Voivod drummer Michel ‘Away’ Langevin remembers the first night his band opened for Rush. It was March 20, 1990, in Edmonton, Alberta, and the iconic Canadian trio were touring their home country in support of Presto, a record that found them gently rowing back from the synth-heavy furrow they’d been pursuing during the previous decade.

By contrast, Voivod were heading in the opposite direction, relatively speaking. The Quebec quartet had begun life as a primitive thrash metal band, all white hi-top sneakers and flailing hair. But their recent albums had seen them introducing more complex musical and lyrical themes into their music. Their latest, the previous year’s prog metal landmark Nothingface, had even included a cover of Pink Floyd’s space cadet anthem Astronomy Domine – something that would have been unthinkable for their 80s thrash contemporaries Metallica or Slayer to do.

As Away and his bandmates walked backstage that first night, they found a bottle of champagne waiting for them. Accompanying it was a note signed by Rush’s Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart wishing them luck.

“That was a huge moment for us,” says Away now. “Rush were so influential. The fact that the drummer wrote the lyrics and the concepts was big for me. And Alex Lifeson was one of [Voivod’s then-six-stringer] Piggy’s favourite guitarists.”

But there was much more significance to that bottle of bubbly than just the best wishes of one of prog rock’s great bands. Consciously or not, it was a baton being handed down from one generation to the next – an acknowledgement that the future, or one strand of it, belonged to Voivod and their ilk.

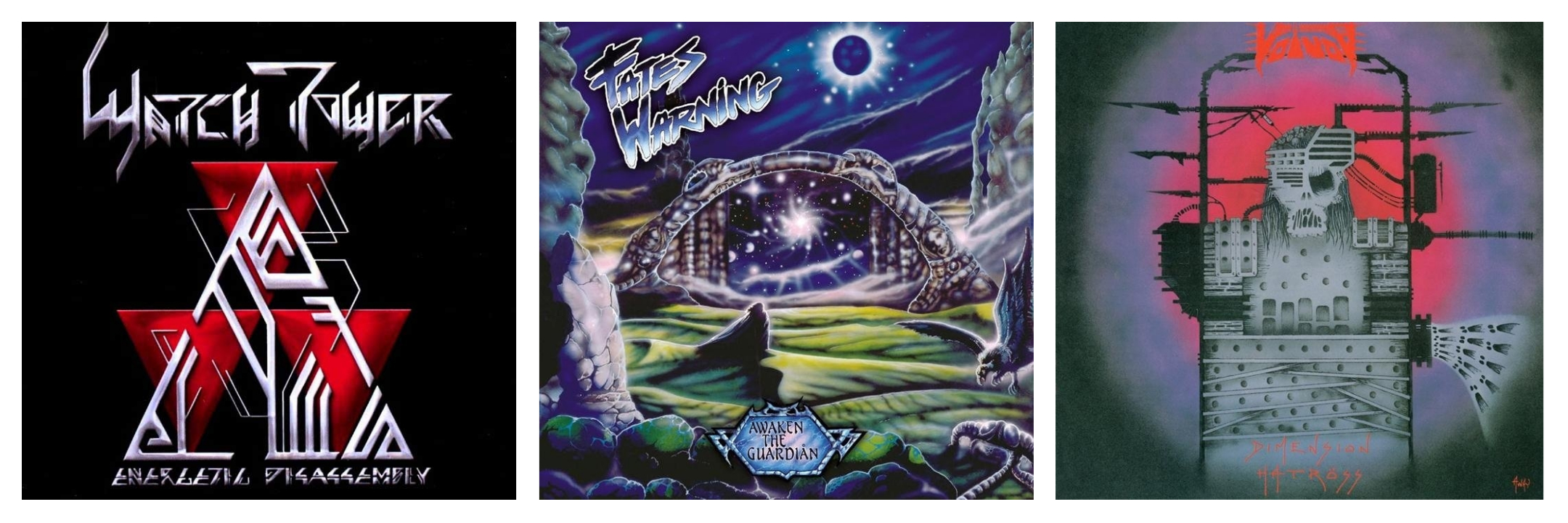

Voivod’s support slot with Rush was one of the key stepping stones in the upward trajectory of prog metal, a genre that had risen from nothing in a handful of unconnected hotspots across North America less than a decade before to become an emerging musical force. There was Watchtower from Texas and Fates Warning from Connecticut, Queensrÿche from Seattle and Crimson Glory from Florida. And there was a band named Majesty from Boston, who had recently changed their name to Dream Theater and would eventually go on to be the most successful of them all.

