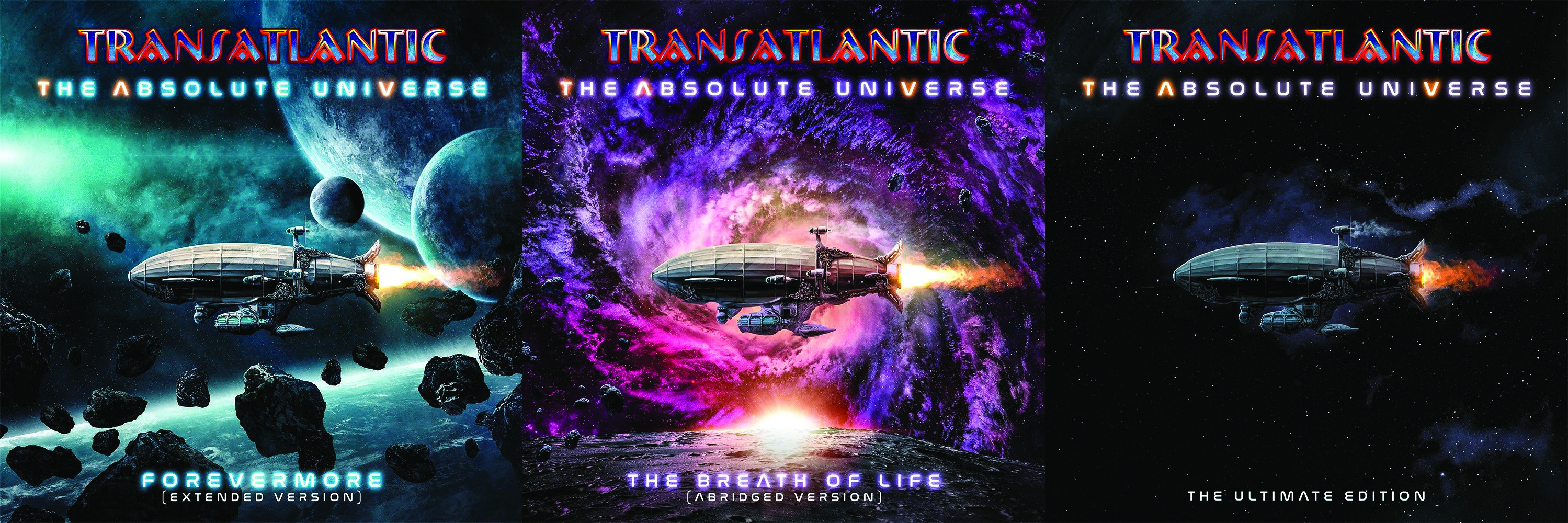

"I think it’s a prog fan’s wet dream,” says drummer Mike Portnoy. Seven years after their last album, Kaleidoscope, the prog powerhouse that is Transatlantic have reassembled for their most ambitious release yet. The newest work from Portnoy, Marillion’s Pete Trewavas, Neal Morse and Roine Stolt, The Absolute Universe nearly proved impossible for its creators to control. It defied their attempts to limit its scope and two distinct versions emerged from the crucible of their musical alchemy: a double disc subtitled Forevermore and a single disc, The Breath Of Life.

It all began in Fenix Recording Studios, Sweden, in September 2019 when the band reconvened to work on new material. “After the Kaleidoscope tour we felt we needed some time away from each other. I won’t go into details, I’m not even sure there are any,” says Trewavas, laughing. “We decided we’d write a long piece of music, which I was in favour of because it gives a lot of scope for the writing, it allows you to bring themes back and develop music. Undoubtedly, one of our strengths is arranging the music. Neal and I get a lot of fun out of revisiting a piece of music with either completely different chords or some twist so that’s it’s not quite the same, which trips us up live no end, but is a lot of fun at the time to scratch your head over.”

Transatlantic set up a whiteboard in the studio to list all the ideas everyone brought to the table and set about hashing out which ones they liked. The prolific Mr Stolt came to the session with an hour and a half of music already composed. “I understand we can’t use everything, but if I write one and a half hours of music there’s plenty to pick from,” he says. Morse and Trewavas brought in ideas of their own, and the quartet found their collective creativity undimmed by the six-year break.

“There’s no lack of ideas so it’s easy in the respect that there’s so much to work with,” says Portnoy, “but it’s always a difficult chemistry because of the personalities. The different personalities help make it really special, but sometimes getting to agree on things is a challenge. Neal and I have very American energies, and Roine is a lot more laidback with his Swedish energy, and Pete’s got a very distinctive English energy, so we all go at different paces.”

However, the biggest challenge this time was the sheer volume of music at their disposal, promising to rival 2009’s The Whirlwind for grandiosity. Portnoy and Stolt wanted to make a double album; Morse and Trewavas thought it needed a little trim off the top. “We had 10 days there and about seven days in I started to think it was getting a bit long,” says Trewavas. “Some members of the band were like, ‘This is great! How many minutes are we at now? This could be longer than The Whirlwind!’”

“I could see this was going to be great and there was a natural flow,” says Stolt. “I felt that we shouldn’t really cut the album, then Neal made a couple of suggestions how he wanted to cut the album and, to my ears, the way he cut it sounded more like a medley or like we were chopping up a sample of themes or ideas more than a song.”

