George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four envisioned a dystopian future where totalitarian governments ruled the world and the average person’s attempts to enjoy even the slightest personal pleasure were patrolled and punished by the Thought Police in service of Big Brother. However, when humanity finally reached that symbolic year, the prevailing atmosphere was more of a hedonistic nonstop party than a period of peril. We have the power of the mighty Van Halen to thank for that.

Considered by many – including Eddie Van Halen himself – as the band’s masterpiece, 1984 was one of Van Halen’s best-selling albums and one of the best-selling rock albums of the eighties. It has earned RIAA Diamond certification for surpassing 10 million units sold – a feat the band only matched with their 1978 debut album, with the two perfectly bookending the beginning and end of Van Halen’s classic era with David Lee Roth fronting the band.

Clocking in at a lean 33:22 minutes, 1984 was, as the saying goes, all killer and no filler. Even the best-selling album of all-time, Michael Jackson’s Thriller, can’t make that boast (does anyone even remember Baby Be Mine and The Lady in My Life?). 1984 produced an impressive string of four hit singles, with Jump delivering Van Halen’s only US No.1 charting hit single in the band’s career. Panama and I’ll Wait both peaked at No.13, and Hot For Teacher came in at a not-too-shabby No.56 in the Billboard chart.

Even the album’s deep cuts – Top Jimmy, Drop Dead Legs, Girl Gone Bad and House Of Pain – were scorchers too hot for the Top 40, but found a welcoming home on more adventurous FM station playlists. The only outlier is the album’s title track, but Ed’s solo synth performance perfectly set the mood as a brief overture that boldly introduced Van Halen’s brave new world.

With 40 years of hindsight, it’s tempting to look back and conclude that the phenomenal popularity of 1984 was primarily a result of being the perfect album released at the perfect time. But its success also benefitted from several years of extremely hard work leading up to its release – along with a series of high-profile events that brought Van Halen prominently into the wider public’s awareness.

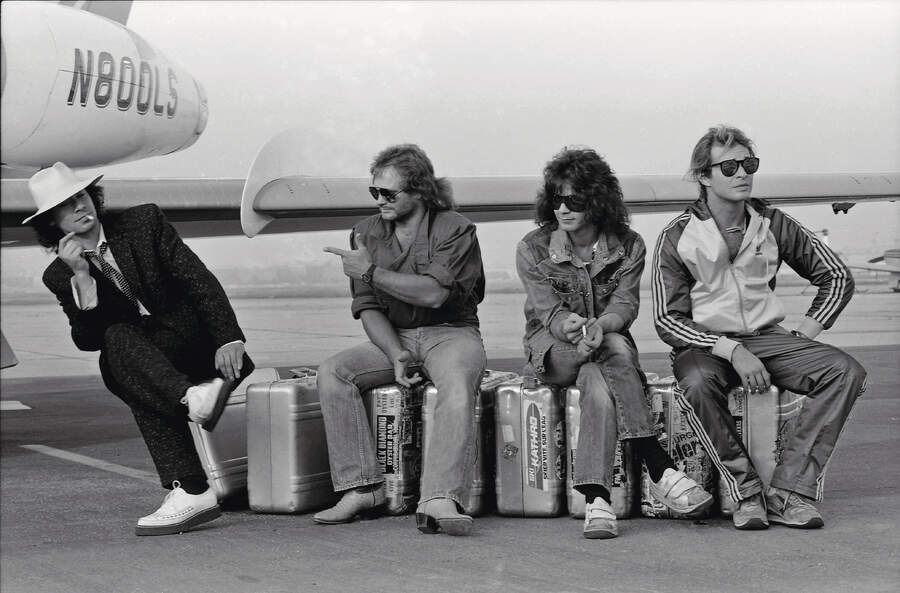

During the early 80s, Van Halen had become one of the world’s biggest touring acts. The band sold out every one of its 83 shows in the United States and Canada on its 1982 Hide Your Sheep tour, and in early 1983 they made their first ever appearances in South America during a month-long leg that introduced the band to thousands of rabid fans.

A few months later, Van Halen staked a claim as the biggest band in the world when they headlined Heavy Metal Day on May 29, 1983, at the US Festival, performing in front of an estimated audience of 375,000 – Van Halen’s largest ever. Their fee for the US Festival gig was $1.5 million, setting a new world record.

