This year was supposed to involve a ton of touring. We were supposed to tour with Stone Temple Pilots and Nickelback in America. We were supposed to go over to the UK… That’s one of the biggest bummers about this year, that we’re not going to get to play over there.

Noah [Denney, Shakedown bassist] left the band at the end of February to pursue his passion of being a drummer. He was a drummer before he joined the Shakedown, and he simply missed it. It went as good as it possibly could go. He came to us and said: “I just don’t want you guys not to talk to me. You’re my best friends,” and we all hugged it out like brothers and it’s all good. But that was a little strange too.

Then one day Rebecca [Lovell, Tyler’s wife and Larkin Poe singer/guitarist] and I went over to have dinner with Graham [Whitford, Shakedown guitarist] and Graham’s girl. We were talking about the tornado, which had just happened in Nashville. And then Rebecca and I went to the grocery store and noticed all the toilet paper was gone. I thought: “That’s strange…” The next day, lockdown happened.

March 17

I thought: “This’ll be over in a week.” Which is why Crazy Days [the first single] was written today, at the very top of it [lockdown], not realising it was going to last the majority of the year. At this point I was only having brief moments of wanting to get out and live life the way it was before COVID-19. I love being holed up in my studio.

At the start of the quarantine I was honestly stoked to have an excuse to say no to social events that I had no interest in attending. When I meet people when I’m out touring, they ask: “What’s your favourite place in Nashville?” And I’m always like: “Dude, ask someone else.” I go to the grocery store and I go home.

I’m such a homebody. When I come home I like to sit outside and grill and listen to music and be alone and not have to talk to people. But like most people, I started missing everything. I wrote Crazy Days imagining nights out with my friends, going to concerts, playing concerts etcetera. The song took fifteen minutes to write.

I asked my wife to sing the harmony on the tune, and she blessed my demo with her badass voice. I sent the clip to my friend and longtime collaborator Roger Alan Nichols. He said: “You should put that up.” I didn’t know that my basement demo would end up serving as the catalyst for a new Shakedown record.

March 27

My new pink resonator guitar arrived, and I knew it had songs in it. It ended up all over the record. I got my first resonator guitar when I was fifteen, it was a gift from my father, and I still have it. So I’ve been into them since then because a lot of the blues greats I loved played them.

Then when I was in my early twenties I learned about Chris Whitley, and he quickly became one of my favourite songwriters. He’s probably the reason my wife and I hit it off, because we started sharing Chris Whitley bootlegs and recordings.

Crazy Days was written on an acoustic guitar. I started writing it on the acoustic guitar and I was like: “It sounds kinda country.” But when you play it on a resonator it adds this filth, and I love that.

Whenever we write a song, we record it. So we have hundreds and hundreds of songs just sitting around. Cos when we’re home that’s just what we do. I mean, Graham sent me two recordings yesterday.

April 2

Between the time that Crazy Days was written and April 2, all of our tour dates were cancelled. Sure, the financial aspect of that sucks, but the emotional part of it was the hardest. We spend so much time on the road, we’re like fish out of water when we can’t play shows. I hadn’t been off the road since I was seventeen.

The label, Spinefarm/Snakefarm, called and asked where the video of Crazy Days that I had uploaded was recorded. Apparently it had been circulating around the label and there was some excitement about the tune.

Our manager had actually called us at the start of the year and said: “Maybe you guys should just make a record at home.” Because we were still in the Truth And Lies album cycle, so we weren’t gonna get money from the label to go make a record.

The label asked what we’d think about doing a record at home. We talked to a few people, and realised that to work with the people we wanted we were going to give them all our money and end up with three or four songs.

So we all decided to take a DIY approach and make a record in my home studio. We all agreed to ask Roger Alan Nichols to engineer and co-produce the record with us. I called Roger later that day. He was in.

April 4

We filmed the Ride [single from 2019’s Truth & Lies] video in a total DIY fashion. We pulled the seats out of the band van, loaded in our gear and took a drive. This was just another attempt to try to keep the ball rolling and our sanity intact.

