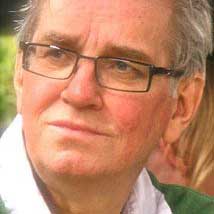

Brooklyn-born Tony Visconti has played a key role in the development of rock music since the early 70s, producing – and sometimes playing on – classic albums by David Bowie, Marc Bolan, Thin Lizzy and others. In this archive interview from 2007, he looked back of his career as a collaborator with some of rock’s greatest artist.

The Move

Flowers In The Rain was my ticket to ride. Denny [Cordell, producer] wanted to throw it away as he thought it was flawed – the middle section not rocking enough. So I said I could rework the middle section. He asked how much it would cost, and I said: “It’s something like nine quid a man times four. I’ll write the part for free, but what the hell, I really rate this song. You shouldn’t throw it away.”

And it turned out so good that its highest chart position was No.2 [September 1967]. And it was the first song that was ever played on Radio 1. Tony Blackburn comes on and says “Welcome to Radio 1. And here’s Flowers In The Rain by The Move.” I couldn’t believe it. A great feeling.

Marc Bolan

As a producer, I needed to find someone to grow with. My assignment from Denny was to get a band of my own. It was so easy. The first night I went out I found a band called Tyrannosaurus Rex. I knew that whoever the next Beatles were going to be, they would be very weird. And I got that feeling when I saw Tyrannosaurus Rex.

Marc and I had the same level of experience, which was virtually nil. We were a perfect foil for each other. I reckoned with my producer chops being so limited I could produce two people, and proposed that to Marc. I was in the studio with them a month later.

I didn’t do a great job on that album at all. It was my first album and was called My People Were Fair And Had Sky In Their Hair… [1968]. I can’t even listen to it.

The one thing that turned out great from those sessions was Debora. We only had four days’ studio time. Denny said: “Here’s 400 quid. Go and do an album. We spent most of those four days making sure Debora was perfect. I’m proud of that. That came out just the way we wanted it. Looking back, to have such a strong sound with just an acoustic guitar and a bongo drum is just amazing.

When he wrote Ride A White Swan, it was so simple and basic that he said maybe we should put strings on it. So I begged my boss to let me go back in the studio, and we got four violinists to play that sublime arrangement.

It was a peak moment in my life when I was told it was No.2. Marc and I turned white. We thought we should celebrate. We went out to Cranks vegetarian restaurant in Soho and got all the change out of our pockets and bought a nut rissole and a carrot juice. We had a No.2 record and we were poor as church mice.

We worked together for a long time. I did eight T. Rex studio albums. Electric Warrior [1981, featuring Get It On and Jeepster] is the one that people should get if they want to hear Marc Bolan at his very best.

