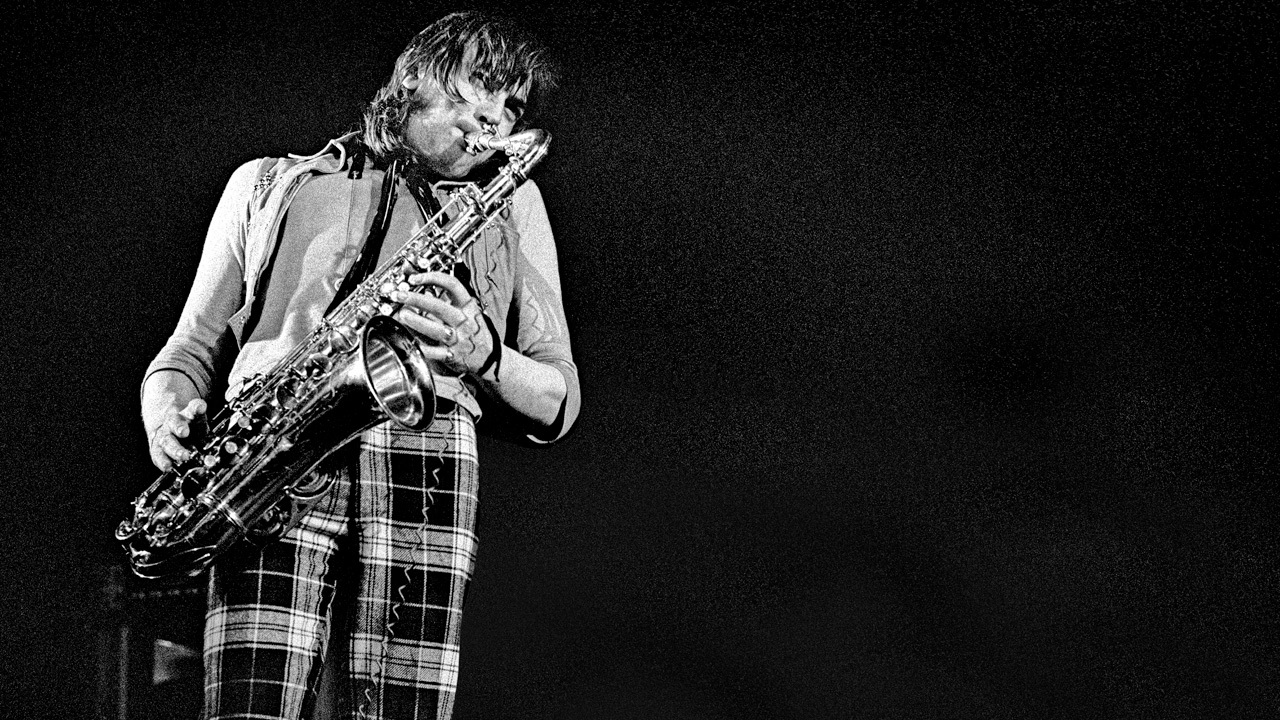

On April 24, 1983, Chris Wood cut what would be his final piece of music. Recorded in Birmingham, his first stomping ground and now his last harbour, what was put on to tape that day carried an air of fragile, wounded beauty. Wood’s tenor sax playing on the otherwise bubbling three-minute track doesn’t have the liquid smoothness of his greatest years, when playing seemed effortless to him, but instead sounds like it was dredged from the very depths of his soul. It was as if, right there and then, he somehow found the strength to summon all the hurt, pain and wrongness of the world and blow it out.

The piece was meant to soundtrack, of all things, BBC TV’s coverage of live basketball, although Wood never did hear it aired. Within weeks of the session he was dead, aged just 39, his ravaged body and a broken heart having given up on him. The musical legacy Wood left behind stretches across three decades, through numerous collectives, and is imprinted upon a handful of dazzling albums. A classic foil and sideman, Wood’s gift was to add colour to the landscapes of other people’s recordings, and in so doing give them dimension and defining features. Among those he played with were his friend Jimi Hendrix, Free, John Martyn, Nick Drake, Ginger Baker and Dr John. Yet it was as a multi-instrumentalist with Traffic that Wood soared highest, unshackled to ride the flow of that band’s often wondrous music.