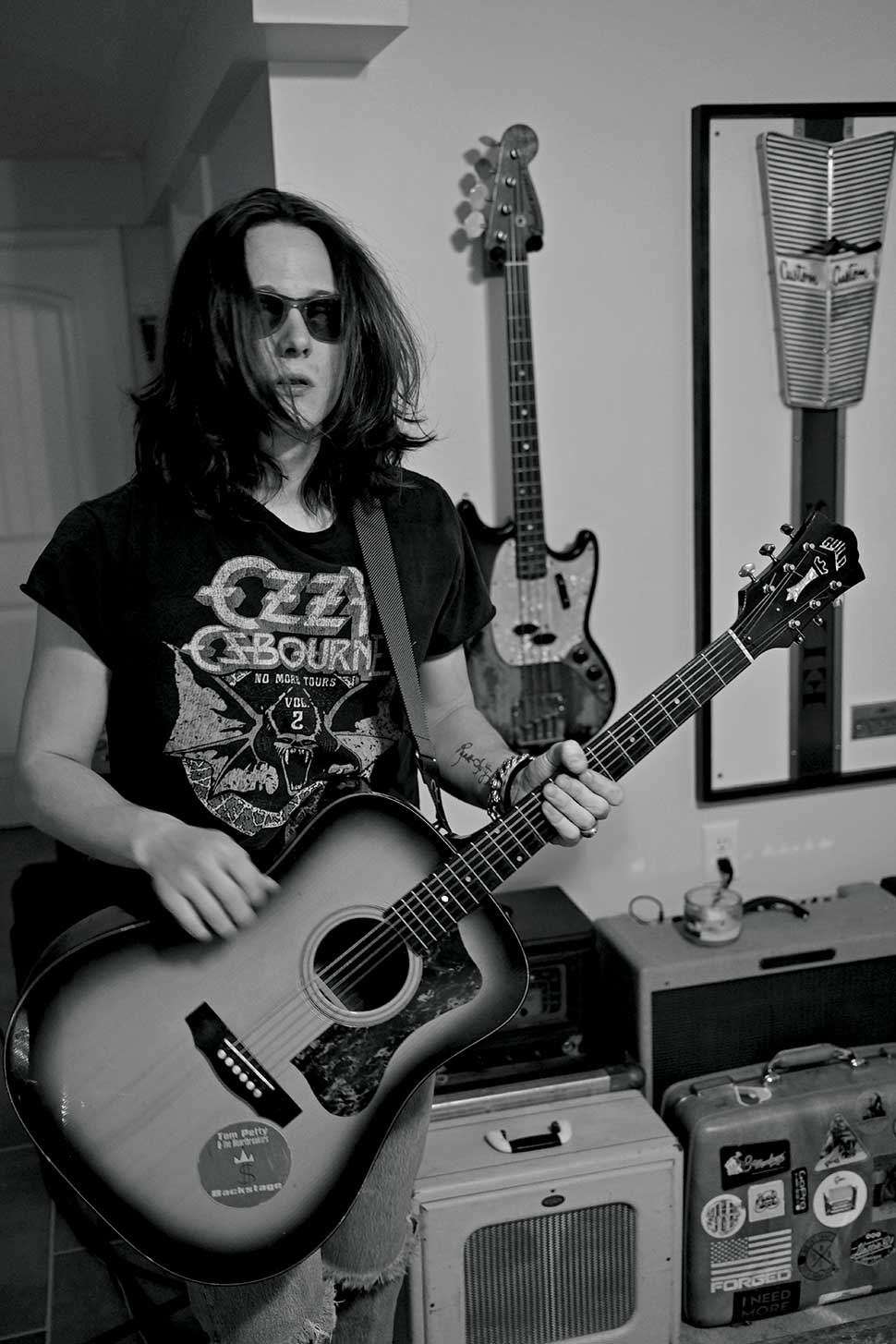

In other attempts I built shelves for all of my guitar cases. I’d walk down in our basement and there’s forty-something guitar cases on the ground, and I was like: “I need to stack these! We’ll have more space!” Stuff like that.

I bought a new grill. I became obsessive about the hedges in the front yard. And I’m doing my neighbours’ hedges every other day…

This is the first full summer I’ve ever had at home in Nashville. It’s been awesome to be able to go outside and take care of my piece of land. It really is quite peaceful to do that, and then come inside and make some music.

April 6

I couldn’t admit it at the time, but I was nervous. Our previous album Truth And Lies had been recorded at a world-class studio in Brooklyn, New York, and we were about to start recording in my house.