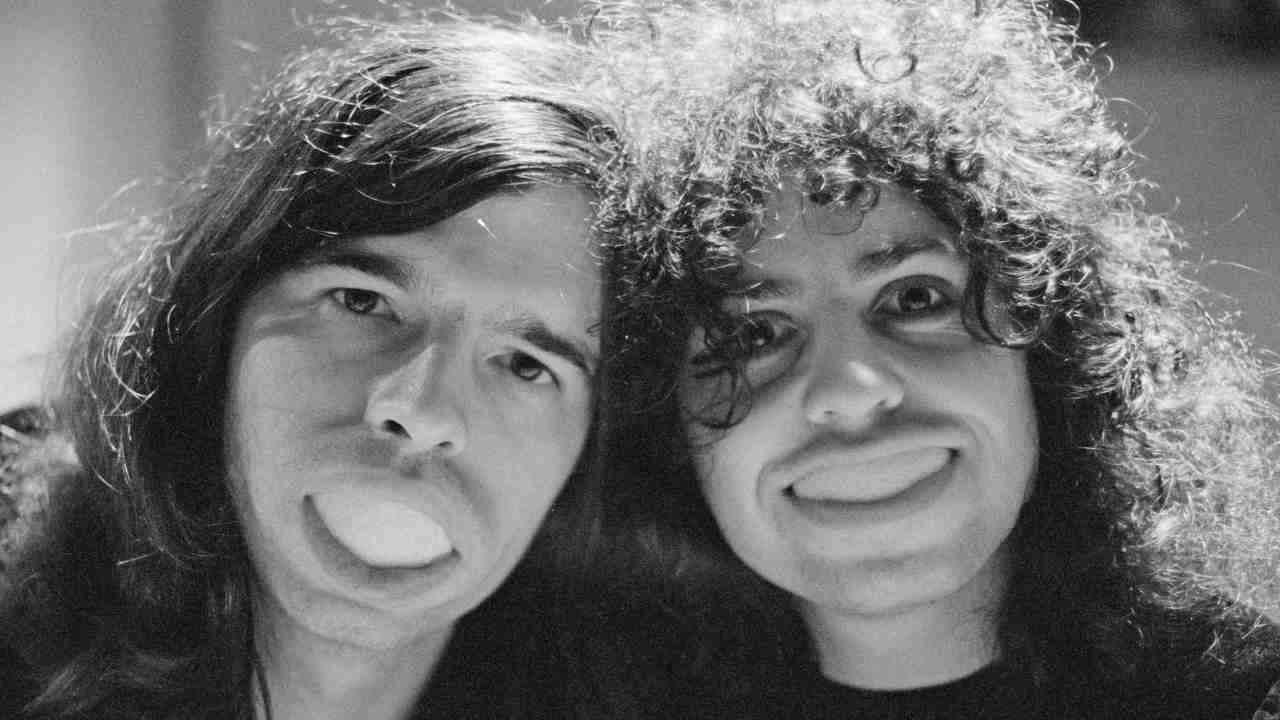

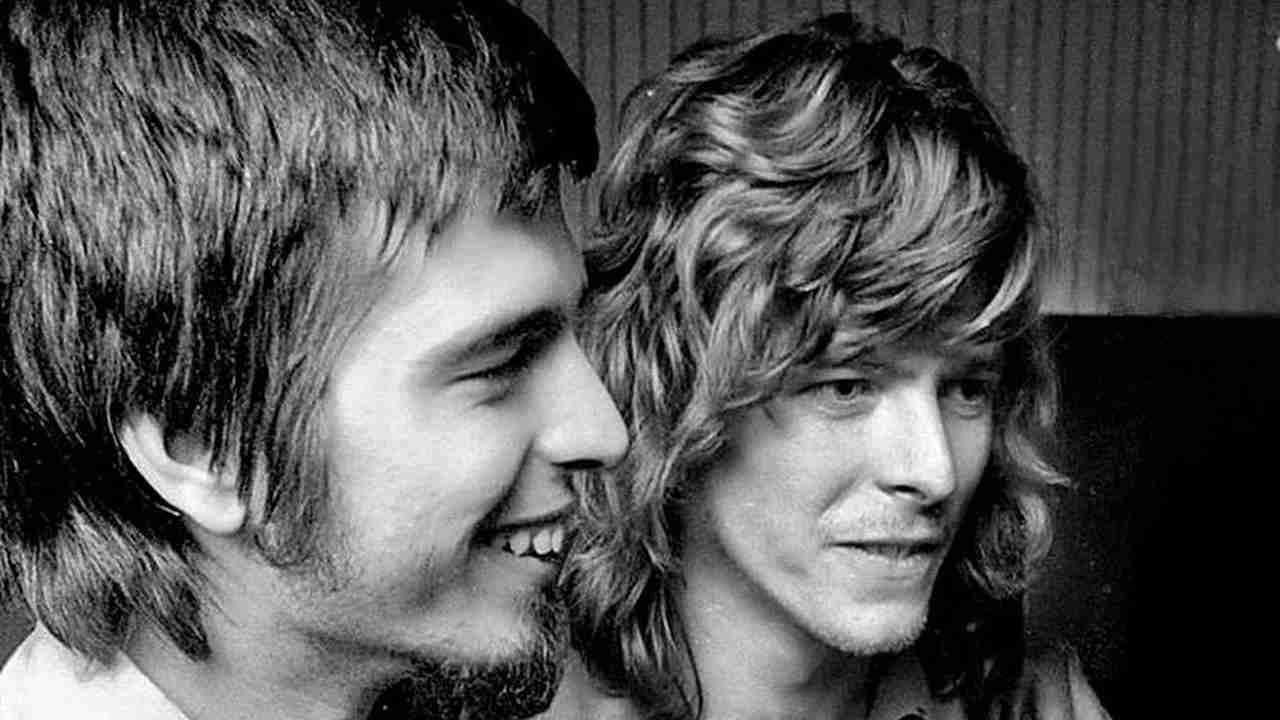

David Bowie

Bowie and I were idealists. We saw our relationship like a friendship, with an arts lab that was part of it. I was very active [with him]. I would be an all-round person to play bass, work the sound, work the lights. We decided that we’d do a much better job if we all lived together so we moved into this big apartment in Beckenham where we lived with our girlfriends, and the band eventually moved in – Mick Ronson and all that. We lived the lives of artists. It was a wonderful time.