Charlie Griffiths, guitarist with British prog metallers Haken, is a diehard fan of the early prog metal pioneers. “The music I hear in my head is definitely shaped by those early formative years listening to bands like Watchtower and Fates Warning,” he says. “They were totally ahead of their time.”

Contrary to received wisdom, prog wasn’t on the ropes in the 1980s – it was evolving. As Genesis, Yes, Rush and the other giants of the previous decade dressed themselves up in pop drag and reinvented themselves, a group of British diehards were marrying the old values to new ones under the banner of ‘neo-prog’.

But the most interesting grassroots developments were happening in the US, in the unlikely confines of the heavy metal scene. Talking to the prime movers of the nascent prog metal movement three and a half decades on, it becomes clear that it was as much a product of coincidence as it was forward-thinking.

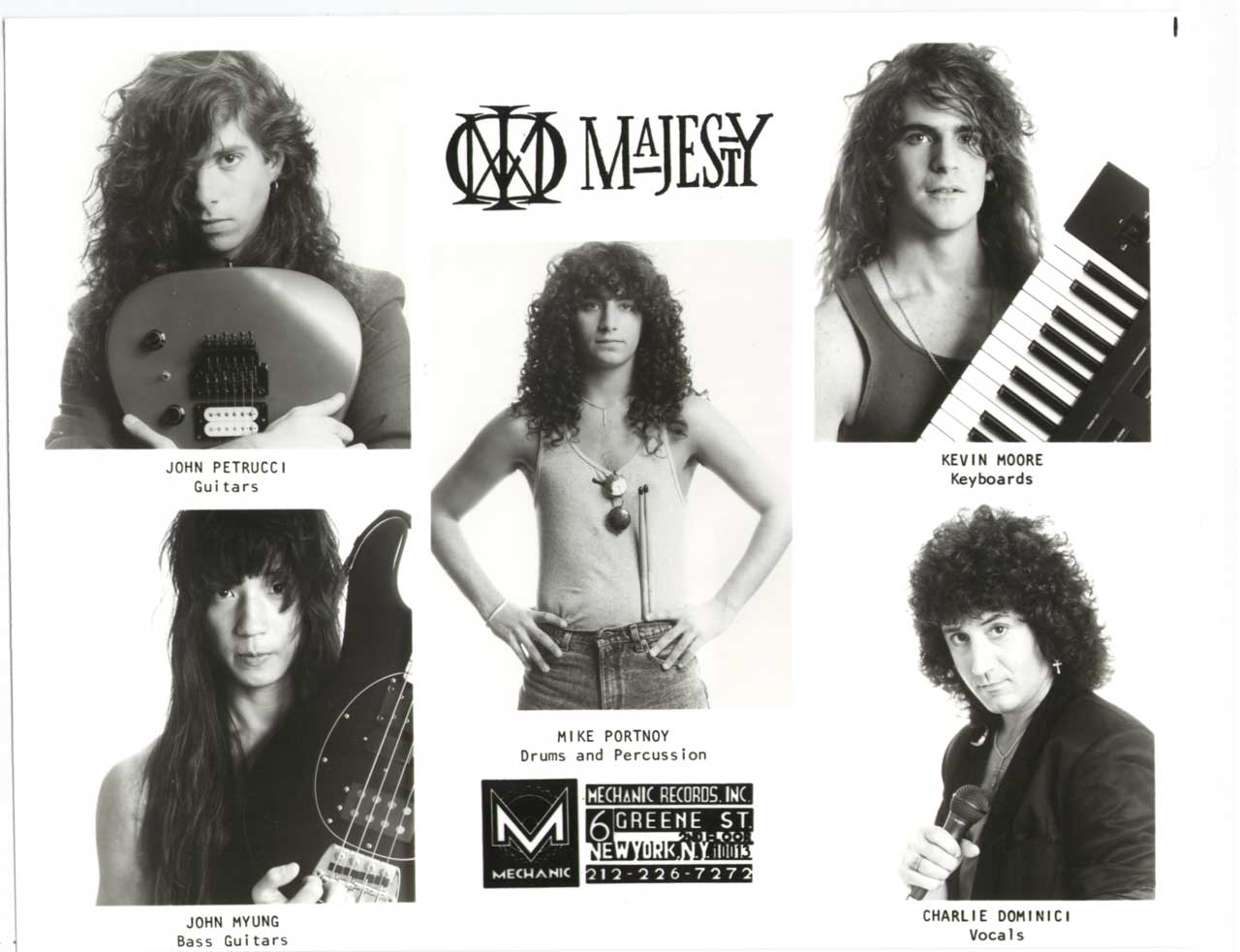

“We were just filling a void,” says former Dream Theater drummer Mike Portnoy. “We wanted to take the music as far as it would go, take the instruments as far as they would go, take the composition to extremes. If we thought there was a gap, we knew there had to be an audience for it.”

