"Lemmy was a creature of habit; he'd have a huge line of speed and then a big fry-up for breakfast": Topper Headon's wild tales of Johnny Thunders, Keith Moon, Keith Richards and more

Living with Lemmy, Sharing a tour bus with Bo Diddley, refusing to get out of bed for Martin Scorsese – these are the stories of Topper Headon, legendary drummer with The Clash

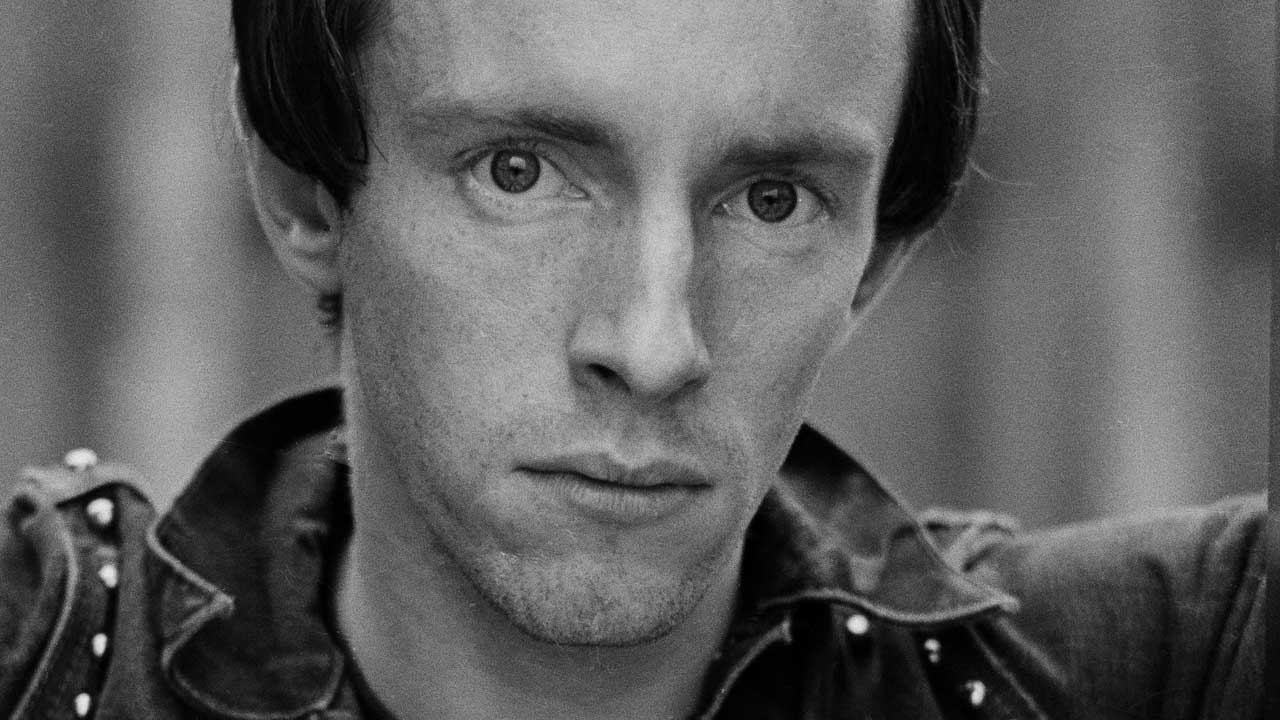

Regarded by some as the most musically talented member of The Clash, Nick ‘Topper’ Headon certainly made his mark with the band when he co-wrote and played drums, piano and bass guitar on one of the band’s most enduring hits: Rock The Casbah.

Having overcome the long-term struggle with heroin addiction which led to his expulsion from the band, Headon returned to his hometown of Dover, where he launched a Narcotics Anonymous group and worked with the homeless charity Porchlight. He was most recently spotted onstage with Ian Dury's old band, The Blockheads.

Captain Beefheart

The Clash were in Los Angeles and I met this drummer who I got friendly with. By now The Clash were getting well known, and wherever we played musicians and various interesting characters would seek us out. So this drummer, I’ve forgotten his name, was playing with Captain Beefheart, who to me was a legend. And he says: “We’re rehearsing at my house. Do you want to come and watch?”

I went over and watched the band rehearse and then had a little jam with them, and then Captain Beefheart walked in. I was wearing a black suit, black trilby with a pink shirt, and a pink handkerchief in the jacket pocket. And he walked over to me and said: “Black and pink, man, that’s cool,” and then he started singing.

Bo Diddley

Bo Diddley toured with us and we really hit it off; we travelled on the bus together. He used to watch us from the side of the stage; he always encouraged me and gave me a nod when I played a good fill. He also paid me an amazing compliment: he said I was the only white drummer that could play his beats.