The band experienced a significant upward trajectory in record sales. 1984’s predecessor, Diver Down, was a commercial success thanks in large part to the hit status of the 1982 single (Oh) Pretty Woman, which peaked at Number 12 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart.

But what truly catapulted the band into the public limelight was Eddie Van Halen’s increasing celebrity status, even though the guitarist never sought the spotlight and was never comfortable with being called a rock star. His marriage to popular television actress Valerie Bertinelli led to appearances on mainstream prime-time shows like Entertainment Tonight, making the Van Halen name a household word. Ed’s charming, down-to-earth demeanour won over many new fans who would have been shocked by the raucous atmosphere at a typical Van Halen concert, let alone the band’s backstage antics.

But perhaps the biggest turning point that made Ed a bona fide celebrity was his guest appearance on Michael Jackson’s 1982 album Thriller, on Beat It. Jackson wanted to record a rock song, and he knew that getting the world’s most popular guitarist to play a solo would introduce and endear the singer to an entirely new audience. What Ed didn’t realize at the time was that his performance on Thriller would similarly cause Jackson’s fans to notice Van Halen. Beat It went on to top the charts worldwide, and those 33 seconds of guitar shred became an immortal symbol of the most enduring cultural crossover of pop, R&B and rock.

Eddie didn’t want his name to appear on Thriller’s credits, mainly to keep the session a secret from his bandmates, but there was no mistaking who performed that solo.

“Believe it or not,” Ed told Guitar World in 1990, “I did the Michael Jackson thing ’cos I figured nobody’d know. The band for one – Roth and my brother and Mike – they always hated me doing things outside of Van Halen. I just said ‘Fuck, I’ll do it, and no one will ever know.’ So then it comes out and it’s song of the year and everything.”

Despite his request to remain incognito, record company and musician’s union agreements led to his name appearing four times in the liner notes. But it didn’t matter as David Lee Roth immediately knew it was Ed the first time he heard Beat It blaring from a car stereo.

“The new Michael Jackson song, Beat It, came on,” Dave recalled later. “I heard the guitar solo, and thought, now that sounds familiar. Somebody’s ripping off Ed Van Halen’s licks.”

Edward Van Halen’s creative inspiration increasingly grew during the early 80s as he broadened his horizons into new musical styles and techniques and explored instruments beyond the guitar. While he was initially pleased with Van Halen’s fifth album, Diver Down, he wasn’t happy with the rapid-fire approach to the sessions, which were completed in a mad rush over a period of 12 days.

On the band’s previous album, Fair Warning, Ed had finally become comfortable with spending considerably more time recording and crafting multiple guitar tracks in the studio while also experimenting with a broader palette of guitar sounds. He felt that the slam-bang live performance blueprint used on Diver Down was a regression to the band’s first three albums, and the outcome left him creatively unsatisfied.

“I was always butting heads with [producer] Ted Templeman about what makes a good record,” Van Halen said in 2014. “Diver Down was a turning point for me because half of it was cover tunes. When we made Fair Warning I spent a lot more time with [engineer] Donn Landee working on my sound. I became much more involved in the recording process.

"To me, Fair Warning was more true to what I am and what I believe Van Halen is. We’re a hard rock band, and we were an album band. I like odd things. I was not a pop guy, even though I have a good sense of how to write a pop song. When we started work on 1984 I wanted to ram it up Ted’s poop chute and show him that we could make a great record without any cover tunes and do it our way.”

