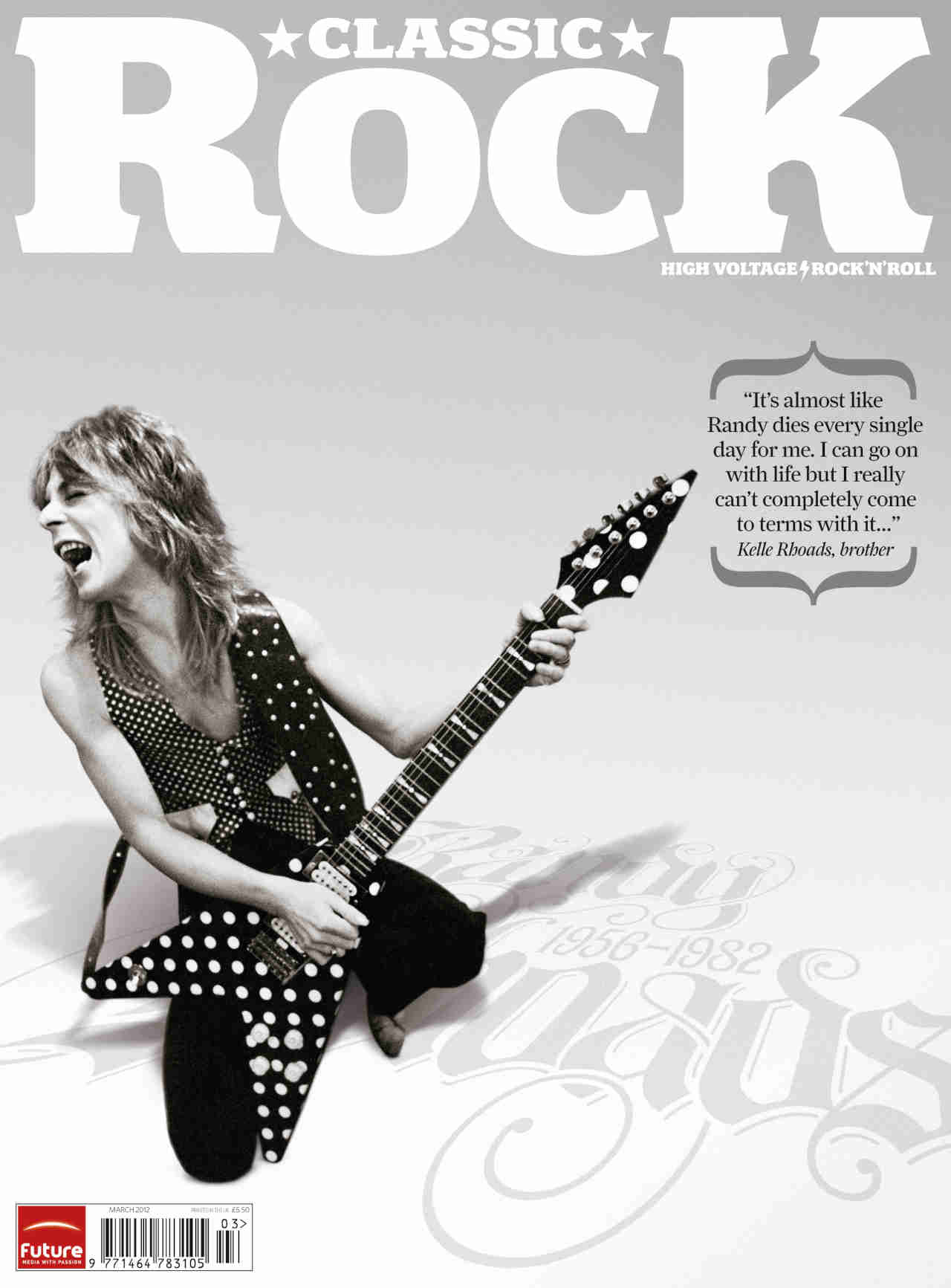

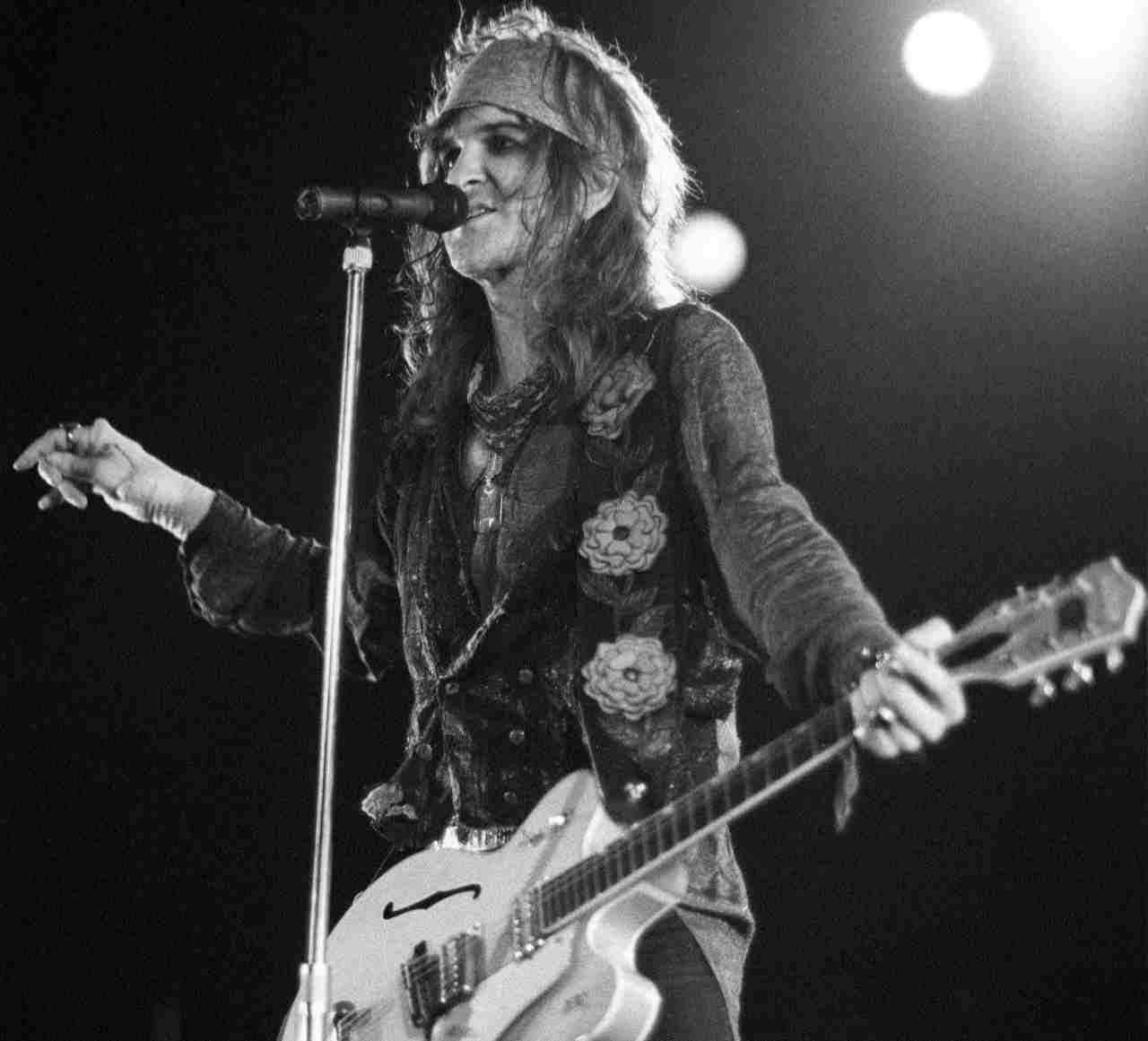

Cult rock’n’rollers Dogs D’Amour emerged from the scuzz of late 80s London like a bunch of rock’n’roll vagabonds. For frontman and pirate-in-chief Tyla, it was the start of a journey that saw him become rock’s own answer to Charles Bukowski. In 2011, he sat down with Classic Rock to look back over his unique career.