He’d get on the bus and put his guitar to bed on the bunk and then he would sleep upright in a chair, so if there was ever a crash, the guitar would be safe. I was doing loads of coke and we’d sit up all night. Bo would be drinking rye whiskey and telling me all these amazing stories. He’d have a different pick-up band in every town he played in. I did one gig with him. Joe [Strummer] used to introduce him as one of the people we adored and a big influence. We wanted to show the audiences where our music had come from.

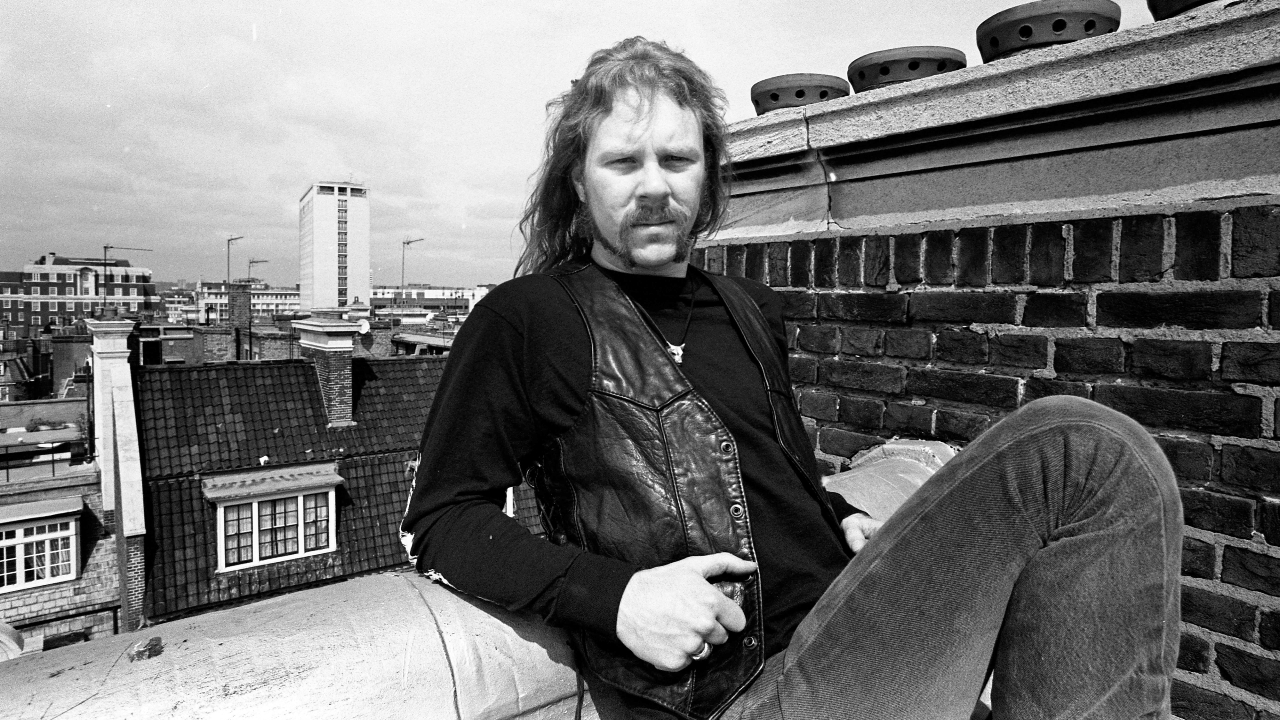

Lemmy

We lived together for a while. He had a house in Coleville Terrace just off Portobello Road. [Motörhead drummer] Philthy Taylor had a room in the house and had moved out, so I moved in. Lemmy was… well, he sleeps with his eyes open. It was a horrible place, just like a squat. I just indulged with Lemmy, taking speed and stuff.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

One day I asked him for a line and he stuck his knife out with a pile of sulphate on the end of it. I bent over to take a snort and almost sliced my nose in half. There was blood everywhere. Lemmy was a creature of habit; he would always do the same thing when he got up in the morning: have a huge line of speed, and then a big fry-up for breakfast. He was one of those people who took drugs to keep himself normal.

Guy Stevens

I loved Guy Stevens [The Clash’s producer]. He was so out there. It was sad, really, because he was a chronic alcoholic. He turned me on to hemeneverin [medication used to treat alcoholics].

We were recording in Essex, and one day Guy appears with someone who we thought was his mate. The session went on all day long; it started about two in the afternoon and it went on until the early hours of the next morning. Guy was drunk as usual, but it was a good session and at the end of it. It turned out his ‘mate’ wasn’t his mate, it was the cab driver. And Guy’s bill was horrendous. Guy must have just said: “Come and see what I do, I’ll pay the meter.” The guy must have been made up to be in a recording studio where history is being made – and the cab’s being paid for.

By the time we worked with Guy he had nothing. We made demos for London Calling, and we had to go out and get a beat box for him because he had nothing to play them on. He was living with his mum. But Guy was incredible to work with. Between him, Mick Jones and Bill Price [engineer] they made it magical. And Guy didn’t really do anything.