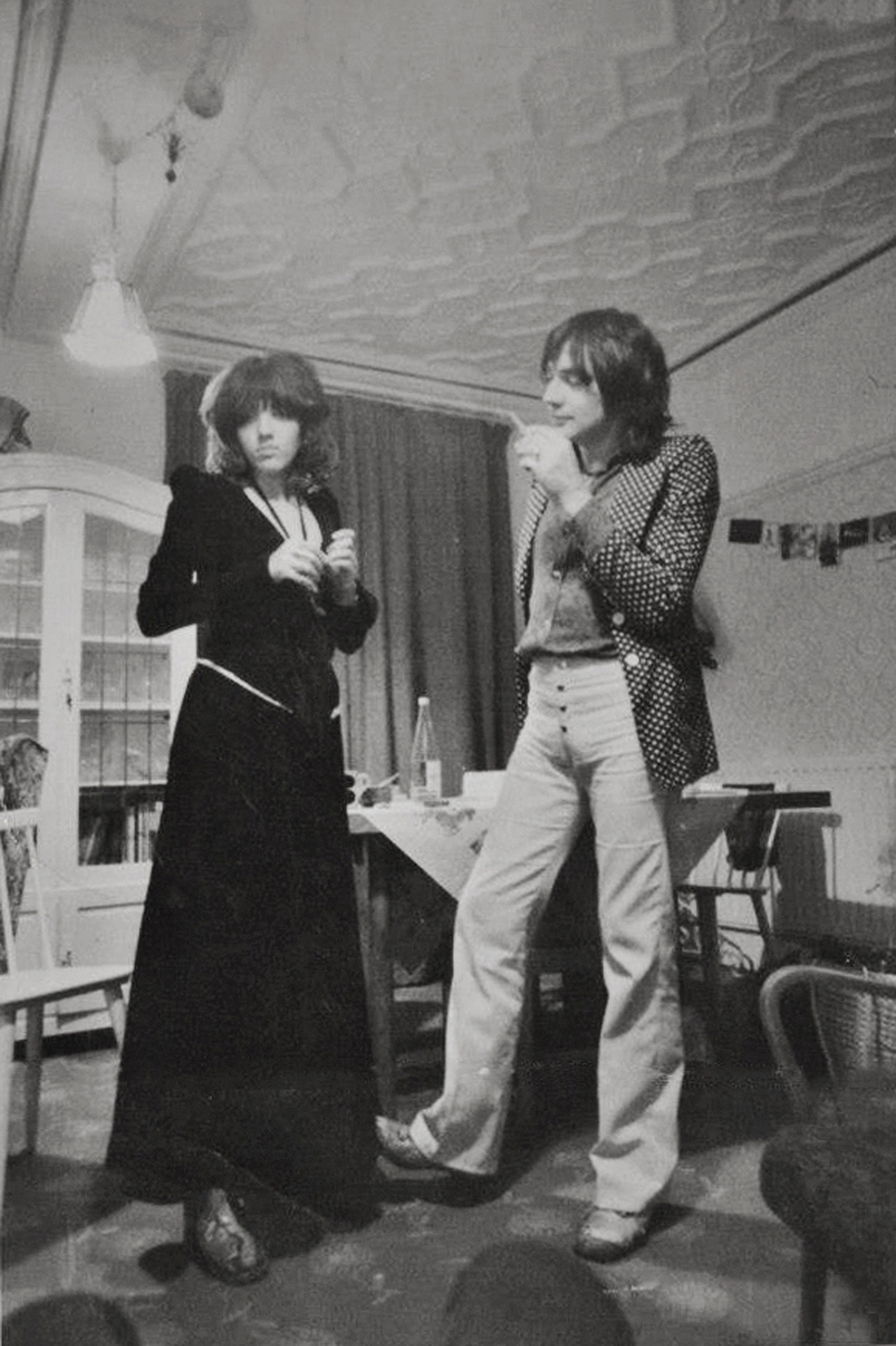

Wood, who excelled on sax and flute and was proficient on piano, bass and guitar, was a founding member of Traffic in 1967, along with Steve Winwood, drummer Jim Capaldi and guitarist Dave Mason. In their relatively short, turbulent time together, Traffic roamed far and wide, their music encompassing pop whimsy, psychedelia, bucolic folk and a refined melange of rock, jazz and R&B. Each band member was a virtuoso in his own right, but Winwood was the shining star, with Wood like a lighting conductor for his restless energy.

“Chris was never a leader, definitely a support person, but a bit of a wizard,” says Terry Barham, who briefly engineered sessions for Wood in the late 70s. “He was an interesting, very clever saxophonist, but in another league altogether on flute. He was definitely experimental. It wasn’t as if he played just rock, blues or jazz – he foraged a different line. To me he was a kind of musical alchemist and could bring something out of another musician just by being in the same room as them.”

When Winwood split Traffic in 1974, Wood lost his moorings for good. Whereas his old friend appeared at ease in the spotlight, born to it, Wood’s personality made him better suited to the shadows. And it was to the shadows that he retreated. By the time of his death, he cut an isolated, near-forgotten figure, just a footnote in the story of British rock’s golden era. Now, though, a new four-disc box set, Evening Blue, has reclaimed Wood from the dark, restoring him through a rigorous, sprawling collection of his best sessions.

“I didn’t used to understand people’s desire to make good for the dead,” admits Steph Wood, Chris’s younger sister and protector of his estate. “I thought they should rest in peace. But I can’t tell you how wonderful this set is for me. Chris felt underappreciated his whole life, and now it’s been put right.”

