Whenever he’s going out in the car, it’s Rick Wakeman’s habit to grab a handful of CDs so he’s got something to listen it while he drives. Not knowing which albums happen to be in the pile he’s snatched up adds a nice element of surprise on the journey, kind of like shuffle play, but with the addition of the internal combustion engine.

On a recent jaunt, Wakeman found himself listening to Close To The Edge. “I hadn’t heard it for a long time and as I was listening, I actually pulled the car over on the A14 and I sat there, and I actually said out loud, pardon the language, ‘How the fuck did we do that?’ Because when I listen to it, with the technology we had at that time there is no way we should have been able to do that album. Absolutely no way.”

As Wakeman talks about the album he was a part of 50 years ago, he sounds genuinely moved. “We had ideas of what we wanted to do and then we had to sit down and figure out how to do it and record it. That was the genius of that album and I put it down as the very last Yes album where we were completely ahead of technology. For me, what makes Close To The Edge the finest Yes album is [that] it’s where every single one of us were into it and knew what we were all trying to achieve.”

There are some musicians who will quietly tell you that they really can’t remember much about some of the albums they’ve made. There are lots of reasons for that of course. Too much rock’n’roll lifestyle back in the day will seriously curtail the grey matter’s ability to dial up events, and to be fair, the people who were all in their 20s and are now in their 70s probably weren’t taking notes at the time on the off chance that someone would be asking them questions about what they were doing 50 years ago. Yet for Rick Wakeman, who admits he was no stranger to many indulgences as a young man, the events of those times at Advision Studios remain surprisingly fresh in his mind.

“I can tell you exactly what a typical day during the making of Close To The Edge looked like. I used to come in and park outside the studio at about 10am There was a little snack shop café on the corner of Gosfield Street and I’d go in and get a bite to eat. When I went into the studio they were making coffee and Steve [Howe] was there – he would spend a considerable amount of time tuning his guitars and getting ready for whatever he wanted to do.

"Then Bill [Bruford] would turn up saying that there was no point in turning up beforehand as Chris [Squire] wouldn’t be there, which of course he wasn’t. Jon [Anderson] would arrive and he and I, or Steve and him, might go into a room and talk about what we were going to go through that day. Eventually, early afternoon, Chris would show up after having just rolled out of bed. It was a nightmare but you had to live with it. Bless him, to his dying day his time-keeping was crap. Chris would then sort of play around with his bass and then if we were lucky, by mid-afternoon, we might actually play something.”

In 1971, the year before they recorded Close To The Edge, Yes had undergone two important changes in personnel. This was not about finding mere substitutes to continue along a particular path. Injecting new talent as a matter of policy would always triumph over sentiment. In those early years it was indicative of a ruthless pragmatism that at its best sought to ensure Yes’ reach would always exceed their grasp, striving to always transform and improve rather than settle for the ordinary or average.

By actively embracing change and taking the difficult decision to part company with original members Peter Banks and Tony Kaye, Jon Anderson, Chris Squire, and Bill Bruford were making a deep commitment to what Yes might become rather than what it was. The influx of adrenaline and creative energies accompanying such decisions didn’t just raise their individual game as players but formed the impetus that would put the band in a position where it would not only survive but evolve, grow and hopefully prosper.

Steve Howe’s impact on the band on The Yes Album was nothing less than seismic, shaking their sound from top to bottom with a galloping virtuosity that bordered on the rapacious, greedily swallowing any and all challenges with relish as they rushed toward him. His debut was the very definition of hitting the ground running. Wakeman’s arrival shortly afterwards was every bit as significant. That he could replicate his talented predecessor’s work was a given.

However, his real value was in his ability to remodel the base metal that accrued in the Yes rehearsal room and writing sessions; there were numerous riffs, runs and sequences that all needed to be honed and threaded together. His formal musical background allied to his experience as an in-demand session player, where efficiency and speed went hand in hand, meant he quickly understood why one thing worked over another without the need to laboriously engage in a process of elimination.

Within a few minutes of listening to something, Wakeman was able to explain or demonstrate what might be possible, where something might go. While there was sometimes an inherent value in sifting through what amounted to trial and error, he helped speed up proceedings in a way that the band had, until then, all too rarely encountered. Between the two of them, the new members embodied a technique that could be either as surgical or as flamboyant as the moment demanded.

