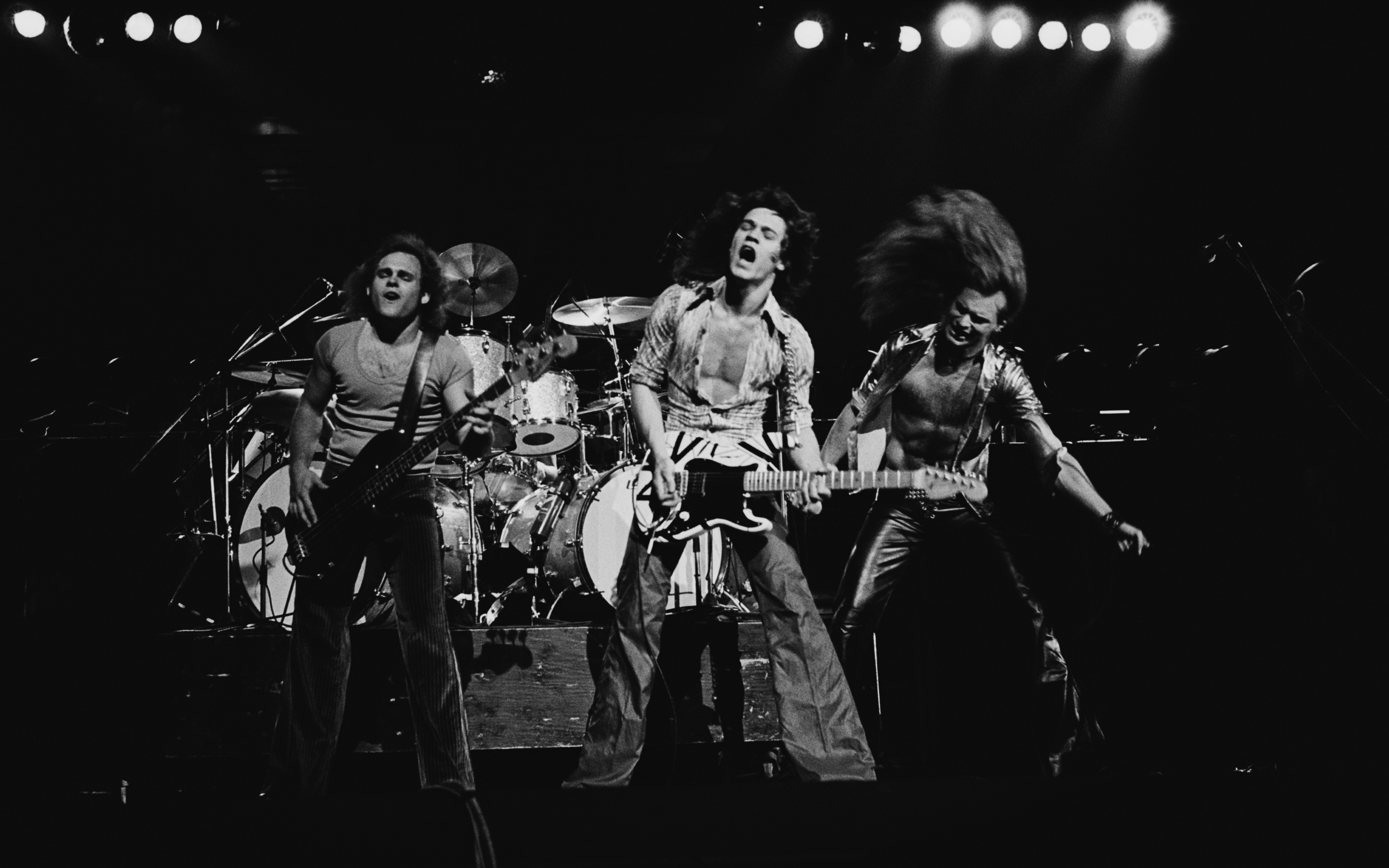

If you were walking down Santa Monica Boulevard in the heart of West Hollywood on a rainy Monday night in early 1977 and happened to glance up at the marquee of the Starwood Club, you’d have seen two band names staring back down at you. The first was that of Yesterday & Today, a straight-ahead hard rock band from up the coast in Northern California who had already released their debut album a year earlier and were headlining a gig that evening.

The second was a quartet from Pasadena, out on the edges of Los Angeles County, who were making a name for themselves in the clubs of LA. They had a reputation as a fearsomely single-minded and ambitious band, but that wasn’t the main attraction. No, the reason why people were talking about them was because they had a guitarist who was truly reinventing what could be done on the instrument, along with an outrageous singer who seemed hellbent on bringing some showbiz to rock’n’roll. The band’s name? Van Halen.