The minute I met him I thought he was a special guy. I heard his first album, and I thought the guy was talented even though he lacked direction, and I could hear the star quality in his voice. I was surprised to find out that he was only 19. His personality was very mercurial. A non-stop talker. He was fidgety and very aware of his physical presence. I knew it was going to be a long haul with him, like Marc. Marc gave me the same goose bumps in the beginning.

When Bowie had the Space Oddity thing, I didn’t think it was happening just yet. I thought he had written a very clever song – a novelty record. He had written nothing else like it. We were working on the material for [David Bowie, 1969] and I told him it could very well be a hit, but “you’re going to have a tough time following it up, because it’s not you”. But Mercury had heard the demo and wanted to release it. I didn’t want to record it, so we parted company briefly. I wish I did record it, quite honestly. But we couldn’t follow it up. It was really tough.

What’s lovely about working with Bowie is that he is very flexible, and every time we make a new record he wants to shuffle the deck and do something completely different. It very much started with The Man Who Sold The World, which has since gone platinum, but at the time we couldn’t even recoup the paltry costs of making it. He came into the studio just with sketches and ideas, and yet we had a very strict budget. We had to get that done in four to five weeks. I said: “What are your ideas, can I hear them?” And he said: “Well, we’ll work it out in the studio.” Like the song The Man Who Sold The World: the lyrics and the vocal were recorded and written on the day we mixed it, and that was the last day of recording the album. By then I was pulling my hair out. He still is that way, except now the budget is different.

It could be very disconcerting for people who work with him. He would go through periods using people like Mick Ronson and Aynsley Dunbar, and they’d think they were in the Bowie band. And then all of a sudden he decides he’s never going to use them any more. Even as a producer. I didn’t produce every Bowie album. He would just drop me, go with [Chic’s] Nile Rodgers [for Let’s Dance], for instance. His explanation would be that he just liked to change things. I got easier with it years later after the first time it happened. He’s an artist. He can work with whom he pleases. This is why his sound is so fresh.

The Moody Blues

I’ve produced two-and-a-half Moody Blue albums: The Other Side Of Life [1986], Sur La Mer [1988] and half of Keys Of The Kingdom [1991]. And they are among the most satisfying I’ve ever produced. Back in the 80s, John Lodge and Justin Hayward came to my apartment in London talking about the possibility of recording their new album. They wanted to make something relevant again, as they had done way back when with their symphonic rock using the Mellotron.

I thought the albums were excellent. We had hits, and the fans were obviously still out there, but their record company didn’t really know what to do with them, and treated them as a sort of embarrassment. Keys Of The Kingdom was the album where I learned that the Moodies, like Bowie, liked to shuffle the deck.

Thin Lizzy

After Bowie, a lot of people I worked with were ‘Bowie chasers’. And Phil [Lynott] was one of those. He was always asking how Bowie did this and that.

With the bands and artists I worked with, I saw many varied lifestyles, and Thin Lizzy’s was certainly unique, as I saw when I produced Bad Reputation [1977], Live & Dangerous [1978] and Black Rose [1979]. The 70s was a decade of indulgence. Everyone was living life to the max. It was pre-Aids. It wasn’t only drugs and drinking, sex was also so liberal. Phil had to leave a Thin Lizzy session once to judge a Miss Universe contest, and said he had sex with the winner in the loo afterwards. Whether he did or not, who knows, but when he came back he told his story. Phil was wild and reckless and he paid severely for it.

Phil was one of the greatest frontmen I’ve ever worked with – dare I say a legend? One of the best and last of his kind.

U2

That was a strange one. I got a call from Bono, saying that Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois were trying to edit A Sort Of Homecoming. They said it was going down well live and they thought it could be the next single, but every which way they cut it they couldn’t make a cohesive single out of it. The album version is about seven minutes long. So I told Bono: “The problem is that you don’t repeat something often enough to call it a chorus and your sections of the song aren’t well defined.” He asked me to record them doing it live as it had much more energy. I suggested teaching them a new arrangement for it and he was totally open to that. We went into a rehearsal studio and I reconstructed the song and the guys learned it that way. Then we recorded it live on the U2 1984 UK tour. The sad thing was that I never got a job with them after that. They went back to Lanois.

Sparks

By the time they came along I already had hits and these people were phoning me. They already had a hit with This Town Ain’t Big Enough For The Both Of Us. I loved that record. At the time, it was up there with Bohemian Rhapsody for me.

They were the sort of band that attracted me. I knew I could do lots of interesting and clever stuff with them, and also make hits. They wanted Indiscreet [1975] to be a more experimental album, and we worked mainly in my home studio to achieve that. Every track had a different sort of identity. Russell and Ron [Mael] were unique and funny guys.

