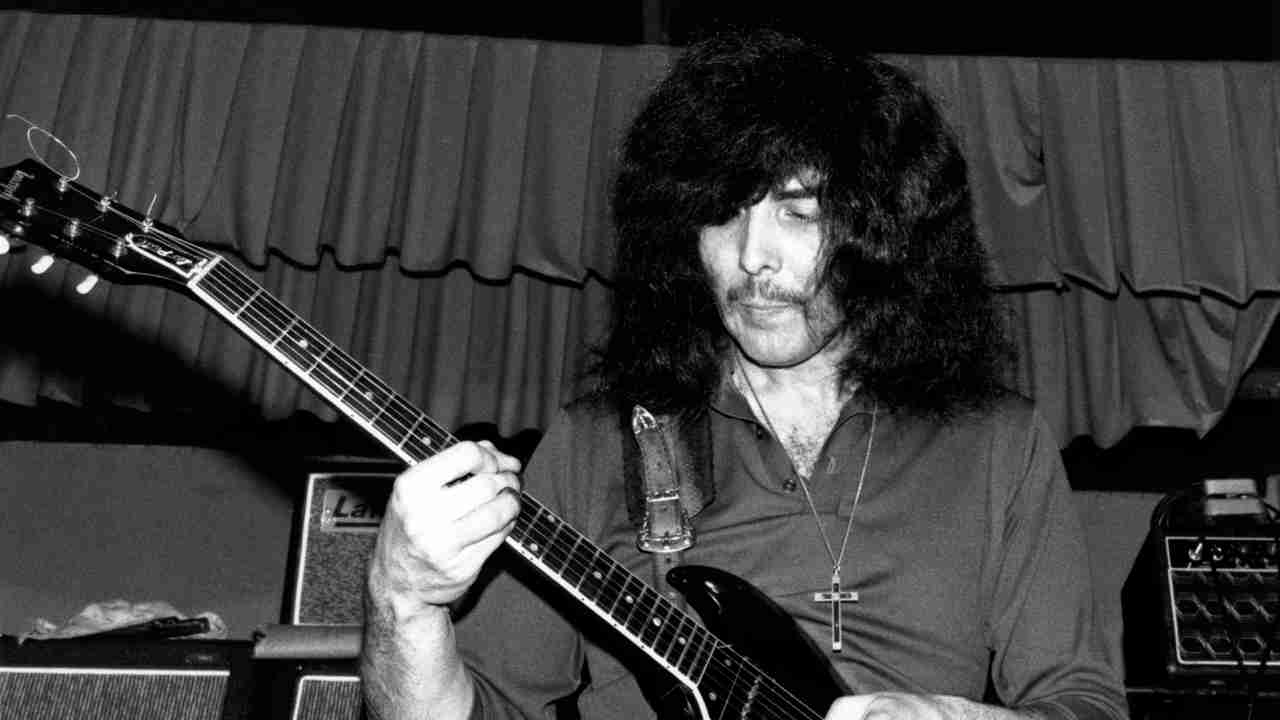

Black Sabbath guitarist Tony Iommi may have been the king of metal riffs onstage, but offstage he was a fiercely private – at least until he published his autobiography, Iron Man: My Journey Through Heaven And Hell With Black Sabbath, in 2011. Metal Hammer caught up with Iommi when the book was published to look at the events that made him the man he was.

Tony Iommi has never been a man to use his private life to foster celebrity status. While others have invited the world to invade their privacy in search of ephemeral fame, the Black Sabbath guitarist has always refused to talk about such matters. All that has changed with his autobiography, Iron Man: My Journey Through Heaven And Hell With Black Sabbath, in which he has revealed a lot more about himself than ever before.

“I can’t say I am very comfortable with telling everyone what’s gone on in my life outside of music,” he says. “But I knew that if I was to do this book, that side of things had to be faced.”

Many who know him will be surprised that Iommi has chosen to do the book at all. Often reticent when faced with being in the spotlight offstage, the quietly spoken metal hero has never given the impression he’s keen to write his memoirs. But, having made the choice, the result is very much a reflection of the man: frank, honest, funny, entertaining, upbeat.