Arms high and wide, Tyla is recreating the moment nearly 21 years ago when he cut open his chest with a broken bottle onstage at the Florentine Gardens on Hollywood Boulevard. It wasn’t the first time he’d done something like this, but this time he had pushed the jagged glass in too deep.

“I misjudged it,” he says. “I was doing angel dust at that point, and I just went: ‘Let’s fucking play’ and slashed myself. I threw my arms up, which didn’t help, and then the wound really opened up.”

You can go online and find a clip of the incident , if you’ve got a strong stomach. It was October 1991, and Tyla’s band, the Dogs D’Amour, were a combustible live outfit who were attempting to translate their UK success into a Stateside buzz. They were holding the Florentine Gardens audience in their thrall, and were part way through the song Back On The Juice when the singer decided to take the bottle to his torso. The footage shows his chest flapping open, a bloody maw. A hint of realisation that something is amiss appears in his eyes, before he collapses onto the stage.

It says something about Tyla’s charisma that even while slumped unconscious on a gurney, waiting to be wheeled into the back of an ambulance, three different girls all claimed independently to be his wife and demanded that the medical crew take them to the hospital so that they could be at the singer’s side when he came to. The crew, quite sensibly, ignored the tear-stained trio, leaving them sitting on the sidewalk, staring miserably at the departing revolving red lights as the mercy wagon sped off into the Hollywood night.

At the hospital, the doctors staunched the bleeding and closed his chest up, but his travails weren’t over. “I had all these staples in holding me together,” he explains. “A few weeks later, the doctor was using a clip to take them out, and he slipped and they all opened up at once. It made this ripping sound, and my whole body just sort of shook and came apart again.” He cackles at the memory.

Tyla has come a long way from drug-induced self-mutilation, though his charisma remains undimmed. Sitting in the corner of a North London pub, he stands out from the pre-Christmas shoppers slowly filling it up: black pinstriped suit and cap, crow-coloured hair touching his shoulders, a beard that makes him look like he’s been castaway with Johnny Depp and his Pirates Of The Caribbean. His voice is a low burr that occasionally pitches sideways into a distinct Wolverhampton twang. A pint of Guinness sits before him; later he’ll finish half of it in one long gulp. He puts you in mind of a character from a Tom Waits song who’s surprised to find he’s lived so long.

He’s frequently taken the road less travelled during a 30-year-career that has propelled him from the promise and chaos of the Dogs D’Amour to a solo career-cum-cottage industry. As befits a man who adores Pablo Picasso, Charles Bukowski and maverick Be Bop Deluxe mainman Bill Nelson, he sits outside of the mainstream, surviving and thrived where many of his peers have fallen by the wayside. He is, in the words of one his own songs, the last bandit.

Tyla first saw the future from the balcony of the Wolverhampton Civic Hall. He was 14 years old and the band were Be Bop Deluxe, who were touring their then brand new album Modern Music. They were the first live band he’d ever seen.

“They had suits on, they looked so cool,” he says, “I went out and bought Modern Music, Futurama and Sunburst Finish all at the same time. People used to go on about how the Dogs were influenced by the Faces and Stones, but for me it was Bill Nelson, Bowie, Lizzy and stuff like the Spencer Davies Group.”

The young Tyla’s dad was a printer who brought home reams of paper for his son to draw on. He went from mimicking the Topper comic to aping his artistic heroes, Picasso and Dali, before finding his own inimitable style.

It was also his dad who got him his first guitar. He learned to play that dusty old parlour song Beautiful Dreamer, but what he really wanted to play was Jailbreak. When a friend showed him how to do exactly that, Tyla discovered a hitherto hidden musical talent. By his late teens, he was an ardent fan of old time bluesmen like Muddy Waters and Lightnin’ Hopkins. It was inevitable he’d form a band sooner rather than later; when he did, it was with fellow Black Country native and future Killing Joke bassist Paul Raven. The band were called Kitsch, after Tyla’s day job as a kitchen porter.

“We were all going to have these different looks,” he says with a grin. “I was going to dress up as a fencer. I was into (Pierrot-costumed SAHB guitarist) Zal Cleminson at the time, and thought: ‘If he can do that then I can dress like a fencer with my rapier!’”

