When it comes to a really good prog-related story, Midge Ure's got a corker. “I was once asked to go and meet Rush, with a view to producing them. They were big Ultravox fans. So I flew over to Toronto, and we had a lovely dinner. Then we got round to talking about their album. They asked what my take on it would be, if I were producing. And I said, ‘I would simplify it.’” He laughs heartily. “Suffice to say I was on the plane home the next day! It was fine, though; I had to be honest. They were brilliant players, and we’d have made a great record together…”

What might have been. While Ure recalls his big brother playing Yes’ Roundabout a lot in the house growing up, he muses, “Too many notes, as they said to Mozart in the movie. Though it’s not too many notes at all; it’s just a skill I do not have. I simply couldn’t do what the prog rock guys do. I asked my friend who played drums in a prog band once what it was like, and he said, ‘You count to 19 and a half, then hit a cymbal.’ Tell you what, though,” he adds, “Billy gets very into textures and augmented ninths and integration of classical structures…”

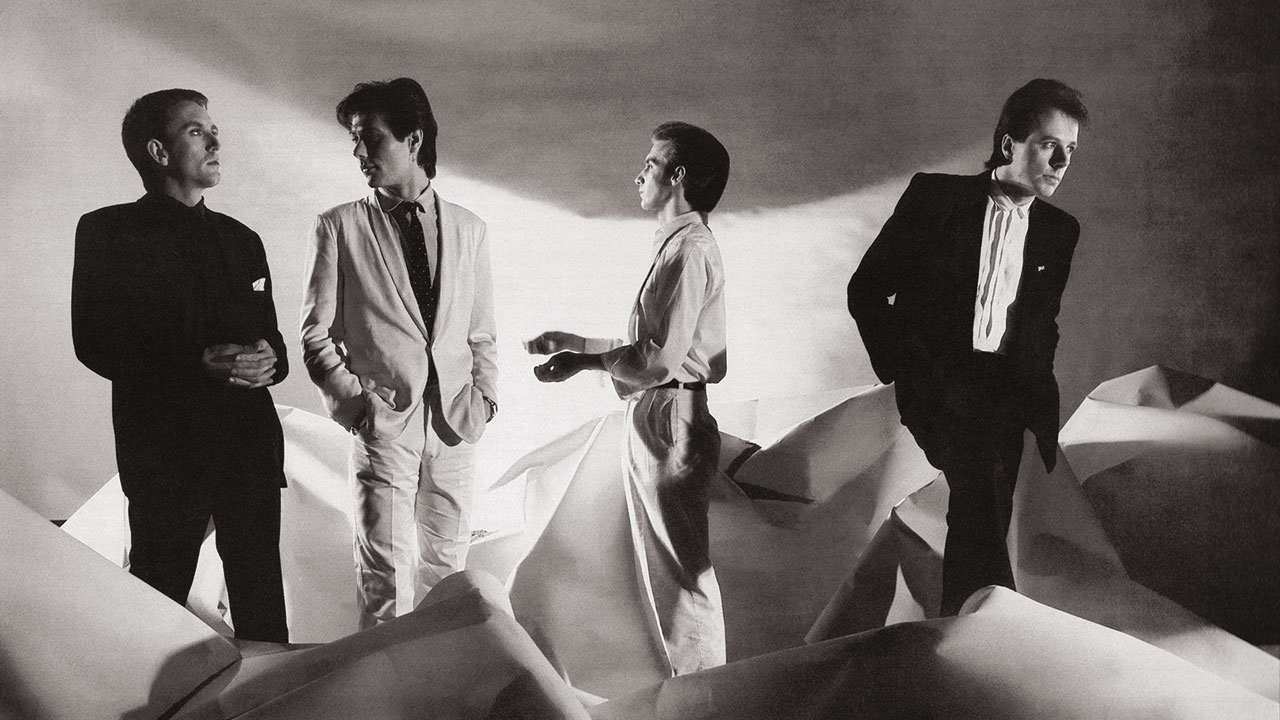

He does, too. Billy Currie and Midge Ure are here to talk about the 40th anniversary deluxe edition of the Vienna album, the band’s commercial breakthrough, usually referred to as a “synthpop classic”. It’s rather more than that narrow definition implies. While it did contribute to breaking the charts’ barriers against synthesisers, and that single became a watershed, it was a profoundly original and forward-thinking record in its own right. From the seven-minute instrumental opener Astradyne to the prescient electro of Mr X, the band were fusing sounds and styles in groundbreaking ways. Alongside the underrated multi-tasking of Chris Cross and Warren Cann, Ure and Currie broadened the vocabulary and palette of rock.

Ultravox had already done something of a Lazarus act. When Island dropped them in ’78 and John Foxx and Robin Simon left, despite the brilliance of the first three albums, they were finding the dawn of the 80s daunting. Currie (violin, viola, keyboards) was playing with Tubeway Army. Ure, nothing if not versatile, had endured, rather than enjoyed, a pop chart topper with Slik, gone on to minor success with Rich Kids, and filled in on guitar on tour for Thin Lizzy. The pair were now collaborating on studio project Visage, a New Romantic concept fronted by Blitz Kid Steve Strange.

“We worked well together in Visage,” says Currie. “That’s why I asked Midge to join Ultravox. This line-up integrated more, pooled our ideas. In retrospect we found our own sound; other ‘electronic’ bands weren’t using ‘real’ instruments alongside synths. At the time I wondered why not. We were so pleased to still be carrying on as a band that we pulled out all the stops, and it was great.”