For Iommi, one of the biggest problems was that much of his life with Sabbath was so well documented there was hardly anything more to say. Which makes the other side of his story – the hitherto unrevealed private section – even more fascinating. For instance, the fact that he is an only child.

“I can’t say how that affected me compared to those who had brothers or sisters. Well, there was a time when my parents took in this guy. He was our lodger, but slept in the same room as me. I hated the situation. Suddenly, I wasn’t the centre of attention. It seemed to me I was being sidelined for someone who wasn’t even family.”

He looks a little tense as he talks about his upbringing and the way it affected him. But that’s part of the learning curve. Once you’ve gone public with this information, you have to expect to be probed about it.

“My paternal grandfather had money, although that didn’t mean my father did. In fact, we really didn’t have much. The first house we lived was OK, but when we moved to a shop in Aston, I hated it. The carpet and lino were wearing badly, and my room was just so small. There were boxes all over it, which cut the size down even further. It was a horrible time. And the area was also bad. Lots of gang problems.”

Yet it’s this very grimness that many believe helped to turn Birmingham into the home of metal. It’s something of which Iommi is fully aware. In fact, he recalls vividly what it was like to be a young, aspiring musician in the city.

“It was very different type of community to, say, London. But we didn’t all know each other, despite playing in the same venues all the time. Sabbath knew Robert Plant and John Bonham from Led Zeppelin. They were local lads and John was in a different band every week, or so it seemed. He ended up being the best man at my first wedding. But the attitude in Birmingham at the time was that if you were in a band, then you stuck with them. You didn’t go off and play with others – that was seen as being disloyal. Today, everybody seems to have side-projects and plays with anyone. But in the late 1960s, if you were in a band, then that’s where you belonged. It was like a gang mentality, and you never changed gang membership!”

This sense of belonging together gave a lot of the local acts a feeling of camaraderie, something that perhaps helped to keep the city apart from other areas of the country where the loyalty factor was overridden by the demand for success. And Iommi still remembers Sabbath’s first ever London gig with a shudder.

“We played the Speakeasy, and we just felt out of place. Everyone looked so posh compared to us, and we really didn’t belong there at all. It took us ages to come to terms with London.”

It wasn’t only in the capital where Iommi had a sense of unease. If he turned to his family, he’d have his musical aspirations derided.

“Everyone – my parents, cousins, the whole family – kept telling me I needed to get a proper job and stop wasting my time. Well, I did have a job in a factory, but I was committed to being a professional musician.”

However, attitudes weren’t totally cut and dried. Iommi’s mother, in particular, actually played a role in helping the band.

“My dad liked Ozzy a lot, and thought he was really funny – which he was. But it was my mum who helped us out. She’d put up the money for us to hire a van for a gig. But then an hour later, she’d be going on at me. ‘When are you getting a proper job?’ she’d say like everyone else. It confused me, so much, the switch from being supportive to suddenly being the opposite.

“My mum came to a few gigs in the early days. But she thought we were too loud!”

Attitudes changed in the Iommi family when the first Black Sabbath album came out.

“Oh, that’s when everyone was suddenly proud of me and what I’d done,” smirks the guitarist. “Members of the family would go round telling everyone that they were my cousin, uncle or whatever.”

It wasn’t just his family who failed to take Black Sabbath seriously. The band were shunned by the city of Birmingham for years.

“We were ignored for so long. That’s why it means so much that the city council gave their approval recently for the Home Of Metal exhibition, which celebrates what Birmingham has done for metal. Recognition at last.

“Up until this happened, we were ignored, and we’ve always not only been proud to be from here, we’ve also actively supported what’s going on. We’ve never made any big fuss about it, but Sabbath have donated money to hospitals for beds and much-needed machines, and to other local charities. The thing is, we did it without looking for publicity.

“I do remember a while ago when someone suggested the council erect a statue of us. It was covered on the local TV news, and afterwards two women said on air (adopts a sneering voice), ‘They want to put up a statue to them?’ So, I’m glad for the acceptance now.”

No rock autobiography would be complete without drug stories. And Iommi doesn’t hold back about the excesses he and the rest of Sabbath enjoyed during the hedonistic 1970s. But he’s also prepared now to talk about how hypocritical he was in the mid-1980s.

