Two Americans, and Englishman and a Swede walked into a recording studio... no, it’s no joke: it’s the ‘blind date’ that created the supergroup Transatlantic in 1999. With three albums under their collective belt by 2014, The members told Prog about their fourth, that year’s Kaleidoscope.

Call them outrageous exercises in collective self-indulgence. Call them bloated vanity projects designed to generate easy money. Call them grand follies that rarely deliver the expected sum of their parts. In fact, call supergroups whatever you like, because the reality is that there’s something inherently thrilling, fascinating and untamed about the potential that shimmers on the horizon when famous musicians from different parts of the sonic spectrum join forces to make fresh sounds for our entertainment.

From Cream and Blind Faith to U.K. and Asia and on to the subject of this story, the none-more-prog superhero formation that is Transatlantic: such supergroups have been an integral part of the rock’n’roll firmament for as long as guitars have been loud enough to make our ears ring.

And of all genres, progressive rock has long been the most suitable breeding ground for such extravagant ventures. High standards of musicianship, refined creative expertise and an unerring knack for bringing preposterous flights of musical fancy to vivid life are the veritable bread and butter of prog.

And so when four musicians of the indubitable calibre and clout of Neal Morse, Mike Portnoy, Pete Trewavas and Roine Stolt first pooled their artistic brilliance back in 1999, devotees of adventurous rock music nearly drowned in a tsunami of expectant froth.

Gratifyingly, it seems reasonable to say that unlike many other similarly ambitious projects, Transatlantic have consistently delivered the goods ever since their genesis. Their latest – and maybe even greatest – studio album, the many-splendoured Kaleidoscope, sustains the purity, humility and sense of honest endeavour that brought them together in the first place.

“It does feel a bit ridiculous to be labelled a supergroup at all!” laughs Pete Trewavas. “I thought Emerson Lake & Palmer were a supergroup and I think Cream were too, but we’re just... a collection of people! That’s still how I see it. I don’t really see myself as the sort of person that warrants the label ‘supergroup’ anyway. Maybe I’m being a bit too English, though!”

“People can call it a supergroup if they want,” shrugs Mike Portnoy. “I think we’re able to do this and keep doing it because, at least when we formed this band, we were able to make this an outlet where anything goes. I honestly think that out of every band that’s out there right now Transatlantic is the ultimate example of progressive music in the classic sense being done today.

“If I wasn’t in Transatlantic, this band would be my favourite prog band! We have the long, epic songs, the big, glorious, majestic themes, the musicianship, the incredibly memorable melodic sensibilities. For me, it encompasses everything I love about prog, supergroup or not!”

Perhaps it was Portnoy’s initial motivation for assembling this crack team of prog notables that saved it from becoming just another clumsy vanity project. In truth, however, it is only recently that Transatlantic have begun to give the clear impression that they are more than just a diverting side-project to keep themselves occupied in rare lulls between the more frenzied activities of their, dare we say it, proper bands: Marillion for Trewavas, of course; The Flower Kings for Stolt; various solo excursions and (formerly) Spock’s Beard for Morse and something in the region of 273 ongoing musical projects for Portnoy.

Instead, Transatlantic in 2014 look, sound and behave very much like a proper band. Prompted by Neal Morse’s well-documented spiritual revelations and subsequent conversion to Christianity, the eight-year gap between their first two albums – SMPTe and Bridge Across Forever – and the third, The Whirlwind, not only increased the band’s collective passion for making music together, but also seems to have cemented their united belief that Transatlantic is a living, breathing band in its own right, rather than just something to fill up the rare spaces in their calendar when their more regular musical duties have temporarily fizzled out.

“Yes, I think I heard Mike mention that this feels like a real band now,” agrees Roine Stolt. “We used to be a project and now we’re a band, but I don’t know what that means! What is a band? All the guys are in other bands too, but we can’t just leave those bands and say ‘I’m going away to play with Transatlantic for a year!’ There’s a lot to take into consideration, but since The Whirlwind, we’ve been trying to get together again, because this feels like something we all need to do.”

“We are pretty busy people and some of us ridiculously so!” Pete adds. “I don’t know when Mike sleeps, to be honest! At first this was just a project. The first two albums felt much more like that, certainly. But The Whirlwind really changed what we felt we could achieve and there’s much more of a band feel now.”