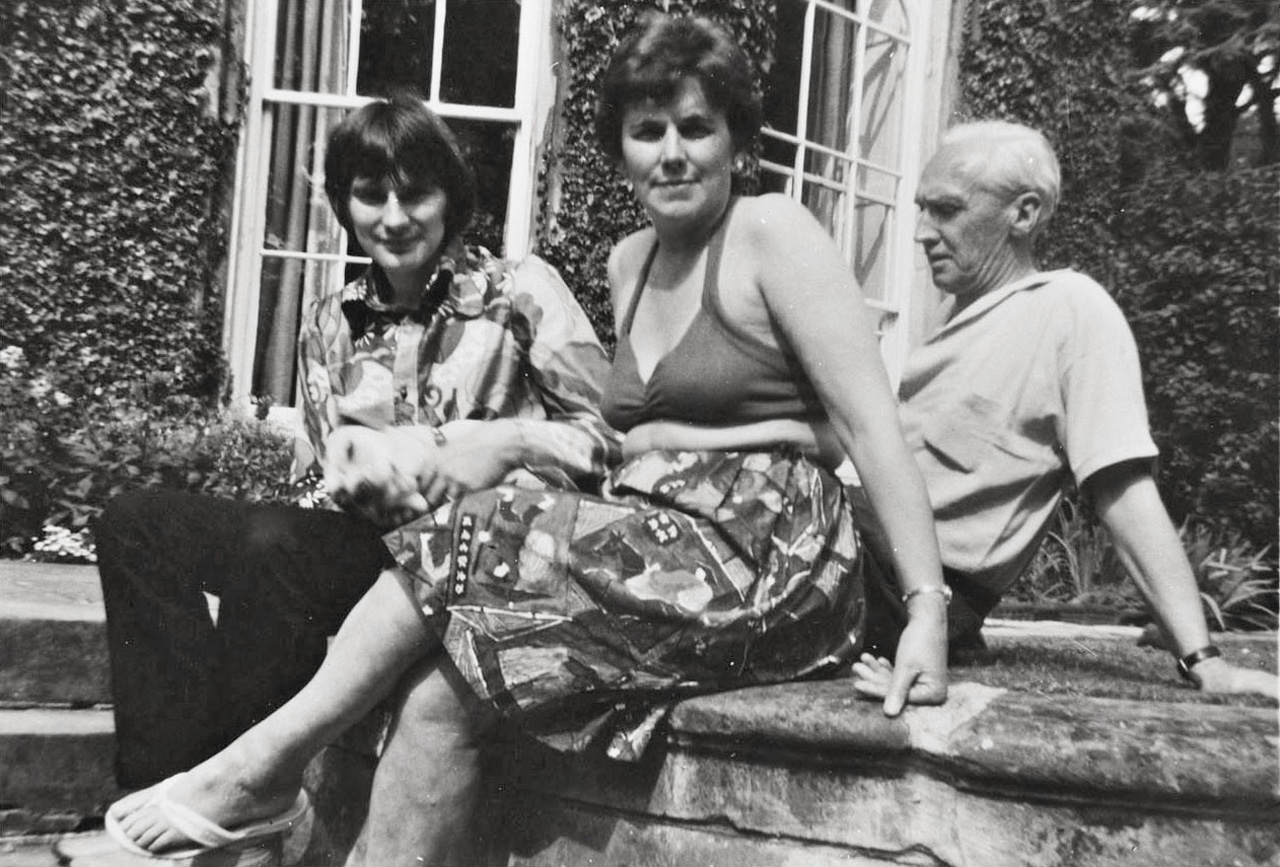

Chris Wood was a war baby, born in the suburbs of Birmingham in 1944 to parents Stephen, a civil engineer, and Muriel Wood. Sister Stephanie arrived three years later. And from the ages of nine and six respectively, they grew up in gothic splendour at Corngreaves Hall, a stately Georgian pile located in the heart of the Black Country, where their father was billeted as chief engineer of the borough. Music soon filled the old house. Their father’s record collection encompassed Bing Crosby, big bands and Beethoven, and their mother had a piano under the stairs.

Muriel Wood signed up her son for piano and flute lessons, but he didn’t stick at them. He was too of his own mind, and subsequently taught himself to play both instruments. As a teenager he developed an obsessive passion for jazz, and picked up records by Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Ray Charles at a Birmingham city-centre record shop, The Diskery, which was then also frequented by Winwood, Robert Plant and future ELO leader Jeff Lynne.

“No one in our family could actually play, so it must have been born in Chris,” says Steph Wood. “He was never able to read music, but created it with his ear. Ours was a very loving upbringing, and Corngreaves Hall also gave us everything we needed to imagine our own little world. It was a magical place, like Narnia, surrounded by enchanted woodland but with steelworks and all this industry just down the road.”

Wood’s other outlet was painting, and after leaving high school he attended the nearby Stourbridge College Of Art. In this more bohemian environment he fell in with a fellow music nut, Steve Hadley, a pianist. Together they formed a jazz quartet with two more local musicians. Deciding their sound required tenor sax, Wood bought one and taught himself to play it. By the spring of 1962 they had secured a weekly booking at the Saracen’s Head pub in Dudley. By then, enterprising British promoters had begun to bring America’s great black artists to Britain to play, and Wood made pilgrimages to Birmingham Town Hall to see the likes of Muddy Waters, Ella Fitzgerald and his beloved Ray Charles, expanding his horizons.

As a result, the regional jazz circuit quickly seemed to Wood to be stifling and restrictive, and so he moved on, at first blowing for local bluesman Perry Foster, whose band the gauche young Robert Plant also passed through. Next there was Sound Of Blue, an R&B combo with Wood alongside future Chicken Shack pair guitarist Stan Webb and keyboard player Christine Perfect, who later married Fleetwood Mac bassist John McVie and joined that band.

Sound Of Blue were accomplished enough, but at the same time, another R&B-fuelled group hit the local clubs, this one fronted by a pale, skinny, teenage white boy with a voice like a seasoned black soul man.

Young Stevie Winwood and the Spencer Davis Group were instant sensations in Birmingham and around its satellite towns, and in 1965 broke out nationally with their No.1 Keep On Running. Wood was a regular face at their gigs, and he and Winwood were drawn to each other and became friends. Winwood began to visit Corngreaves Hall to jam with Wood, fired by Wood’s instinctive musicianship to imagine a group that would be boundless.

This coalesced at a dark, dingy Birmingham club, the Elbow Room, where musicians from around the area would gather together to play after hours. The studious Dave Mason and extrovert Jim Capaldi were also regulars at the Elbow Room. Both had been in a band called Deep Feeling, from which Mason had not long been ousted, and now they too were sucked into Winwood’s orbit.

“Steve at that point was obviously well beyond where the rest of us had reached, and Chris was always with him,” recalls Gordon Jackson, Deep Feeling’s singer/guitarist, who would become Traffic’s roadie. “Chris was a very attractive character. There was no hidden agenda with him and you could talk to him about anything, whereas that just wasn’t possible with Steve at the time. You were in such awe of Steve that you could not consider him an equal.”