The idea of progressive rock and heavy metal coming together wasn’t new. Rush and Yes played to as many long-haired, denim-clad rockers as they did professorial prog fans, while young bands such as Iron Maiden were prog connoisseurs underneath the denim and leather, their record collections filled with Jethro Tull and Gentle Giant albums alongside Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin.

But by the early 80s, metal was accelerating, literally and philosophically. Proponents and fans alike were more interested in speed, heaviness and outrageousness than they were musical complexity. In the US, 1982 saw the birth of the thrash metal movement, in which everything was sacrificed on the altar of velocity.

“It wasn’t like you had to keep quiet about your love of progressive rock,” says Jim Matheos, guitarist and linchpin with prog metal pioneers Fates Warning. “We were totally open about it. But there was definitely a slump in interest in prog at that time among rock musicians. People were more into the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal.”

Matheos founded Fates Warning in Hartford, Connecticut with original vocalist John Arch in 1982. They took their influences from both sides of the musical coin: in their heads, Black Sabbath, Deep Purple and Danish occultists Mercyful Fate happily co-existed with prime Genesis, Jethro Tull and Yes.

Fates Warning’s first album, 1984’s Night On Bröcken, was standard issue 80s heavy metal, distinguished only by John Arch’s helium-pitch vocals – a characteristic shared by many of the prog metal bands who followed.

“The first record stands alone – there’s a lot of the Maiden influences there,” says Matheos. “But after that we became more confident as musicians, we became better writers. We wanted to expand our sound a little bit. We wanted to challenge ourselves as musicians and as listeners.”

By their second and third albums, 1985’s The Spectre Within and the following year’s Awaken The Guardian, Fates Warning were beginning to shake off their rudimentary musical approach. The songs were becoming bolder and more complex, wearing their progressive influences on their denim jacket sleeves. It was the sound of a band liberating themselves.

“I don’t think we felt like we were being held back by anything,” says Matheos. “It was the whole experience of exploring new things, especially when you’re that age.”

The period between 1982 and 1985 represented the first stirrings of what would go on to become progressive metal. “We were aware of something because we subscribed to all the magazines,” says Matheos. “But at the same time, coming from where we did in the backwoods of Connecticut, we were isolated from the whole thing too. That drove what we were doing. We didn’t want to get folded in with the rest of them.”

Nearly 2,000 miles away in Austin, Texas, another group of like‑minded musicians were thinking exactly the same thing. Watchtower had been put together by Rick Colaluca, bassist Doug Keyser, guitarist Billy White and singer Jason McMaster in 1982 – coincidentally the same year as Fates Warning.

The two bands didn’t became aware of each other until much later, but there are vivid parallels to their stories. Like their north-eastern counterparts, the members of Watchtower grew up listening to contemporary rock and metal outfits like KISS, Aerosmith, Iron Maiden and the emerging NWOBHM bands before gravitating to the more challenging end of the prog spectrum: King Crimson, Van der Graaf Generator, Frank Zappa.

“When we started, it wasn’t really a conscious decision to do what we ended up doing,” says Rick Colaluca. “It wasn’t like, ‘Okay, we’re going to do all this technical math stuff.’ It was more, ‘We love this heavy, fast stuff and we love this other, more complicated stuff – let’s do something different and incorporate both parts.’”

Like Fates Warning, Watchtower started out as a route-one heavy metal band but rapidly became something else. Between 1982 and the release of their debut album, 1985’s remarkable Energetic Disassembly, they didn’t so much jettison their heavy metal beginnings as warp them out of recognition. Marrying the velocity and violence of the newly birthed thrash metal scene to the complexity of prog and jazz rock, they forged an unlikely missing link between Metallica and Mahavishnu Orchestra. Even more than Fates Warning, Watchtower were a band ahead of their time.

“Once we latched on to the concept of what we wanted to do with our music, we were just driven to do it,” says Colaluca. “It wasn’t about competing with anyone or trying to outdo anyone. It was just about doing the same thing we all seemed to be of the same mindset about, and we pressed forward with it.”

