Breaking America has been on bands’ to-do lists since humankind has twanged guitar strings and air travel has existed, but in certain corners of the music industry, there are concerns that the days of touring the US might be numbered.

For the last five years, rock website Louder Than War has been chronicling the supposed unfairness of the US visa application process, and last October, the site’s founder John Robb started a campaign to make the process easier.

Speaking to Metal Hammer, John explains that his main issue was how complicated it is for British musicians to visit the US, while American musicians can tour the UK with very few issues. “It’s very expensive and time consuming, and there is no set deadline for when the visas arrive,” he says. “You can apply months before and they still get sent to you late, which means tours and flights have to be cancelled. To rub it in, American bands can come to the UK for virtually nothing. We want a set timetable for the process, even if it’s six months with set delivery stages. We would like to see a reduction in the high charges from agents, or even question why we have to use agents.” John estimates that the cost for getting a visa – including agent’s and legal fees – can come to over £5000, while he claims American bands can visit the UK for as little as £30.

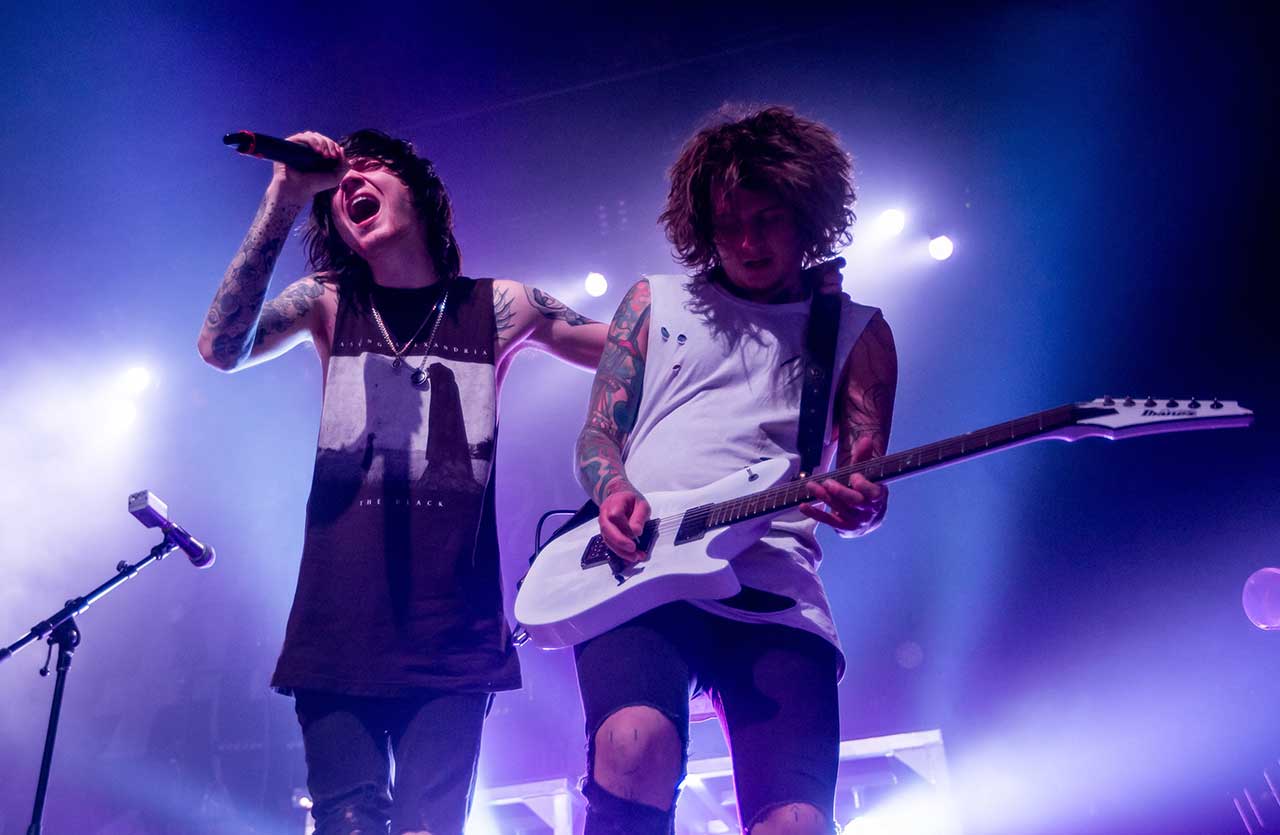

To an outsider, Asking Alexandria’s Ben Bruce might not be in a position to complain. He’s toured or played at major festivals in the US no less than 23 times, and now lives there as a permanent resident. The visa process, though, is far from easy. “I’ve got a Green Card, but the other guys in the band have to go home and renew their visas every year,” he tells us. “Surely by this point [the US government] would sit down and reassess the situation and go, ‘Okay, they’ve been doing it for this long, they pay this much in taxes’ and make it easier to renew the visa. But no, it’s the same ballache of a mission every year. They have to fly back to the embassy and get interviewed, and they need all this proof of what we’re doing. Surely you can trust us and throw us a bone! It’s really frustrating, it’s got stricter.”

One thing Ben doesn’t buy, though, is the argument that bands have an easy ride coming to the UK. “If anything we’re more strict,” he says. “Our very first shows with (new vocalist) Denis [Stoff] last year were meant to be in Manchester and London, but we had to cancel because he couldn’t get a visa (Denis’ home country Ukraine isn’t an EU member, hence his need for a visa). Then when we did sort it, our tour started in Europe, so we flew into the UK to get on our tour bus. But Denis’ UK work visa didn’t start until after the European dates and they nearly deported him!”