This was one of Van Halen’s first appearances at the Starwood, after graduating from playing Gazzarri’s, a smaller club on the nearby Sunset Strip. Considering it was a weekday night, and given the inclement weather, it was no surprise the club wasn’t even half full – you could have counted the people in attendance on the fingers of two hands.

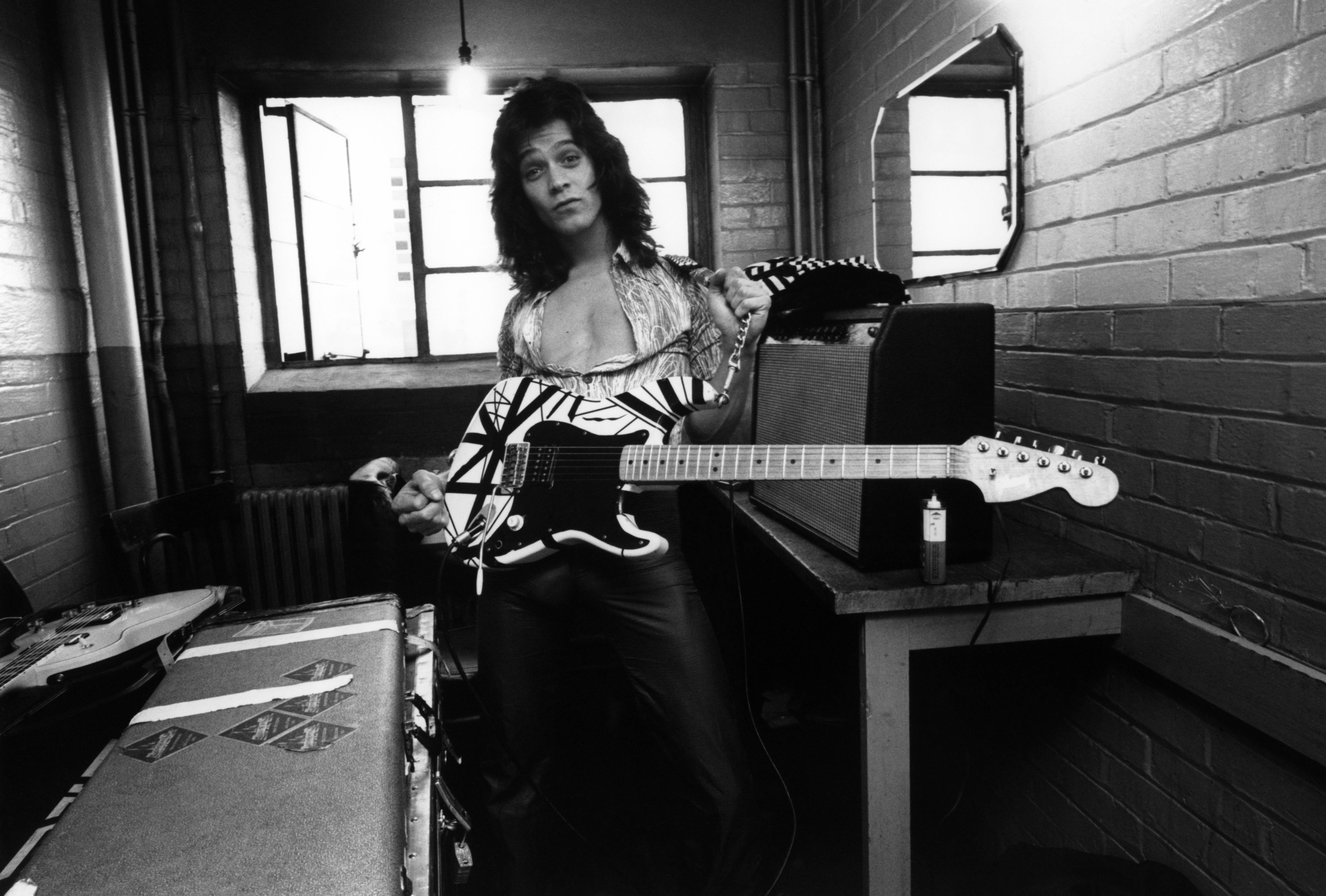

The first time I interviewed Edward Van Halen was in 1978, not long after the band’s debut album was released. He drove to my little guest-house in the Hollywood Hills from his home in Coldwater Canyon, 10 minutes away. The first thing he asked me was: “Do you have a guitar?” I did, a Strat. He spent the whole interview cradling the instrument and working his way through an endless procession of cigarettes.