Both also brought with them a masterly grasp of texture and dynamics, an element that had been front and centre on the multifaceted showcasing that was Fragile. With these two parts of the jigsaw now locked firmly in place, Yes seemed capable of anything. As novelist Paul Auster once put it, “If you’re not ready for everything, you’re not ready for anything.”

It’s a line that perfectly describes the point at which the group found itself in 1972 as they entered Advision Studios to begin work on Close To The Edge.

Given Fragile’s success it would have been very easy for Yes to have pursued what was obviously a winning formula. There’s no doubt that wasn’t something Anderson was prepared to countenance. The point was to keep moving, keep expanding, keep developing. In common with other groups of the era, the notion of keeping things in the neat and tidy furrows of three-minute pop songs or prolonged bluesy grandstanding wasn’t where the juice was. In the days before progressive rock became a broad-brush genre description, it was perhaps a goal, a route to an artistic state of being.

Yes were always on the lookout for ideas that could be incorporated and adapted into their musical vocabulary and the development of Close To The Edge was leavened by many encounters and experiences. One example of this filtering process in action happened during their US tour during November and December 1971, where on some dates they were supporting The Kinks, whose criminally underrated Muswell Hillbillies had just been released.

However, the new record was largely ignored in favour of a crowd-pleaser setlist that included a smattering of 1960s numbers including the beautiful, elegiac Waterloo Sunset, originally released in 1967. Just four years separates Ray Davies’ sublimely bittersweet love song and Yes’ setlist, which leaned heavily into The Yes Album and Fragile. Yet the pairing of these two bands at opposite ends of the rock continuum demonstrates how fast the pace of change and experimentation in form and content had moved.

While acknowledging the observational acuity and melodic brilliance of Davies’ songwriting, in comparison the sharp differences between the two groups made it seem as though Yes had beamed down from some far-flung future.

However, that contrast was made all the more stark on November 28, 1971 when a third act was booked to support Yes and The Kinks at the State University of New York in Stony Brook, NY. The Mahavishnu Orchestra had just released their debut album, The Inner Mounting Flame, and had been placed on the college circuit as a way of moving beyond the wholly unsuitable jazz clubs where they had begun.

If Yes made music from the future, then the sonic assault of Mahavishnu Orchestra, led by John McLaughlin’s blisteringly fast lead guitar, appeared to be coming from another galaxy entirely. As Squire and Anderson watched from the wings, the singer turned to the bassist and with his jaw still slack from what he was hearing said, “Chris, we’ve got to start practising.”

They always knew that after Fragile they were going to undertake a long-form piece. At a little over 10 minutes, Heart Of The Sunrise was the dry run, bringing together contrasting flavours and sections. Such an idea wasn’t new of course. Bands including Van der Graaf Generator, Caravan, Pink Floyd, ELP and Jethro Tull, to name but a few, had all got there before them but the yearning for that elusive symphonic statement had been on Yes’ to-do list almost from the beginning.

Early in their career, they’d leaned toward the grand or epic, be it through startlingly reimagined cover versions, the addition of an orchestra, and through their own original material. Success wasn’t always guaranteed, but the fact that they had been stretching their compositional chops in the process meant that when the time came they were more than warmed up. Given Fragile’s success it would have been easy for Yes to have carried on doing what they were doing. But with ambition spiralling high, that jut wasn’t on the agenda.

Steve Howe also witnessed the show and was similarly impressed by what he saw and heard. Six months later in Advision Studios, as they worked on Close To The Edge, Howe channelled some of the creative sparks he’d seen flying that night from McLaughlin’s twin-necked Gibson into his own playing on the astonishing guitar solo that leads the opening of the title track.

“Jon and I had basically dreamed up the concept that primarily this song needed a lot more space. It had the unusual intro, it had all these ingredients. And we pretty much mapped them out,” he explains. “We’d discussed how we wanted to open the album. On Fragile there had been the acoustic harmonic that began Roundabout and here we thought: what would be the most unusual intro you could have? How about a Mahavishnu Orchestra-style intro?

"Jon and I were really in awe of John McLaughlin’s great band and we thought we’d hurtle in with something like that and just surprise everybody with high tempo and lots of movement. So, as a guitarist, I could grab certain ideas for the opening like the leaping between the octaves. I knew that was how I was going to start.”