Oh yeah, and I needed to pimp my studio if we were going to do this for real. I needed to get a desk that didn’t fall apart every time you leaned on it. We needed more mic stands, all the cabling, better monitors, more preamps etcetera. I started throwing money at gear for my studio and I don’t regret it a bit.

I also reached out to the good people over at Universal Audio on this day about getting a few of the pieces of gear we were going to need. They were incredibly supportive throughout this entire process. Shout-out to companies who are supporting bands. We need that right now.

April 17

I had my studio ready to go. Caleb [Crosby, drums] got his kit set up and we were ready to start placing mics and getting sounds. The whole day was spent dialling in the drums.

Roger was the one saying: “We’re not going to use drum samples. We’re not gonna fix things and do all the things people normally do when they’re making records to make things perfect and precise and competitive with whatever is on the radio at that point in time. We’re gonna make a record in your basement – let it be that.”

We didn’t realise at the time that the limitations we would have during this process would actually serve as a huge source of inspiration.

April 18

This day started off with Graham and I masking up and going to the grocery store to buy provisions. Lunch and dinner breaks would have to be in the studio. We threw a few hundred bucks at sandwich supplies, frozen pizzas and drinks.

I think people probably thought we were doomsday preppers, with the amount we were stocking up on. I had a little amp set up in the kitchen area, and started jamming with Caleb on a song, Fever, that Caleb, Graham, Roger and I had started writing a while back. Roger gave us the green light and we played through the tune twice.

The second take is the one that made the record. It came out raw and edgy and it sounds like us when we are playing live, not like a band that was trying to be on their best behaviour because the tape was rolling. We were off to the races.

April 19

Roger woke up at six a.m. to take the Fever files into his studio to do a rough mix. He came over around eleven a.m. and played it for me. At this moment I realised that we were really gonna pull this thing off. I was like: “Oh my god, I’ve got to get Rebecca, I want her to hear this!” That’s how I know when I like something, if I wanna play it for the people I care about.

I’d met Roger when I was seventeen. He was the first guy in Nashville that said: “Hey dude, I know everyone’s telling you that you’re hot shit. But everybody can play the guitar, you’ve gotta work on the songs, man.” He was kicking my ass as a kid. As a seventeen-year-old, when everyone else was just blowing smoke, he’d say: “Come over, bring your guitar…”

Over the years he and I became great friends. He’s collaborated with us on every Shakedown album, but we’d never had him dive in this deep with us.

April 20

We recorded Automatic. This song was undeniably inspired by all the touring we did with AC/DC and Airbourne. They had the most badass driving songs, and we felt like we needed one of our own. When I think back to those tours, I think about the backstage hangs that we had within the band.

The AC/DC tour was so exciting. When you pick up an instrument as a kid, and you look at magazines with these bands playing to thousands of people and you go: “I wanna do that! I wanna take that ride!” And we got to take the ride, many many times, with our hands in the air screaming, and it was awesome.

‘Too fast to crash’, that’s very much the spirit of the Shakedown. I mean, I remember the first time we came out to the UK we went out to a pub to have dinner, and Caleb pulled out his knife! You have this Kentucky country boy who doesn’t realise that you’re not allowed to do that there! And I didn’t know any better. Someone we were with was like: “Put that away!”

April 22

We recorded Wildside. We’d start at eleven a.m. every day, which means I get down to the studio at seven-thirty or eight a.m. to sing. Roger would say: “I’ll be there at eleven,” and at ten a.m. he’d be sitting in my backyard. We’d work on something through the day, get it to a point where it was ready to have vocals on it, and the band would go home. The next morning I’d come in and the vocals would be done. So for me it was like eight a.m. to midnight, give or take.

April 24

We spent the day working on Loner. I had originally written it around an organ part, so it was a bit of an armwrestling match to figure out how to pull this one off with the Shakedown. We started hitting a wall. It had been a long day, so we decided to call it around ten p.m. and start fresh the next morning.

Graham dipped out to go have dinner with his girl, and Roger was still hanging around. Caleb was behind his kit when I asked him to jam with me. I started playing Coastin’ and he fell right in line. I had written it one of the previous mornings after hearing my wife playing some Junior Kimbrough riffs. It felt so good to just play some blues after a long day of hashing through ideas.

As the record shaped up, we felt like that song would be the perfect way to end it, having opened it with Pressure which is much heavier and more up-tempo. We’re all under a lot of pressure right now, but sometimes you’ve just got to keep coasting.