Chrysalis snapped up the revitalised group, but what’s half-forgotten now is that Vienna itself was only the third single – after Sleepwalk and Passing Strangers – from the 1980 album. And it wasn’t until that came out in January 1981, infamously kept at No.2 by John Lennon’s Woman for one week and Joe Dolce’s Shaddap You Face for three, that album sales soared. “It was gratifying, yes,” says Currie, “but it’s such a strange thing. It’s a miracle it was a success at all! When the label suggested releasing Vienna, I got protective, thinking of it as a great album track, and was saying no… I didn’t want it getting slagged off! Then it goes out of your control, selling 30,000 a day: it’s an odd feeling. Anyway it seems to have stayed in people’s minds, 40 years on, and of course that’s nice to know.”

Back then, Ure was less fazed about replacing Foxx than he was excited about joining a band he thought were “way ahead of the curve. They made the kind of sounds I’d tried to pursue with Rich Kids, but my buying a synthesiser in ’78 had basically broken that band in two. So Rusty Egan and I put together Visage, and

got in one of our favourite musicians – Billy. We’d been playing [third Ultravox album] Systems Of Romance in clubs like the Blitz, and through big speakers that stuff sounded fantastic. I loved what they were doing with technology. And in Ultravox, I was the newbie. Their nucleus was there. I didn’t come in to upset the apple cart, but just by being there I changed the dynamic. So it carried along a line, but there was a marked difference now.”

In New Europeans he sings the immortal line: ‘His modern world revolves around the synthesiser’s song.’ At the time, synths were regarded by some punk rock diehards as the spawn of Satan. It seems laughable now, but late adopters feared synths would destroy us all.

“Oh yes, very much so,” chuckles Ure. “And I remember the early Queen albums had ‘no synthesisers’ on them! It was viewed as a joke instrument, only used for funny effects. And only the German krautrock bands – Can, Kraftwerk, Neu! – were using them in a serious, interesting way…”

“The spacey stuff in the 60s, and even with Pink Floyd in the early 70s, had been the organ,” suggests Currie. “When I first got my hands on a synth, that to me was the future! Its atmospheres were cold and icy. It was mind-boggling!”

Producer Conny Plank had serious form in this field. Ure reveals, “When I joined, the guys had already done Systems Of Romance with Conny. And they were going, ‘Hmm, so who shall we get to produce this one?’ And I was quietly sitting in the corner going, ‘Er, I’d love to work with Conny Plank!’ I was so into learning about production – that’s why I’d put Visage together – and there’s no better way of doing that than being in the room with someone like Conny and learning by osmosis.

“In Britain we rarely heard European music, apart from slabs of Eurovision bubblegum, until [Kraftwerk’s] Autobahn made the charts. And then we started to unravel all these threads. That mixed in with Billy’s classical training – he was pumping a lot of European elements into his chord structures. We had one foot in the future, one in the past, and were trying to make something timeless.”

“And we’d been touring around Europe a lot,” adds Billy. “We were aware of Kraftwerk, we’d picked up on the feel of Europe. Conny opened our minds even more. He’d introduce us to people. Holger Czukay dropped by the studio. And I can still remember Conny playing us Neu! for the first time. I was even checking out Stockhausen. I was into Bartok and Schoenberg. Vienna itself, though, for me, comes from the late 19th century… I still can’t explain why. The decadence, the haunting sophistication of it.”

The success of Vienna was a major factor in synthesisers becoming a regular part of pop music’s fabric. Yet it was that unique blend of what used to be called “authentic” and “artificial” sounds that fleshed out the grandeur of its architecture. As Ure points out, “If you listen to it closely there’s guitar all over it! Because I’m a guitarist first and foremost. And that’s kind of what makes it work – the looseness. Machines didn’t integrate then, didn’t talk to each other. It wasn’t all locked in and absolutely synchronised like it is now. It was played by humans, who are… fluid. So everything was a little off, a little slippy. That’s what a good band does.

“Y’know, everyone says Vienna was an electronic track. And yes, it has electronic drums and a synthesised bass, but it’s mainly piano, violin and viola. Everyone seems to overlook that. Those strange combinations, interactions, made Ultravox what it was.

“Don’t forget everything that was against the band – dropped by the label, in debt – but despite all that we got into this incredibly creative little bubble. I was turning my back on some of my previous stuff; I wanted to be in a band that created interesting stuff I could get my teeth into, and might last. Nobody was more stunned than us when it reached a commercial market. It was beyond anything we’d ever dreamed that something as bizarre as Vienna would do what it did!”

Is it true that as the instrumental of Vienna played in the studio and he was striving to write the lyrics, he said to Plank, “This means nothing to me”?

“That is a Disney-ism!” laughs Ure. “I don’t remember that at all! Hey, maybe it did happen, but… no, it didn’t. That was, in fact, the first line that came to me, along with ‘Oh Vienna’, then we spent four days in the rehearsal studio crafting it.”

“And for me,” adds Currie, “the second side has a trippy vibe. We wanted an old-school feel, segueing between the tracks. It was a worked-out album, y’know? We were moving forward with a slight nod to the past. I’ve got some lovely memories of it.”

Currie’s latest solo album, The Brushwork Oblast, came out in March. Where does Vienna stand, for him, among all the music he’s made?

“It’s probably way up there. I helped [remixer] Steven Wilson on this box set and I’m proud of it. Though I think I peaked on the Quartet album.”

“I think anything so transformational in your life as that has to be considered major,” reflects Ure, whose varied career, from Band Aid to solo success, has been illustrious by any standards. “It happens to you; you have no control over it. It’s a double-edged sword. It elevated the band to big venues, gave us fresh tools – all great. But then everyone expects Vienna 2 or Vienna 3. Which we refused to do. I think the follow-up, again with Conny, Rage In Eden, is a more interesting album. Vienna is a highlight but it’s nowhere near the best song I’ve written, or best piece of music I’ve played. My favourites are usually the ones that got away...”

This article originally appeared in issue 115 of Prog Magazine.