Whatever shortcomings Jon Anderson may have had as an instrumentalist, he was able to visualise the shape and structures into which the band would fit and make their own. “I was always aware of where we were heading structurally. I was listening to a lot of classical music while touring and Sibelius’ Fifth Symphony [Symphony No.5] I liked. The structure of the symphony actually mirrors the album as a whole,” Anderson explains. “It’s got a very wild first movement, a gentle second, and the third movement is very majestic. I thought the band could get into performing with that sort of musical positioning.”

Another influence on his thinking was the then-recently released Sonic Seasonings, a double album by Wendy Carlos comprising four side-long suites, brimming with evocative Moog-created ambient environments. Anderson discussed with engineer Eddy Offord how they might come up with something similar. “I wanted to create this sense of energy or a force field before the band started, and then have the group climb out of it with a wild and crazy solo section, raving away as though we didn’t know where we were going. You’d get to a certain point and you’re going to stop dead and a very straight choral thing would come in and then the band would carry on again.”

Under Anderson’s direction, the swirl of tape loops featuring speeded up keyboards and other electronic textures created an impression of a humid jungle streaked with exotic beasts and birds, creating a distinct world of its own. The surging velocity of that opening section remains one of Yes’ stand-out moments in a catalogue bursting with adventurous instrumental passages. The vivid, cartwheeling guitar solo bristling with all kinds of barbs and jagged edges is certainly a high point in Howe’s long career. “Chris Squire was always a great one for saying, ‘Steve if you want to improvise, we need a good structure.’ So, there’s a lot of movement in those chord structures that move around.”

Howe recalls that when it came down to rehearsals prior to the recording of the solo he had some assistance from Anderson. “Jon was great sitting there being the singer. He couldn’t play these fast riffs but he could strum on his guitar and make suggestions: ‘How about this key for that bit?’ or ‘How about down here?’ I give due credit to the arrangement skills that we had on the collaborative level. When we were together we could arrange stuff though sometimes we’d forget the arrangement the next day and we’d scratch our heads and wonder what we did,” laughs Howe. “So in the end we recorded most rehearsals on a cassette. Can you imagine trying to listen to all that noise of us all playing in a room? It was a nightmare. But we could still discern what the structure was and what the idea was. So we kept looping it day by day in rehearsals and then we’d look at all the material we could put on the album. That was our skill: fine-tuning arrangements in order to develop something rough into something polished.”

Close To The Edge became a repository for a variety of half-formed ideas that in some cases had been around for a while. A descending guitar line that had previously existed as part of the song Black Leather Gloves in Howe’s pre-Yes outfit, Bodast, was now repurposed for Total Mass Retain.

“You tend to have plenty of ideas and sketches, which don’t necessarily have a home, so you pitch them in,” says Howe. “Jon and I worked like that all the time. One of my songs had the line, ‘Close to the edge, down by a river’, which actually referred to where I was living at the time, next to the Thames.” When Anderson heard the phrase, the symbolism of the river immediately connected to metaphors within Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha, which he’d been reading at the time.

“The river leads you to the ocean, all the paths lead you to the divine. So the idea was that as human beings we are close to the edge – the edge of realisation,” explains Anderson. This connection of ideas was typical of how Anderson worked, says Howe. “He always did this. He’d take an idea of mine but then he’d set it into a different global sensibility. It wasn’t just the River Thames but now the referencing of being close to the edge of some kind of enlightenment.”

Anderson recalls Howe presenting what was, in essence, a humble love song whose opening line was, ‘In her white lace…’ but immediately began a counter-melody off the top of his head. “When I started singing, ‘Two million people barely satisfied’ I had in my in mind what was happening around the world, starvation in African countries. So many people lived so well while so many people didn’t. I get high and low on the whole concept of life – ‘I get up, I get down’. So it worked out that Steve and Chris sang that while I sang my melody over these exact same chords. It was magical… it just happened.”

Divining the precise meaning of a lyric isn’t important, argues Howe. “There’s often a reluctance on the part of songwriters, and I think it’s a good thing to be reluctant in this regard, to describe exactly what the song is about. It’s very important to write your lyrics the way you want to and then not have to explain them. But I think the ethereal quality was something I got more and more into with lyrics in the last 30 years than I was maybe 50 years ago and I could see what Jon was up to and there were messages hidden in the songs that would somehow resonate with us.

Jon took a lot of grief sometimes about his lyrics and sometimes I did as well with mine but neither us cared. This is what it is. A lot of people did relate to the sense of there being a wider, broader, more spiritual [side] to the lyrics. Music is a mystery that we’re all part of. The listener is in that mysterious place, but so is the musician.”