“It’s crazy, when I think back to when we shook hands in the lobby of the studio in New York where we made the SMPTe album,” Neal Morse recalls. “I think that record was made in five days... or less! I just remember it was very quick. My kids were little tiny things back then and we drove the family minivan all the way up there and camped out at some motel. It’s amazing what’s happened since then and I’m really thankful that we’re still here today. We’re all very blessed to be in this band, I think.”

The difference between supergroups that endure and evolve and those that spontaneously combust seems to be a simple matter of whether or not some kind of creative harmony is achieved between everyone involved. Whether they admit to it or not, most musicians have sizeable egos and in most cases are also very much used to their own ways of doing things. With Transatlantic this is demonstrably the case: certainly, Roine, Mike and Neal have all, at one time, been sitting squarely in the driving seat in their respective full-time bands.

And yet, seemingly against the odds, there is a very audible and exhilarating chemistry between these musicians that strongly suggests that Transatlantic are seldom to be found bickering about who is in charge. This band flows together like tributary streams entering one vast, powerful river. Either that or they have made some kind of pact to leave their individual control freak tendencies at the front door of the studio.

“I would say the bottom line is probably that what you have is four guys, really creative people, getting together and trying to write and create a new album,” states Roine. “It is what it is. Sometimes it’s four big egos in a room, but sometimes it’s four guys that really want to leave everything open and see what the other guys think. It’s a very dynamic process, I would say. I couldn’t really see it happening in a different way than it does. It’s always stimulating to play with these great musicians.”

“It’s heaven and it’s hell. It’s a blessing and a curse!” chuckles Neal. “It’s a blessing when you bring some music to the table and the other three guys love it and take it somewhere, maybe even further than where you thought it could ever go. Then you’re on the mountaintop, man!

“Then there’s other times when you might bring something in and someone says ‘Oh, we don’t really like those chords!’ and then you feel like they’re hacking up your child! It’s like ‘Wow, this thing was really nice and just right the way it was, but look what they’ve done to my song!’ But the real freedom for me has come in trusting that it will all work out for the best.”

Far more than just a casual combination of four famous players’ established trademarks, the music on Kaleidoscope – as was also the case on its three predecessors – effortlessly raises the bar for classic prog rock, embracing both cherished old school values and the sustaining pulse of gleaming modernity, while also hurling countless irresistible melodies and moments of balls-out rock bravado into that bubbling cauldron of impeccable performances.

At times, particularly on the new album’s two vast epics – the opening Into The Blue and the closing title track – the sublime efficacy of the quartet’s musical prowess and songwriting skill borders on overwhelming. At others, this is manifestly a band who have mastered the art of subtlety as comprehensively as they have the art of bombast.

“All I can say is that the guys are all just... sickly talented! It’s sick!” says Morse, hooting with elation. “Once we’ve got the stuff written how we want it and arranged how we want it, it’s totally sick how fast Mike does his parts. I think he did all his drum parts on The Whirlwind album in one day. When he starts rolling it’s like a freight train and everybody better get out of the way. It’s really amazing. But there are no slouches in this group. This is an amazing bunch of guys.”

“The creative process starts in advance and then when we’re together it’s fast and furious,” adds Pete Trewavas. “We battle through each other’s ideas, we see what’s going to work and see what fits and then we demo it quickly. We took about two or three days to demo this album and then we set about recording the drums and bass.

“All in all we took about 10 days to achieve that. Then Neal put keys and vocals on at his home studio, Roine went home and put on guitars and loads of other stuff. We probably all record too much and then poor old Rich Mouser, who mixes the stuff, has to try make it all magical for us. He makes us sound better than we really are, I guess!”