Austin had long garnered a reputation as a hothouse for mavericks, and Watchtower’s horizon-expanding approach was embraced by the city’s rock community. It helped that their shows were visual spectacles, more in tune with the frantic energy release of thrash metal than prog’s studied musicianship.

“For some people, progressive rock is boring and kind of stuffy live: ‘Okay, we’re going to be this perfect thing,’” says Colaluca. “We decided to lay it all on the line and go crazy. If we made mistakes here or there, fine. When we were hitting on all cylinders, it was a fucking thing of beauty. It wasn’t just out there playing a record. It was like, ‘Holy fuck, that was fucking awesome.’”

Having built up a loyal following in Austin, Watchtower began to venture further afield, testing the water for their new prog metal hybrid.

“Most of the other bands we played with were straightforward metal bands and there were some people who just didn’t get it,” says Colaluca. “It felt like we were definitely out there on our own.”

Half a continent away, Fates Warning were going about things in a different way. They found it harder to play gigs – partly because of their geographical location, tucked away in the north‑eastern corner of the US, but partly because, unlike their southern counterparts, no one knew quite what to make of them.

“We didn’t really do a proper tour until 1988,” says Matheos. “Before that, we would play local gigs, go to New York, maybe play as far out as Cleveland, but we were really doing 10, 12, 15 gigs a year for the first three or four years of this band’s existence. When we did tour, we’d get paired up with some odd groups – Motörhead or Anthrax. People were a little bit baffled by us.”

Instead, they existed on the record sales that came on the back of the buzz built via appearances in heavy metal magazines such as Kerrang!. But the prog community, such as it was, seemed largely oblivious to their existence.

“There wasn’t really any great collective of people demanding a sound that mixed progressive rock and heavy metal,” says Matheos. “So we weren’t consciously aiming ourselves at them. We weren’t aiming ourselves at anyone.”

One person who was paying attention was a teenage New Yorker named Mike Portnoy, a precociously talented drummer and rapacious devourer of new music. Portnoy had put together his own band, Majesty, at the Berklee College Of Music with guitarist John Petrucci and bassist John Myung. They shared a vision of uniting the prog music they’d been weaned on in the 70s with metal’s contemporary new styles.

“At that time the pure prog scene was pretty much non‑existent,” says Portnoy today. “I was missing those kinds of bands, but I was also a full-on metalhead into Slayer and Exodus and all that stuff. When I met the other guys, we all wanted to combine the two things, like a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup.”

Portnoy was heavily involved in the thrash metal tape-trading scene – a pre-internet network of fans swapping new music via the post. “I knew of Fates Warning and Watchtower and Crimson Glory and all those kinds of bands because of tape trading,” says Portnoy today. “I remember Watchtower’s first American tour – a couple of the guys stayed at my house. They were like Rush on steroids. I went to see Fates Warning whenever they came to New York.”

As Majesty’s de facto manager, he was the one who would send out their own tapes to promoters, labels and other bands. One of these, the semi-legendary Majesty Demos, came into the hands of Jim Matheos.

“Oh, I totally heard the potential,” says Matheos. “I knew something was going to happen. I listened to their tape over and over again. I was amazed at what they were doing. And I was a huge fan of Voivod, who were already putting out albums. Especially the guitar playing.”

Like Fates Warning and Watchtower, Voivod came from a metal background, but the Canadians’ transition was an even bigger jump. Their debut album, 1984’s War And Pain, was a brutal, punk-influenced assault, and the follow-up, Rrröööaaarrr, was only marginally more refined. By the time of 1987’s Killing Technology, though, they were beginning to incorporate more complex musical explorations in their thrashy sound, while a central concept themed around an intergalactic warlord would provide an overarching narrative not just for the album but for their entire career.

It was no coincidence that Voivod had toured the US with Swiss avant-gardists Celtic Frost a year earlier, and the opening band in Austin was Watchtower.

“They were one of the first thrash bands I’d seen playing prog rock,” says Away, who grew up listening to VdGG and King Crimson.

It was an approach that Voivod themselves began to take onboard, inspired partly by their own developing musical skills.

“Between 1983 and 1988 we rehearsed every single night,” Away says. “We were ready to add a little bit more of the prog rock thing into our music. When we toured in 1987, we noticed the metal audiences were a little puzzled by our style.”