The spiritual aspect discerned within the track and elsewhere in the band’s output is something Wakeman recognises and has an affinity with. “The majority of Yes music that I’ve been involved with, certainly in the 70s, did have a very spiritual element to it and I think all of us in our own ways had different spiritual thoughts, beliefs and standards and what have you, but it all worked for all of us in our own way. I think that when you’re playing music you get a feeling that there’s something more than just a load of notes thrown together. There’s something about this record, maybe Going For The One might be the other one, where I felt we were all of us singing from the same hymn book.”

The cathedral-like ambience of I Get Up I Get Down is fully exploited with the arrival of Wakeman’s majestic pipe organ recorded at London’s St Giles-without-Cripplegate, where he’d already recorded the parts for Jane Seymour from his solo album, The Six Wives Of Henry VIII, released the following year in 1973.

“The church organ part wasn’t easy to do," he says. "The recording itself in the church was fine because I had the tempos. We set up a Revox tape recorder and the mics and it went fine. The hard part was back at Advision Studios. I mean, you couldn’t just drop it in. It had to be absolutely in at the right place. So it was a matter of running it along with the master track and having various attempts at trying to slot it in, which we eventually did.”

The startling Moog line that corkscrews into the piece not only breaks the spell of reverence and rapture but re-establishes the connection to the harsher instrumentation heard in the earlier sections.

“It was always planned that coming out of that, we needed to get back into electronic instruments again,” Wakeman continues. “So at the end of the church organ you would have the Hammond solo. That was quite a delicate operation to make sure the Hammond didn’t sound weak or the organ didn’t sound weird.” It could have sounded abrupt and unconvincing, he says, but it sounds like a genuine development. “The great thing about the actual track, Close To The Edge, is it has some brilliant natural progressions within it.”

Anderson’s impassioned performance makes for an electrifying experience throughout but especially over the build in the finale of The Seasons Of Man section. There’s an excitement that borders on the exultant in the voice that sings, ‘Now that it’s all over and done, called to the seed, right to the sun, now that you find, now that you’re whole.’ It’s an outstanding moment and a favourite for most members of the band.

“That big end section, that’s that place where it’s like we’re climbing the mountain, you get there and you sit back and take in the view. My head was spinning every time I listened to it or sang it,” comments Anderson with more than a hint of wonder in his voice. His vocal achievements here are still admired by Steve Howe. “To this day I think how Jon sung it originally in the studio in G minor is just amazing. When we started touring it we had to drop that end section a tone below in F.”

While Steve Howe is well-known for his insistence on having the time to find the correct tone or guitar within a piece, he readily admits he was not alone in this regard. “Chris was really picky about his bass. I can’t remember how much bass he overdubbed. We might get a track down and Chris would still not be happy with a part of it. So that same day before the equipment was broken down he might fix something or play something better or change his part somewhere.

"He was usually the last person to get his part down. He liked coming in after everyone else so he could hear the whole song and say to himself, ‘I think I could play better here’ or ‘That doesn’t work there I’ve got to change it up.’

“Sometimes Chris would go to great lengths to perfect something and it was conditional on how he was feeling or if he could get it cut in there, or maybe he’d say, ‘I’m not going to get this in and I’ll do it afterward.’ He had a tendency to overrun on some of it. I remember that more on Drama because it’s years later and Chris was in there doing one of those fast runs we had. He was doing it all evening and I wondered why. But it was just Chris’ way. He wasn’t really an improviser. He had to have his parts in his mind and he had to get them right and they were really good parts and worth waiting for, but it could be a long wait.”

Wakeman elaborates on why Squire’s approach could be a source of much frustration and tension. “Chris would play and then want to redo the whole thing. We’d go, ‘But we’re happy with what we played.’ So he’d fuss around and redo everything and often, his original was kept because it was better. Chris always felt there was a better take to be had and I suppose it was a great attitude to have, except he wasn’t right. So then, I’d go up to the pub around the corner and come back at 10 or 11 and Chris is still doing his bass part again with Steve and Jon trying to egg him on.”