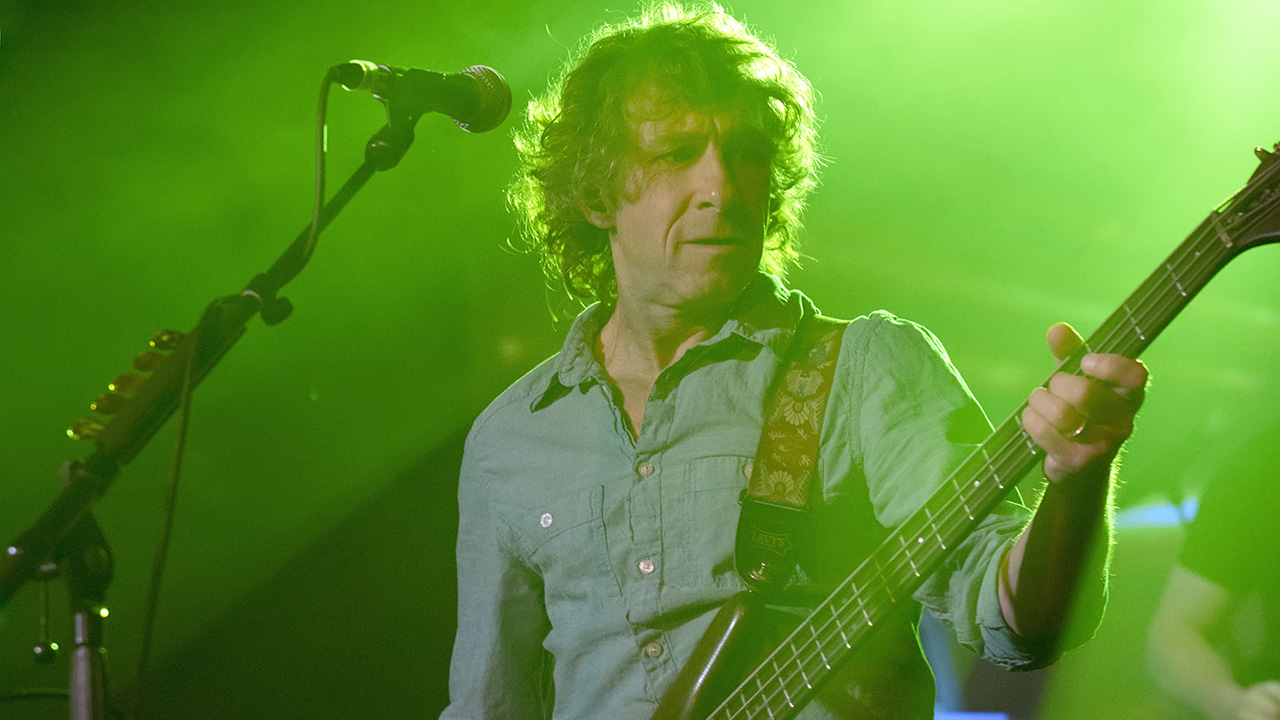

Despite Trewavas’ endearing modesty, Kaleidoscope is very plainly the work of some serious virtuosos, all well versed in the science of knowing what to play and what not to play. In truth, we should probably expect the Marillion bassist to be the most modest member of Transatlantic, comfortable as he surely is with his perennial role as the rhythmic and melodic backbone, rather than someone likely to burst into a dizzying solo at any point in a song.

Tellingly, however, his bandmates are all equally insistent that Pete’s contribution to Kaleidoscope is as significant and vital as any other. “I give Pete all the credit in the world,” says Portnoy. “I think the stuff he does with Transatlantic is his greatest recorded performance – and that’s saying a lot because I’m a huge Marillion fan. They have such a ridiculously large catalogue of music, but he has to have a degree of restraint with Marillion which is appropriate for them. in Transatlantic he’s just able to let it fly, and he really kills it each and every time.”

“I usually refer to Pete as the unsung hero of the band,” concurs Roine Stolt. “What Mike can play on the drums is really well documented and Neal is a really good keyboard player and guitar player; but in the case of Pete, I say he is the absolutely best bass player I’ve played with and one of my favourite bass players of all time. The technical skill of the stuff he’s playing... well, some of it I can’t even play on the guitar! It’s true! He is very underrated, I would say.”

A wonderfully focused and yet deliciously sprawling explosion of exquisite prog derring-do, Kaleidoscope swiftly answers the obvious question: ‘How the hell are Transatlantic going to top The Whirlwind?’ Not everyone will necessarily agree that the band have raised the bar beyond the mind-blowing depth and detail of 2009’s 78-minute masterwork; however, Kaleidoscope takes the listener on a wholly new and equally fantastic voyage, something that Portnoy puts down to a simple case of different times conjuring different ideas.