May 5

With the studio being in my house, I always felt like I was in it. I suppose that’s the danger of doing it the way we did. If folks would leave around eleven p.m., I’d stay up tinkering with stuff. If I love something, then I want more. So it was a case of: “I love making this record, this record is what I live for, let’s do it more.” And so you end up burning the candle at both ends and looking for a third, and then you find the third one and you’re looking for a fourth.

On this particular day I had a few personal things that were bothering me and I also hadn’t gotten enough sleep. I was just pissy, to put it simply. We were having issues with the headphones when we started working on Fuel. However, I didn’t know this.

I was waiting on Caleb to count the song off. We couldn’t see each other and the communication started to break down. I said something along the lines of: “Could you please count off the song?” He couldn’t hear me. I said it again. Still nothing. At this point I’m asking myself: “How hard is it to go: “One-two-three-four”– bang?

Then Caleb says: “Are y’all ready?” I replied sarcastically: “Yeah, whenever you are.” By the time he’d finished saying: “What’s your problem, man?” my pink Strat had hit the ground and I was barrelling towards him screaming: “You’re my problem, man.” I hit a breaking point and was being an asshole.

I stormed up the stairs. I was shaking. There was a lot more to it than just Caleb and I getting at each other. We’re brothers. We do that all the time, and the pot rarely boils over. I was just running myself ragged. Roger came up to see if I wanted to keep working. Of course I wanted to keep working. There was nothing else to do.

I went downstairs and said to Caleb: “Is today the day I kick your ass?” He said: “Let’s go.” We hugged each other hard, talked it out and got back to it. All along, I didn’t realise that his headphones weren’t working. Regardless, I think that angst fuelled the recording of Fuel. That was the only moment in the whole process where the train felt like it was de-railing.

May 8

This was our last day of tracking. We started the day by tearing down the drums and cleaning up the tracking room. It was a sad occasion, and we all questioned if we should just keep going or not.

We set up a chair in place of the drums, and talked over how we wanted [ballad] Like The Old Me to sound. We all agreed that we wanted to keep it raw and true to the way it was written. I had recently shared the song with my Patreon supporters. I did a live video of it, and a few of them had said: “You should put this on the record.”

I played the song a handful of times, and Caleb, Graham and Roger all agreed that one specific take was the one. Roger said it had made him tear up a little bit. I don’t know where that song came from. We had not been over-thinking things, though, and I didn’t want to start down that road.

We ran mic cables upstairs into a room where Rebecca and I have a baby grand piano. Caleb had worked out a beautiful part to play. Hearing him lay that down really hit me. The process was coming to an end.

When Graham was done with his part, Caleb added a subtle synth part. We listened down a few times and called it done. But Roger had one more thing that he wanted to try – we got my wife to come down and add some background vocals to Hitchhiker, so it didn’t sound like so much of a sausage fest.

After that we popped a bottle of champagne, toasted to each other and the record, and listened to everything. The joy I felt is almost indescribable. It was hands-down my favourite recording experience I’ve ever been a part of.

May 29

I texted my good friend [Blackberry Smoke frontman] Charlie Starr and asked him to sing on Holdin’ My Breath, which would go on to be a single. He said yes. I first met Charlie when we were playing at a charity event in Los Angeles called The Boot Ride that some of the guys in Sons Of Anarchy were involved in.

Years later we got asked to tour with Blackberry Smoke, and Charlie and I became fast buddies. We like touring with good people. That’s what’s great about touring with people like Airbourne and Blackberry Smoke and The Cadillac Three.

I’m so happy that the idea of rock stars being these no-good assholes who are hanging out backstage with their groupies… The bands that are dicks are the people that have the most to prove.

The aftermath

My mental health struggled for a second when the record was done, because it did give me a sense of purpose. The record gave me something to direct my energy into, and when that was done it was like: “What do I do now?”

So I’ve been writing, recording and making records with other people. There’s two more records in the can that have been done here in my home studio. I’ve been spending this time learning how to engineer, where to put the mics, what to use, and just experimenting and trying to further my knowledge on making records.

September 3

We received the test pressing of the new album on vinyl. Whenever we’re sitting in a circle and talking about songs or drum sounds or recording takes, you can’t see to that point where you’ll be putting it on a turntable. But it sounded massive. I felt like a kid.