During the making of the album there were inevitably many late-night sessions, though these were often of little to no value when they listened to them the next day, as Wakeman explains. “We’d come in in the morning and have a listen to the board mix of what we’d done the previous night and it would be useless, the hi-hat would be shrill and deafening and so on because the more you do in a day, the top end of your hearing tends to drop. So what you do is you keep winding the top end up. So nothing was ever any good. David Bowie never, ever worked late at night because he said it doesn’t work. Fresh ears in the morning, always the best.”

Recorded in sections, sometimes a bar or two at a time, these were then sifted and their merits assessed before each section was then painstakingly sewn together in an arrangement, rather like an ornate patchwork quilt. Only at the end of the time-consuming process were they then able to see the full picture. Even then it still required edits and overdubs before it was finally mixed. Making the album was likened by Bill Bruford as like having five people trying to write a novel together.

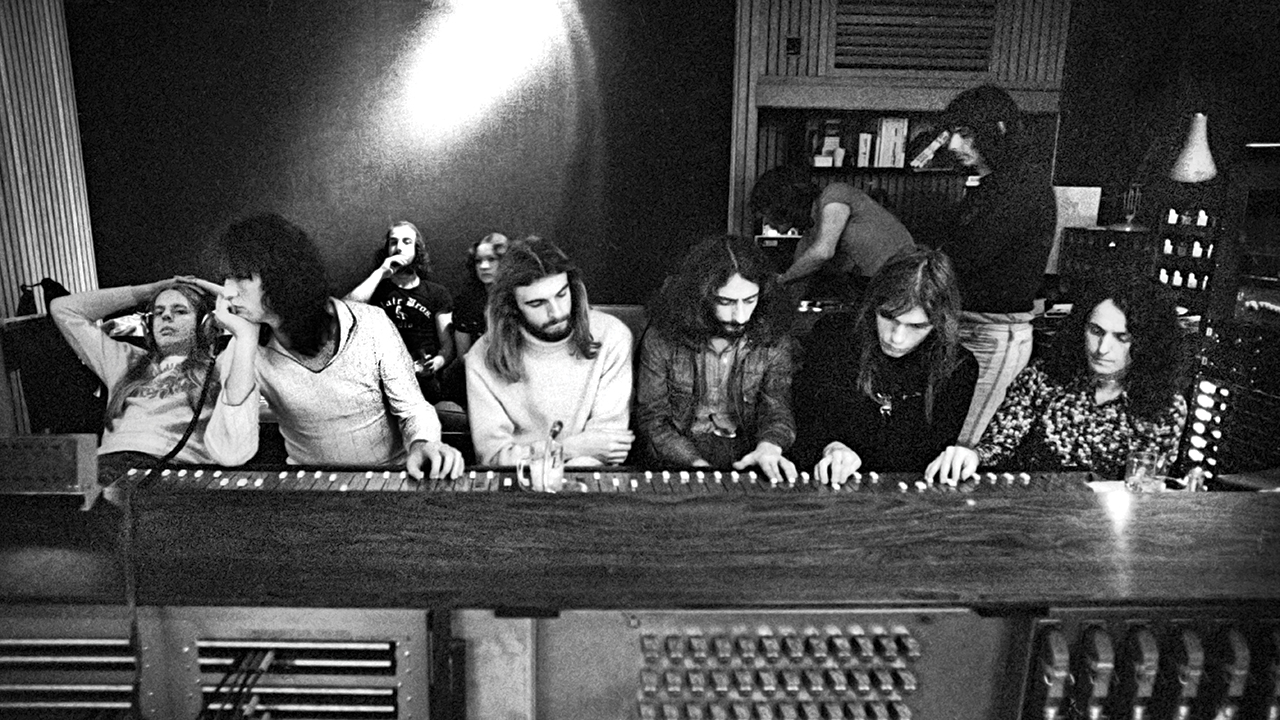

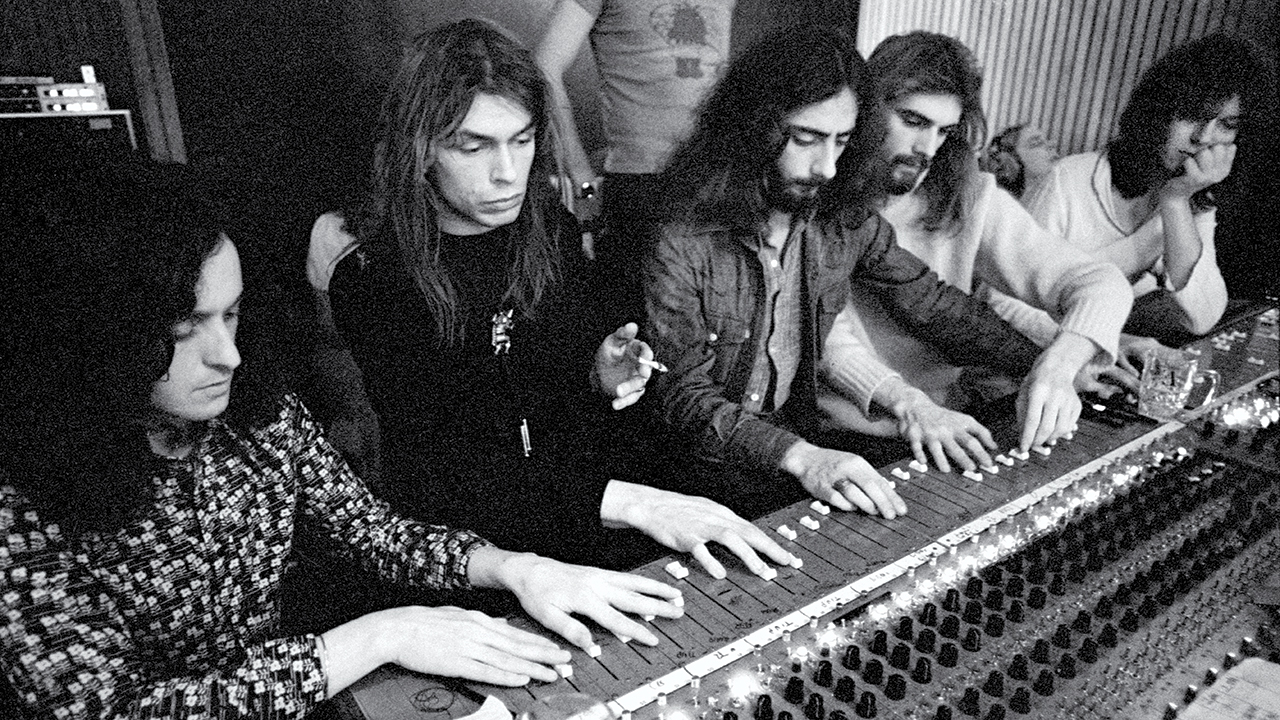

As torturous as that was, after all the haggling over which bits or sections worked best next to one another and which parts should be thrown out, the mixing process itself was another challenge. In these days of automated on-screen faders getting the balance on individual instruments is a relatively civilised affair. In Advision, and every other studio at the time, it was a case of all hands to the desk as several members of the group simultaneously clustered around banks of faders and controls following a kind of aural shooting script when it came to bringing takes in or out.