“Every time we’ve made one of these records we’ve had different circumstances,” he explains. “First time around it was a blind date. We’d never met each other or worked together, so there was a lot of nervous energy. The second record, we were coming off of touring together and getting to know each other, so it was the first time making a record with an existing chemistry. The Whirlwind was big reunion after a big hiatus, and Kaleidoscope was like, ‘Here we are, we’ve been doing this for 14 years so let’s just do what we do.’”

“The Whirlwind had a lot of variation but it had a couple more songs that were more mainstream prog; this one is more hardcore prog, as I see it,” adds Roine. “I can’t say if that’s a good or bad thing! In terms of commercial sales, it’s maybe a good thing if it has more commercial songs, but maybe the fans are really hoping that we’ll go in this direction and be a little less mainstream. Either way, this could only be Transatlantic – no other band.”

The sheer audacity on display during parts of Kaleidoscope seems certain to delight anyone who likes their prog with a large helping of wilful complexity, but one of the key factors that has propelled Transatlantic to the pinnacle of the modern prog tree is the way in which they seem always able to grace even their most elaborate arrangements with soaring melodies that aim to tug at the heartstrings and make the spirit soar.

On this album, the three songs that nestle snugly between those two epic bookends are as incisive and infectious as anything in any of the musicians’ respective catalogues (or indeed their own collective one). Of the three, it is the heartbreaking elegance and fragility of Beyond The Sun that stands out the most; not least because its stripped down arrangement offers a sense of space and restraint that contrasts powerfully with the brazen intricacy and blurred finger bedlam that dominates elsewhere.

Arguably one of the most beautiful songs that Neal Morse has ever sung, it’s a song with a big heart and yet more proof that Transatlantic are a band that answer only to the music itself. “I was flying last May to do some concerts in Canada and I was on a little propeller plane between Toronto and Quebec City,” Morse says of the song’s genesis. “I just sat on the aeroplane, thinking of my father and how The Whirlwind was made two weeks after he passed away. I wrote Rose Colored Glasses for my dad on that album. Thinking about that brought Beyond The Sun into my mind and I was thinking about seeing him again.

“In fact, it was originally supposed to be an intro for the album, but it was too long. Roine and I laboured to have it end on the same chord as the one at the beginning of the song Kaleidoscope. Mike wanted it to be its own track and that was fine with me. I like it a lot.”

If any further evidence is needed that Transatlantic are a supergroup like no other, it is worth noting that the lyrics on Kaleidoscope are a truly collaborative effort. With all four members of the band contributing vocals, it only seems fitting that lyrical duties should be divided up in a similar way, but it is a testament to the way that these four major prog alumni interact that a song like Into The Blue contains distinct contributions from several members of the band, with each bringing their own individual perspective and thoughts: a veritable kaleidoscope of sentiment and semantics, if you will.

Veering from Neal Morse’s trademark musings on spiritual affairs to the considerably spikier, politically tinged observations of Roine Stolt within a few sumptuous minutes, Transatlantic are a truly four-headed beast with all the depth and breadth of personality that such a collaborative free-for-all should rightfully entail.

“We’re all writing from completely different points of view,” Roine explains. “Neal and I were both writing about things we felt strongly about. I was going more in a political direction, whereas Neal was going more towards the spirit of things or his religious feelings.

“When Paul McCartney and John Lennon wrote A Day In The Life, they had two different songs, put them together and it made sense. It’s like the human mind. Sometimes your thoughts are scattered, fragments of thoughts, and that’s what we put into the music. It shouldn’t work but somehow it does. That’s the magic of music, I’d say.”

Therein lies the secret to Transatlantic, this towering supergroup that both refines and defines progressive rock in the 21st century. Four amazing musicians, four distinctive styles and approaches, four unique visions colliding. It shouldn’t work, but it does.

“You never know which way the Transatlantic ship will turn,” concludes Morse. “We’ve said that a lot of times and I think it’s true. I don’t have a crystal ball so I don’t know what’ll happen next. We bring out the best in each other – iron sharpens iron, man, you know? We get together and we sharpen each other. And right now we’re really sharp!”