Mercifully, that never came to pass. Instead, by 1983 Tyla had left Kitsch to form a band called The Bordello Boys, who soon changed their name to the Dogs D’Amour. In the earliest days he was just the guitarist; the singer was a transplaneted American named Ned Christie (real name Robert Stoddard, and a future singer in an early incarnation of LA Guns). It was a short-lived union, although Christie did turn his bandmate on to Charles Bukowski. At the time, Tyla was living in a small room at the top of an old house off the Portobello Road in West London; he was 22 and developing quickly as a songwriter. He found a flood damaged acoustic guitar just around the corner: the back was off and it only had three strings, but it was still a bargain at 10 quid. He taught himself to play slide on it and write prodigiously. Bukowski’s poems and stories about life as a down at heel, drunk laureate, detailing lost love and the drudgery of the everyday, were an inspiration for the aspiring artist and writer.

“Ned gave me a copy of [Bukowski’s 1975 novel] Factotum and said: ‘This guy’s just like you’,” says Tyla. “I read it and was blown away. It was: ‘This is day-to-day, just a normal life like I’m living.’ I wrote How Do You Fall In Love Again in this little room. I went on a roll after that.”

Christie was gone within a year, and Tyla took over as the band’s singer, albeit reluctantly, in time for the band to record their debut album, The State We’re In for Finnish indie Kumibeat. Opening for the likes of Johnny Thunders at a time when London was enraptured by anything in cowboy boots and bandanas, the Dogs’ wasted-vagabond look was a hit. Despite this the next few years would be a series of frustrating near-misses with various labels, while band members came and went.

Eventually, in 1988, the band signed a deal with China. By this time, Tyla and bassist Steve James were living in a flat in Kentish Town. Their living room could barely contain the pool table they’d bought, and which Tyla used as an easel to create his band’s artwork. “I was so drunk when I did them,” he says. “I look back and think: ‘That’s terrible’. I have to redo the hands so they look normal. The thumbs are everywhere.”

Though they were all hardened drinkers, it was the singer who led the way in chemical consumption. “No one was ever really mega into drugs apart from me,” he says. “I was never addicted, but any drug coming along I’d take. I was into anything and everything. It wasn’t a self-destruct thing. It either closed the door on my mind or opened one up.”

Their extra curricular activities didn’t get in the way of their work rate. The band’s first album for China, the charming, ramshackle rock’n’roll of 1988’s In The Dynamite Jet Saloon, spawned a minor hit single and live favourite in How Come It Never Rains. The following year’s acoustic mini-album A Graveyard Of Empty Bottles and full-length follow-up Errol Flynn – the latter arguably their best album – sealed their status as the kings of vagabond rock’n’roll. By the time 1989 single Satellite Kid staggered into the Top 30, the band had made the inevitable move to Los Angeles.

“We’d played there and had a taste for it,” he recalls. “But I was the only one who had any cash, as I wrote the songs and no one was on a retainer. I was getting all the attention too. I’m not sure that helped the mood in the band.”

The band arrived in California in the middle of what turned out to be glam metal’s last hurrah. The two biggest-selling new bands of 1990 were Slaughter and Firehouse, but the Dogs were a world away from that. But while they never felt part of any scene, their shows were selling out (one early US tour found them supported by one Mother Love Bone) and Errol Flynn – renamed King Of Thieves in America for legal reasons – had done good business. The new location hadn’t slowed down the band’s prodigious work rate, and they were keen to start work on their next album, Straight??!!. Their label pulled in the requisite big name producer – in this case, Ric Browde, who had overseen Poison’s multi-platinum debut.

“It cost a fortune to make, like £300,000,” says Tyla, partly exasperated and partly resigned. “I think Ric Browde got about 40 grand to produce it. We’d have a knees-up every day. We had these two litre moonshine jugs of Jack and vodka, all laid out for us, and everyday we’d finish them.”