“We ended up with a few stalemates,” confirms Trewavas. “We couldn’t agree on songtitles and we had different lyrics going on as well. At that point Mike said, ‘Would it be crazy to suggest we have two albums? That way we can all be satisfied, we can all have our dream album. There’s enough music here and we’ve got enough variety that if we’re smart about it, we can do this.’”

The result was Forevermore and The Breath Of Life, which Trewavas calls, “two experiences of the same journey, which is very cool.” The Breath Of Life is not just a slimmed-down version of Forevermore, it’s a different album built around the same musical themes.

“That freed up everybody,” says Portnoy. “Normally in the past if Neal wrote a whole set of lyrics to a song and Roine wrote a whole set, you’d have to battle it out. In this case, we can use one set for one version, and one for the other version. That’s the important thing with these albums, the single disc isn’t merely edited down from the double. They are two alternate realities of each other. There might be the same musical song that appears on both versions, but who’s singing it is going to be different, the lyrics might be different, or we may have additional musical passages, so really this was a way for us to have all these ideas and not have to compromise and utilise them all.”

“It’s more of everything. That’s always been the motto for Transatlantic,” says Stolt, who notes that there’s a level of expectation from the fans that the band will always deliver something on a grand scale. “If Transatlantic had done an album with 12 songs, I think some fans would be disappointed, not by the songs but by the fact that we didn’t do this big epic. If you listen to the album now, there are actually different songs, so if we label them as 22 songs, then some fans will say, ‘Oh, I don’t like this Transatlantic album as much as I like The Whirlwind.’”

This enthusiasm for long-form composition began with their second album, Bridge Across Forever, in 2001, and has been carried on through each successive opus. “We’ve always worked within that framework where there’s a big overture and melodies and themes are introduced or foreshadowed and then they come back and are reprised later,” says Portnoy. “It’s a great way of writing, especially for progressive music when you’re working on a landscape. It’s written looking at the bigger picture.”

However, while Forevermore and The Breath Of Life might be considered concept albums, they’re not trying to tell a story in the same manner as The Who’s Tommy or Queensrÿche’s Operation: Mindcrime. “They’re not concept albums in the traditional sense like that,” says Portnoy. “They’re a little bit more broad strokes, it’s more like The Dark Side Of The Moon where it’s thematic concepts. It’s not literally a story with a character, it’s more themes, ideas and concepts that interconnect. This album is almost the spiritual sequel to The Whirlwind in that respect, talking about different challenges that the world is going through.”

Stolt wrote his lyrics in the summer of 2019, looking at the state of the world – the US in particular – and feeling a little disheartened. “We can’t get away from the fact that whatever happens in America happens to the world, and let’s put it this way, the leadership has been sketchy at best,” he says. “I don’t want to offend people, but that’s what it is. It’s scary, watching day by day, how long will this insanity go on? And people just accept it. I haven’t seen a revolution yet. Every morning I wake up, people are just silent and let this madman carry on with all the insults, insulting world leaders, insulting the American people.”

It’s easy to see these notions finding expression in the track Bully on Forevermore, although the subject of Stolt’s ire is never mentioned by name. He’s keenly aware of the dangers of alienating people and being seen as preachy. “I know it may not always be the most wanted thing to hear when you put on a progressive rock record, to have a sermon,” he says. “I see people like Roger Waters taking stick for writing his leftist lyrics, but I cannot do anything else than be honest. Sometimes I write a love ballad, but it doesn’t happen that often, or something about family, I think I’ve even written a song about food. It’s whatever comes naturally. I trust the intuition, rather than thinking what do the fans want to hear? Because if you start listening to the fans too much, then they say, ‘Don’t write about politics. I don’t want religion in the lyrics, I don’t want that.’ And the next step is, ‘I don’t like your guitar sound like that’, or ‘I don’t like that synth sound.’ Suddenly you’re making albums just to please the fans and you lose yourself.”

As much as The Absolute Universe is all about long-form compositions, revisiting themes, and developing ideas, both albums feature strong melodies. Rainbow Sky reveals the influence of The Beatles and the vocal harmonies bring to mind 60s pop and the Beach Boys. “At the end of the day, we have to appeal to the nature of the commercial world to some extent,” says Trewavas. “Melody is very important to all of us. I don’t know why that is. Even the themes are very strong. The songs are quite hooky.”

Originally, the plan was to finish the album by the end of 2019, but without the pressure to cram in making it between everyone’s touring commitments, the creative process kept rolling on. “There are parts on this album that were recorded a year apart from each other,” says Portnoy, “and we’re still literally making tweaks, because there’s a 5.1 mix which we call the Ultimate version which actually combines both [parts]. It’s like 100-minute version of the album, which has everything and the kitchen sink, so that’s really a third version.”

As if three versions of the music wasn’t sufficiently lofty in ambition, Portnoy and mixer Rich Mouser have been kept busy editing tracks for promo videos. “It’s a never-ending process,” says the drummer. “This project is like the project that will just never end.”

On that note, there’s a frisson that accompanies each new Transatlantic album because they happen so rarely. “You have four guys that don’t always agree, in fact we rarely agree to be honest, but that’s what makes it so good in the end, because we all really care,” says Portnoy. “We want Transatlantic to be something that people have to look forward to, you don’t just get it every year like a normal, full-time band. I think that makes it special and makes what we do so appreciated by the fans because they know when they do get it, it’s going to be special.”

“It was a long process, but it was worthwhile,” says Trewavas. “I’m very excited about it. We’re all really proud of this one. If it’s not the best thing we’ve done, it’s pretty damn close.”

This article originally appeared in issue 116 of Prog Magazine.