By 1967, Winwood’s mind was made up. Early that year he travelled up to the north‑east to play his final shows with the Spencer Davis Group, with Wood, Capaldi and Mason along for the ride. In a Newcastle hotel room, the four of them worked up a lysergic pop song, Paper Sun, and with it the blueprint for Traffic. Winwood’s presence was enough to get the new band a deal with the Spencer Davis Group’s label, Island Records. And in May, as Britain’s hazy Summer Of Love opened up, Paper Sun rocketed to No.4 in the UK singles chart.

A month earlier, Traffic had all moved into a tumbledown dwelling in rural Berkshire, procured for them by Island’s owner, Chris Blackwell, and there they crafted their debut album, Mr Fantasy.

The Cottage, as it was known ever after, was in fact made up of two conjoined buildings. Wood’s and Winwood’s rooms were at opposite ends, and the meeting point was a large central living room in which the band set up their gear in front of an open fireplace. Wood’s influence on the music Traffic conjured there over the next three years was profound and lasting. In the first instance, its sense of other‑worldliness was rooted in the long walks that he would lead the others on through the surrounding countryside, bird-spotting and navigating ancient ley lines from old books he kept in his travel bag. The album’s mind-bending title track sprang up following a visit from two art school friends of his, who slipped the eager band tabs of LSD. On Traffic’s songs, Wood’s flute was dance partner to Winwood’s mellifluous vocals, skipping around and between melody lines like quicksilver.

“Although he didn’t write many complete songs, Chris’s contribution was massive,” says Jackson, a frequent lodger at The Cottage. “His thing was to create the mood where songs could be written, and he was the starting point for so much of their best work. He was so expressive with his sax in particular. He could make it groan or climb like an eagle and could pull things out of nowhere.”

Traffic had an immediate impact on the era. At their first UK show, at London’s Savoy Theatre, Jimi Hendrix, Paul McCartney, Brian Jones and Cat Stevens were among a rapt audience. Wood formed a close bond with Hendrix, and appeared to have felt a kinship with brilliant but damaged souls. He went on to also befriend Paul Kossoff, Free’s mercurial but similarly doomed guitarist, after playing on the band’s self-titled second album of 1969.

Later in ’67, Wood visited Hendrix in the studio as the guitarist made his grand opus, Electric Ladyland, and added a suitably mystical flute part to the track 1983… (A Merman I Should Turn To Be). He also became besotted with one of the harem of young girls who flitted around Hendrix like moths to a flame. Jeanette Jacobs was then 17, a pretty brunette with dark eyes like fathomless pools. She had come to London from her native New York where she had fronted an all-girl trio, The Cake, who had once toured with Buffalo Springfield.

Wheels turned at a rapid pace in the Swinging Sixties. Traffic went off and toured America. Mason quit and then rejoined for the making of their second, self-titled album. Traffic of ’68 were split down the middle – on one side the prodigal guitarist’s folksy confections, on the other Winwood’s wilder, more elemental jams – with Wood’s sax and flute as the glue bonding them together.