“I tried playing exactly like some people but I just couldn’t,” he said at one point. “I think that’s how my style developed. Out of the mere fact I couldn’t play like someone else. I had to do something. I had to come up with something myself. I always still look at myself like a kid looking at these guys like they’re big. I just don’t look at myself as equal to them.”

This humility was refreshing – and it certainly must have helped when it came to dealing with the frustrations of Van Halen’s formative years. For a hard rock band, being a fixture on the Sunset Strip rock scene in the mid 70s was a tough job, and landing a record deal required something approaching a miracle. It was an eclectic scene, sure enough – maybe too eclectic.

Musically, things were in a state of flux, fragmenting into disparate but overlapping styles. The glam bands who had risen to local prominence earlier in the decade had put their platform boots back in the closet, and their place had been taken by disco and funk-influenced groups and unruly punk acts. Feather boas were being swapped for skinny ties, and dressing up was passé. In this confluence of styles, maintaining a foothold as a heavy, guitar-driven band required a superhuman determination.

“Bands like Sabbath, Zeppelin and Deep Purple were either defunct or entering the last phases of their career, and classic hard rock was largely a thing of the past,” says Mike Kelley, an habitué of the Sunset Strip scene at the time and someone who saw virtually every gig the band played. “Van Halen, with their arena-rock presentation and Roth’s blatant Jim Dandy/Black Oak Arkansas-clone antics, were a throwback to a bygone era. But despite what appeared to be bad timing, they offered a classic rock’n’roll experience and a new post-Hendrix guitar innovator.”

Van Halen didn’t exist in a vacuum. There was Quiet Riot, A La Carte, The Source, Suite 19 and others. Most of these local bands were friendly towards each other, but competition did exist between them to land the coveted gigs. There were really only four clubs on the Sunset Strip circuit where you could watch their ilk. The Whiskey was the place to go if you wanted to see and be seen, while the Starwood was where you went to party.

Gazzarri’s, run by self-styled ‘Godfather Of Rock’N’Roll’ Bill Gazzarri, was Van Halen’s old stomping ground, but it had a bad sound system and put on more obscure bands. The Troubadour was the redheaded step-child of the Strip, and didn’t mean much on a band’s resumé. Still, hard rock bands faced an uphill struggle.

“I saw the Ramones and I went, ‘Uh oh. This smells bad,” recalls Peter Margolis, guitarist for The Source. “I just thought this is what’s coming to replace glam and all the leftover early-70s power trios that were still trying to make it. Van Halen was really the only metal band out of all of us from that period to get signed. And it was really a fluke.”

Nearly 40 years on, the idea of Van Halen’s success being purely down to luck sounds ridiculous. But before Warners swooped in, they were drinking in the last chance saloon. They’d been turned down by every label they approached – their cause wasn’t helped by a dismal demo they’d made with Gene Simmons of Kiss, which provided no traction in getting them a deal.

“I think they were kind of running scared and wondering if it was really going to happen or not,” says Greg Leon, guitarist with Suite 19. “They’d been together five years, and all the record labels were passing on them.”

What they did have was a pair of secret weapons in the shape of Dave Lee Roth and Edward Van Halen. Most bands were lucky if they had one killer frontman. Van Halen had two.