“When Glenn Hughes was in Sabbath (for the 1986 album Seventh Star), he was having major drug problems. In the end we had to get rid of him because of it. He was doing so much coke. By then I was off the stuff, although I’ll admit I did have the occasional line. So I was guilty of having a go at Glenn about his problems, while sneaking off to have a little myself!”

Iommi reveals that, for him, breaking the drug habit wasn’t as tough as it was for others.

“I’ve always been lucky in that I can stop doing something when I want. I did it with coke, also drinking and smoking, I just quit them. Sure, I did have the very occasional lapse, but I’ve not done even that for years. What happened was that when I lived in LA, coke was so easily available that it became very natural. You didn’t have to go too far to get any. But when I moved back to England, it was so much harder to find. And that encouraged me to quit.

“My second wife, Melinda, was always good at spotting when I’d been doing drugs. It didn’t matter how much I’d lie and deny it, all she’d say is, ‘I can tell when you’ve been doing it!’”

Iommi has three ex-wives (he’s now married to Maria Sjöholm, who is described in the book as the love of his life), and the guitarist admits writing about those relationships meant he had to re-examine what went wrong with them.

“It would have been so easy just to have laid the blame on the ex-wives – and so wrong. I was at fault in my own way each time. So I had to be totally honest and tell it like it was, not like I wished it had been. I did cheat with other women, and there were other things that led to the break-up of each marriage. But that was one of the hard things with this book – opening up my private life the way it had to be done.”

Iommi also had to expose his innermost emotions over the death last year of Ronnie James Dio. And, sitting here even now talking about that painful moment clearly upsets him.

“It was the first time I’d seen a current bandmate die. We lost Ray Gillen [Sabbath singer in the mid-80s], but that was several years after he left the band. It was such a shock. Geezer was in LA with him all the time, but I was over here. One day, Geezer called and said that Ronnie’d taken a turn for the worst. I said I’d fly straight out, but he said, ‘You might not want to see the way he looks now.’ But before I could arrange to go out, he died.

“The thing is we were all getting on so well in Heaven & Hell. The problems we had in Sabbath when Ronnie was in the band were down to egos clashing, and we’d grown out of that. I’d learnt not to react when Ronnie blew up. You let it go and it passed. Before, I’d have a go back at him when he was in a mood, so things got worse.

“One of things about the funeral that sticks in my mind was seeing Ronnie’s body in the coffin. They’d done a very good job in hiding what the illness had done to him physically.”

As with anyone writing their life story, Iommi faced the publishers’ axe when it came to content. He had to cut out a lot of material, but he doesn’t feel that the book’s been compromised.

“I’d written a lot about my friends, but it was all very boring. Who wants to read about how I go out for dinner with them? It isn’t the sort of riveting stuff you expect from a book like this!

“I’ve had a lot of people ask me if I’ve written about them. I had Bev Bevan [an old friend of Iommi, who was briefly in Sabbath during the early 80s and appears on The Eternal Idol album as a guest] asking me the other day. I told him what I tell everyone: buy a copy and find out!”

Now it’s written, he certainly won’t be at a loose end, with plenty planned and rumoured. There are persistent reports of an original Black Sabbath reunion for a tour and possibly a new studio album. But the guitarist is far too wily to give anything away on this front.

“There are always stories. The Birmingham Mail took comments I’d made off the record and printed them as if it confirmed we were back together. I was indulging in speculation with a journalist I thought I could trust. Right now there’s nothing to say on the subject.”

But on stronger ground, Iommi is getting involved with the movie world. He’s signed up to compose the music for three films.

“It’s a deal with Mike Fleiss. He produced The Texas Chainsaw Massacre remake and Hostel. The first film will be a horror movie. Will I have a part in it? Absolutely not!”

For Tony Iommi the future stretches out as an exciting challenge.

“I’ve always had a positive attitude to life. Whenever I’ve been knocked back, I get up and start again. I did it when I lost the tips of two fingers in an industrial accident when I was 17. Doctors told me that I had no hope of playing guitar again. I refused to accept that. When I heard what Django Reinhardt, the jazz guitarist did with just two fingers it inspired me to find a way to carry on and become a musician. After that anything was – and is – possible!”

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue 224, September 2011