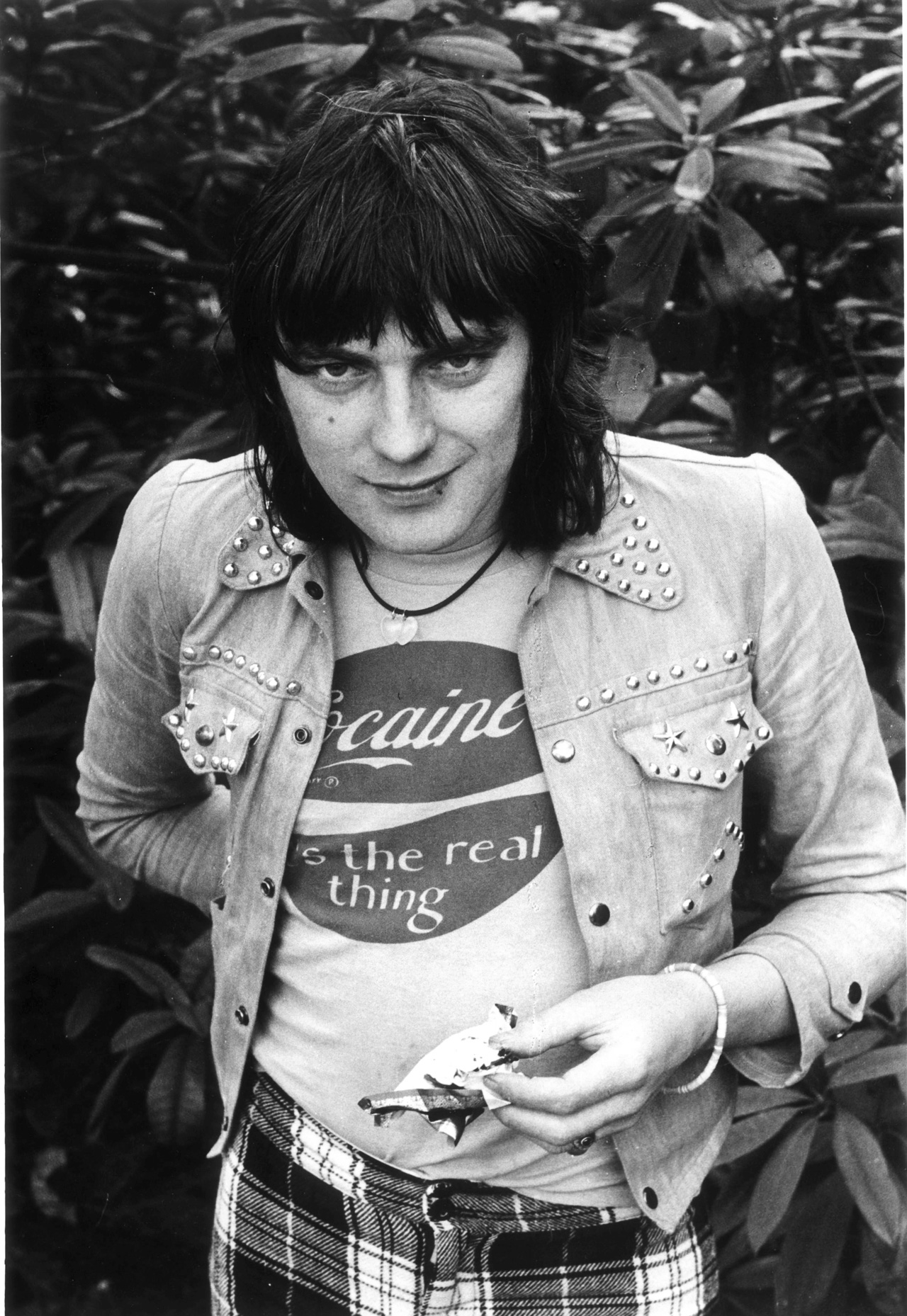

While preparing the songs at The Cottage they were visited by Pete Townshend and Keith Moon, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker, kings in their court. Yet as Traffic shot like a comet, Wood struggled to hold on. Struck down by both a debilitating stage fright and fear of flying, he began to anaesthetise himself with booze and harder, harsher brews.

“Chris was a bit of a fish out of water,” says his sister Steph. “Jim was the showman and Steve was Mister Cool, but there was a sad side to Chris and fame. If he hadn’t had it hit him I think he would have been happier tooting his flute in our local clubs and bars, rather than being escalated too quickly. It would be fair to say he was tortured.”

Yet as Traffic was climbing the US album chart, Winwood left to join Clapton and Baker in Blind Faith, marooning the others and establishing a pattern for the years ahead. The jilted remaining trio hooked up with Island labelmate Mick Weaver, aka Wynder K Frog, a Hammond organ player and their Winwood substitute. As Mason, Capaldi, Wood & Frog, they rehearsed for an album, but ultimately their group name was longer than the time they were together.

At a loose end, the besotted Wood followed Jeanette Jacobs back across the Atlantic to New York, and there the two of them fell in with a transplanted New Orleans pianist and showman, Malcolm John Rebennack, who was just then developing his voodoo medicine man alter ego Dr John.

The pair joined Rebennack’s band, and the haphazard collective set off in two vans on a weeks-long odyssey across the US, plying their howling swamp blues at one-night stands in dive bars and dead-end towns. Altogether it was not an environment best suited to someone as sensitive and impressionable as Wood, since Rebennack, along with several of his musicians, was then nursing a ruinous heroin habit.