One might assume that camaraderie and team spirit would be a by-product of this work but often it was just the opposite. “From day one, I loved the way that we wrote, I loved the way that we recorded, but I hated the way we mixed,” says Wakeman darkly. “I think it was a hard job for Eddy Offord. We didn’t get the width we should have had in the mixes and that was because he’d more often than not have 12 hands on the faders and lots of knob twiddling and God knows what. At the end of the day it got so compressed it didn’t matter who pressed or twiddled what. Everyone was listening only to their own part and not the overall thing, not thinking about the finished product.”

Sounding rather rueful, he says this was always a problem in Yes. “I was from a different school of how you mix. The person I learned the most from was David Bowie and his various producers. I worked with Ken Scott, Gus Dudgeon and Tony Visconti, and David Bowie had it spot on: he never went to any mixes. What he did [was] he would go away, leave them to get on with it. He could trust them, they knew what he wanted to do and when he listened to it afterward, that was the closest he could get to hearing the music for the first time. That’s what I’ve always done and I wish Yes had done that. But I don’t think we ever had – no disrespect to Eddy Offord – I don’t think we had somebody we all felt we could 100 per cent trust to get what we wanted.”

Yet despite the tensions that come from five individuals working through their respective idiosyncrasies, the finished results on the completed album were exceptional then and it remains so now. Not only had Yes ticked their long-held desire to do an extended suite occupying all of one side, and achieved it without any gratuitous padding, they served up two other tracks that also stand up as a superb examples of what progressive rock was about. If he was certain about the shape of the title track, Yes’ principal animateur Anderson was less certain about And You And I. “I’d written this very simple song,” he recalls, “but we got to a certain point where I said we had to create a theme, somehow it had to get bigger.”