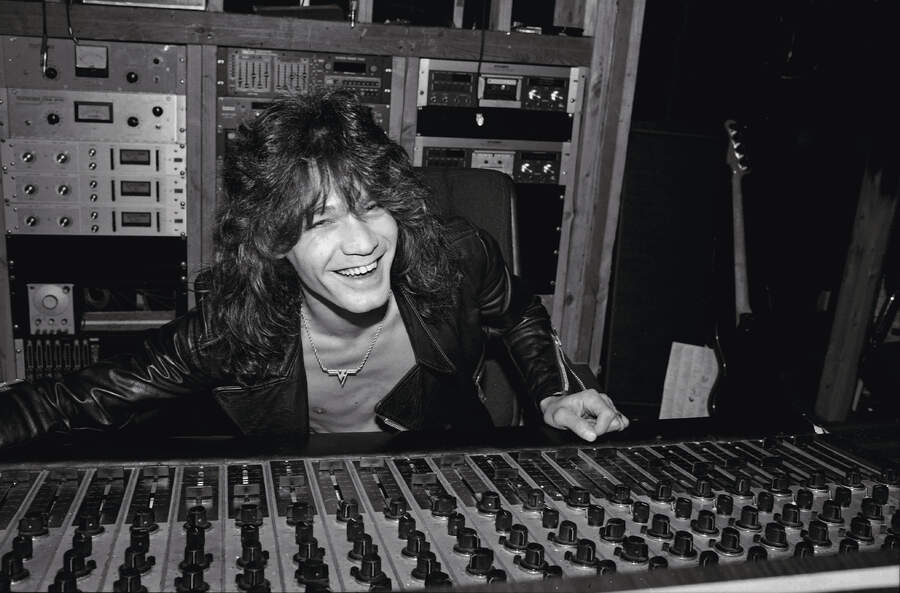

In order to be able to do things his way, Ed took dominant control of the creative reins by building a professional multitrack studio at home in 1982. Initially, the plan was to build a studio for recording demos, but as work progressed the guitarist realized that, with Landee working by his side, he could record Van Halen’s next album there.

“I did not set out to build a full-blown studio,” Ed admitted. “I just wanted a better place to put my music together so I could show it to the guys. I never imagined that it would turn into what it did until we started building it. Slowly it turned into a lot more than I originally envisioned.

"Everybody else was even more surprised than I was, especially Ted. They thought I was just building a little demo room. Then Donn said, ‘No man! We’re going to make records up here!’ Donn and I had grown really close and had a common vision. Everybody was afraid that Donn and I were taking control. Well… yes! That’s exactly what we did, and the results proved that we weren’t idiots.”

Ed’s new home studio, named 5150 after the California law code for taking a mentally disordered person into custody when that person is considered a danger to others, was completed by the end of 1982. In a recent interview with Greg Renoff for Tape Op magazine, Landee recalls that the first recording session took place on January 2, 1983, with Ed on synthesiser and his brother Alex Van Halen on drums.

This was a calculated move on Ed’s part to appease David Lee Roth and Templeman, perhaps hoping to convince them that the studio was indeed up to the task after they worked there and heard the results. The fact that the song was never released and is still locked up in 5150’s vaults suggests that Ed may have never actually wanted to record it in the first place.

However, Ed boldly revealed his hand with his next move. Over the previous few years, the guitarist had worked on a synth-dominated song that would later be named Jump after Roth wrote the lyrics, and with the studio up and running he recorded an instrumental demo of the tune, performed on an Oberheim OB-Xa synthesiser with accompaniment from his brother Alex on drums and Michael Anthony on bass.

“When I first played Jump for the guys nobody wanted to have anything to do with it,” Ed said. “Dave said that I was a guitar hero and I shouldn’t be playing keyboards. But when Ted heard the demo and said it was a stone-cold hit, everyone started to like it more. Ted [Templeman, producer] only cared about Jump. He really didn’t care much about the rest of the record and just wanted that one hit.”

The band worked diligently recording new material there for most of 1983, with the exception of the month of May, which they spent preparing for their appearance at the US Festival. Ed particularly revelled in having “unchained” freedom to experiment whenever and for as long as he pleased.

In addition to equipping 5150 with a solid selection of classic studio gear that included a Universal Audio console purchased from United Western Studios, Ed also added a wide variety of new instruments to his creative arsenal. The musician had become enamoured with the Oberheim OB-Xa polyphonic synthesiser and its updated version the OB-8, and they played a major role in three of the album’s songs.

Keyboards had actually prominently appeared on all three of Van Halen’s previous albums – a Wurlitzer electric piano on And The Cradle Will Rock… (Women And Children First), an ElectroHarmonix Mini-Synthesiser on Saturday Afternoon In The Park and One Foot Out The Door (Fair Warning) and a Mini Moog on Dancing In The Street (Diver Down) – but they were distorted and usually employed as ersatz guitars. With 1984, Jump and I’ll Wait, there was no mistaking that Ed was playing synths.