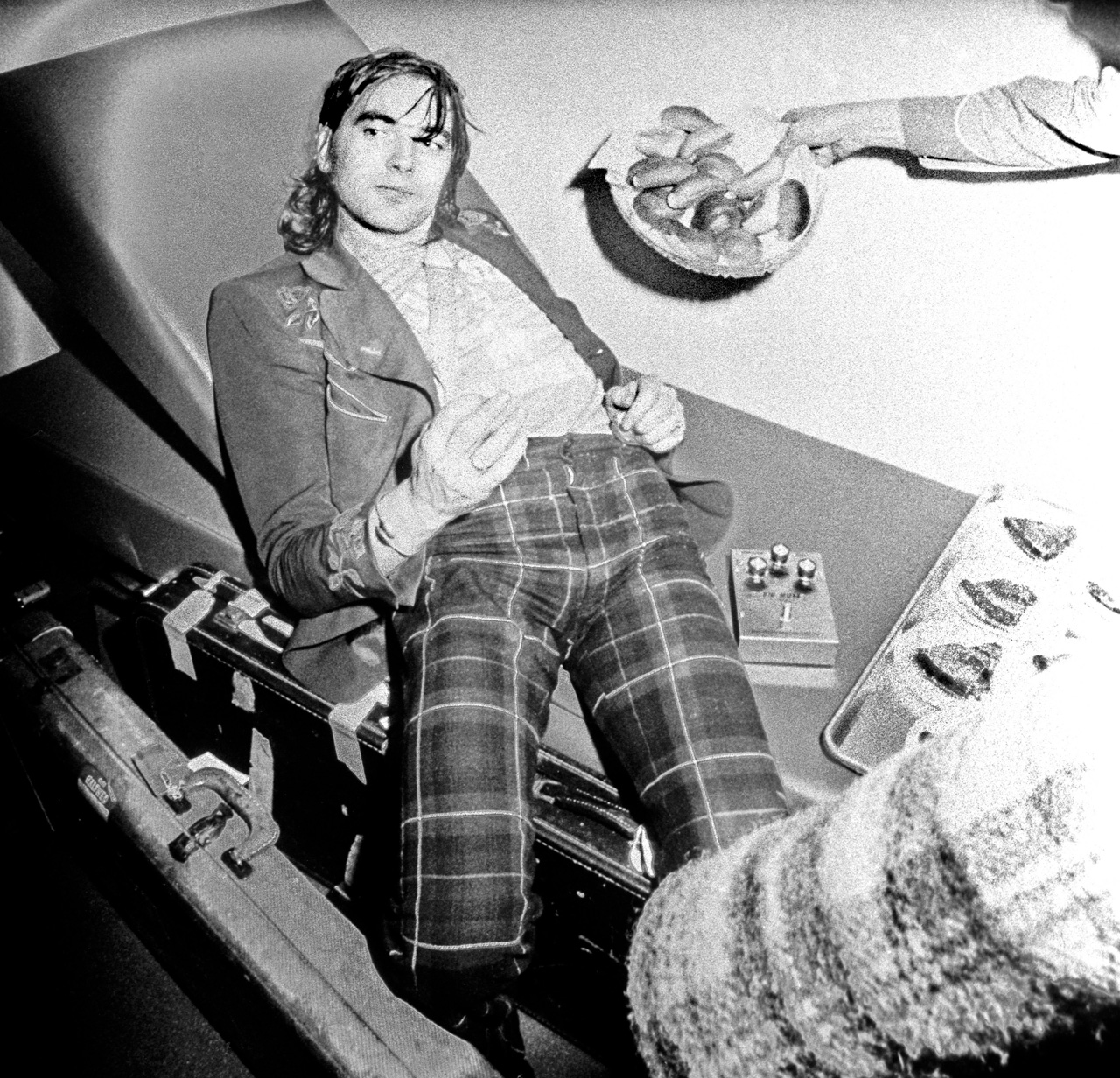

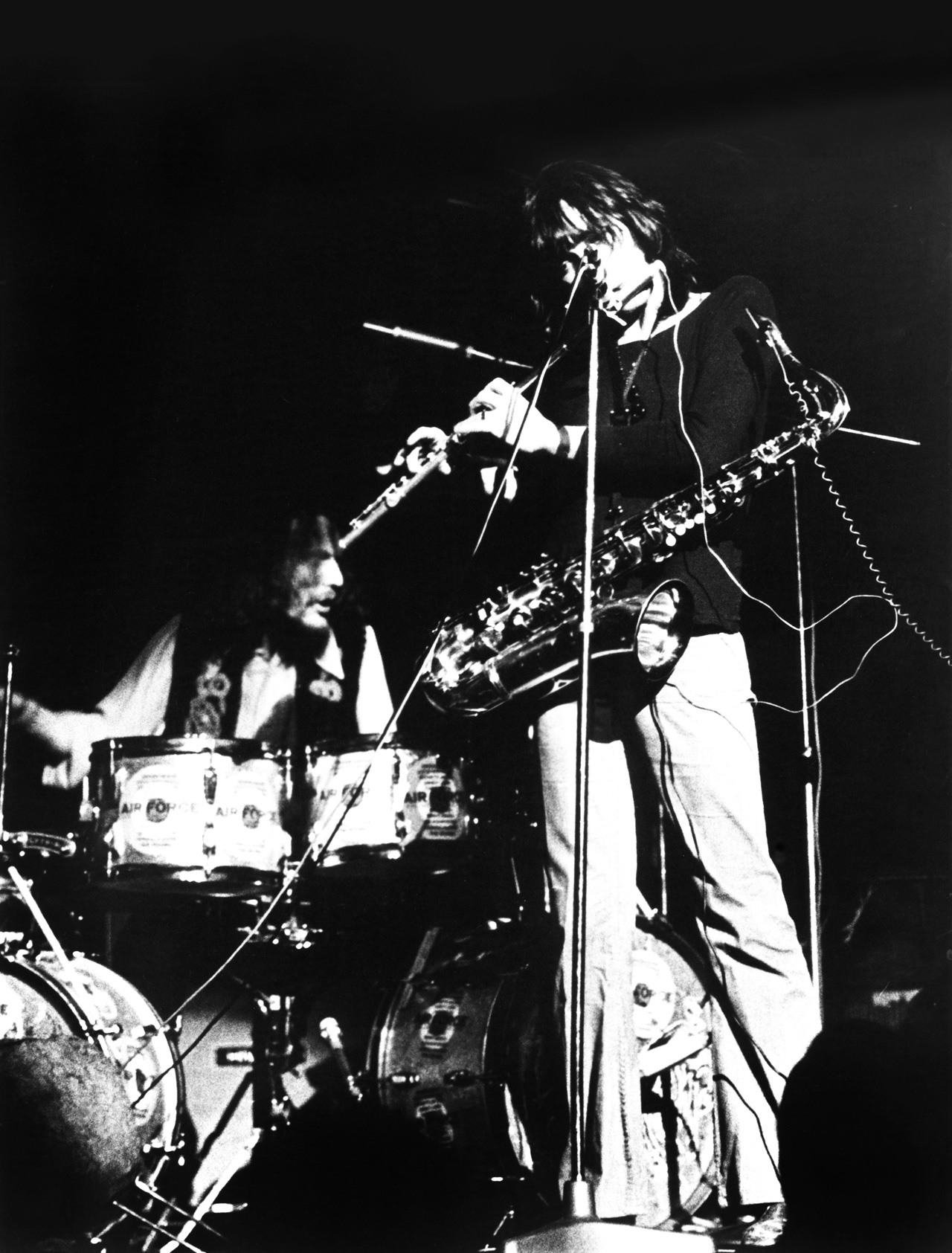

Exhausted by the endeavour, Wood flew home to England and took Jacobs with him. Back in London, both joined drummer Ginger Baker’s chaotic new 10-piece extravaganza Air Force. And with the short-lived Blind Faith now over, so did Winwood.

Wood managed two careering gigs with Air Force, at London’s Royal Albert Hall and Birmingham Town Hall, but when he turned up drunk to a rehearsal, Baker hit him about the head with a drumstick, drawing blood. Wood walked out, and back into the bosom of Traffic. Winwood had again taken up residence at The Cottage, intending to record a solo record, but when Wood brought him an old English folk song he’d discovered called John Barleycorn, he changed tack and summoned Capaldi – but not, this time, the errant Mason.