Denis may have narrowly escaped deportation, but Michael McGough of melodic hardcore crew Being As An Ocean wasn’t so lucky. “I was scheduled to fly before my visa arrived, but I was assured by the agent that so long as I have proof of it being processed I’d be fine. But I got all the way to JFK and was deported home,” he says.

Matt Jones of Lincoln deathcorers Martyr Defiled also fell victim to a delayed visa, and says the band was forced to crowdfund to change their flights after the visas didn’t turn up. “We missed the first five shows of the tour, but we made it,” he says. “This whole ordeal cost us so much that we couldn’t afford to go to America again, which sucks ‘cause we loved our time in the States and meeting some of our oldest fans.”

Michael and Matt will no doubt be pleased that John is making some headway with his campaign. “The campaign started with some great work done by Kerry McCarthy MP [Labour MP for Bristol East],” John says. “We have meetings at the American Embassy, and we met with Nigel Adams MP [Conservative MP for Selby and Ainsty] a month ago in Parliament. He’s very sympathetic.”

The Musician’s Union is also keen for the government to help the musicians who are drowning in red tape, and has set up a lobbying group. “We set up the Music Industry Visa Task Force as a way for music industry organisations to pool their resources and lobby governments in the US and the UK more effectively,” says Dave Webster, National Organiser for Live Performance. “On the Task Force is a representative of the Department of Culture Media and Sport (DCMS). We’ve also written to the US Ambassador and the Minister of State at the DCMS, Ed Vaizey, seeking a meeting to discuss the issues and find workable solutions.” Dave tells us that a 2015 UK Music report found British music to be worth £4.1billion to the economy, and £2.1billion in terms of exports. “If US audiences don’t see UK bands early in their careers then where is the long-term growth, both culturally and economically?” he asks.

Not everyone, though, is on board with the fight. Artist manager Andy Inglis has already come under fire for writing a post on The Quietus debunking John’s claims that the system is designed, much like Donald Trump’s fabled wall, to keep British bands out. He says that the figures of £5000 and above are inaccurately being ‘thrown around as the norm’, and puts the actual figure of a year-long visa for an individual at closer to £282.

“I think some people are complaining ignorantly,” he tells Hammer, “I wish they’d hold fire until they had a full grasp of the basics.” The criteria that bands have to satisfy to get a visa are not, he says, any different to the conditions anybody would have to meet if they wanted to work abroad. “Many countries have legislation in place to protect their citizens from ‘their’ jobs taken by others from outside, by setting a bar for migrant workers to reach,” he explains. “The US isn’t anomalous; whether it’s fair or not is subjective. ‘Why isn’t that rule reciprocated?’ is a valid question, but it’s not a valid reason for a country to change their rules, otherwise we’d all be re-writing our laws and customs to match everyone else’s.”

On paper, the conditions that US and UK artists must meet to tour in each other’s countries aren’t that different – and applying for a UK visa costs considerably more than £30. A standard six-month visit visa to the UK costs £87 to apply for, and states somewhat confusingly that performances are allowed, but any form of paid or unpaid work is not. A Tier 5 points-based visa, which is suggested on the government’s website as a type of visa performers can apply for, costs £230, and requires a sponsor in the same way that US visas do. For solo artists, there’s the Tier 1 visa in the UK and the O visa in the US. Both are for ‘exceptionally talented individuals’, and require a hefty, if arbitrary, body of proof that the individual is, indeed, exceptional.

“I know there’s a lot of talk, especially in the UK, of a conspiracy [to stop artists entering the US],” says Matthew Covey, a US performing arts lawyer. He’s also a board member of non-profit organisation Tamizdat, which acts as an agent for artists and offers a helpline to musicians struggling with the application process. “I don’t think it’s a conspiracy as much as it’s bureaucracy. I think there’s been a real change in the last ten years in how visa petitions are being reviewed. They used to be reviewed in a holistic way, but the shift over the last ten years has been to enforce very specific rules [about meeting the criteria]. It’s more predictable, but it’s less flexible. Lobbyists in the arts community were complaining the holistic approach was unpredictable, and that backfired to a certain extent because the way the US responded was, ‘Okay, you want it to be more predictable? Then we’re going to follow the rules really carefully’.”

There are a few ways around the bureaucracy. For example, working visas aren’t required to play SXSW or CMJ Festival – this can be done on a standard tourist visa. That might not eliminate travel and accommodation costs, but you’ll save a few grand by not hiring a lawyer. “The delays that people experience can be solved by paying money, which isn’t fair,” says Matthew. “Hiring attorneys or agencies to help with the process [is expensive], but the process has become too complex to do without their help.”

Matthew’s only advice to anyone who feels let down by the process is to keep fighting. “There’s a lot of anger and frustration and I think that’s great, because the process is needlessly complex and expensive and the effect it’s having on culture in the US is pointless,” says Matthew. Even Andy, who’s been vocal in his opinion that the situation might not be as bad are some are making out, says he “wouldn’t argue about paying less for stuff”. Touring the US does seem to be in danger of becoming the preserve of bands with deep pockets (and that’s an oxymoron if ever we heard one) but solutions are actively being sought. Breaking America might be subject to more paperwork, but the desire to do it is as strong as it’s ever been.