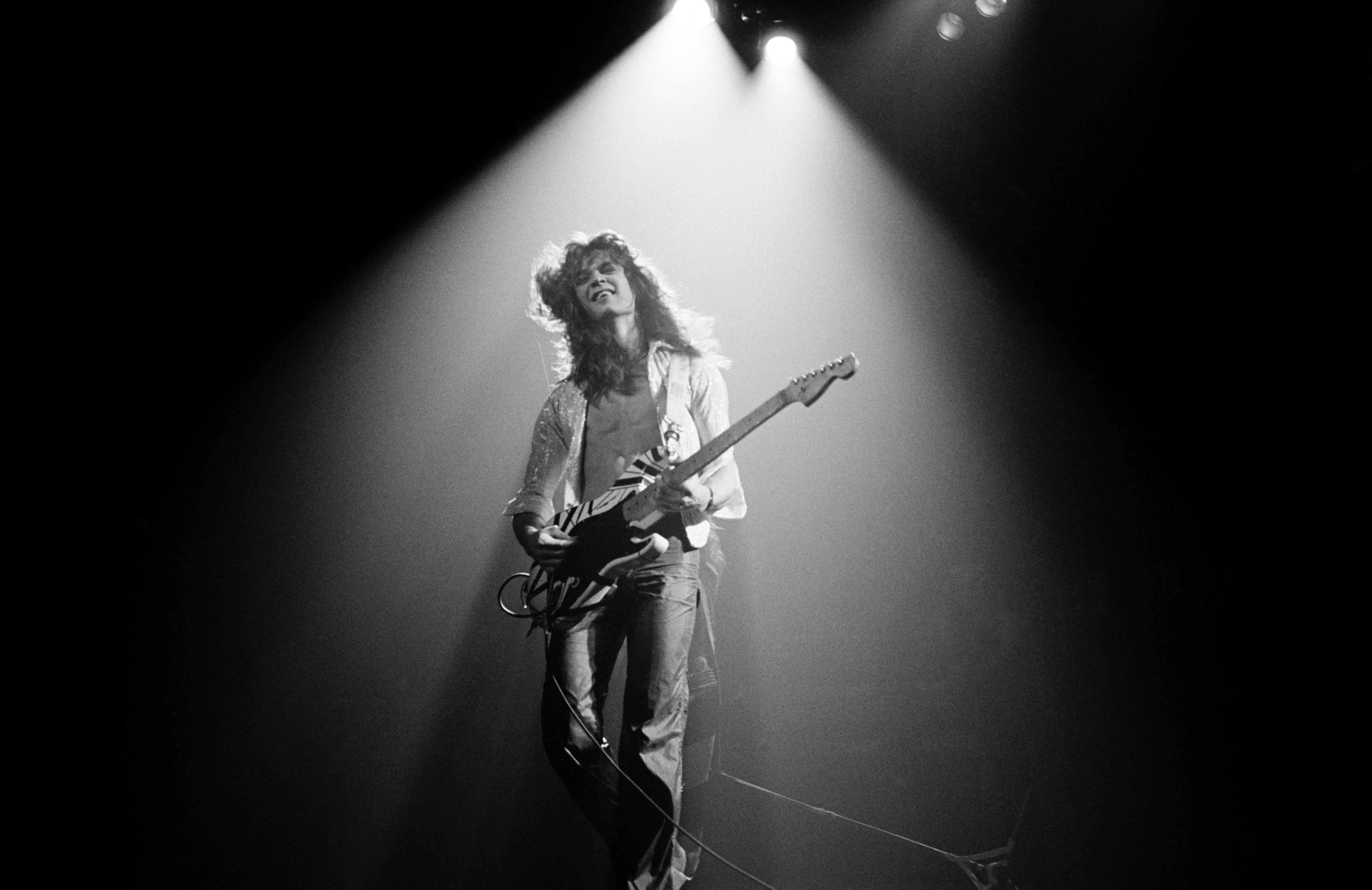

“I can tell you that the buzz they generated, which eventually landed them their record deal, was attributable solely and completely to the virtuoso guitar talents of Eddie Van Halen,” says Mike Kelley. “He inspired awe and excitement in everyone who saw him. Superstar was written all over Eddie.”

Everything finally changed for Van Halen on that June night, when Mo Ostin and Ted Templeman stepped out of the rain and into the Starwood. The band had no idea in advance that they were being scrutinised by two men who held their future in their hands – which was probably for the best.

“Ted Templeman and Mo Ostin came down to the Starwood, which was always kind of a bad place for us,” Edward Van Halen later told me. “It really tripped me out because when we were playing and Mo and Ted walked in, we really didn’t know. Somebody just said, ‘There’s somebody real important out there, so play good.’ It was some rainy Monday night without any people at all and still they came backstage and they loved it. They said, ‘If you don’t negotiate with anyone else, you’ve got what you want right here.’ We tripped out.”

For all the buzz surrounding them, Van Halen hadn’t even started playing their own songs until earlier in 1977 and they’d moved up the ladder of LA clubs from Gazzarri’s to off-nights and the Starwood and, ultimately, the Whiskey. But that was when the fire really started burning.

“What Mo and Ted heard was that Van Halen didn’t sound like anybody else,” says Peter Margolis. “All these other bands – Smile, A La Carte, Snow, Eulogy – were derivative of something. Eddie didn’t sound or play like anybody else. The other thing everybody forgets was that Eddie Van Halen was really a fucking good-looking guy and so was David Lee Roth. Like it or not, they got signed on their talent, on their original material, but also on their looks. They looked like Robert Plant and Jimmy Page. They had that thing that these other bands didn’t have.”