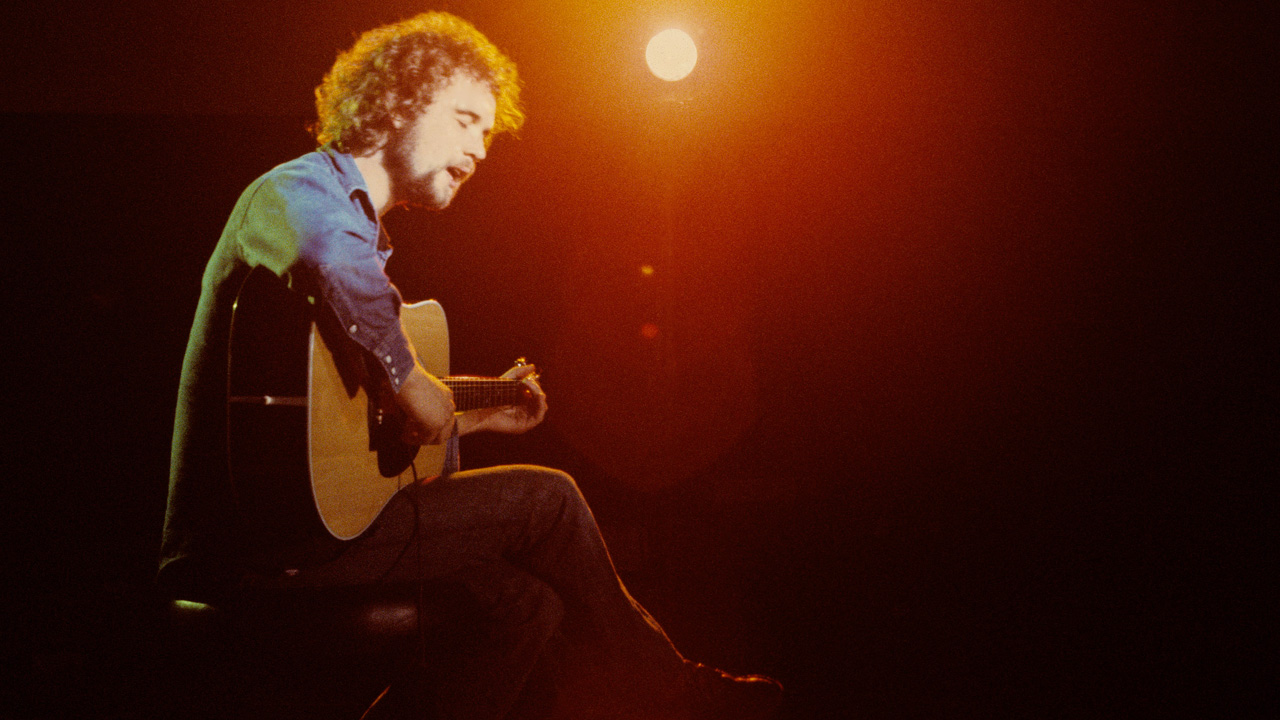

This was the dawning of Traffic’s imperious phase. At just six tracks, their 1970 album John Barleycorn Must Die was a dense, ambitious work, bringing together baroque folk and excursions into jazz-rock. It reached No.5 in the US chart. The slicker The Low Spark Of High Heeled Boys followed in 1971. Introduced by Wood’s mood-setting saxophone, it was a record of polished surfaces and undulating undercurrents.

Then Wood played with the dash and flair of a World War I flying ace, and the grace of a master painter. Yet at the same time he was coming apart at the seams. Hendrix’s death in 1970 hit him hard. He and Jacobs married in 1972, but she was a roaming spirit and their open marriage further destabilised him. The couple’s West London flat, littered with the detritus of too many long, black nights and lost days, came to symbolise the mess of their relationship, and also Wood’s state of mind.

“Jeanette was a lovely girl, but she suffered from her own fears,” says Steph Wood. “And Chris needed someone who was really strong and would hold him up. He adored her, but she also broke his heart. He was taken advantage of by his so-called mates as well. There wasn’t much in that flat that didn’t get nicked. It was Chris’s responsibility, really. If you lay yourself bare in the way that he did, you’re going to end up with the seedier side of people.”

By the time of Traffic’s 1974’s pastoral album Where The Eagle Flies, Wood’s demons had got the better of him. On stage that September at a gig at New York’s Academy Of Music, he was visibly drunk and incapable of playing his parts. Winwood’s decision at the end of the tour to disband Traffic for good sent Wood reeling into a black pit of despair from which he would never manage to escape.

Ever after, it was as though psychic blows rained down on Wood. Paul Kossoff died in 1976, wrecked at just 25. The following year, Jacobs left Wood. Between times, Wood tried to revive his music career. He got something going with The Wailers’ pianist Tyrone Downie, but that didn’t stick. In June and July of 1977, he recorded some tracks with Terry Barham at Island’s Fall Out Shelter studios in Hammersmith, backed on some by guitarist Pete Bonas, just out of jazz-fusion band Brand X, and on others by a Latin American-tinged group led by young Venezuelan bassist Jorge Spiteri. But this was the summer of punk, and the weeping melancholy of Wood’s new music was out of time and fell on deaf ears.

“Recording him, what struck me was how amazing he was as a musician,” recalls Barham. “I mean, just astonishing. But I also knew that what we were doing wasn’t a big commercial prospect from anyone’s point of view. And Island certainly weren’t interested. Really, I thought of it more as therapy for Chris. Just prior to me working with him, he would hang out in the studio reception, a little bit of a lost soul. He was obviously a casualty of things and quite lonely.”