Gentle Giant

Gentle Giant were made for me. As a student of music their allusions to Bach, Brahms and Bartok fused with jazz and rock were extremely appealing. I am really fond of the two albums we made together – Gentle Giant [1971] and Acquiring The Taste [1972] – but sales of both albums were pretty mediocre. The second album at least got their cult status. Gentle Giant never had a hit but I have been amazed by just how many people have brought them up in the course of a musical conversation. Those albums are a real feather in my cap. I’m very proud of the two albums we made together.

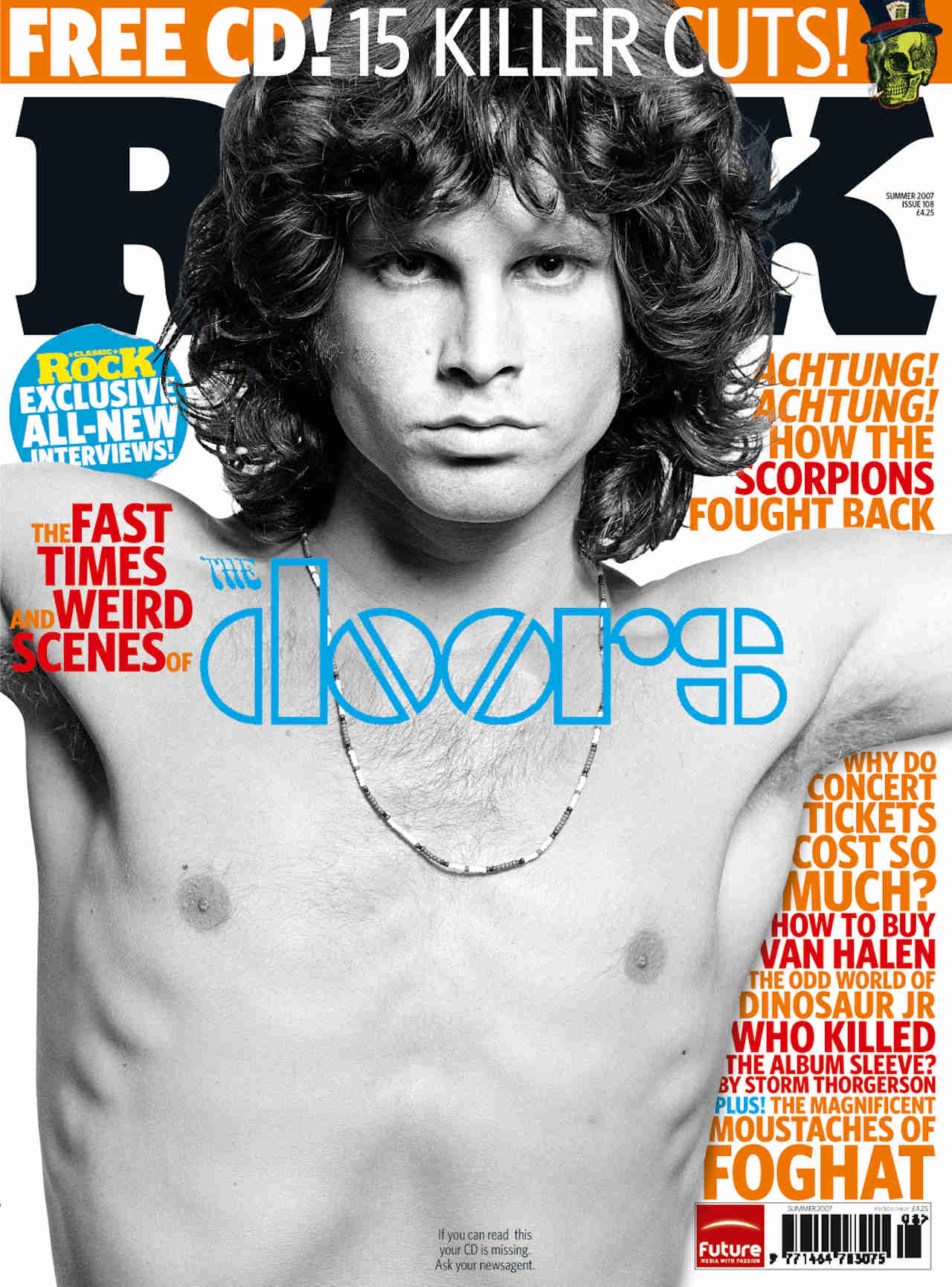

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 108. June 2007