The hangover came when Straight??!! was panned by the press, albeit unfairly. Worse, it failed to even get a release in America thanks to an increasingly sour relationship between China and the band’s US label, Polygram (though it would spawn a series of US appearances that include the infamous chest-slashing show at Florentine Gardens). By the time of 1993’s More Unchartered Heights Of Disgrace, things had sunk even lower – the tidal wave of grunge had washed away everything that came before it, and the album failed to crack the UK Top 30. An offer to support Aerosmith was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

“It was a 100 grand just to get on that tour and we’d just spent 90 grand on …Unchartered,” says Tyla. “We went to China for the money and they just said: ‘No’. So I said: ‘There’s nothing you can do for us anymore, can you just let us go?’ And they said: ‘If that’s the way you feel, yeah’, and we walked off up the road. I remember thinking that someone should have filmed that, us just walking away, because it was the end.”

Tyla had what he calls his first midlife crisis in July 1990, three years before …Unchartered proved to be the Dogs’ last howl. The band were second on the bill to Magnum at the Cumbria Rock Festival, and the singer found himself questioning the reality of his surroundings. “I was like: ‘What the fucking hell am I doing?’,” he says. “ ‘What the hell is this all about, it’s bollocks’.”

He lost it again, years later. “I’d had a rapid rise into the 90s and then a whole 10 years of what… I really don’t know. I think I needed to just walk into a pub and have a pint with my mates, but I didn’t have any mates, because they were all in the band and the band had split up.”

From the outside, he seemed to hold it together. The Dogs D’Amour splintered after Unchartered, though Tyla had tried to keep the band together. In 1994, flush with money from a Japanese deal, he roped them into playing on his debut solo album, The Life & Times Of A Ballad Monger. But subsequent demos weren’t picked up, and Tyla went back to playing solo shows, just him and his acoustic guitar.

“I kept me head down and got on with it,” he says. “I did gig after gig after gig. The outlet for everything for me was my gigs: so I could play there, open up a portfolio of my art and sell that. I gave up waiting for phone calls, waiting for my manager – I went out on my own.”

A gypsy-like lifestyle meant he was always on the move, though he managed to stay still long enough to record the excellent Libertine and Gothic albums (1996 and ’97 respectively) and build up a portfolio of art that entices people on both sides of the Atlantic to this day (he says if he paints ten pictures, then he sells ten pictures). By the end of the decade, he’d settled in Barcelona with his wife, where he became a one-man recording industry, releasing a string of solo albums on his own label, and even reuniting with the Dogs for 2000’s Happy Ever After.

“Even though I was married, my wife at the time and I had separate lives,” he says. “I’d ride my bike around Barcelona, smoking spliffs, and come back and I’d make music. There are some great songs on those albums, but because I did a lot of those with drum machines and in isolation, some people just don’t get it, so I have to go back and do them again and use a real drummer this time.”

He’s already started revisiting his own back catalogue. Last year, he re-recorded the Dogs D’Amour’s In The Dynamite Jet Saloon, and he’s talking about doing the same with A Graveyard Of Empty Bottles and Errol Flynn.

“It’s like Michael Gambon going back to doing all the great Shakespeare roles,” he says. “He said he hadn’t done them right and wants to go back and do them properly, now he knows how to do it. I know how he feels. It’s only in the last few years I’ve pulled my head together to look at some of those songs and go back and decide to do things differently. Most of those songs were written when I’d left somebody or was in a dark place. It was odd to sing some of them again, thinking, what the hell was going on in my life there?”

After his marriage fell apart, Tyla relocated to London. He lives a few miles from the pub we’re in, with his partner Bess (immortalised in song on his latest album, Quinquaginta) and their two kids. These days he makes as much money from his paintings as he does his music: he exhibited in London last year, Munich the year before that (he attended the opening of the latter on crutches, nursing a broken leg, and made the front page of the local paper). This year there’ll be a memoir of sorts, Dog Tales – “epic little stories about my life”, as he puts it.

“I’m having a bit of a renaissance,” he says. “I think it’s because I took a year or so off, rather than keep going out and doing stuff. Also, I actually have a price that I’ll go out for or I won’t do it. Some people go: ‘Fuck off’, some don’t, but you have to draw the line. I’ve got an audience, I’ve got a distribution deal, I’ve got interest from Japan again.”

He smiles wryly. “But I did wake up at five this morning and think: ‘How do you write a song when you’re happy?’.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 168,