There was one time we were recording a backing track, and we looked up through the window into the mixing room and Guy and Bill Price were fighting. Guy had been asleep under the mixing desk, unconscious – and this is the record producer! And suddenly he shouts up to Bill: “Don’t touch the bass!” Bill just carries on, obviously moves the bass. So Guy grabs him by the legs and they start wrestling. Bill’s trying to hold the fader where it is and Guy’s trying to push it down. The four of us stop playing and we’re looking at our record producer and engineer having a fight.

One time, Joe’s playing piano and he says: “I want to put piano on this.” And Guy says no. Joe keeps insisting. So Guy just pours a bottle of wine into the piano. That was about four grand’s worth of damage.

He used to swing ladders around the studio. There’s one bit on London Calling where if you listen to it carefully you can hear a thud in the background where Guy’s pulled a stack of plastic chairs on top of himself. He kept things alive.

Johnny Thunders

I loved Johnny Thunders because he was the same height as me [laughs]. When I stayed in New York I was up to all sorts of stuff with Thunders. One day we were sitting in a cab round the back of a building waiting to score, and this girl I was with said: “Look, I know Johnny, and if I was you I’d go to round to the front of the building.”

So I got the cab driver to drive round. And who was coming out the door, running? Johnny. He was doing a runner with my gear. I said: “Johnny!” He went: “Ahhh!” and got back in the cab. If we hadn’t gone round the block he would have been off down the road. But that was Johnny. He was my favourite New York Doll.

Keith Moon

Paul McCartney was having a launch at the Peppermint Lounge in London. I was in the bar and I spotted Keith Moon. He was a hero of mine since I was a young lad. I’ve always tried to incorporate elements of his style into my playing. Anyway, I was introduced to him and he was really friendly. He was very lively; out of his head but really sociable – like you’d imagine Keith Moon to be, buzzing around everyone.

The next morning I put the television on and saw that he’d died, and that made the whole experience really surreal. No one had ever played drums like him and they haven’t since. I also loved all the stories about him. Another bonus from the meeting was that Keith had heard of The Clash, as Pete Townshend had played a gig with us in Brighton. And that was another amazing experience: to look up and see Pete Townshend standing on your drum riser, flailing his arm.

Keith Richards

I was at Studio 54 and I saw Charlie Watts sitting in the corner quietly drinking a beer. I went up to him and introduced myself, and he said “sit down” and we started having a chat about drumming, The Stones and The Clash. Then Keith Richards shows up with a couple of security guards either side of him, who were less security and more holding him up. Charlie goes: “Oi, Keith! Topper’s here from The Clash.”

So Keith comes lurching over, trips and puts his arm on my shoulder to steady himself . This photographer who was hanging around takes a picture, and it looks like we're long-lost buddies. I wish I still had that photo. I know it sounds corny, but these people were my heroes and it meant a lot to me that it looked like I was really buddy-buddy with Keith, when the reality was that he could hardly stand up [laughs].

Martin Scorsese

We were recording Sandinista! in New York and Scorsese was working on Gangs Of New York [Topper is mistaken: Sandinista! was recorded in 1980, and Gangs was made in 2002. Scorsese would have been making Raging Bull at that time – Ed.], and he really wanted to use some of our stuff. He also wanted us to appear as a gang in The King Of Comedy but I’d been on the razzle the night before and refused to get up. [The rest of the band did appear, credited as 'Street Scum'.]

Joe Strummer

The Clash were playing in Norway, and it was the middle of summer when it’s light 24/7. Me and Joe were up all night drinking in his room and he passed out. Joe was a vegetarian, right? So I put a couple of slices of salami over his eyes, and then got his passport and drew a moustache and a beard on his photo with green felt-tip pen and left him there.

The next day we flew to West Germany – and this was about the time of the Baader-Meinhof, so security was really strict. Joe went to the front of the queue at check-in and handed his passport over. The guy just looked up really furious. And Joe didn’t know what the fuck he was looking at. The guy showed him the passport, and Joe knew straight away who’d done it.

We had a laugh about it. And the next time Joe went through customs he got some green tape and gave himself a green moustache and beard, so when the guy looked up Joe looked just like the picture in the passport.

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock issue 124 (October 2008)

Pete Makowski joined Sounds music weekly aged 15 as a messenger boy, and was soon reviewing albums and doing interviews with his favourite bands. He also wrote for Kerrang!, Soundcheck, Metal Hammer and This Is Rock, and was a press officer for Black Sabbath, Hawkwind, Motörhead, the New York Dolls and more. Sounds Editor Geoff Barton introduced Makowski to photographer Ross Halfin with the words, “You’ll be bad for each other,” creating a partnership that spanned three decades. Halfin and Makowski worked on dozens of articles for Classic Rock in the 00-10s, bringing back stories that crackled with humour and insight. Pete died in November 2021.

- Fraser LewryOnline Editor, Classic Rock