Near broke, in 1979 Wood fled London for the relative peace of the Midlands and moved back in with his parents. He began going to church, and invested what little money he had left in a recording studio start-up in Birmingham, called Sinewave. It was there that he encountered Vinden Wylde, who was employed as a plumber on the building and was also a part-time saxophonist playing in local trad-dance bands.

“Chris offered to teach me some stuff and invited me round to his parents’ house,” Wylde remembers. “And over a period of weeks, he showed me a better way to play – the ‘false fingerings’ that all really good sax players know. It was a jazz musician’s stuff and absolutely wonderful.

“It got to the point where he wanted to do a bit of studio work, so I drove him down to Sinewave one afternoon. We played together for three, four hours, and when he got home that day he was leaping about, so excited.”

This revival of Wood’s spirit was merely temporary, however. On New Year’s Eve 1981, Jacobs, who for years had suffered with epilepsy, had a last, this time fatal, seizure. Wood paid for her funeral and headstone and played flute at the service. And then he tried to drink away his grief.

“He never stopped loving Jeanette, ever, and when she died, that was his tipping point,” Steph Wood explains. “There had always been the sense that Chris needed saving, but there is absolutely nothing you can do with a broken soul. He sank into an abyss that he just wasn’t able to dig his way out from.”

Chris Wood had just one more hurrah left in him. On a bright spring day the following year, he recorded that inauspicious session for BBC TV. Wylde remembers having to steady him at the mic that day, but even so, he played his heart out, again flying high and free. That summer he was taken into hospital in Kidderminster, suffering from pneumonia. As his condition worsened, he was transferred to the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham. It was there that he died, on July 12, 1983, aged 39.

“The last time I saw Chris was the evening of the night before he died,” Steph Wood recalls. “It was a shock to all of us that he went so quickly. I remember talking to a nurse, who asked me what we would do when he came home. But Chris knew. He told me that night how he wished he could go once again to Cornwall where we had so often holidayed with mum and dad.

“It sounds strange, but the thing I remember most about him is the bag he used always to carry around. It was full of cassettes, wires, leads, his supplements, and chaotic in the most divine way. That was Chris, really. He was flamboyant, but in such a quiet, gentle fashion.”

The Chris Wood box set Evening Blue is out now via Hidden Masters (hiddenmasters.net).

Wood Work

A 12-track Chris Wood sampler

Traffic - No Time To Live (Get it on: Traffic, Island, 1968)

On this penultimate track on Traffic’s vaulting second album, Wood’s sax spirals up above a hushed piano part to trade lines with Steve Winwood’s keening vocal, a mesmeric, howling moan in otherwise empty spaces.

Jimi Hendrix Experience - 1983… (A Merman I Should Turn To Be) (Get it on: Electric Ladyland, Reprise, 1968)

Wood’s flute first emerges through the fog of this mystical, spooked blues at 8:30, sounding like an alien siren, and then again at 9:40, blowing through like a cool wind across the tumult.

Nick Drake - Three Hours (Get it on: Evening Blue, Hidden Masters box set, 2017)

An alternative take of a track recorded for Drake’s Five Leaves Left album. Wood’s flute gives Drake’s aching but magisterial song the softest, most tender of kisses.

Gordon Jackson - Snakes & Ladders (Get it on: Thinking Back, Marmalade, 1969)

Initially, Wood nestles his sax into the martial beat of this track from Jackson’s only solo album, and then, on 2:15, shoots for the stars. “How wonderful that was, too,” Jackson remembers. “You would just let him go and play what came into his head and it was always what you wanted.”

Free - Mourning Sad Morning (Get it on: Free, Island, 1969)

Wood haunts this ancient-sounding lament, his flute running tears down Paul Kossoff’s dexterous acoustic guitar filigrees.

Traffic - John Barleycorn (Must Die) (Get it on: John Barleycorn Must Die, Island, 1970)

Wood’s lyrical flute passages elevate this trad-folk arrangement to a higher plane, alternately glistening like morning dew and skipping like sprites.

John Martyn - Outside In (Get it on: Inside Out, Island, 1973)

Martyn rustles up a whirling folk-rock dervish; Wood arrives at 3:49 to soothe the clamour, his sax a celestial, twilit moan.

Traffic - The Low Spark Of High Heeled Boys (Get it on: The Low Spark Of High Heeled Boys, Island, 1971)

Another epic track, with Wood’s tenor sax establishing and then carrying off its mood of louche grandeur.

Jim Capaldi - Seagull (Get it on: Short Cut Draw Blood, Island, 1975)

This track was played at Wood’s funeral. On this elegant farewell, his flute parts the gathering clouds with shafts of sunlight.

Chris Wood - Barbed Wire (Get it on: Evening Blue, Hidden Masters box set, 2017)

Recorded with Terry Barham at Island’s Fall Out Shelter studio in 1977 for Wood’s lost solo album, his sax here is as inviting as warm butter spreading through the track’s languorous sweep.

Chris Wood - Lay It Up (Get it on: Evening Blue, Hidden Mastersbox set, 2017)

The last track Wood cut for a BBC TV session, the backing is all chintz percussion, but his lead sax lines are golden and suffused with soul.

Maps & Chris Wood - What To Look For With… (Get it on: Evening Blue, Hidden Masters box set, 2017)

Northampton-based Maps, née James Chapman, take eight-track recordings of Wood’s from 1977 and 1978 and blend them into a regal electro landscape from which his flute takes flight. “I found it an honour,” Chapman says. “I was blown away with the stuff of Chris’s that I heard. It was like being given magic to work with.”