.”

“I wasn’t a guy that grooved on being a junkie,” Petty told Warren Zanes, author of the excellent 2014 book Petty: The Biography. “I was more of a clandestine drug addict.”

Still, he was in deep trouble and getting deeper. “You realise one day: ‘Shit, I’ve lost myself. I’m hanging out with people I wouldn’t be seen with in a million years and I have to get out of this. Using heroin went against my grain. I didn’t want to be enslaved to anything.”

After failed attempts to kick the drug cold turkey, Petty finally enlisted the help of a doctor who prescribed him medication to help wean him off the opiate. “They made me eat [pills] every day for months and months and months,” he recalled. “And I started to feel alive again.”

Petty had gotten himself clean. Howie Epstein wasn’t so lucky. Petty reluctantly fired the bassist from the Heartbreakers in 2002 due to the latter’s ongoing drug addiction. A year later Epstein was dead.

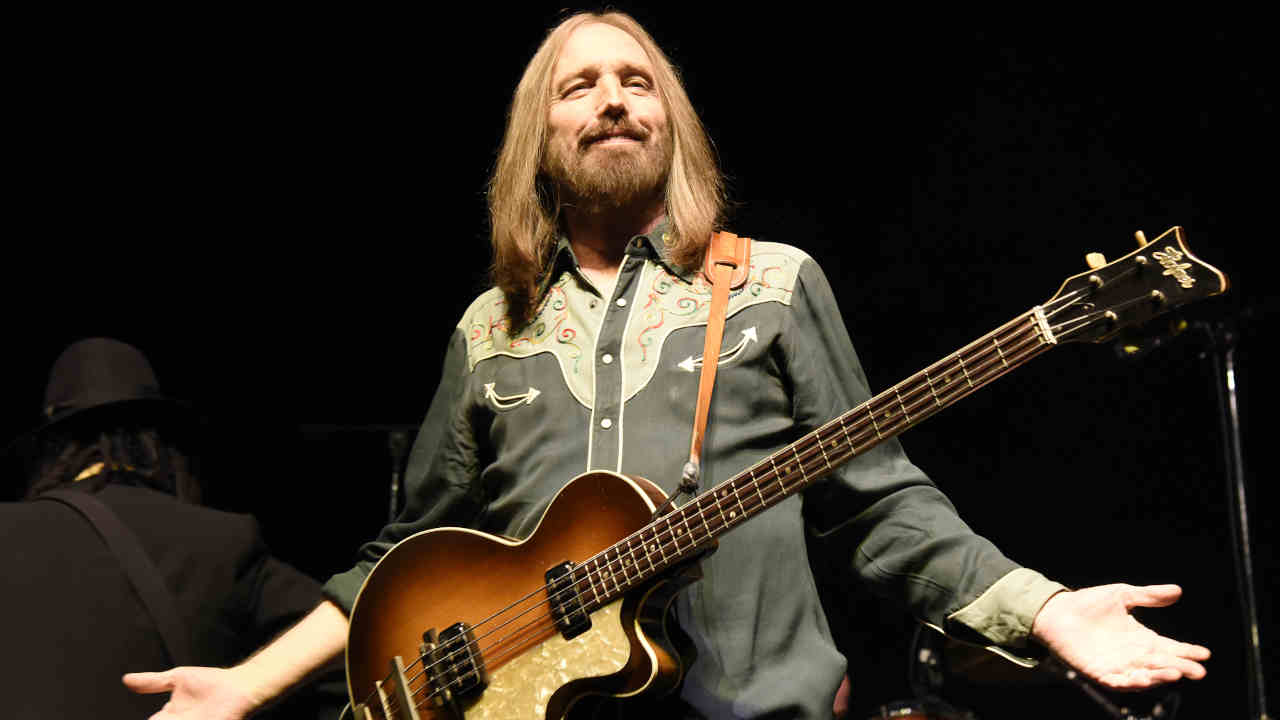

Tom Petty might have been an immortal badass, but even he admitted that he couldn’t do this forever. “I don’t know how much more of this we’re gonna do,” he told Rolling Stone in 2017. “Every show is precious, and I’m just really having fun.”

He was talking in the middle of the Heartbreakers’ 40th-anniversary tour. Petty had pitched at the band’s last big hurrah, which observers took to mean he and the band would be stepping back from the stage.

“He never said it was the last tour, he said it was the last big, long tour, playing big places,” Benmont Tench says today. “By the end of it he was like: ‘Damn, we can just take a couple of years and come back and play stadiums. I’m never breaking this band up!’ He was charged. And that’s how he was before those last gigs.”

On September 21, 2017, the Heartbreakers played the first of three 40th-anniversary shows at the Hollywood Bowl. Before they went on stage at the last show, Petty asked Tench what he was doing afterwards. “He said: ‘I’m going to get everybody together in this hotel room.” Tench had made plans to meet friends elsewhere and couldn’t make it. He told Petty he’d call him in a couple of weeks. “I figured we’d check in, and within a month or six weeks we’d get together and just jam.”

After the final show, the band posed for a group photo and gave each other a hug and said they’d see each other soon. Then they all took off. It was the last time Benmont Tench saw the man he’d known for more than 50 years.

“A week later to the day, I get a phone call in the middle of the night,” he says. “He’d been rushed to hospital.”

Petty had been found on the floor of his house, unconscious and not breathing. He had accidentally overdosed on a mix of prescription drugs, including Fentanyl, the same opioid that had a part in the death of Prince 18 months earlier. Petty had been taking the drugs to alleviate the pain from a fractured hip, among other things. He was rushed to hospital but he never recovered. On the evening of October 2, 2017, it was announced officially that he had passed away.

Today, Benmont Tench still can’t quite believe the man he had known since his early teens is gone. “I knew he was in pain from his hip,” he says. “Other than that he seemed pretty strong. I figured he’d go get his hip replaced and we’d carry on. But that never happened.”

In the past 12 months, Tom Petty has been memorialised the best way possible: via a pair of compilation albums. One is An American Treasure, a four-disc box set which delves deep into the Petty archives, pulling out lost gems and out-takes among deeper cuts. The other is The Best Of Everything, a glorious 38-track collection which spans the 40 years between his debut album and 2014’s Hypnotic Eye, the final Heartbreakers album.

There’s still unheard material in the archives, according to Tench, although a lawsuit between Petty’s daughters and second wife Dana York over alleged misappropriation of his estate might mean it won’t see the light of day. “I don’t know what’s gonna come of it,” he says.

He knocks back the idea that the Heartbreakers could follow the likes of Queen and carry on without their former leader. “I don’t see how. You can never say never, but he was the centre of the whole thing. His writing, his singing. His guitar was the foundation of the rhythm. It was all centred around that guy singing, playing his songs.”

And Petty himself? What would the kid in the black leather jacket threatening to cut anybody who called him a punk make of his status as a great American icon. Both of his daughters have an answer.

“He would have loved it,” says his daughter Adria. “He was always: ‘Look at me, I’m a living legend.”

“He loved Elvis, he loved iconic shit,” adds her sister, Annakim. “He had enough miles on him to be called an icon.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 266