The band signed contracts the day after the Starwood gig. Warners had always been Edward’s first choice of label, as it was home to Deep Purple and Black Sabbath, two of his favourite bands. On top of that, Templeman had agreed to produce their debut album (he had previously worked with Montrose and Little Feat, among others).

It would be several months before Van Halen could start work on the record, as they waited for Templeman to finish work on the Doobie Brothers’ Livin On The Fault Line. They finally entered Sunset Sound Recorders in Hollywood in August 1977, where they spent just 21 days cutting the album – an astonishingly short amount of time for such a landmark record.

Templeman and engineer Donn Landee’s contribution to Van Halen can’t be overstated. The pair had been working together for years and had developed an intuitive sense about how to magnify the essence of what a band was. For Van Halen, that meant playing together in a room – and overdubs be damned.

Templeman realised that in order to capture the bombast and beauty of the band’s live performance, he would need to keep things simple and organic. With that in mind, he cut virtually every track live, without overdubs (the exceptions were Runnin’ With The Devil and Jamie’s Cryin’). This approach was exactly what Edward Van Halen was hoping for.

“What Ted managed to do was put our live sound on a record,” the guitarist told me. “Sunset Sound was just a big room like our basement actually [the band typically rehearsed in a subterranean room at Roth’s house] and we played at stage volume. The guys who ran the studio and maintained the place would walk in after we were done, boy, and there were beer cans all over the floor and hotdog smears all over the place. Van Halen is three instruments and voices with very few overdubs. I hate overdubbing because it’s just not the same as playing with the guys. There’s no feeling there to work off of.”

The music, clearly, was already there, but it was also the over-riding energy and party spirit of the album that proved addictive. Roth might not have had the most technically perfect voice in the world, but whether you liked his singing or not, it crackled with personality. Ultimately, what lifted the album was Edward Van Halen himself – the guitarist redefined the very vocabulary of what a rock guitarist could do.

“It was a turning point for me when I heard that record,” admits producer Mike Fraser, a veteran who has worked with everyone from Aerosmith to AC/DC. “It was hard rock done in a pop manner maybe for the first time with heavy guitars and slap reverb on them. It was a real head-turner. All the songs were there and with the production they managed to create a new sound. It was flawless.”

Nowhere was this new sound better illustrated than on the band’s take of The Kinks’ classic You Really Got Me. A song they’d been covering for years in the clubs, it took on new dimensions in the studio. The guitar tones were both monstrous and majestic at the same time. Rolling out his vintage Marshalls and plugging in his hot-rodded Stratocaster, Edward provided an early glimpse of what he would call his “brown sound”.

“The night Ted saw us play, we played that song and he got off on it,” Edward told me. “He’s going, ‘Hey, man, that might be a good song to put on the record.’ I thought, ‘Yeah, because we’ve all been waiting to do that song anyways since we were four years old.’ I mean, it sounds different than the original – it’s kind of updated. It’s been Van Halenized like a jet plane.”

If there was one track that instantly placed the guitarist in the pantheon of greats it was Eruption, his spontaneous, two-handed tapping instrumental masterpiece. It showcased a technique that would initially mystify and ultimately mesmerise every guitar player who heard it. Was that a synthesiser? Overdubbed guitar part? I asked Edward: what the hell he was playing on Eruption? He picked up my ’66 Strat and demonstrated how he did it. Even he had difficulty describing the technique.

“I really don’t know how to explain that,” he told me. “I was sitting in my room at home, drinking a beer, and I remembered seeing people stretching one note and hitting the note once. Nobody was really doing more than just one stretch and one note real quick. So I started dickin’ around and said, ‘Fuck! This is another technique that nobody really does.’”

Eventually, people would untangle the knot that was this revolutionary new approach, and aspiring guitar players everywhere would add it their arsenals. But when Van Halen’s self-titled debut album was released in February 1978, it was still a perplexing and mysterious technique.

Ironically, Van Halen was a slow starter – it peaked at No.117 on Billboard’s Top 200 album chart. But its impact couldn’t be measured in sales figures. Instead, it became the standard by which subsequent hard-rock albums would be measured. It was both touchstone and template for more than one generation of bands that followed, every bit as revolutionary as Are You Experienced?, Led Zeppelin’s debut or the Jeff Beck Group’s Truth album. Today, its sales stand at more than 10 million – second only to Van Halen’s huge crossover album 1984.