However, Ed was still a guitarist at heart and to his core, and he made many new additions to his guitar collection. The most notable newcomer was a rare vintage 1958 Gibson Flying V. The V was Van Halen’s primary guitar on the album, used to record Hot For Teacher, Girl Gone Bad, the main riff of Drop Dead Legs and, as recently discovered, quite possibly for Jump.

The guitarist had also acquired a few of Steve Ripley’s stereo guitars, featuring hexaphonic pickups which gave the instrument a very specific sound. Ed put the Ripley to good use on Top Jimmy, using an open D7 tuning and playing harmonics that bounced across the stereo soundscape.

The finished product exceeded all expectations and then some. 1984 was a document of a band at its prime, where years of relentless touring had made their sound tight and their improvisational communication almost psychic. Ed’s songwriting talents had expanded and grown, with his knack for pop hooks balanced by ambitious excursions inspired by progressive rock and fusion jazz.

Perhaps the most surprising element of 1984 is the fact that the first note of guitar is heard after more than two minutes have passed. This was partly the result of Templeman’s late comment that he wished the album had a song called 1984. Engineer Donn Landee realised that he had about 45 minutes of Eddie improvising solo on the Oberheim that could be edited down to an instrumental intro, and voila! He had his wish. The 1984 synth instrumental made the perfect dramatic statement and lead in to Jump.

Jump was pure pop perfection that fit right in with the synth-crazy mid-80s, but Ed’s dynamic guitar solo was the secret weapon behind its success, giving Van Halen a competitive crossover advantage with a hard rock audience that would never be caught dead listening to groups like the Human League, Depeche Mode or Soft Cell. Panama may be the ultimate classic Van Halen tune, with David Lee Roth’s raunchy “fast car and faster girl” lyrics perfectly capturing the SoCal party vibe that made the band so irresistible from day one.

It’s also one of two songs on 1984 that were inspired by AC/DC, which was not a bad move considering how Back In Black had already become the best-selling hard rock album of all-time. The infectious, bouncy energy of Top Jimmy made it a strong contender for a fifth single or at least a hell of a B-side. However, it was probably held back by the difficulty of switching from an open tuning to standard for the solo’s delirious whammy bar workout, which prevented Van Halen from ever performing the song live.

Drop Dead Legs similarly should have been a hit, partly thanks to its relentless pile-driving Michael Anthony/Alex Van Halen rhythm section groove.

“That was inspired by Black In Black,” Eddie admitted. “I was grooving to that beat, although Drop Dead Legs is slower. Whatever I listen to somehow is filtered through me and comes out differently. It’s almost a jazz version of Back In Black – I put a lot more notes in there.” It was never played live until the final 2015 tour.