Voivod’s new approach reached fruition on 1988’s Dimension Hatröss, a fully fledged prog metal concept album. Jettisoning the 100mph thrashings of old, its complex musicality, shifting rhythms and science fiction leaning positioned the Canadians as the Van der Graaf Generator of metal. Its follow-up, 1989’s Nothingface, was even more assured, ramping up the prog aspects and throwing in a cover of Astronomy Domine, just in case anyone hadn’t got the message.

“1989 and 1990 were great for us,” says Away. “The video for Astronomy Domine had a lot of airplay on MTV, we got offered big tours with bands like Rush and the album sold quite a lot. To us, it felt like justification that what we were doing musically was right.”

In New York, Mike Portnoy wasn’t having as much luck. His band had changed their name from Majesty to Dream Theater and signed a deal with major label offshoot Mechanic Records, who released their debut album, 1989’s When Dream And Day Unite. That record – featuring singer Charlie Dominici – was a fine calling card, tempering its intricate metal riffing with swathes of keyboards.

The band had, not unfairly, been marketed as “Metallica meets Rush” – only the masses weren’t quite ready for that combination yet, and the record sank without trace.

“We never went on tour, never made a music video, which was absolutely crucial back then,” says Portnoy. “We were watching Voivod and Queensrÿche doing really well and going, ‘Wait a minute, we’re different but not that different.’ We started to get discouraged.”

Rather than quitting, the band doubled down on their initial gameplan. They fired Dominici and spent the next two years working on the music for what would become their breakthrough album, Images And Words.

“We were working day jobs every day, going to band practice every night, looking for a new singer, looking for a new record deal,” says Portnoy. “It was a very hard time. I’m shocked we made it through. But we persevered and we finally got the payoff with Images And Words.”

Released in 1992 and featuring new singer James LaBrie, Images And Words was more than just a lifeline for Dream Theater. The single Pull Me Under gave them a bona fide hit, dragging the album along in its wake.

“We were plastered all over radio and MTV with an eight-and-a-half-minute song,” says Portnoy. “That hadn’t happened since the days of Yes and ELP in the 70s.”

Dream Theater had finally blown the doors off, allowing prog metal to step through into the mainstream. The only problem was that many of their peers either weren’t ready or weren’t able to step through with them. Voivod had faltered with Angel Rat, the follow-up to Nothingface. A shifting line-up and lack of laser-sharp ambition meant that Fates Warning had never made the leap from culthood to mainstream acceptance. And Watchtower – the band who brought together prog and metal like no one else – had simply fallen apart after their astonishing second album, 1989’s Control And Resistance.

“We took four years between albums, which didn’t help us,” says Watchtower’s Colaluca. “But we had line-up problems and we just hit a barrier so we decided to shut the whole thing down. We did continue writing piecemeal after that, but real life got in the way.”

“Watchtower are the band from that scene that should have made it,” says Portnoy. “They were the most extreme ones from that genre. And Fates Warning too – as well as they did, they should have had the success Dream Theater had, especially with the Parallels album, which came out about a year before Images And Words.”

“Maybe there were missed opportunities back then,” says Fates Warning’s Matheos. “I don’t know why the guys from Dream Theater became superstars and we didn’t. But they were an amazing band, and they worked hard and deserved it.”

Dream Theater and Queensrÿche – whose 1988 album Operation: Mindcrime remains a landmark of the genre – may have been the only two bands to have emerged from prog metal’s primordial soup who went on to genuine success, but the legacy of those early innovators resonates down the years. It’s there in everyone from Meshuggah – who have taken Watchtower’s prog thrash to sometimes unfeasible new levels of extremity and complexity – to new-school heroes such as Leprous, Between The Buried And Me and Haken.

“When I think about how they recorded all those parts without all the computer and studio tools we have today, it blows my mind,” says Haken’s Charlie Griffiths. “When Haken played Prog Power USA last year, Fates Warning played the Awaken The Guardian album with the original line-up, so it was a real ‘full circle’ kind of feeling.”

Today, Dream Theater remain the flag‑bearers for the original prog metal scene, though they don’t stand alone. Despite having gone through many ups and downs, Voivod have continued to innovate and the Canadians are set to release a new album this year. Fates Warning still put out albums and play live on a semi‑regular basis, while Watchtower reunited and have released a slow but steady drip of songs this decade, culminating in 2016’s Concepts Of Math EP.

“I don’t want to say Dream Theater created a new market, because bands like Fates Warning, Watchtower and Voivod were all doing it before us,” reflects Mike Portnoy. “But I think collectively we all definitely created something that did change music and kept prog’s spirit alive in a radically different form.”

Originally published in Prog 89