Van Halen may have taken the very first step on a journey that would eventually lead to superstardom, but in 1978 there was still work to do. With their debut completed, the band hit the road on a press junket that included record-store appearances, meet-and-greets with fans, radio station interviews and a lot of handshaking.

Though Ted Templeman and Mo Ostin were champions of the band, they never really believed Van Halen would turn into a huge, out-of-the-box success the way Boston or Foreigner had. The myth of Van Halen as fully formed rock gods hoovering up the platinum discs right from the start has been exaggerated over time. They weren’t even necessarily being touted at the time as the Next Big Thing.

The fact is, Van Halen got where they did through a combination of ambition, focus and sheer hard work. They’d slogged through six sets a night at Gazzarri’s fuelled by the belief that they would someday make it. Even after the album was recorded, they remained fixtures on the Strip through to the end of 1977 – they still needed a paycheck, after all. But for anyone who saw them, their force of will was hard to ignore.

“When Van Halen was rolling in it was like, ‘It’s all a party but it’s really fucking serious,’” says Brian Tanneville. “They meant business and they knew they were gonna be great. Dave was a shameless self-promoter and as arrogant as the day is long, but he really did have the greatness.”

Roth established his persona early on. He was already Diamond Dave – loud, funny and ready to joust with any journalist up for a war of words. Edward, by contrast, was more passionate about the band than any of them, but he was also a little unsure about his own abilities.

That uncertainty seems remarkable in light of his inventiveness and the band’s success, but when he sat on my couch, playing my guitar and admitting that he hoped the album would do “okay”, I believed him. Then there were Edward’s elder brother, Alex, and bassist Michael Anthony. The former was a little edgy; the latter was simply a jovial, good-natured cat.

All four knew that the time had come to shake up rock’n’roll, and make it clear to the old guard that there was a generation of new bands after their crown. This they did with a sledgehammer in one hand and stick of dynamite in the other.

“It’s not so much you take the place of anybody but this whole music business turns around,” said Roth at the time. “It’s ‘what’s happening now?’ By the time you answer, it’s too late and something else is happening. Whereas you have a Deep Purple on one side and a Bob Marley on the other, it’s very easy to squeeze in a Van Halen, Blondie, The Knack, Aerosmith or whatever it is. There’s always room for something new. I say bring ’em all on and new blood all the time every day. There’s always wolves at my door, man. I’m always on my toes.”

The band were relentless in steamrolling anything put in front of them. Soon after the debut album’s release, they opened for Journey and Montrose. The two better-known bands must have wondered what they’d taken on.

“When we started out with Journey and Montrose, we were brand new,” Eddie told me. “I think our album was only out a week at the start of the tour and then we were almost passing up Journey on the charts and stuff. So they’re freaking out. I think they might be happy to get rid of us. We’re very energetic and we get up there and blaze on the people for half-an-hour. That’s all we’re allowed to play with them. We don’t get soundchecks. We don’t get shit, but we’re still blazing on the people, man.”

Even more memorable was their stint opening for Black Sabbath on the latter’s tour in support of their Never Say Die! album. The Birmingham band’s original, Ozzy-led incarnation was on its last legs, brought down by a combination of long-term exhaustion, creative bankruptcy and destructive drug abuse. The Americans blew the more established band offstage every night.

“We were like the young roosters out there, going for it,” bassist Michael Anthony later recalled. “At that point, we knew we’d be headlining after that ’cos we were blowing Sabbath off every night.”

The Sabbath tour was the culmination of everything Van Halen had been working towards. The guard had been changed, the new kings had been crowned.

Close to 40 years on, Van Halen’s debut album has lost none of its shine, nor any of its importance. Before it, hard rock was in serious danger of becoming staid and lifeless. Afterwards, every self-respecting rock band cited it as a touchstone. It’s not just one of the great debut albums, it’s one of the great albums full-stop. You can hear its incomparable sound and bravura attitude echoing through the 1980s and beyond, its success revitalising not just the Sunset Strip, but similar scenes all around the world.

When I spoke with Edward that first time and told him how amazing I thought the album was, he almost seemed embarrassed by the praise.

“I think it’s good,” he said, the assessment offered up with equal doses enthusiasm and ‘aw shucks’ humility. “I hope it does okay. All we’re trying to do is put some excitement back into rock’n’ roll. It seems like a lot of people are old enough to be our daddies and they sound like it or they act like it. They seem energy-less. It seems like they forget what rock’n’ roll is all about.”