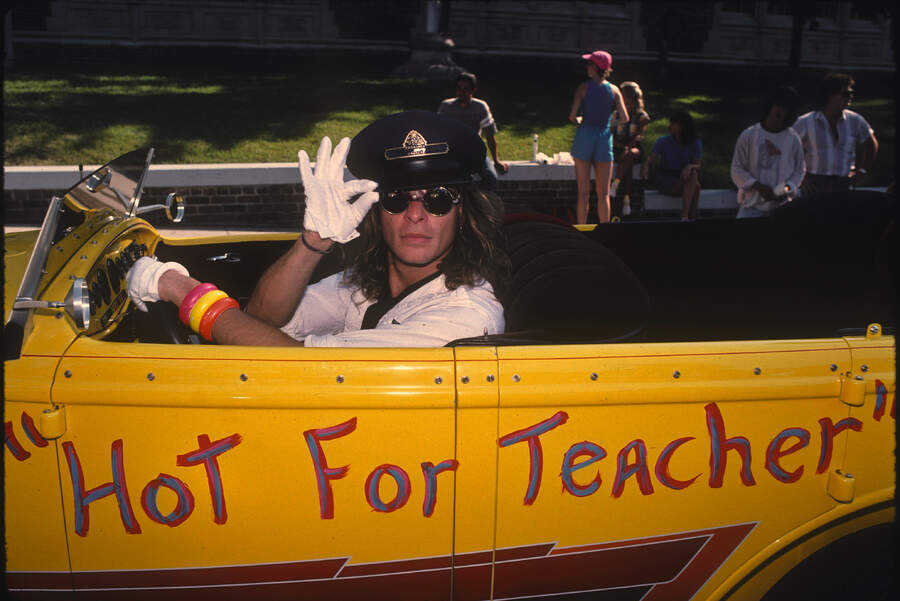

Jump and its supporting music video may have made Van Halen seem harmless and cuddly, but Hot For Teacher was the opposite, exposing the band as the bad boy party animals they really were. Alex Van Halen’s galloping Simmons drum intro sounds like a nitro-fueled dragster revving up before he switches to a Billy Cobham-meets-Buddy Rich swing that pushes Ed’s hot-rodded tapping into overdrive. Roth’s schoolboy-in-heat lyrics are downright horny and given extra punch and verve by Anthony’s high-pitched harmonies, while Ed keeps things loose and raunchy with ZZ Top-inspired bluesy finger-plucked riffs.

I’ll Wait was the album’s other synth-driven hit, with the yin of Ed’s sophisticated keyboard chords and a chorus with smooth yacht-rock lyrics penned by the Doobie Brothers’ Michael McDonald counterbalanced by the yang of Roth’s semi-goofball rants about “heartbreak in overdrive” and “such good photography!” The guitar solo similarly provides a contrast between Ed’s melodic phrasing and fusion-esque flourishes with explosive vibrato bar noise.

When the album’s final sequence was being prepared in late 1983, no one outside the inner circle had any inkling that the band’s classic era with David Lee Roth would soon come to a close, yet the final two songs on 1984 delivered about as perfect a send-off as any fan could ask for. Girl Gone Bad is simply epic and the closest thing to a prog rock song that the band ever recorded. Ed delivered a tour-de-force performance with dynamic shifts in emotion from elegiac tapped harmonics to dark, drama-filled riffs. This was Van Halen’s equivalent to Led Zep’s Achilles Last Stand with the added bonus of a truly blazing Van Halen solo heavily inspired by Allan Holdsworth.

Dating back to Van Halen’s early club days (demos were recorded in 1976 with Gene Simmons and in early 1977 for Warner Bros), House Of Pain was the only song not completely written fresh for the album, although the only element that remained from the early versions was the song’s main riff.

“I guess nobody really liked it the way that it originally was,” Ed said. “The intro and verses are completely different, and the fast part in the middle for the solo and the groove at the end are almost like entirely new songs.”

House Of Pain showed that Van Halen had grown and evolved considerably over the preceding seven to eight years without losing any of their hunger, intensity and power.

All good things must come to an end. They were too good to last. Always leave the people wanting more. These may be overused clichés, but it’s difficult to think of better ways to describe the aftermath of the 1984 album, its ambitious supporting tour and the eventual breakup of Van Halen’s classic David Lee Roth lineup.

Did success spoil Van Halen? Yes, and no. Eddie Van Halen’s ever-growing musical ambitions and desire to pursue different sonic paths collided with David Lee Roth’s incessant adoration of the spotlight and aspirations to pursue a career as a movie star. With two diametrically opposed forces in conflict, the tensions inevitably sucked all the air out of the room until no one could breathe. Trying to outdo 1984’s success would have been an unfathomable challenge for any band, so it sadly made sense for Van Halen to end that chapter at the top of their game.

The Van Halen brothers and Anthony joined forces with Sammy Hagar and his growing legion of fans to take the band in a different and arguably more progressive direction it couldn’t have tried with Roth. The Hagar-led 5150 didn’t reach the staggering commercial sales heights of 1984, but it became Van Halen’s third all-time best-selling album, going six times Platinum. It was also the first Van Halen album to finally reach the No.1 spot on the charts. [1984 likely also would have achieved that feat, but it had the disadvantage of going head-to-head with the best-selling album of all-time, Michael Jackson’s Thriller.]

Meanwhile, Roth put together one of rock’s greatest supergroups, recruiting the extraordinary talents of guitarist Steve Vai, bassist Billy Sheehan and drummer Gregg Bissonette to keep the rip-roaring party going full blast. Roth’s first full-length album Eat ’Em And Smile was nowhere near as commercially successful as the albums he recorded with Van Halen, but with Vai and Sheehan’s instrumental pyrotechnics and Roth’s inimitable character it kept the white-hot flame burning very brightly for classic Van Halen fans.

The split resulted in a David Lee Roth vs. Sammy Hagar argument as incessant as it is meaningless. For some fans, the change was the best of both worlds, but it didn’t last. But it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished. Van Halen had won the victory over itself.