It was exactly why they needed someone like Wakeman in the room, recalls Bill Bruford. Although there were contributions from all the band, Wakeman’s skills as an arranger and musical fixer were crucial to the track’s grandeur and stately development. Howe’s contribution was no less vital. We hear the 25-year-old man say, “Okay” at the start of side two.

“There’s a kind of honesty to that moment,” agrees Howe. “That song is produced in a whole different way. A lot of time was spent getting that theme right with the right bass and right chords and right key changes. There were endless rehearsals but when we got to the studio and played it, we had to find a way into the song. We were ready to begin, that’s why I said, ‘Okay’ but my rambling harmonics we liked and decided to keep in. Basically, the entire front of the song was performed with me with a metronome.”

Siberian Khatru remains a masterclass in concise, dynamic writing and arranging. Bristling with rapid gears shifts in the tempo, soaring themes, beatific vocals, and even the rush of a harpsichord as each new section builds upon the last the cumulative effect of the piece is dizzying. When, after seven minutes, everything is stripped away, it’s akin to being ushered inside an immense engine room where the pulsating bass throbs and the inner mechanisms of how the band works are briefly exposed as the Bruford-composed cyclical guitar line whirls about, the cogs and wheels of Yes turn in perfect synchronisation.

“We stole a bit from Stravinsky by having that pounding staccato pounding and at the same time throwing those accents on voice and drums and having me driving through it with that constant guitar motif. It’s a good example of hi-tech arranging circa 1972,” says Howe. When the entire band kicks back in, there’s an extra exhilaration in Squire’s ascending basslines. However long it may have taken to get that best take, it was worth every minute.

The gleaming triumph of Close To The Edge was tarnished for some by Bruford’s decision to leave and join what would become the Larks’ Tongues In Aspic line-up of King Crimson. As far as Bruford recalls, there was no big meeting of the band, no big announcement where it was formally announced like an election result. “I seem to remember long conversations in my flat in Harcourt Terrace, Fulham. I knew leaving would cause an upset.

"I was terrifically flattered and gratified that they wanted me to stay, but on the other hand, Jon understood exactly that people have to do what they have to do. He took the artistic line, which was very sweet of him. He was lovely about it. ‘You must do what you must do. We’re very sad, it’s been fantastic, but if you have to do this, then go ahead.’ I think for a long time Chris probably thought that I’d been spirited off by Robert [Fripp] and over-influenced by him.”

In the 50 years since the album was released, countless legions have admired the economy and grace of Bill Bruford’s playing on it. Howe counts himself in that number and thinks Bill’s sound is a key factor in making the album a musically coherent statement.

For someone who has come to have such a major impact on drummers, other instrumentalists and fans alike, Bruford’s instantly recognisable playing does not actually occupy that big a space, says Howe. “If he’s hitting drums and crashing cymbals all the time that’s going to wipe out a lot of the frequencies that somebody else wants to enter into. He didn’t have two bass drums and six Rototoms and so on. He had the basic kit. But the thing was, that was his art. The basic kit is all you need and he made that work in a wonderful way because he didn’t see himself as a rock drummer so much. His drumming is outlandish. It sounds straight 4/4 but you listen to the way he adds that extra snare. That’s Bill’s genius.”

Yes weren’t about to let the small matter of a crucial departure get in the way. With Alan White already a friend of the band and a regular presence at Advision as they worked on the album, he was the obvious choice to help propel Yes on to their next great adventure.

Steve Howe, now 74, and the only member in the current incarnation of Yes to have played on the album, jokingly remarks that as well as playing the pieces on the record for the last 50 years, he’s probably been talking about them for at least that long. Yet he doesn’t regard this as a burden of any kind, he says. “I think everybody that plays on it is very proud of it. It’s a very adventurous record. It’s the first time we did a one-side song and two songs on the other side. I revel in it.

"I’m delighted it’s so popular and so convincingly performed on the original record. It’s always a reference to go back and hear how we did it with the original tempos and everything around it. I think Close To The Edge, And You And I and Siberian Khatru are exceptional indications of a band that reached a certain peak in their creativity.

"There was an argument [that] you’ve always got to try something before you can say no and as we did we’d argue about the merits of the music. But we did allow each other enough space to be happy and, at the end of the day, everybody was happy with Close To The Edge.”

This article originally appeared in issue128 of Prog Magazine.